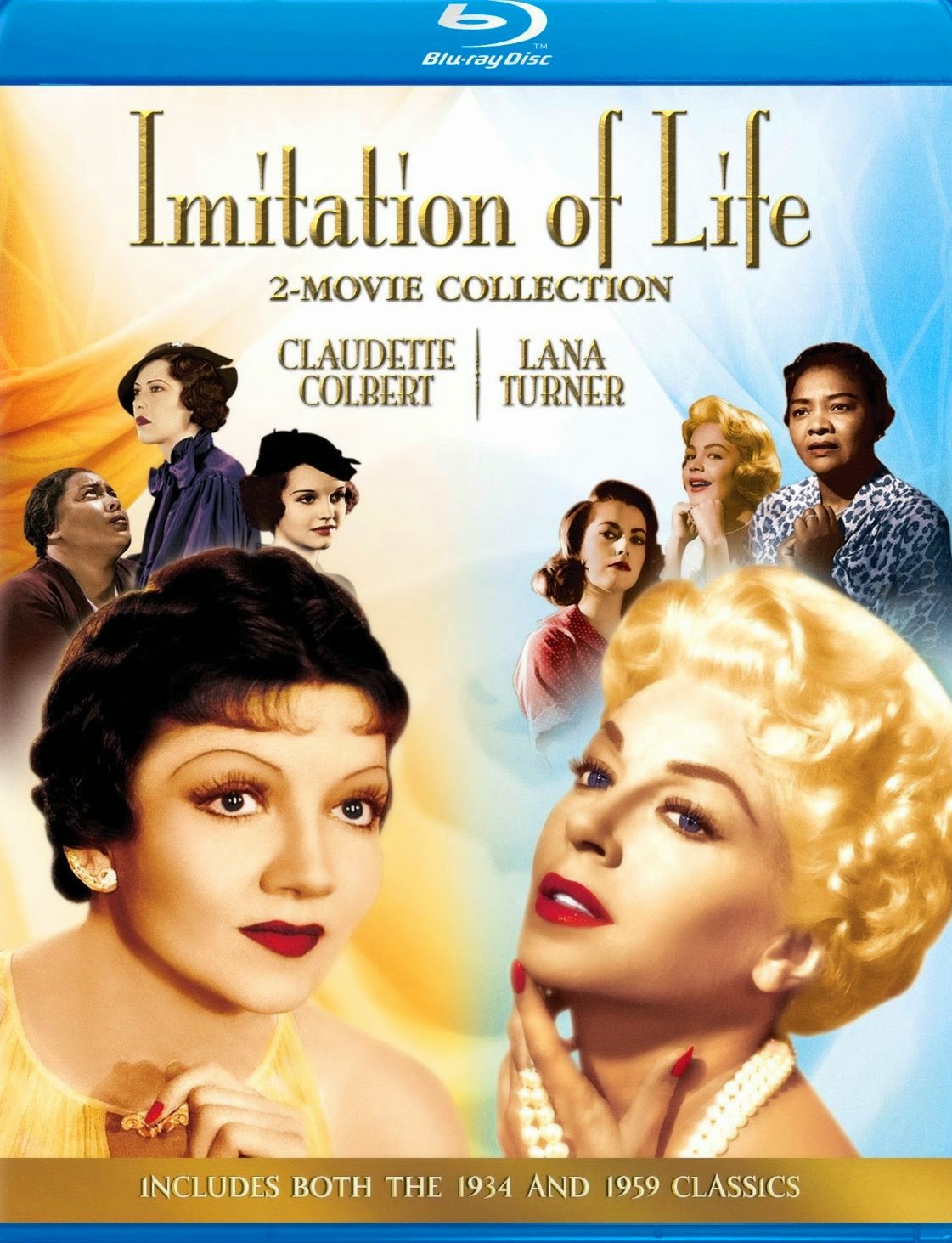

IMITATION OF LIFE: Blu-ray (Universal 1934/1959) Universal Home Video

A mother’s

love, a daughter’s betrayal and the unbroken bond of friendship between women:

by the time director, John M. Stahl’s Imitation

of Life (1934) reached the movie screen it had already garnered minor

controversy among the critics. Its subject matter – a woman of mixed racial

heritage passing for white – was either wholly dismissed or grotesquely misperceived

as subversive satire. Mercilessly, such off the cuff critiques only made the

masses want to see it more. Fueled by the pre-sold popularity of Fannie Hurst’s

1933 novel, Stahl’s ‘Imitation’ was a superb translation

of the author’s unvarnished social critique, made ever so slightly more glamorous

(and thus, more palpable) to the segregationist audiences in the deep South.

