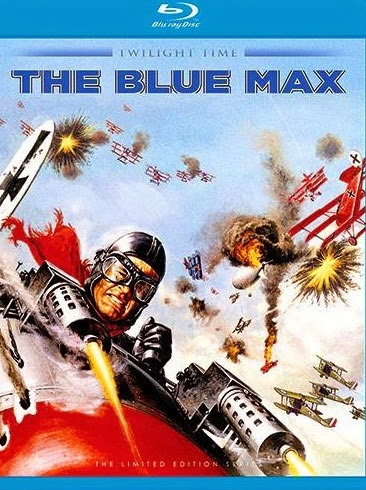

THE BLUE MAX: Blu-ray (2oth Century-Fox 1966) Twilight Time

Some 39 years

separate William Wellman’s seminal, Oscar-winning, Wings (1927) from John Guillermin’s The Blue Max (1966); the latter, a magnificently mounted roadshow

war epic in Cinemascope and DeLuxe color, featuring some fairly impressive

aerial stunt work to counterbalance its deathly dull back story about an elite

force of German flyers. The film never lacks credibility – its’ forgivable

cheats on actual period aircraft used in the movie expertly masked by Wilfrid

Shingleton’s tremendous production design and Fred Carter’s equally splendid

art direction; both first rate and awe-inspiring . These assets have been

captured for posterity in Douglas Slocombe’s jaw-dropping cinematography and

infrequently interpolated with Jerry Goldsmith’s somewhat imperious underscore,

calling out the leitmotif of ‘Deutschland über alles’ without

actually playing that song. The movie’s tagline ‘there was no quiet on the western front’ is, of course, a rather

obvious reference to another iconic WWI Oscar-winner made by Lewis Milestone in

1930.

In hindsight, The Blue Max is an exemplar of a

certain era in movie-making when big, bloated spectacles competed for box

office cache. And in many ways, The Blue

Max fits perfectly into 2oth Century-Fox’s great pantheon of wartime

pictures dedicated to the deconstruction of heroism, viewed from the

perspective of its damaged human participants; a tradition begun by production

head, Darryl F. Zanuck with Twelve

O’Clock High (1949) and carried all the way through to Zanuck’s personally

supervised combat epic, The Longest Day

(1962); the gloss and gallantry increasingly replaced by a more bitterly

introspective realization about the genuine toll, aftereffects and fallout

inflicted on the human psyche. Indeed, it was Zanuck who covetously snatched up

the rights to Jack D. Hunter’s novel, infusing the screen version of The Blue Max with all the chutzpah of a

bona fide testimonial, or perhaps epitaph befitting the ‘great war’.

The Blue Max is undeniably big. But it lacks that certain je ne

sais quoi all its predecessors had in spades; particularly Wings. William Wellman’s feats of aerial daring on Wings are unlikely to be surpassed. In contrast, Darby Kennedy’s stunt

coordination in The Blue Max is stimulating,

yet only in a class by itself if one hasn’t seen Wings beforehand. Wellman had his stars perform their own stunts

with heavy cameras mounted onto their biplanes; a debatably foolhardy endeavor

with the real threat of severe injury or death constantly looming from the

peripheries of the screen. By comparison, Kennedy’s stuntmen perform some

death-defying midair maneuvers in The

Blue Max. Regrettably, however, these have been interrupted in the editing

process by inserts of the featured cast set against some fairly obvious and

terribly unconvincing rear projection; the blue-screen mattes blatantly

revealed and diffusing the impact of the genuine footage shot for real in

mid-air.

The Blue Max would be an effective piece of period drama – for it

provides the only comprehensive visual record of WWI in blazing color and

widescreen (neither at the film maker’s disposal between 1914 and 1918);

approaching the war from the ‘enemy’s perspective’ and critiquing what ought to

have been intricate discernment about the conflicted altruism/abject

callousness of these elitist pilots. Too bad the film is marred by an

exceptionally wooden recital from its star, George Peppard (refusing to adopt

anything like a German accent) as Corporal Bruno Stachel – the haughty and

wholly unscrupulous prig whose warped sense of chivalry prevents him from

becoming one of the war’s true heroes. The movie’s Stachel is not the character

derived from Jack D. Hunter’s celebrated novel. While screenwriters David

Pursall, Jack Seddon, Gerald Hanley have retained Stachel’s suppression of

deep-seeded insecurities about his modest upbringing, they have jettisoned his

chronic alcoholism (a source of empathy for the character in the book) and gone

for the more traditional cliché of the ‘ruthless German’; a blonde-haired, and very blue-eyed narcissist;

