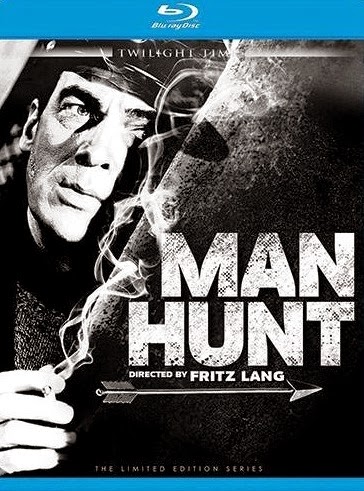

MAN HUNT: Blu-ray (2oth Century-Fox 1941) Twilight Time

With its ubiquitous

deep

chiaroscuro lighting, some magnificently performed suspense sequences (at times,

shot almost in total silence), Fritz Lang’s Man Hunt (1941) arguably, remains the quintessential noir political

crime/thriller; an odd amalgam, transfixing and austere; so effective without

hyperbole or cliché, in essence, it has not dated since its debut. Who better

than Lang to know the threat of Nazism before its grim and uncivilized

methodologies were unleashed upon the unsuspecting outside world: Lang, an

impassioned Jewish filmmaker (ironically, wed to a Nazi), but forced to flee his

homeland after being asked by Hitler’s right hand, Joseph Goebbels, to organize

and manage der Führer’s propaganda machine. In hindsight, Man Hunt is as lurid as it proves prolific; based on Geoffrey

Household’s 1939 masterpiece, Rogue Male; a novel of such clairvoyant

projections it garnered rave critical reviews in both the U.S. and Britain. In

Hollywood, however, such enthusiasm was decidedly tempered, thanks to an

unwritten pact with the U.S. government, effectively forbidding any movies

meant to stir America from its’ predominantly isolationist policies.

However, Fox

mogul, Darryl F. Zanuck was never known to shy away from a challenge. With his

writer’s instinct, he also knew a very good property when he read it; and

Household’s novel – first serialized, then published as a whole – had already

caught the popular zeitgeist as a best seller. The times were rife to stand

apart and alone…well, sort of…to make a picture effectively challenging the

status quo. Man Hunt can effectively

be called Fritz Lang’s ‘first’ American masterstroke; shot, edited and

unleashed to favorable reviews and respectable business in a record three

months – a very timely piece of wartime propaganda, imbued with Lang’s

unmistakable bite. Lang knew too well the perils of Nazism, having taken the

proverbial night train out of Munich days before the borders were officially

closed. What atrocities had already

begun to unfurl behind Hitler’s policed stronghold would remain a secret for a

little while longer, the blitzkriegs yet to stealthily extend like the bony fingers

of Dr. Caligari across the European front, plunging half a hemisphere into

flames.

And Lang,

unlike say, John Ford (first asked by Zanuck to helm the production - but

declined) is unapologetic in sharing his bluntness of anti-German sentiments

throughout the rechristened Man Hunt.

Clearly, Lang was unafraid to illustrate this for the rest of the world. If the

director’s opinion of the ‘good Nazi’ (superbly characterized by a crew-cut,

monocle-wearing, perpetually scowling George Sanders) seems like a bad cliché

of an even more awful villain, it’s only because we’ve seen this sort of

caricature again and again since, in virtually every American movie having at

least one Nazi; the brainwashed, dark and soulless gargoyle, obsessively devoted

in his calculating ruthlessness. Lang

may not have invented this image, but he certainly ensconced its iconography in

Man Hunt; Sanders speaking a few

lines of German at the beginning of the movie with such clipped brusqueness, he

all but convinces us of that globular determination more artful and nefarious

than even the devil’s own.

