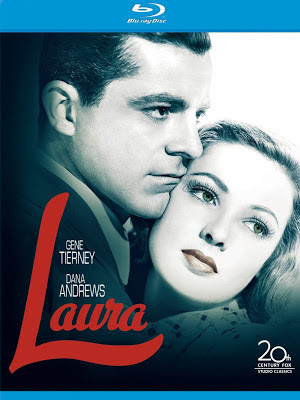

LAURA: Blu-ray (2oth Century-Fox 1944) Fox Home Video

Scratch the

surface of Otto Preminger’s Laura

(1944) and you will discover one of the most fascinating and demented character

studies ever put on film. Owing to Joseph LaShelle’s moody cinematography Laura is oft’ classified as a film noir. Superficially, it has that appeal. But Laura is much more, and, in truth,

does not adhere to the most time honored of noir’s precepts. No, from its

curiously homoerotic opener between a middle-aged dandified fussbudget and

ultra-butch New York City police detective, to its revelation that the supposed

murder victim is actually somebody else, Laura

careens through its lascivious labyrinth of high society gadabouts, shifting

gears and switching genres mid-way to reveal a devious and complex social study

far more captivating than its traditional crime story.

Our heroine,

Laura Hunt (Gene Tierney) is not the femme fatale, nor is there another

skulking about this moneyed backdrop to unravel her perfect world. Our hero, Det.

Lt. Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews) inexplicably develops a necrophilia-esque

obsession with the deceased from a portrait hanging in her apartment. Laura’s

closest friend, newspaper columnist and radio commentator Waldo Lydecker

(Clifton Webb) is an imperious coxcomb, more consumed with his Svengali

ambition to take this lowly stenographer and mold her into a lady of culture

and breeding, while Laura’s fiancée, oily gigolo Shelby Carpenter (Vincent

Price) is a manipulative sponge, even as he procures other sexual relationships

along the way – including one with Laura’s aunt, Ann Treadwell (Judith

Anderson).

Yes, Laura is an elegant film. But it defies

its stylized glamour with a misleadingly pockmarked decadence; relishing the

wicked betrayals and venomous duplicities that ultimately lead to murder. Based

on Vera Caspary’s novel, ‘Ring Twice for Laura’, Jay Dratler

and Samuel Hoffenstein’s screenplay retains Caspary’s air of the foreboding

almost from the moment David Raksin’s lush monothematic score fades and we hear

Waldo Lydecker’s solemn voice over declare “I

shall never forget the night Laura died.”

We are

introduced to butch NYPD det. Mark McPherson, coolly admiring the odd menagerie

of art and crystal adorning the great room inside Waldo Lydecker’s penthouse apartment.

At the behest of a disembodied voice calling to him from the next room McPherson

opens the door and enters an even more disturbingly lavish Roman bath with

Waldo, nude and soaking in his tub; a typewriter at his side. The sexual

tension in their initial ‘cute meet’ is hardly subliminal. McPherson’s laconic

grin as he observes the rather bony Lydecker emerging from his bath, tossing

him his fuzzy robe and following his exit into an adjoining boudoir do more

than suggest naughty – if slightly condescending - thoughts. And McPherson ups

the ante by allowing Lydecker to shadow him to his various ports of call in the

Laura Hunt murder investigation.

Their first

stop is Ann Treadwell’s apartment. Ann is cordial at the outset. But when

McPherson’s questions begins to infer a sexual relationship between Ann and

Laura’s fiancée Shelby Carpenter – thus providing amusement for Lydecker as

well as fodder for his column – Ann’s social graces lapse. Shelby appears on

cue, unassuming and very willing to help in any way that he can. But even he

isn’t particularly heartbroken over Laura’s death. McPherson escorts the two

men to Laura’s apartment with Shelby promising to locate an extra key Laura

always kept in the apartment. Unaware that the police have already taken a

meticulous inventory, Shelby plants his key - in his possession all along - and

McPherson wastes no time in calling him out.

Later, Lydecker

and McPherson retire to a light lunch inside Laura’s favorite restaurant and

through a flashback and Lydecker’s voice over we regress to the elegant Miss

Hunt’s first encounter with the austere Waldo inside the Algonquin Hotel’s

dining room. He glibly admonishes her for attempting to gain his endorsement on

a fountain pen, but shortly thereafter arrives at Bullit & Co., the ad

agency she works for, to reconcile their differences and agree to the endorsement.

