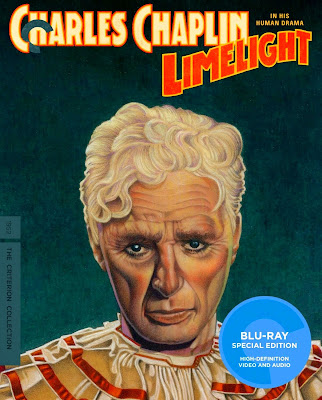

LIMELIGHT: Blu-ray (UA 1952) Criterion

“He was a monument of the cinema, of all

countries and all times ... the most beautiful gift the cinema made to us.”

– Rene Claire

Charlie

Chaplin bid a poetic farewell to his alter ego, the little tramp, in Limelight (1952); the lyrical tale of a

fading comedian, Calvero, who befriends a paralytic ballerina on the brink of

suicide. He instills in her the will to get better and pursue her dreams; she

rekindles a benevolent spark of youthful aspiration in him. Limelight

is more than a poignant love story, thematically touching upon the

elemental grand tragedy of the careworn ‘star

is born’ showbiz ilk. It is Chaplin’s sad adieu to the Vaudevillian

paradiso he knew in the late twenties when his career was just beginning and

the American cinema had first learned to embrace his genius. Alas, by 1950,

Chaplin was persona non grata – and not just in Hollywood; like Calvero, a

legend seemingly past his prime. In hindsight, Limelight is the apogee to Chaplin’s sound pictures; a compendium

of bittersweet emotions and overt sentimentality (for which Chaplin was justly

famous and quite oft’ taken to task by the critics); a picture in which the

peerless master, now sufficiently aged to have seen not only something of the

glories of life but also its unvarnished ugliness, affects his performance with

a very mature outlook, able to regard the tenuous balance between life’s

triumphs and tragedies with clear-eyed precision.

Limelight ought to have marked the pinnacle of Chaplin’s

success in American talkies, except that the picture was pulled from the more

prominent theaters and all but disappeared from public exhibition in America.

For Chaplin had enjoyed his autonomy as a creative genius far too long to suit

a moral/conservative contingent in the U.S. government; had thumbed his nose by

dabbling in political themes with an arguably, naïve and subversive empathy,

and, had had the audacity to marry and divorce three times while continuing to

procure an enviable family lineage – five of his children appearing in Limelight, along with his half-brother,

Wheeler Dryden. To be certain, Limelight is entirely void of any

political themes; an almost autobiographical homage, fraught with a curiously

monochromatic, yet painterly style and tenderness for a way of life, sadly

forgotten. Chaplin had toiled for nearly three years on the story, composing a

sumptuous orchestral score to augment this lovingly hand-crafted portrait.

Owing to the

growing animosity he had incurred in the United States, Chaplin elected to hold

Limelight’s world premiere in his

native England. It seems this decision, and Chaplin’s to refuse taking U.S.

citizenship during his lengthy tenure in Hollywood, brought about a tragic

standoff with Attorney Gen. James P. McGranery, who seized upon the opportunity

to revoke Chaplin’s re-entry permit into the U.S., and furthermore, declared

that if Chaplin dared return he would be subject to a thorough investigation

concerning his political views and moral behavior. Chaplin had, in fact, hinted

he would not be returning to the U.S. anyway. But now, McGranery’s public

chastisement made it virtually impossible for Chaplin to take his lumps in

private. Ensconced in a new home in Switzerland, Chaplin issued his own declaration:

“I have been the object of lies and

vicious propaganda by powerful reactionary groups who, by their influence and

with the aid of America’s yellow press, have created an unhealthy atmosphere in

which liberal-minded individuals can be singled out and persecuted. I find it

virtually impossible to continue my motion picture work, and I have therefore

given up my residence in the United States.”

Publicly,

Chaplin remained austere and introspective about the way things had turned out.

Only those closest to him knew the extent to which this embargo had wounded his

pride. For Chaplin, who had given so much and so freely of himself to this

great nation – particularly in its darkest hours during the Great Depression

and later, WWII, was now vilified as one its’ worst enemies. He would never

again work in the U.S. Indeed, this rift endured, so that when, in 1972, the

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences elected to bestow upon Chaplin an

honorary Oscar for his ‘incalculable

effect in making motion pictures the art form of this century’, the U.S.