self-assured, yet simultaneously self-destructing under the weight of his own

arrogant desire to possess the Pour le Mérite; the highest order of merit afforded

any flyer in the German Air Corp. for racking up twenty confirmed kills or more.

The screenplay

also plays fast and loose with several key elements from the original story;

chiefly in its penultimate comeuppance for Stachel, tricked by General Count

von Klugermann (James Mason) into test-flying the new monoplane. Stachel’s

orchestrated crash and burn is witnessed by hundreds of spectators gathered at

the airfield during Germany’s steeply declining supremacy in the war. What no

one – except the audience – knows is that Klugermann has been informed of a

formal inquiry regarding Stachel’s claim of two kills that ought to have gone

to fellow flyer, Lieutenant Willi von Klugermann (Jeremy Kemp) – the general’s

nephew. This leaked information comes from Stachel’s spurned lover, the Countess

Kaeti (Ursula Andress) who also happens to be Von Klugermann’s wife.

Yet despite

Stachel’s unapologetic betrayals of Klugermann’s relations, Klugermann

begrudgingly sacrifices Stachel to save face. For it was Klugermann who first

recognized Stachel’s unprincipled greed rife for the exploitation, creating a

deity in the media from this most unworthy man – thus, giving Germany what it

needs (manufactured valor in place of the real thing). At least initially,

Stachel was up for perpetuating this great lie. After all, he desperately wants

that shiny symbol of freewheeling masculinity – the Blue Max - dangling about

his neck…but at what price? In the novel, Stachel actually murders Willi,

perhaps out of some implied vengeance perpetuated against his own class - the

‘fat aristocrat’ snuffed out by this lower class upstart and four-flusher. The

killing is further justified in Stachel’s mind by his discovery of Willi’s

affair with the rather promiscuous Kaeti. The movie is a bit more sentimental

about Willi’s demise. He is wastefully lost in a game of airborne chicken with

Stachel proven the better flyer – perhaps – though decidedly not the better

man.

Honor plays a

big part in The Blue Max – or

rather, its definition as reconstituted by the less than self-sacrificing. On

the nobler end of this spectrum is Stachel’s superior officer, Hauptmann Otto

Heidemann (given inner luminosity and weighty distinction by Karl Michael Vogler);

a true soldier as it were, setting personal distinctions aside for the good of

his country. There is built-in pride to this man, unqualified and pure; utterly

disqualified in Stachel, who refuses to abide under Heidemann’s tutelage and

dictums. Honor is more corruptible in

Klugermann’s mind – a distinguished military strategist not above misusing Stachel’s

egotism to serve a larger purpose – guaranteed to centralize his own stake in

this power struggle. Stachel’s lack of honor (indeed, he has only a remedial

comprehension of what that word means) is ultimately what gets him killed;

enterprising motives blindsided by jealousy and the most undiluted form of raw,

self-destructing ambition.

Yet, The Blue Max takes an interminable amount

of time to get to these more lascivious interior motivations. Presumably to establish

the movie as an epic, we begin with an extended prologue; a perilous trek across

the war-ravaged, barb-wired front. Bruno Stachel (George Peppard) is the sole

survivor of a particularly brutal gas attack in the trenches. Spying his first

aircraft sailing overhead, Stachel is immediately stirred by this dream-like

phoenix to transfer from the infantry into the German Air Corp. Joining an

elite squadron of flyers in Spring, 1918 – the tail end of the war – Stachel is

determined to win Imperial Germany's highest military decoration for valor, the

Pour le Mérite (a.k.a. Blue Max). But time is running out. The war may be over

in a matter of weeks. Worse for Stachel, is his modest background, a chronic

source of embarrassment. His fellow

pilots all come from privilege; particularly, Willi von Klugermann (Jeremy

Kemp), the nephew of noted high-commanding officer, General Count von

Klugermann (James Mason).