Since the flashback is told entirely from Lydecker’s perspective we have

absolutely no way of knowing whether or not it is the truth. Yet, it seems

unlikely that the ambitious Laura would allow herself to be so easily

manipulated by Lydecker’s ascorbic wit – even if his endorsement of the pen is

basically responsible for launching her career.

McPherson

decides to drive out to Laura’s cottage in a perilous thunderstorm. But once

there, he again encounters Shelby attempting to cover up what he perceives is a

clue; the whereabouts of a rifle that might be the weapon used to shoot Laura

Hunt in the face. Curiously, McPherson does not arrest Shelby, but instead

allows him his freedom, returning alone and even more perplexed to Laura’s

Manhattan brownstone. Lydecker accuses McPherson of compromising the case by

having fallen in love with a corpse. But McPherson admonishes Lydecker for his

liberties, and thereafter decides to spend the night in the apartment to come

to terms with his own feelings about the case. McPherson is startled in the

dead of night by the arrival of none other than Laura Hunt who is equally

perplexed at finding a stranger inside her home.

After his

initial shock and surprise McPherson learns from Laura that she had gone to a

mountain retreat for the weekend – removed from telephones and newspapers and

therefore has been entirely unaware of the maelstrom of inquiry surrounding her

murder investigation. McPherson also pieces together a scenario: that one of

the advertising firm’s models, Diane Redfern was mistakenly shot in the face

for Laura. It seems Diane had been using the apartment at Shelby’s invitation. Determined

to spring a trap on those closest to Laura, McPherson re-introduces her friends

to the resurrected – each suffering their own inimitable startle as a result.

Laura’s devoted maid, Bessie Clary (Dorothy Adams) has a frantic breakdown

while Waldo faints dead away at his first sight of her.

McPherson does

some slick detecting to test the guilt of those closest to Laura, then suggests

that it was Laura who killed Diane Redfern because of her jealousy over Diane

and Shelby’s tryst; a revelation Laura vehemently denies. Back at the police

station McPherson becomes convinced of Laura’s innocence. Returning Laura to

her apartment McPherson exposes his true feelings to her and she willingly

reciprocates. McPherson then tells her to forget all about the case, vowing to

bring the killer to justice. In the

meantime, Lydecker has evaded the police guard standing outside Laura’s

apartment building and sneaks inside through the back way using his own key,

determined to finish off the woman he seemingly cannot live without, yet will

not allow anyone else to possess.

Lydecker

confronts Laura at the point of a shotgun he has been concealing inside a

secret panel in her clock ever since the night of the first murder. But at the last possible moment McPherson and

his fellow officers burst into the room. Lydecker fires off a round, missing

the police but destroying the clock he once gave Laura as a gift – an exact

replica of the timepiece in his apartment. The police open fire and kill

Lydecker; his bittersweet words of farewell whispered to her as he expires. It

is interesting to note that Otto Preminger does not conclude the film with

McPherson’s gallant rescue and passionate embrace of the emotionally terrorized

Laura, but instead pans to a close up of the clock; its time piece destroyed,

its inner workings revealed, just as Lydecker’s insidious deceit and jealousy

have also been exposed by his twice failed assault on Laura.

Nominated for

5 Academy Awards and winning one for its cinematography, Laura is a sublime who done it. Yet, like the narrative

complexities revolving around the discovery of who murdered chauffeur Sean

Regan in John Huston’s The Big Sleep

(1946) the ‘who’ in Laura is of far

less importance or even significance than the ‘why’. Waldo Lydecker: the sophisticate – powerful,

popular, successful cultural mandarin of his time, disseminating acidic charm

and razor-backed wit to millions of sycophantically adoring fans while hobnobbing

among the hoi poloi. Waldo; so obvious in his sexual predilection toward men

rather than women and more likely become jealous of McPherson’s steely-edged,

rough and tumble masculinity. Why should this man wish to destroy two lives

(Laura’s and his own) with her murder? True enough, Waldo regards Laura Hunt as

his personal property – a stylish consort he helped sculpt for a king from the

raw materials of an inexperienced ingénue: not for a cop or even a gigolo. Yet,

surely the platonic nature in their relationship thus far has not escaped him. Not

Waldo Lydecker – a man of sphinxlike infallibility.

What of our

hero, the square-jawed and equally square-shouldered hunk du jour, Mark

McPherson; slowly devolving in his unflappable powers of deduction from an

inexplicable affectation for the presumed dead woman he has never met? McPherson,

the stolid good cop who experiences ephemeral glimpses of utter elation only

twice in the film: once when he learns from Laura that she has decided not to

marry Shelby Carpenter, then again after his interrogation of her leads to the unequivocal

conclusion that Laura Hunt could not have murdered Diane Redfern. McPherson is

investigating a murder, not the woman who has miraculously come back from the

grave. Yet, she has possessed him from the beginning, even taken over where otherwise

cool logic ought to have prevailed.