State Department begrudgingly issued a forty-eight hour pass for Chaplin to fly

in and collect his award. Those old enough to recall this televised moment, for

which Chaplin received nearly twelve minutes of uninterrupted applause and a

standing ovation from his peers, regard it as one of the sublime triumphs in

the great artist’s career. Limelight,

alas, was not to be discovered by American audiences until nearly twenty years

after its release; the boycott against Chaplin and the movie relaxing with the

more laissez faire changing times.

Limelight is, in many ways, a departure for Chaplin; his

broadly delineated slapstick taking the proverbial backseat to a more restrained

and intelligent melodrama. Like all of Chaplin’s masterworks, Limelight maintains his impeccable

tempo for comic potential; the film’s focus on developing its characters. There

are several ‘skits’ interspersed throughout the narrative; Calvero’s act with a

fellow thespian (played by ole stone face himself, Buster Keaton) to sweeten

the audience’s anticipation for Chaplin in his prime. But now, the tramp’s

quirky mannerisms give way to a more serious demeanor and the solemnity of the

backstory as Calvero’s ‘friendship’ with Terry grows more paternal and then -

even more unlikely - romantic. In Chaplin’s silent classics, his little tramp

was frequently the recipient of unwanted humiliation from a very hostile world.

Herein, the focus shifts slightly to Terry, gingerly coaxed from her

reoccurring bouts of crippling depression by the gentle man, inevitably, no

stranger to hard knocks. What is absent

from Limelight is Chaplin’s

induction of laughter through tears. In fact, almost exclusively he keeps the

two emotions separated or exclusive to particular sequences in the movie. The

tenderness with which he eases Terry from out of her shell and into the

‘limelight’ is marked by tragedy – a main staple of Chaplin’s modus operandi;

Calvero succumbing to a heart attack, knowing he has passed the baton of

performance to a new generation, surely to embrace it with all the love and

passion he once knew and felt as an artist.

Perhaps in

Terry, Chaplin’s aged clown sees something of his former self; sympathetic to

the underdog eager to triumph against seemingly insurmountable odds. Limelight’s aegis is, to be sure,

Chaplin’s tribute to the greasepaint and gaslight era of his parents. Like all his

movies, the narrative is only superficially strung together by a series of

dramatized vignettes interpolated with comedic skits; Chaplin’s unobtrusive

cinema style never allowing the camera to ‘intrude’ on these moments. Rather,

it remains the silent observer with an omnipotent and quiet admiration,

expertly communicated to and lingering with the audience long after the

footlights have come up. Uncharacteristic of Chaplin, the drama in Limelight satisfactorily outweighs the

comedy. Arguably, the picture is far more the byproduct of a ‘mature’ statesman

of life and less the exemplar of that spirited creative zeitgeist who gave us The Gold Rush, The Great Dictator and Modern

Times.

Even so,

Chaplin’s interests in the mise en scene are solely comprised of the camera’s

ability to keep him ever-present in the lens. Interestingly too, Chaplin’s

usual knack for improvisation seems to be lacking in Limelight; one sensing he is adhering closely to his own script

without exploring other avenues along the way. If anything, this leads to a

decided lack of spontaneity. But his evocation of the Edwardian music hall era

remains secondary to his characterizations, another hallmark of his classic film-making

style; his total absorption in the content of the drama at the expense of a

more naturalistic visual appeal. Viewed today, Limelight’s artifice appeals even with these unconvincing and

obvious cardboard and plywood backdrops.

There’s nothing particularly authentic about Chaplin’s London, but

something quite genuine about the people who populate its transparent little

world where the afterglow of limelight is as transient and perishable as the

petals off a blooming flower.

There is

little to deny Limelight as

Chaplin’s most self-conscious and deeply personal movie; set in the beloved and

idealized London of his youth, circa 1914, on the eve of World War I; his aged

has been, Calvero (Charles Chaplin), stumbling up the stoop to his rental

property after yet another night of drowning his sorrows in booze. The movie’s

prolong, delineates limelight as the glamor from which age must pass and youth

enters. But in these opening scenes the scenario is slightly reversed as

Calvero, smelling a whiff of gas from

the hall, bravely breaks down the door leading to the apartment of a young

dancer, Thereza ‘Terry’ Ambrose (Claire Bloom) who has attempted suicide. This

rescue intervention by Calvero and Terry’s doctor (Wheeler Dryden) is

unwelcomed by Terry at first. She inquires, “Why

didn’t you let me die?” to which Calvero astutely rebuts, “What’s your hurry? Billions of years it’s

taken to evolve human consciousness and you want to wipe it out…wipe out the

miracle of human existence – more important than anything in the universe!” These

early moments in what will ultimately become a poignant relationship, are

tinged with Chaplin’s own modesty, his congenial self-deprecating charm,

playing mildly intoxicated, and yet with more than a sincere thread of contempt

for Terry’s inability to grasp the life lesson he is trying to impart.