The squadron

is presided over by Hauptmann Otto Heidemann (Karl Michael Vogler); an upperclassman

of the old school to whom chivalry is an essential ingredient for winning the

war. But Heidemann’s integrity conflicts with Stachel’s heartless fortitude.

Only one thing matters to Stachel – the Blue Max. He’ll have it by any means at

his disposal. Willi’s attempts to befriend Stachel are met with steely resolve

(Peppard unable to punctuate his sparse dialogue as anything better than the

vaguely absurd petulance of a fairly psychotic loner). Stachel makes it known

his idolized hero of the skies is Von Richthofen (a.k.a The Red Baron, and

briefly glimpsed in a performance by Carl Schell). Stachel, of course, fails to

realize the public relations machinery behind such deified supermen, largely

manufactured to help propagandize the cause into victory.

On his first

mission Stachel - flying a Pfalz D.III - manages to down a British S.E.5. But

this early victory is ignored as an ‘unconfirmed kill’ by the high command

because no witnesses were present. Rather peevishly, Stachel berates Heidemann

– his personal scoring evidently far more important to him than any investment

in the dogfight as an integral part of the squadron. Stachel spends a windswept

rainy afternoon and evening scouring the French countryside for the plane’s

wreckage to officially document his claim. He is unsuccessful, however, and

returns to the base to find Willi in his room with a fresh bottle of brandy.

On his next

mission, Stachel goes after an Allied observation aircraft, disabling its’ rear

gunner. Instead of downing the vulnerable plane, Stachel signals the pilot to

land – presumably to be taken as his prisoner. However, as both planes approach

the airfield, the gunner stirs and Stachel has no choice but to finish what he

started. He downs the plane in a fiery ball of flame, Heidemann suspecting

Stachel simply of committing cold-blooded murder to earn his first ‘confirmed’

kill. While the mood between Heidemann and Stachel will increasingly becoming

strained from this moment on, word of mouth reaches Klugermann, who has arrived

at the base to award Willi the Blue Max. Klugermann is a wily politico. Sensing

that Stachel’s greed can be manipulated to suit his own purpose, the

manufacturing of yet another hero to help propagandize the war, Klugmann superficially

befriends Stachel. At the presentation ceremony, Klugermann’s wife, the

Countess Kaeti takes a passing interest in Stachel – unrequited at first, her

rather transparent affair with Willi obvious to everyone present.

Stachel’s next

moment of military distinction is quite accidental; shot down after defending a

Fokker Dr.I attacked by a pair of British fighters. Back at the airfield,

Heidemann introduces Stachel to the man he inadvertently saved; none other than

his idolized war hero, Manfred von Richthofen (Carl Schell) – the Red Baron.

Von Richthofen is congenial, offering Stachel a place of distinction in his

squadron. It’s a plum role, and one any of the other pilots would not hesitate

to accept. Perhaps wisely deducing that

under Von Richthofen’s command he would forever be overshadowed by the legacy

of such a legend, Stachel politely declines this offer, electing to ‘improve

himself’ at his current post instead. Temporarily sidelined with a superficial

wound, Stachel is whisked away to Berlin under Klugermann’s auspices, briefly

introduced to Heidemann’s wife, Elfi (Loni Von Friedl); a nurse who poses with

Stachel for staged photographs. In private, Elfi confides in Stachel wishes for

her husband’s retirement from the Air Corp.

Klugermann

arrives just in time to preside over the gaggle of sycophantic reporters he has

hired to capture this fictitious moment for posterity. Stachel doesn’t care

much for this exploitation. But Klugermann sweetens the deal by inviting

Stachel to his estate for a grand party hosted by his wife; quite aware Stachel

is to be Kaeti’s latest sexual conquest. The

‘love’ scenes in The Blue Max

are tantalizingly eerie; director Guillermin and cinematographer, Douglas

Slocombe conspiring to evoke a queer, devouring and chaotic pas deux. Kaeti and

Stachel’s renewed sexual détentes incorporate obscure lighting and severe

tilt-pans, suggesting more voracity in their shared appetite for debauchery

than any mutual affection.