Heralding from an affluent Jewish family, Hurst had moved from her native Ohio

to New York to pursue her passion for writing, working menial jobs along the

way and ultimately developing a great sensitivity for the common people’s

plight in modern society. Then, in 1920,

after several years of publishing serialized stories for various prominent New

York magazines, Hurst embarked on an impressive succession of literature:

including 17 novels, plays, screenplays and 8 collections of short stories; as

prolific as she proved dedicated to her craft.

Imitation of Life remains the jewel in Hurst’s

literary crown; made into a movie twice – each time, with overwhelming

commercial success. In retrospect, the

novel is a poignantly penned melodrama. At least part of the novel and the 1933

movie’s popularity is imbedded in the tabloid quality of its taboo subject

matter; miscegenation and the troubled offspring it produces. Hurst, who had been deeply committed to the Harlem

Renaissance, her friendship with Zora Neale Hurston contributing to a better

understanding of racial inequality, had sought to extol the virtues of their

friendship with this sincere homage. It should, however, be noted that Imitation of Life had as many

detractors among the African American community – including Hurston – as it

did within the white power structure. In fact, noted literary critic, Sterling

Allen Brown eviscerated the novel, nicknaming his book/film review, ‘Imitation of Life: Once a Pancake’ in

reference to a line uttered in the 1933 film. In retrospect, Imitation of Life, both as a novel and

two highly successful movies, is a queerly heavy-handed affair; steeped in

stereotypes about sex, class and, decidedly, race relations, more rigidly

ensconced than dispelled. To some extent, Hurst’s weighty approach to all these

aforementioned criteria is somewhat tempered in William Hurlbut’s screenplay,

adapted with an assist from director, Stahl to more prominently feature, then

reigning movie queen, Claudette Colbert.

For Colbert,

the move into more contemporary melodrama was refreshing. She had begun her

career as a DeMille favorite, starring in two of his best remembered trips into

antiquity; 1932’s The Sign of the Cross

(a delicious pre-code Bible-fiction epic in which she appeared in the raw,

bathing in asses’ milk) and 1934’s Cleopatra

(as the smoldering temptress of the Nile); shifting focus into mainstream

dramas and screwball comedies, including her Oscar-winning turn in It Happened One Night (1934), usually

playing saucy vamps or slick women with an agenda. Imitation of Life recasts Colbert as the mother of a teenage

daughter. While playing a parent usually spelled the kiss of death for any

young actress’ career (the movies generally preferring sexy young things as

lovers to housewives) Colbert’s decision to mature her on-screen persona added

yet another layer of respectability to her craft. It also won Colbert the

admiration of her peers as well as her fans and, in retrospect, relaxed

Hollywood’s preconceived notions about, what actress Goldie Hawn would much

later astutely summarize as the three phases of a woman’s acting career: ‘babe, district attorney and ‘Driving Miss

Daisy’.’

The novel is

set in New Jersey, circa 1910 with a lengthy prologue explaining the past of its

central character, Bea Chipley; a mousey girl keeping house for her father and

a male boarder, Benjamin Pullman, whom

she will later marry at her father’s behest. Alas, tragedy strikes twice. Mr.

Chipley is stricken with a debilitating stroke and Pullman is killed in a

terrible train accident shortly before their daughter, Jessie is born. As Bea

is not of an affluent family, her financial situation is immediately

threatened. For a time, she takes in boarders and peddles her late husband’s

syrup door-to-door. A chance encounter with single mother Delilah Johnson, an

African American woman with a ‘light skinned’ daughter of her own, leads to an

unlikely bond of friendship, and later, a business venture profitable for both

ladies. Alas, trouble dogs Delilah’s daughter, Peola; able to pass for white,

but increasingly ashamed of her own African American heritage. Peola breaks her

mother’s heart by severing all ties, marrying a white man in Seattle and moving

to Bolivia where her assimilation as a white woman is never again

questioned. Back in New Jersey, Delilah

dies in despair. Alas, Bea has begun to fall in love with a much younger man –

aptly named, Flake who also takes up with Jessie, now in her late teens. The

last few chapters of the novel are dedicated to this tragic love triangle.