Lang has less

success convincing us of Walter Pigeon’s Englishness as Captain Alan Thorndike,

a good-time Charlie simply out for a ‘sporting

stalk’ of der Führer when he is inadvertently captured and taken to Major

Quive-Smith (Sanders) for interrogation and, presumably, extermination. Like

Fritz Lang, Pigeon’s career in Hollywood had yet to hit its stride as the ‘other half’ of an enduring screen team

with the eloquent Irish lass, Greer Garson. Although Pigeon’s tenure in the

movies was already considerably longer than Lang’s – if equally marginalized – for

both men, Man Hunt would prove a

major graduation into the big leagues; particularly for Lang who had helplessly

watched as his reputation as Germany’s premiere auteur all but evaporated in

sunny California. It’s almost a given Walter Pigeon had more box office cache

than Fritz Lang at the time Man Hunt

went into production; Lang’s standing as the creator of such iconic German classics,

Metropolis (1927) and ‘M’ (1931) never equating to the sort of

celebrity he felt was owed him state’s side. Arguably, Lang would never

recapture his former glory, despite the fact some highly competent movies were

made as Lang frequently railed against Hollywood’s assembly line system for

manufacturing art.

Man Hunt would also prove a showcase for co-star, Joan

Bennett, cast as Jerry Stokes – rechristened a seamstress in the movie from the

novel’s original prostitute at the behest of the Production Code. They even

went so far as to predominantly feature an old Singer sewing machine as part of

the props in Jerry’s crummy little flat, although her digs remain located near

the wharf on the seedy side of town where one profession, rather than the

other, would be more likely to flourish.

Fritz Lang was

hardly an actor’s director. In fact, he proved exacting to the point of

maniacal. Yet, Joan Bennett thrived under his tutelage, so much that the

actress was instrumental in helping this temperamental showman land his next

big gig over at RKO, The Woman in the

Window (1944) after a series of high profile flops once more threatened to

knock Lang’s standing back into the stone age. Their farewell project together,

Secret Beyond the Door (1947) is

hardly a classic, hampered more by a menial screenplay than anything else. But

by then a mutual respect had blossomed between these two. It is rumored –

though unconfirmed – Bennett and Lang were having an affair on the set of Man Hunt. Perhaps – perhaps not. Lang

was hardly anyone’s idea of a lady’s man and never thought of himself as such.

But he was a powerful presence and such strength of character does parallel the

intoxication of a magic elixir for some women.

Man Hunt feeds off Lang’s predisposition for themes of

persecution; an innocent man betrayed by circumstances beyond his control and

forced to flee into increasingly claustrophobic environments. In some ways,

this is also the modus operandi of the conventional (though, as yet

unestablished) film noir movement. But Lang gives us much more than the stock

and trade noir in its penchant for criminal activity and menace lurking around

every fog-filtered street corner, under every murky bridge, or seeping/creeping

out from each inky shadow; the perpetually rain-soaked cobblestone barely lit

by the weak flicker of gaslight. No, Man

Hunt devours its audience in the perversity of political intrigues, matched

and married to yet another festival of the macabre – the sadism of a nation

already begun to implode on its own self-professed smug superiority. As such, Man Hunt exudes a sort of disquieting moody

magnificence we don’t see in movies anymore; primarily evoked in its riveting

visual flair (Arthur C. Miller’s cinematography is peerless); master wit,

Dudley Nichols providing the narrative substance to effectively back it up.

In Man Hunt, Capt. Thorndike is a trapped

animal, surrounded by spurious agents working for the Gestapo who are hell-bent

on delivering him to Adolf Hitler like a prized trophy – dead or alive – or, if not,

then using his signature on a forced confession to frame England’s government

as the true aggressors, in order to kick start the Second World War. Remember,

again – all this espionage was first conceived by author, Geoffrey Householder

in 1937; a full year before the Anschluss (Hitler’s peaceful annexation of

Austria); Householder’s novel published the same year Hitler invaded Poland. In

1941, Man Hunt was still very much ‘of the moment’: its assassination plot

coming even before the Allies had…well…allied against the Axis. So, in one

respect, Man Hunt is fairly fanciful;

its lone gunman thwarted by an unholy twist of fate in his nobler motives to

murder a madman (thereby sparing us from WWII); the resultant chase for this

man with the scar on his face leading from Berchtesgaden to London where, so

Lang would have us believe, there were even more Nazis (albeit, ones with thick

cockney accents) diligently working to dismantle and discredit libertarianism.