Upon Stachel’s

return to the base, Willi jealously confronts him about Kaeti; Stachel unable

to conceal his satisfaction with a grin and a chuckle, believing his cock of

the walk has surpassed Willi’s prowess in the bedroom. The next afternoon,

Stachel and Willi volunteer for a reconnaissance mission. Once in the air, they

are attacked by a squadron of British fighters. Stachel’s guns jam. But Willi dutifully

picks off a pair of British flyers, then another in hot pursuit of Stachel’s

plane. The other fighters quickly disband. But Willi now engages Stachel in a

game of aerial chicken; repeatedly dive-bombing between the stone pillars a

narrow bridge and encouraging Stachel to do the same. These low passes place

them precariously close to the trees and nearby, half-bombed out tower. Unable

to resist the dare, Stachel matches Willi dive for dive, anteing up the stakes

by flying between an even narrower span, thus forcing Willi to do the same to

prove his stealth. Tragically, Willi clips

the tower with his landing gear, loses control and crashes into some nearby

trees.

At base,

Stachel reports Willi’s death to Heidemann, but takes credit for the two downed

enemy aircraft Willi dispatched, despite an investigation of his plane revealing

only forty rounds used before his gun’s jammed. Suspecting foul play, Heidemann

refuses to file Stachel’s report. Instead, he goes to Klugermann with his suspicions

about Stachel. Klugermann is sympathetic, but explains to Heidemann that

Stachel’s kills will be confirmed. Heidemann refuses to be a part of this

charade, resigning his commission and pleading with Klugermann to appoint him

to a desk job. At Willi’s burial, Stachel and Kaeti exchanged panged

expressions that ominously register both fear and excitement. Later that

evening, Stachel and Kaeti meet again to indulge their sexual whims, Stachel

quietly confessing to her that he lied about Willi’s kills.

On his final

tour of duty with the squadron, Heidemann orders Stachel not to engage nearby

enemy flyers. But Stachel, nearing the magic number of twenty necessary to

secure him the Blue Max, defies these direct orders. As a result, half his

squadron is lost in the perilous dogfight that ensues and Heidemann places

Stachel under arrest. Once again, Klugermann intercedes on Stachel’s behalf,

telling Heidemann that the people demand a hero – particularly since the tide

of the war has turned against Germany. Sensing the beginning of the end, Kaeti

elects to run off to Switzerland, encouraging Stachel to abandon his dreams and

join her instead. Stachel’s rebuke of this offer incurs Kaeti’s wrath. Going

above her husband’s authority, Kaeti leaks information about Stachel’s

dishonesty to Germany’s high command; his entire record suddenly brought into

question and slated for an official inquiry yet to follow.

Klugerman

expedites Stachel’s awarding of the Blue Max by Germany’s Crown Prince (Roger

Ostime) in a highly publicized event on the airfield. Too late the Field

Marshal telephones Klugermann to cancel this ceremony. Making his own inquiries

as to how the reported information was leaked, Klugermann is informed that

Kaeti is the instigator. It now becomes clear to Klugermann what sacrifices

will have to be made in order to spare the Air Corp its reputation, but also to

save his own skin. Klugermann instructs Heidemann to test fly the new monoplane

– an aerial assignment that ought to have gone to Stachel, immediately

following the award’s presentation.

Heidemann reluctantly

complies, flying the unproven aircraft. But he is barely able to make his

landing; informing Klugermann that the plane is a ‘death trap’. Klugermann now

encourages Stachel to do ‘some real

flying’ in the unsafe aircraft. Unaware of the plane’s deficiencies, Stachel’s

ego takes over. He takes off into the wild blue yonder from which Klugermann

understands he will likely not return, performing a series of death-defying

aerial maneuvers high overhead. Tragically, Stachel is unable to land the

monoplane. He crashes off in the distance in a hellish ball of flames as the

terrified crowd rush toward the wreckage; Klugermann calmly taking his wife by

the arm and ushering her into a nearby car, coldly explaining to her that they

will be late for dinner.