Suffice it to say, it does not end happily ever after for anyone.

Stahl’s

reconstitution of the novel for the 1933 film is not as dire as all that;

particularly forgiving of Bea Pullman (Claudette Colbert) and her daughter,

Jessie (variably played by Juanita Quigley as a toddler, Marilyn Knowlden as

little girl, and finally, as a burgeoning young adult by Rochelle

Hudson). William Hurlbut’s screenplay dispenses with the entire first act of

the novel, also Bea’s first husband and father, instead concentrating on the

warm-hearted friendship blossoming between Bea and her black housekeeper,

Delilah Johnson (Louise Beavers) who also has a daughter, Peola (Sebie

Hendricks as a child, and the sublime Fredi Washington as a young adult). Owing

to concerns raised by Joseph Breen and Hollywood’s self-governing board of film

censorship, Delilah’s earlier marriage to a white European is never mentioned,

although Peola’s ability to pass for white remained a bone of contention for

Joseph Breen.

After

struggling to make ends meet, Bea latches onto an idea to create a pancake

house on the New Jersey boardwalk with Delilah’s help. The place is hardly a hit,

but it causes passerby, Elmer Smith (Ned Sparks) to make the winning suggestion

Bea market her pancake flour, exploiting Delilah as a sort of Aunt Jemima

knockoff and trademark. This proves the kick start to a highly lucrative

business venture for which Bea gratefully offers Delilah twenty-percent of the

residuals. Despite her newfound

prosperity, and either out of loyalty or tradition (the classical Hollywood

machinery particularly adept at seeing African Americans only as suitable

‘hired help’), Delilah remains Bea's factotum. Ten years pass, the matriarchs

united and solidified in both their professional and personal allegiances;

also, in their shared concerns and woes over their daughters. Herein, the old

axiom ‘small children/small problems; big

children/big problems’ will suffice.

Both Peola and

Jessie give their respective matriarchs a run for their money. Jessie is not a

scholar, but rather self-centered and content to rely on her good looks and

charm to get ahead. She is also the first person to refer to Peola as ‘black’

in an unflattering way, thus establishing the impetus for her social dilemma.

At school, Peola does not tell her classmates she is ‘colored’, and is chagrined when Delilah arrives one afternoon to

collect her from class, thus spoiling her secret. Later sent to a ‘Negro

college’, Peola instead drops out, gets a job as a cashier in a prominent

‘white’ store, and increasingly distances herself from her African American

heritage, romantically pursuing young white men who have no idea Delilah is her

mother. When Delilah discovers this, it breaks her heart. Meanwhile, home from

college for the summer break, Jessie develops a naïve school girl’s crush on

her mother’s boyfriend, Stephen Archer (Warren William). Her lust is unrequited, but Bea breaks off

her engagement to Stephen nevertheless, assuring him she ‘may’ return once

Jessie has awakened from her day-dreamy infatuation.

Emotionally

destroyed by her daughter’s betrayal, Delilah suffers a fatal heart attack and

dies with Bea at her bedside. Determined to honor her best friend’s final wish,

to depart this world with a big and splashy New Orleans-styled funeral, Bea

arranges for a grand processional, complete with marching band and horse-drawn

hearse; a repentant and overwrought Peola running alongside her mother’s

casket, begging in vain for her forgiveness.

Presumably, realizing the error of her ways, a tearful Jessie embraces

her mother; Bea poignantly recalling a moment from childhood to realign their

enduring mother/daughter bond, predicated on unconditional love that has not

been broken.