Lang’s great

gift to Man Hunt is, of course, his

ability to make even the most innocuous street corner and byway appear as

something of a seismic rupture in the earth’s crust, our hero always one false

move away from becoming entombed in this contemporary Dante’s Inferno. In fact,

the penultimate moment of Man Hunt

has our hero trapped inside a very narrow cave, an inner-earth purgatory –

literally – spared suffocation at the last possible moment by using his

cunning; his motive – revenge – most foul and equally as bloody (he leaves

George Sander’s Nazi lying face down in the swampy mud with an arrow pierced

through his eardrum). In between the

botched attempt on Hitler’s life and Man

Hunt’s finale (Thorndike parachuting back into Germany with his trusty

rifle, under the apocryphal notion his will be the bullet to eventually

assassinate Hitler), Fritz Lang revels in the salaciousness of the exercise. In

essence, Man Hunt is an extended chase

across Europe with Thorndike forced to suffer a conversion of motive; his loner’s

quest to splinter the Nazi stranglehold of the continent by eliminating its

figurehead, distilled into a more highly personal vision quest, predicated on

vengeance for the unanticipated death of his beloved, Jerry.

Much has been

made of the fact, Jerry and Thorndike never make it to even first base in their

romance – interrupted either by circumstance or casually thwarted by

Thorndike’s increasing inability to commit to this much younger paramour who so

obviously desires more from him than money, gratitude or even their infrequent

casual embraces. However, Thorndike’s approach is far more paternal than

lascivious. He sleeps on Jerry’s cot, dries her tears with a soft linen hanky

and tenderly tweaks her nose and cheek, plying her with tender words, meant more

in guidance than love. Thorndike even nobly insists Jerry remove herself from

the equation before Quive-Smith and his Nazi goon squad get wise to their

affiliation. Ironically, it is Thorndike’s reluctant decision to involve Jerry

in his escape plans – adopting her last name ‘Stokes’ as his cover and living obscurely

in the countryside, using Jerry as his courier, that gets her killed. The

realization his sins have been visited upon this unsuspecting innocent turn

Thorndike from wartime crusader toward steely-eyed vigilantism. By the end of Man Hunt we no longer fear for

Thorndike’s safety from the Nazis, but sincerely wonder if the Nazis have yet

to realize what a faceless soldier of (mis)fortune they’ve unwittingly

unleashed upon themselves by removing the one impediment – a woman’s love –

that might have softened Thorndike as more of mensch and less the killing

machine.

Man Hunt begins with Capt. Alan Thorndike’s ill-fated ‘sporting stalk’ of Adolf Hitler, crawling

through some dense and heavily guarded underbrush just beyond the Nazi

stronghold near Berchtesgaden. His subject framed within his telescopic sight,

Thorndike’s perfect kill is thwarted by a falling leaf, notifying one of the

guards to his presence. The pair struggle to regain control over the rifle and

Thorndike gets off a wild round. Pummeled by his Nazi captors, Thorndike is

dragged into the sparsely decorated sitting room of Major Quive-Smith, in the

process of entertaining a game of chess with the doctor (Ludwig Stössel); a

sort of portly and balding, Josef Mengele. A fellow sportsman, Quive-Smith is

at first filled with admiration for Thorndike’s ability; also his sheer

chutzpah to get so close in his assassination attempt. Thorndike offers a

half-hearted explanation – compelled by the art of the hunt, but having no

obvious reason or passing interest for that matter, to actually ‘kill’ Hitler.

It was all just a game.

Quive-Smith

isn’t buying Thorndike’s act. Instead, he suggests Thorndike as a spy for Her

Majesty’s government; a claim Thorndike vehemently denies. Quive-Smith coolly explains

that Thorndike may have his freedom immediately; deposited on a plane bound for

England, but only if he signs a forced letter of confession. Thorndike refuses and

Quive-Smith orders him taken to be tortured for several days on end, repeatedly

dragged back into his parlor in ever-increasingly worse condition and asked to

recuse himself of his supposedly more altruistic motives. Still, Thorndike

refuses. Furthermore, he has the audacity to warn Quive-Smith that should he

die suspiciously abroad his brother, Lord Gerald Risborough (Frederick

Worlock) - a very important diplomat - will make it his mission to launch

formal inquiries likely to create a stir between the two – as yet, tenuously

peaceful – governments. Quive-Smith is not so easily fooled. In fact,

Thorndike’s threat gives the wily Nazi a splendidly ghoulish idea; to toss

Thorndike from a precipice in the dead of night, thereby making his murder look

like a tragic accident.