The Blue Max is impressively mounted, but a rather stodgy big

screen experience to get through. Ironically, its’ dower ending isn’t the

problem. Rather, at 156 minutes, the movie tends to outstay its welcome whenever

any of the aforementioned fly-boys feet are firmly on the ground. The

screenplay isn’t entirely to blame. Another actor might have made something

more of Lt. Bruno Stachel than George Peppard’s starched-britches psychopath.

It really is a one-dimensional and fairly ugly performance we get from Peppard

and it’s a tough sell from the moment we are introduced to his wholly

inscrutable though utterly devious schemer right up until the penultimate

moment of his mind-numbing fireball impact with terra firma.

The outstanding

performances herein belong to Karl Michael Vogler, as Heidemann, and to a

lesser extent, Jeremy Kemp’s Willi Von Krugermann. The death of Willi almost immediately

following the movie’s intermission leaves Volger’s noble man of action to do

the heavy lifting – at least, from a dramatic standpoint. Volger is more than

up to the challenge. Except that the screenplay negates Heidemann’s importance

shortly thereafter to very minor support in the second half, leaving the

audience to grapple with the peculiar lover’s triangle of Stachel, Kaeti and Gen.

Krugermann – the latter, what nature – or at least, the movies – abhor: the

enervated failure of masculine virility.

When excised

of their rather hammy inserts shot against a blue screen, many of the flying

sequences are quite impressive. Douglas Slocombe’s camera soars into the clouds

with stealthy precision, capturing a bird’s eye view of these aerial theatrics

designed to enthrall – and they do. Still, for authenticity I prefer ‘Wild

Bill’ Wellman’s sepia tinted and B&W sequences in Wings to the expansive Cinemascope footage shot for The Blue Max. Call it a bias. But I’ll

take Wellman’s classic to Guillermin’s overblown melodrama any day of the week.

2oth

Century-Fox’s hi-def transfer on The

Blue Max via Twilight Time is generally a cause for celebration. The 1080p

transfer is sharp and finely detailed with exceptional clarity throughout –

proof that when the studio wants to, it can remaster a catalogue title to yield

rather stunning results. What is less acceptable is the overall teal bias. A

goodly number of Fox’s Cinemascope movies transferred to Blu-ray have adopted

this unsettling color imbalance. Early sequences in The Blue Max appear to suffer more so from this grossly over-saturated

teal hue. Even the whites of Peppard’s eyes and his teeth have adopted a

slightly bluish tint. I’m not certain whether this is an issue of improper

color balancing during the hi-def mastering process or a case of early vinegar

syndrome plaguing the original camera negative.

Either way, it’s

problematic; the Germans grey trench coats are greenish/blue. Flesh is ever so

slightly leaning toward the orangey palette, while reds appear greatly muted. This

transfer favors blues, greens and beiges. Again, it isn’t a question of

color-fading, but of an inaccurately balanced spectrum. Never having seen The Blue Max in theaters I cannot state for certain this isn’t how

the movie looked back in 1967; although I can’t imagine so heavy a slant toward

teal ever being a part of The Blue Max’s

original presentation.

Despite my

concerns herein, the odd color isn’t a deal breaker in my opinion. It just

looks off, occasionally to the point of distraction. On the plus side is the

remastered 5.1 soundtrack, showcasing Jerry Goldsmith’s superb score. Wow – and

– ‘thank you’! Just fantastic. Ditto and kudos to Twilight Time for providing

us with an isolated track. Herein, we also get another treat: a second isolated

track featuring alternate music cues with insightful commentary provided by

historians Jon Burlingame, Julie Kirgo and Nick Redman. Great stuff! Finally,

Kirgo once again fleshes out the movie’s backstory in Twilight Time’s much

appreciated liner notes – treasured tidbits other studios seem to have entirely

given up on providing with their Blu-ray releases.

Bottom line: The Blue Max isn’t an exceptional war

movie in my opinion. But it has been hand-crafted with a high level of

competence and an undeniable stellar degree of historical accuracy. As Kirgo’s

notes point out – the movie has inspired scores of film makers toward mimicry

of its stylistic elements. It should equally impress most war buffs, aficionados

and the layman merely looking for a good solid way of passing a few hours in front

of the TV. Bottom line: recommended.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

3

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

3

Comments