The 1933

version of Imitation of Life, while

taking a few artistic liberties along the way to satisfy the production code,

is nevertheless fairly faithful to Fannie Hurst’s novel; the film’s narrative

structure effectively split roughly down the middle: its’ first half an idyllic

portrait of early family struggles and successes; its latter portion dedicated

to a uniquely American tragedy. In retrospect, what must have seemed

progressive in 1933 now has a decidedly tinny ring of Uncle Tom-ism about it;

particularly a scene where Delilah retreats after a long day’s work as

housemaid inside Bea’s fashionable mansion down a staircase into her own

basement apartment beneath its glittery salons. After all, it was Delilah’s

recipe that made Bea a very wealthy woman, and for which Delilah only receives

20% of the profits, plus a lifetime of servitude as her recompense.

Universal’s

negotiations with the Breen Office were spirited to say the least; Breen

insistent the story’s miscegenation was extremely ‘dangerous from the standpoint of industry and public policy.’

Indeed, early Hollywood sought to expunge sexual relations between the races

not only from its storytelling, but also presumably, as a rewrite of the

historical record by creating its own artificially conceived notion it had

always been a taboo. To satisfy the Code, a scene depicting the near lynching

of a young black man for misreading a white woman’s smile as an invitation to

approach her flirtatiously, was dropped.

Curiously, after 1938, all subsequent reissues of the film also did away

with its title card prologue immediately following the main titles, which reads

thus: “Atlantic City in1919 was not just

a boardwalk, rolling-chairs and expensive hotels where bridal couples spent

their honeymoons. A few blocks from the gaiety of the famous boardwalk,

permanent citizens of the town lived and worked and reared families just like

people in less glamorous cities.”

Imitation of Life was an immediate sensation with

audiences, nominated for three Academy Awards including Best Picture, eclipsed

by that ‘other’ Colbert vehicle, It

Happened One Night – a forgivable loss. Colbert is, in fact, a primary

reason why the 1934 version works so well; also Louise Beavers – two troopers

who elevate the maudlin treacle and sentiment of the piece with a social

conscience. Neither actress is giving ‘a performance’ per say, but reacting

truthfully to the situations and scenes with an almost intuitive inflection,

minus guile or grandstanding. It is saying much for the movie too, that

although rarely revived after 1938, its reputation with audiences endured in

the memory’s eye. Owing to its perennial appeal, director, Douglas Sirk– the

grand master of all movie-land soap operas – elected to remake Imitation of Life in 1959. Alas, Sirk’s version deviates in almost every

regard from both its predecessor and Hurst’s original intent, retaining the

title, but precious little else. And he is doubly hampered herein by having

Lana Turner as his star.

Turner’s post-MGM

career had continued to rely on her wartime status as an elegant pinup and

sweater girl, and, in re-envisioning the role of Lora Meredith (a.k.a. Bea

Pullman) Bill Thomas’ costume budget on the 1959 movie tipped the scales at

over $1 million dollars for Turner’s garments alone; one of the grandest

expense accounts ever in Hollywood history until that time, perhaps not all

that surprising, given Ross Hunter was the film’s producer; a man whose

penchant for resplendent escapism matched Sirk’s own. Although an irrefutable fact of life, Turner

had aged beyond the ‘fresh young fine’

that had once set Metro’s cash registers ringing, she had proven her acting

chops in this interim (most notably, in Mark Robson’s 1957 movie version of Peyton Place). Moreover, and

miraculously in spite of her frequent binges and all-night carousing, Lana was

still a very well preserved thirty-eight years old when principle photography

began on Imitation of Life. But having Turner as its’ star tended to

unbalance the film’s intimate bond between Lorna and her devoted maid, rechristened

as Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore).

In retrospect,

Sirk’s reputation in Hollywood is perhaps one of the most fascinating and

largely untapped stories. In his own time, his melodramas were rarely regarded

as art, despite their overwhelming commercial success. Setting aside Jean-Luc

Godard’s gushing ode to Sirk’s A Time to

Love and a Time to Die (1958), begun with “I am going to write a madly enthusiastic review of Douglas Sirk's

latest film, simply because it set my cheeks afire,” most reviewers readily

pounced on Sirk’s verve for what they misperceived as ‘style’ over ‘substance’.