Alas,

Thorndike’s knapsack gets lodged in a tree branch on the way down, breaking his

fall. The next day, Quive-Smith and the doctor pretend to go on a hunting

excursion, certain they will ‘accidentally’

discover Thorndike’s body in the underbrush at the base of the cliff. Instead,

there is no sign of him; Thorndike – severely battered and bruised, but

otherwise unharmed, having skulked into the dense foliage, crossing a shallow

stream to throw Quive-Smith’s hunting dogs off his scent. Regrettably, the

hunting party finds Thorndike’s coat and passport among the debris. Quive-Smith

files the latter away for safe keeping. Making his way to port, Thorndike

steals a rowboat. A German patrol notices his abandoned vessel adrift near the

wharf, Thorndike already swum to a nearby Danish trawler after overhearing its

captain, Jensen (Roger Imhof) and the cabin boy, Vaner (Roddy McDowell)

conversing in English. Exhausted, Thorndike collapses on the trawler’s deck,

concealed by Vaner, who is British and therefore compassionate towards his

countryman.

The ship is

searched by Quive-Smith and the Gestapo, Thorndike managing to outfox the lot

by hiding in an undiscovered hold; its trapdoor hidden beneath a rug in the

captain’s quarters. Not even Jensen knows Thorndike is aboard. Too bad the

Nazis have another plan afoot, ordering Jensen to take on an imposter; the

spurious ‘Mr. Jones’ (John Carradine) masquerading as Thorndike by using his

passport. Unaware, Jones is not Thorndike, Jensen sails his ship to England.

Fritz Lang spares us the tedium of daily intrigues; instead using a few

well-placed scenes to establish the constant peril the real Thorndike and Vaner

find themselves in; Jones menacing from the peripheries, though quite unable to

pinpoint his suspicions. The ship docks in London, and after making one last

attempt to intimidate Vaner, Jones disembarks; leaving behind a pair of Nazi

stooges to quietly observe the vessel from the docks.

Vaner steals

the first mates pea coat and sweater for Thorndike, who disembarks the ship

shortly thereafter, utterly confident his return to England has been a success.

Alas, it only takes a few brief moments for Thorndike to realize he is being

followed by Jones and his goons, narrowly avoiding capture several times and

finally ducking into a dreary apartment building where he inadvertently

stumbles upon Jerry Stokes, who is leaving her flat for a quick drag in the

foyer. After subduing her screams,

Thorndike forces his way into Jerry’s apartment; the edgy détente between these

two gradually softening to the point where Jerry reluctantly agrees to loan

Thorndike necessary cab fare to visit his brother, Lord Risborough.

Lady

Risborough (Heather Thatcher) is a prude. But she agrees to entertain Jerry in

the parlor while the men hurry into the study to debate Thorndike’s future

course of action. Lord Risborough informs Thorndike the Nazis have already

anticipated his contacting him, pretending to be Thorndike’s friends come to

call for old time’s sake. Risborough suggests Thorndike cannot reenter the

country without his passport: to do so will cause the German ambassador to

assume the attempt Thorndike made on Hitler’s life was, in fact, sanctioned by

the British government, thus giving the Germans the perfect scapegoat and alibi

to declare war on England. To quell this threat, Thorndike agrees to virtually

disappear, making plans to go abroad at the earliest possible convenience.

Before leaving his brother, Thorndike asks for a loan of five pounds. But this

he gives almost immediately to Jerry; partly to repay her the moneys he

borrowed; also, to sincerely thank her for the kindness and faith she has shown

towards him.

Thorndike also

agrees to buy Jerry a new hatpin for the one she lost while helping dodge the

Nazis. The new pin is silver and in the shape of Cupid’s arrow, the shopkeeper

suggesting the obvious; Jerry is already desperately in love with Thorndike. For the briefest of moments, Thorndike and

Jerry are obtusely happy together. It’s not to last however, as Quive-Smith

arrives in London to take up the man hunt. After Thorndike attends his solicitor,

Saul Farnsworthy (Holmes Herbert) at his downtown offices, the Nazis once more

pick up his scent Thorndike and Jerry separate, he descending into the bowels

of the Underground, jumping from the isolated station platform onto the tracks

and running into the darkened recesses of the tunnel.