And then there

is Ann Treadwell – the devilishly clever socialite, perfectly satisfied to

remain the object of sexual and financial exploitation until her niece takes a fleeting

romantic interest in the same destructive man – Shelby Carpenter. In one of

Laura’s most revealing sequences, Ann confronts her niece in the powder room;

unapologetically outlining the rather tawdry reasons why she, and not Laura,

must wind up with Carpenter in the end.

Finally, there

is the title character of Laura to consider – the outwardly glamorous, though

hardly fatal vixen: mere veneer for an otherwise forthright, if ambitious, though

completely honest and utterly hard-working lady of substance. In spite of

Lydecker’s promotion of the pen, Laura is self-possessed. She has seen through

both Carpenter and Lydecker’s façades. Moreover, she is her own woman; not to

be managed or manhandled or even worshipped by a lover, but respected and loved

for herself with whomever she ultimately choses for herself; an undeniably

progressive approach to the 1940s Hollywood heroine.

Otto Preminger’s

stroke of brilliance in Laura is that

he never takes sides with any of these characters. Traditional fare of this ilk

and vintage always clearly delineated the righteous from the evil. But

Preminger makes no judgment call on any of the goings on or peccadillos exposed

throughout this story. Instead, he charges the audience with enough

sophistication to read between the lines, to quietly observe and make their own

assessment of each character’s motives and reactions. And from a purely empathetic perspective, we

do just that. Consider this: that Waldo Lydecker – despite his flawed obsession

to control Laura Hunt – is never entirely despised for it; that Mark McPherson’s

personal involvement in the murder investigation never leads us to conclude he

has compromised his moral principles or even his police ethics for the sake of

his own carnal lust; that Ann Treadwell’s need to steal Shelby from her own

niece is predicated on conflicted ideals that strangely enough seem high-minded

and sincere – albeit, in a very insincere way. Preminger makes us aware that

each character is neither entirely pure of heart nor destructively evil. These characters are merely – and occasionally,

very tragically – flawed.

In the final

analysis, Laura is a seminal

masterwork of melodramatic magnificence whose influence in American movies can

be extrapolated in everything from Leave

Her To Heaven (1945) and Vertigo

(1958), right up to L.A. Confidential

(1997) and The Black Dahlia (2006).

It is a peerless film noir – if one chooses only to regard it as such – and an

extraordinary glimpse into the pitted willfulness of self-destructing lies,

treachery and deceit.

Fox Home Video

gives us a handsome Blu-ray indeed; dual layered with a solid bit rate and

remarkably clean transfer. Laura’s

original camera negative has long been lost and previous DVD incarnations were

very gritty, somewhat dark and riddled with age related artifacts. All of these

shortcomings have been corrected on the Blu-ray. In fact, it becomes apparent immediately

following the 20th Century-Fox logo that the print master in this

restoration is different. David Raksin’s emblematic Laura theme had always begun rather abruptly following the Fox

trademark, the result of several frames missing at the start of the main title.

Now, we get a very smooth fade up and transition – as it should be.

The gray scale

has been impeccably rendered: the B&W image considerably brighter than I

expected. Never having seen the film on

film I cannot say with any degree of certainty that this is how Laura looked back in 1944. But if

contrast has been artificially boosted, the results are not detrimental to the

overall presentation. In fact, Laura’s

visuals are clean, sharp and very solidly represented. There remains an

occasional blip of edge enhancement here and there – nothing terribly

distracting on the whole, but noticeable nonetheless. Overall, there will be no

complaints from the cheap seats. Laura

looks fabulous. The DTS mono audio has also been cleaned up to reveal very

delicate sonic textures in the original tracks. Raksin’s iconic underscoring

has never sounded more vibrant.

Extras have

all been teleported over from the DVD and include two distinct audio commentaries:

from Fox historian Jeanine Bassinger, the other from Raksin – who has

remarkable recall. We also get two

A&E Biography Specials (with their A&E Biography intros lopped off):

one on Gene Tierney, the other on Vincent Price. Finally, there’s a fabulous

piece on ‘the obsession’ of Laura in

which contemporary historians and film makers affectionately wax about the

influence of the film. We also get a theatrical trailer. Bottom line: very

highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

3.5

Comments