Nevertheless, Calvero is gentle and self-sacrificing; giving up his bed and

setting up a birth nearby to keep vigilante as she sleeps.

Herein, we cut

away to the first of Chaplin’s ‘skits’ – Calvero’s glorious reign as a supreme

comedian on the Vaudeville circuit; commanding an invisible flea circus. The

audience is reminded of Chaplin in his prime, the inclusion of sound hardly

necessary as Chaplin emotes with great sustained brilliance the follies of

being ringmaster to these miniscule performers, unseen by anyone but his own

perversely serious clown. Back at Calvero’s apartment, the old campaigner

decides to get to know his young charge better. She tells him her parental

lineage – the product of an earl and a kitchen maid; her only living relative,

a sister, Louise, who became a streetwalker in London to pay for Terry’s dance

lessons, then departed in shame to South America. Calvero inquires what made

Terry attempt suicide and she confesses, in addition to her prolonged illness,

it was the utter futility of life; the endless drudge, seemingly without

meaning. “What do you want meaning for?”

Calvero astutely replies, “Life is a

desire, not a meaning.” Later, he further imparts that when all hope

escapes one may choose to live without it and simply thrive in the moment. These

are not flimsy platitudes. For life has not been easy for Calvero either. But

he knows intuitively of what he speaks, referring to the mind as the greatest ‘toy’ ever devised and suggesting from

it the root of all imagination and thus – happiness – can be derived.

We slip in and

out of more vignettes from Calvero’s glory days; the best, a sublime pas deux

between a vagabond and a lady. Calvero confides in Terry that as he grew older

he became more introspective and therefore less capable of seeing the absurdity

in the follies of life; a lethal maturity for a comedian. He lost contact with

his audience and took to drink to console himself. An appointment at the agent, John Redfern’s

(Barry Bernard) offices leaves Calvero hopeful. Alas, Redfern quickly explains

he had finagled a booking at the Middlesex Theater – a middling venue where

Calvero is not even to get star billing. Redfern makes it clear Calvero’s is an

anathema to the theater’s management. They have agreed to sign him, but only as

a huge favor to Redfern, who has been talking him up for many weeks and, unlike

Calvero, has maintained enough of a cache in the business to persuade, despite

their reservations. Returning to his apartment, Calvero learns from the doctor

that Terry’s paralysis is psychosomatic. Physically, there is nothing wrong

with her legs. So, Calvero attempts to break Terry of her imaginary illness;

his pop-psychiatry explaining to her it is human nature to despise ourselves.

Herein,

Chaplin shifts the focus of the narrative to a flashback told by Terry; her

first fleeting glimpse of romance with a shy American composer, Neville (Sydney

Chaplin) whom she mildly worshiped from afar; nightly, stalking his flat to

listen through the door to his compositions and deliberately favoring his

purchases of sheet music at her store with extras or returning to him

unnecessary change. Terry’s boss eventually catches on to her infatuation and

discharges her for stealing from the till. She briefly returns to her first

love – dancing – but succumbs to rheumatic fever. Five months after her

recovery, Terry sees her young love again at the Albert Hall. Calvero wisely

assesses that although the two have barely met, she is desperately in love with

this young man. Calvero paints a rather prosaic picture of how Terry’s romance

will end; with a flourish of violins, hearts and flowers – a glorious summer

romance over flickering candlelight, with the city dreamily backlit for their

enduring affair. Mrs. Alsop (Majorie Bennett) urges Calvero to pay up his rent,

also to get rid of Terry from his apartment to avoid rumors, suggesting there

is something spurious about the relationship between this ingénue and old man.

Calvero responds with a playful romantic overture to Mrs. Alsop. She isn’t

fooled for a moment, but is decidedly

distracted; her heart somewhat softening, though not by much.

Upstairs,

Terry learns Calvero’s contract with the Middlesex has been terminated. With no

money coming in to sustain them, Terry gets a job as a chorus girl in Mr.