In one of

Lang’s best moments of high intensity suspense, Jones – who is, as yet, unaware

how close he is to discovering Thorndike’s hiding spot, removes a silver-tipped

knife from his rather innocuous looking walking stick. Confronted by Thorndike

in the tunnel, the two men struggle until Thorndike manages to electrocute

Jones after his blade touches the tracks. Regrettably, Thorndike forgets to

search the body before running off; its discovery by the police later revealing

Thorndike’s passport still inside Jones’ coat pocket. Since the body was struck

and run over by a train, no positive identification is possible. The police

naturally assume the deceased is

Thorndike. Officially dead, Thorndike can now be pursued by the Nazis and

killed without anyone ever knowing any different. After all, Thorndike’s

already been declared legally dead.

Sneaking back

to Jerry’s flat, Thorndike instructs the heart sore girl to remain behind. She

can no longer be involved in his death-defying intrigues. Instead, he instructs

Jerry to have his brother send him a letter in three weeks, care of the Lyme

Regis post office. Jerry bids her would-be lover farewell on the bridge, their

one chance for a passionate kiss goodbye thwarted when a bobby mistakes Jerry

for a girl of the streets who is pestering a gentleman as part of her stock and

trade. It’s a fascinating moment in the movie; Jerry playing along with the

officer’s insinuations so as not to blow Thorndike’s cover; returning to her

flat a short while later, only to be startled by Quive-Smith and his cronies,

awaiting her return.

Meanwhile,

Thorndike hides in a cave not far from Lyme Regis, assumes the name of Stokes

and growing a beard as camouflage. He returns to the post office three weeks

later. Inquiring about a letter for Stokes, Thorndike suddenly becomes aware of

the postmistress’ (Eily Malyon) erratic behavior. She even manages to sneak into

the back for a brief moment to alert one of her helpers to hurry off. To what

purpose? We’re not exactly sure, and neither is Thorndike, as he absconds with

the letter back to his hideaway, barricading himself inside the cave with a

bolder cleverly lodged with a heavy wooden branch as its failsafe, only to

discover the letter is not from Jerry or Lord Risborough, but Quive-Smith, who

has also managed to tail Thorndike to the cave.

Quive-Smith

informs Thorndike there is no escape. He has obstructed the cave entrance from

the outside with another bolder and branch. Quive-Smith now gloats with

sinister pride as he tells Thorndike how Jerry died – ‘falling’ out of her

second story window. As Thorndike clearly remembers how he himself was pushed

from the cliff by the doctor, he knows the Nazis also murdered Jerry; proof now

given to Thorndike by Quive-Smith through one of the air shafts; Jerry’s beret

with Thorndike’s silver arrow pendant still affixed to it. Quive-Smith gets

Thorndike to admit his initial ruse about a ‘sporting stalk’ was just that. Thorndike had every intention to

assassinate Hitler, though not on orders from his government. Quive-Smith gives

Thorndike an ultimatum; sign the letter of confession or be suffocated inside

the cave. Instead, Thorndike uses his wits to quickly construct a bow and arrow

from wooden planks, using Jerry’s silver tipped pendant as its piercing head.

He gets Quive-Smith to remove the bolder blocking his escape, sinks the arrow

into his arch nemesis’ temple. Believing Quive-Smith is dead, Jerry emerges

from the cave only to be shot and gravely wounded by the dying Nazi.

The resultant

montage that concludes Man Hunt

takes us cyclically back to the movie’s prologue ‘somewhere in Germany’; beginning with a series of hallucinatory

snippets showcasing Thorndike’s gradual recovery from Quive-Smith’s gunshot;

his enlistment in the RAF and his disobeying direct orders by leaping with a

parachute and his trusty rifle from a war plane flying over Germany; a voice over

narration declaring that “Somewhere in

Germany” a man is out for justice (i.e. revenge rechristened ‘as justice’) because it is now in

service to his country. It’s a symbolic – and not altogether satisfying –

conclusion to our story; Thorndike standing in for the Allied Forces, never to

rest until Adolf Hitler is either taken captive or lying in his grave.