Indeed, the real renaissance for Sirk’s legacy began nearly eleven years after Imitation of Life’s premiere, with an

article first published in the April issue of Cahiers du cinema in 1967. The

reinvention of Sirk’s reputation in America was begun by Andrew Sarris one year

later. By 1974, Sirk’s contributions on film had been rewritten by the same

critics who had once chastised his efforts, now as having acquired a mantel of

quality, and steadily embraced by a whole new generation of film makers like

Todd Haynes, who would find themselves knee deep in Sirk-land sized glamor.

Aside: apart from its nod to homosexuality, as well as updating the central

romance to contain a very ‘Imitation-esque’ miscegenation scenario, Haynes’ Far From Heaven (2002) is almost a shot for shot remake of Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955) with a

dash of Imitation of Life thrown in.

Still, there

is no getting around the fact Sirk’s conspicuous consumption of all material

signifiers attesting to ‘the good life’ – or, at least, the affluence of upper

middle class morality – is a heavy-handed intruder on Fannie Hurst’s decidedly

intimate tale of the downtrodden makes good; now gussied up in widescreen and

Eastmancolor. Earl Grant’s rendition of Sammy Fain and Paul Francis Webster’s

title song became a jukebox favorite for a time, as did Mahalia Jackson’s

stirring gospel rendition of ‘Trouble of

the World’ – a funeral dirge sung to tear-wringing effect at Annie’s

funeral. And Universal ensured its remake some stellar production values;

second unit location work in New York, most of it used for long shots and/or

process plates to lend an air of authenticity to an otherwise studio-bound

production. Together with screenwriters, Eleanore Griffin and Allan Scott, Sirk’s

updated premise allowed Lora to become a famous actress on her own steam while

Annie assumes the responsibilities to rear Lora’s daughter, Susie (Sandra Dee)

as well as her own, Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner).

In casting Kohner, of Mexican/Czech/Jewish descent, as the movie’s

mulatto, the pivotal plot point of ‘passing’

as another race acquire an unintentionally picaresque quality.

In essence,

Sirk’s remake retained the general framework of the original movie, advancing

to postwar America, circa1947, where widow, Lora Meredith (Lana Turner) is

frantically scouring the beach at Coney Island for any sign of her young

daughter, Susie (Terry Burnham) who has wandered off. Lora pleads with a total

stranger, Steve Archer (John Gavin) to help her look for the girl. Eventually,

Susie is discovered in the care of Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore), a black

single mother with a daughter, Sarah Jane (Karin Dicker) who is about Susie's

age. Lora is so grateful to Annie she

decides to offer them both a room in the back of her cramped New York

apartment. It isn’t much, but Annie is receptive to the notion she can make

something from this new start. Indeed, she makes herself indispensable as a

cook and maid, persuading Lora to stay on so she can pursue her ambitions for a

career on the stage full time. Of

course, this appeals to Lora’s minor streak of narcissism. After some initial

hardships, Lora garners a pair of allies in agent, Alan Loomis (Robert Alda)

and playwright, David Edwards (Dan O'Herlihy). Professionally speaking, it’s

smooth sailing ahead; not so for Lora’s private life. Alas, Steve doesn’t want

her to become a star; shades of the 1950’s sexual stereotypes and politics about

the little woman’s place being in the home effectively woven in.

Herein, Sirk

makes his own minor comment about parental responsibilities too; Lora’s rather

selfish concentration on her career plans causing a deep separation between

mother and daughter, nursed by Annie’s gentle and guiding presence in both

their lives. Too bad what Annie can do

for Susie’s morale she seems unable to satisfy within her own daughter’s

increasing frustrations to ‘pass’ for white. Sirk advances his timeline to

1958. Lora is now the toast of Broadway, living in a luxurious brownstone in

Manhattan. Having hired Annie as her live-in nanny/housekeeper and confidant,

Lora and Annie present a united front against the male-dominated social

structure of their own times. Indeed, Lora has since resisted David’s proposal

of marriage. Professionally, she’s been having second thoughts about his latest

script too. She’s tired of doing light romantic fluff and instead breaks

tradition – as well as David’s heart – by accepting a part in a weighty drama.