Until this

finale, Man Hunt remains an

exhilarating thriller, by far one of the earliest – if not the first – to take

a stand against Germany’s growing presence in the European theater and its

ominous premonitions of another looming world war. We can forgive Lang his

casting of Walter Pigeon because the actor is so marvelous in his delivery, so

utterly charming and, at times, even devil-may-care, so eager to please, he

easily wins our hearts – if not as the stoic Brit with stiff upper lip and chin

stuck out, then as the unconsciously American objector to tyranny, thrust like

a hothouse flower transplanted to the studio back lot milieu of a

pseudo-London, complete with narrow cobblestone and fog-machine laden streets,

gorgeously backlit by Arthur C. Miller’s cinematography.

Joan Bennett

is delicious as the winsome cockney tart whose heart believably melts like

butter at the very first sight of her scruffy Lochinvar. Bennett’s expressive,

sad eyes betray her youth. She was thirty-one at the time. Yet, Bennett gives

us this tarnished angel as a girl who has lived – and not well, though

nevertheless by her wits. Jerry has no illusions about who or what she is. And

yet, Bennett reveals a tender, wholly believable naïveté, particularly where

Thorndike is concerned; the very flaw in her good nature contributing to her

own undoing.

Fox’s resident

composer, Alfred Newman provides the capper for this stylish noir with a

magnificent score, an uncredited assist from David Buttolph; effortlessly

interpolating thematic elements of the daring adventure, tender romance and

ominous strains of a traditional chase-thriller. It all works, spectacularly well,

in fact. Ultimately, however, the stars that align significantly pale to Fritz

Lang’s overriding directorial influences. One can argue most directors have a

personal imprint or style that undeniably shines beyond the material.

But Man Hunt is prototypical Fritz Lang;

the director’s not so subliminal smite against the upper classes revealed

Lang’s wicked contempt for the aristocracy at large. The ‘haves’ are never lovingly represented in a Fritz Lang movie. But herein,

Lang plays them strictly for laughs – particularly the Brits: Heather

Thatcher’s delightfully rigid, socially wounded prig, quite unable to reconcile

her biases toward Joan Bennett’s playful and ironically virgin-esque

guttersnipe, at least, until our hero coaxes the haughty Lady Alice down from

her tuffet with a sly wink and a genial nudge.

Man Hunt is vintage A+ Lang in other ways too; chiefly in

creating a possessively dark and disturbing world, so absent of any moral code

(apart from survival of the fittest) or even ethical center of gravity that the

characters seem to exist and/or survive largely by happenstance. Fate is Lang’s

vindictive god, looming large above men of action, like Thorndike, and those

like Quive-Smith, utterly capricious in their singular thirst to destroy by

whatever means is currently at their disposal. George Sander’s Nazi Major is

the embodiment of bone-chilling efficiency; distilling the whole of non-German

humankind into a disposable and easily annihilated foe.

Finally, we

get Lang’s bleak notions about the war itself that, in hindsight at least,

turned out to be very ominous and clairvoyant, indeed. Man Hunt is a compact, if far-fetched spy story, expertly crafted

and even more surprising played to perfection by all concerned; unrelentingly twitchy

and morosely spellbinding. Penetratingly scripted by Dudley Nichols, Man Hunt also prefigures America’s

tsunami of Allied propaganda war movies soon to dominate cinema culture for

decades to follow. Today, it holds up remarkably well - and not merely as a

cultural artifact from this bygone epoch. Man

Hunt is fancifully sinister and intensely fulfilling.

We really need

to tip our hats to Fox Home Video and their limited edition Blu-ray release via

Twilight Time; a stunning 1080p 1.33:1 transfer, showing minimal signs of

age-related wear and tear. Prepare to be very impressed. This B&W image has

been superbly rendered in hi-def; the ‘wow’ factor in evidence immediately

following the main titles. Fine detail abounds – the image so refined we can

see minute textures in wood grain, hair, foliage and other background

information. Arthur C. Miller’s cinematography has been gorgeously preserved,

the tonality in the grayscale quite simply astonishing with pitch-perfect

contrast. We’ll also give kudos to the handsome DTS mono audio, perfectly

supportive of this dialogue-driven movie. Last, but certainly not least,

Twilight Time offers us an isolated score and a brief featurette on the making

of the film, as well as a theatrical trailer and the usual superb essay from TT’s Julie

Kirgo. Bottom line: very highly recommended.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

2.5

Comments