The show turns

out to be a big hit. At its after party, Lora is reunited with Steve who has

been absent from her life for more than a decade. But the embers from their

one-time love affair have not entirely cooled. Moreover, Steve is as handsome

as ever; his effect on women not lost on the now teenage Susie (Sandra Dee),

who develops an unhealthy crush on her mother’s boyfriend while Lora is off

shooting a movie in Italy. Meanwhile, Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner) has been seeing

Frankie (Troy Donahue); a hot to trot stud from a socially affluent white family

whom she sincerely hopes will marry her. Tragically, news of her mixed race

heritage precedes one of their clandestine rendezvous and Frankie, enraged by

the notion he has almost become intimate with a black girl, instead brutally

assaults Sarah Jane in a back alley. Sometime later, Sarah Jane gets a job as a

seedy nightclub chanteuse, lying to Annie she is a respectable girl working at

the library. When Annie learns the truth

she marches straight to the club to collect her daughter.

Sarah Jane is

humiliated. But even more debilitating to Annie is her own daughter’s rejection

of her. Thus, when Lora returns from Italy, she discovers a house in turmoil;

Sarah Jane having run away and Annie prostrated in grief. This being the

1950’s, where a woman – even one as independently minded as Lora – can do

nothing on her own, or so it would seem, she instead asks Steve to hire a

private detective to locate Sarah Jane. Time passes, unabated by Annie’s

sorrow. Eventually, word arrives that Sarah Jane is in California, living as a

white woman under an assumed name and having found work as a chorus girl.

Annie’s emotional duress eventually weakens her physical resolve. As worry

translates into depression she summons up all her strength to make the journey

out west to look in on her daughter, wish her well and bid her goodbye. The reunion is hardly a happy one. Sarah Jane

is cruel and nervous anyone should take notice of the dark-skinned woman who

bears no immediate physical resemblance to her. Realizing it was a mistake to

come to California, Annie returns to New York where she suffers a collapse and

becomes bedridden.

Meanwhile,

Susie’s infatuation with Steve grows ominous and critical after she learns Lora

has decided to marry him. Annie breaks the news to Lora from her death bed. Lora

is hurt by the revelation, whereupon a mother/daughter confrontation ensues and

Susie confesses as much. Afterward, Susie realizes what a fool she has been and

elects to go away to a private school in Denver to forget Steve. News of Susie’s departure breaks Annie’s heart

for the last time. After all, she has regarded Susie as much her own child as

Sarah Jane. Unable to recover from this crippling sadness, Annie quietly dies

of a broken heart with Lora at her side. As per her final request, Annie is

afforded an absurdly lavish funeral, Sarah Jane assailing the horse-drawn

hearse and throwing herself across her mother’s casket to beg for forgiveness.

Lora helps the grief-stricken girl into their limousine where Susie and Steve

are already waiting to comfort her as the procession slowly begins to navigate

its way through the crowded, rain-soaked city streets.

The 1959

incarnation of Imitation of Life has

its champions. Strangely enough, I’m torn in my assessment of this movie. It’s

certainly more ostentatious than the 1934 original; infinitely more

over-the-top in its emotional content in place of genuine human emotions and

substance, as only any movie by

Douglas Sirk can be and generally is – at least, on the surface – made ridiculous

by its exotic accoutrements. Luscious Lana remains dressed in the same frock

for no more than a few minutes at a time, never wearing the same outfit twice,

thus putting on a real fashion parade as the quintessence of what’s wrong (or

perhaps right) with the woman’s weepy circa 1959. Evidently, she could never be the dowdy Bea

Pullman as written by Hurst or played with supreme conviction by Claudette

Colbert. But as Lora Meredith she is both a vision and a sight, and something

of an attention whore, scene stealing practically every moment from the more

exquisitely restrained Juanita Moore; except, perhaps, Annie’s death scene.

As it had

happened in 1934, critical reaction to Sirk’s remake was once again split. Most

critics derided it as pure drivel. Interestingly, it has that flaw. But its’

flaw is equally its’ appeal. And the public, for better or worse, generally

speaking – are the arbitrators of what constitutes ‘good taste’ (God help us).

They flocked to see it, making 1959’s remake of Imitation of Life the 9th highest grossing movie of the year with a

whopping $6.4 million intake. For nearly a decade thereafter, this ‘Imitation’

would remain Universal’s biggest money maker of all time, until the release of

1970’s drama/suspense classic, Airport.

Viewed today, Sirk’s remake retains a strangely hypnotic allure; like a car

crash one is privy to but not a part of, it is virtually impossible to turn it

off once the main titles have begun. Melodrama, syrupy or not, is indeed an ‘imitation’ of life; a means for

audiences to live vicariously through the imagined scenarios of a fiction that

often hits too painfully close to home to be virtually ignored or dismissed

outright as mere sentimentalized hogwash.

So, which film

holds up better today? Hmmm. While Claudette Colbert’s performance is bar none

the superior of the two and Stahl’s adherence to Fannie Hurst’s novel in the ’34

version is commendable, the idea of two broke gals getting rich off a pancake

recipe is a little unconvincing by today’s standards. Again, contemporary

opinion ought never be the deciding vote as to what constitutes good solid

entertainment. But Sirk’s glossier treatment has color (no pun intended) and a

lot of kilowatt sparkle to recommend it; also Lana Turner, who looks ravishing

from head to toe. She isn’t Hurst’s heroine – not by a long shot. But she’s all

Lana and, for most this, quite simply, will be enough.

Universal Home

Video has finally come around to reissuing Imitation

of Life on Blu-ray. Both films have been readily available on DVD for many

years; the 1959 version actually issued twice in competing editions, alas,

sporting the same flawed and badly faded transfer. Prepare yourself, then, to

be amazed by what’s here. Despite Universal’s insistence on using the same

cover art as their old DVD ‘book’ release of the two editions as a combo,

everything else about this 1080p Blu-ray is brand spanking new and ‘wow’ do the results speak for

themselves! My one complaint – and, it is an extremely minor one at that – is Universal

has housed both versions on a single Blu-ray disc, instead of utilizing a

higher bit rate by spreading each film across a single disc. What? The whole

$1.95 it must cost to add an extra disc to this packaging was too much for

Universal to splurge on?

But why

quibble when the results are so emphatically a vast improvement over the way

either film has looked on home video before. First, the 1934 edition, sporting

an exceptionally clean and free from age-related artefacts B&W image that

is superbly contrasted and contains a natural patina of film grain looking very

indigenous to its source material. Bravo

and thank you to whoever is responsible for this remastering effort. It’s A-1

all the way, the mono DTS audio also given an upgrade, sounding years younger

with minimal hiss and virtually no pop. Fantastic!

Now, about the

1959 version: as already mentioned, the DVD incarnations herein looked

atrocious with pale and washed out colors, orangey flesh tones and a heavy

patina of grain looking more like digitized grit. The Blu-ray is a quantum leap

ahead in overall quality. There’s really no point to my apples to pomegranates

comparison except to say, double ‘wow’

and triple ‘thank you’ to Universal

for making this reissue a reality. Part of the appeal of the 1959 remake is

Douglas Sirk’s extraordinary use of color to evoke mood. Here, at long last, is

the embodiment of Sirk’s vision brought forth with all the garish va-va-va-voom

one might imagine from Imitation of Life’s

opening night splendor. Not only do colors pop and gleam with an impossible fulsomeness,

but the image is razor-sharp without appearing to have been digitally enhanced.

Film grain that was intrusive and distracting on the DVD has been brought back

into line in hi-def, looking very earthy and spot on accurate. You are going to LOVE this disc. Again, the

DTS mono audio is deftly handled.

Virtually all

the extras contained herein have been ported over from the old double disc DVD release;

including a documentary on the making of both films and two highly informative

audio commentaries; the first, from African-American Cultural Scholar, Avery

Clayton, the other by film historian, Foster Hirsch, plus theatrical trailers for

both movies. We really need to commend Universal for this effort; the best way,

with a flood of orders that will support their efforts and encourage them to do

much more of the same on their, as yet, wellspring of untapped classics in

hi-def. Hey fellas, my vote would be for a new Tammy and the Bachelor, Thoroughly

Modern Millie, and Best Little

Whorehouse in Texas. Okay, I will be silent. Again, and obviously, highly

recommended!

FILM RATING

(out of 5 - 5 being the best)

1934 version 4

1959 version 3.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

1934 version 5+

1959 version 5+

EXTRAS

2.5

Comments