Bodalink’s (Norman Lloyd) Arabian nights’ fantasy musical revue. Her diligence

earns her Bodalink’s respect. She finagles an audition for Calvero and Bodalink

enthusiastically offers to help the old clown win back a modicum of his

self-respect. The show’s backer, Mr. Postant (Nigel Bruce) is unimpressed, but

the show is a great success. Better still, Terry is reunited with Neville who

has been hired to compose the music for their new show. The two rekindle their

platonic love. Terry, however, is torn in her allegiances. Calvero is wounded

too, but only at the thought of losing the girl who has come to mean a great

deal to him. However, he understands too well nature must pull in the

inevitable direction of true love. Besides, it’s no good. Terry is young. She

ought to be with her young man. Calvero tells her so after she suggests the two

give up the theater and retire somewhere to a cottage or little farm in the

country. Terry and Calvero come to a parting of the ways and Terry embarks on

her own career.

The war

intrudes and Neville enlists. Calvero takes up a job as a minstrel in a seedy

little pub where he is reunited with Neville, who is on leave from the army.

Shocked to find Calvero has sunken to this level, Mr. Postant suggests Calvero

see him about a part in his new show. Calvero is, instead, cordially glib,

refusing to even entertain the notion. But a short while later Terry inadvertently

sees Calvero on his way back to work. She rushes to his side and encourages him

to audition for Postant’s revue. Calvero is reunited with his old partner

(Buster Keaton); the two preparing to revive one of their time-honored comedy

routines. Terry confides in Postant she intends to marry Calvero, to make him

happy and return to him the great favor and gift for living that he has

bestowed upon her. Alas, this is not to be. For Calvero, having completed his

act and brought down the house no less, suffers a fatal heart attack. He is

carried to the wings of the theater as Terry takes to the stage. As she

pirouettes magnificently about the proscenium, the doctor is summoned to

Calvero’s side; pronouncing him dead with Neville, Postant and Bodalink

mourning the loss, but Terry – as yet – unaware her beloved mentor and friend

has gone.

In retrospect,

Limelight is undoubtedly Chaplin’s

last great work; perhaps not his greatest, yet undeniably his most personal and

heartfelt: an extraordinary achievement for the old master, and at an age when

most artists are winding down their careers. Chaplin had labored on the script

for decades, going through rewrites and re-conceptualizations until he tweaked

the particulars to his complete satisfaction. The picture was shot in just

fifty-five days, a record for Chaplin who, in his prime, had been known to toil

for months, improvising his performance as he went along, discarding scenes

already shot, reshooting others, and still, working brand new ideas and

routines into the project; all in his ceaseless effort to achieve the perfection

in his mind’s eye. Alas, by 1950, such embellishments were impossible, even

under the freedoms of his own studio; the skyrocketing cost of making movies putting

a period to this sort of experimentation. Nevertheless, what Chaplin lacked in

shooting schedule he made up for in his prep time; Limelight evolving in the back of his mind while he pursued and

created other projects.

The picture is

entirely shot in Hollywood, mostly at the Chaplin Studios, with exceptions made

for the exterior street scenes, redressed sets already built at Paramount

Studios, and the music hall sequences, filmed at RKO. To add authenticity to

the exercise, Chaplin also used existing footage of actual London locations rear-projected.

At the time, many critics assumed Calvero was Chaplin’s alter ego for his

father who, like Chaplin’s fictional creation, had suffered a similar fate and

turned to alcohol for solace. Interesting too, are the parallels between

Chaplin himself and Calvero; both men’s professional careers in their twilight

rather than their prime. However, a pair of biographies written by Chaplin

suggests the character was loosely based on the life of stage actor, Frank

Tierney.

Limelight is, of course, historic for its pairing of Chaplin and

Buster Keaton. During the silent era, these two had been the titans of comedy.

In the interim, Keaton’s path had taken a different turn; the introduction of

sound leading to his inevitable eclipse from the movies; infrequently

resurfacing in bit parts – a very sad adieu to his reign as the comedic genius

and silent star of the first magnitude. Chaplin had, at first, resisted casting

Keaton, believing the role too small. However, upon learning Keaton had suffered

financial hardships due to his disastrous divorce Chaplin adamantly insisted he

be cast in Limelight. Furthermore,

it appears the enduring rumors about Chaplin jealously hacking into Keaton’s

performance to diminish its impact are little more than simply that: rumors

begun by Keaton’s business partner, Raymond Rohauer. As for Keaton, according to his widow,

Eleanor, he was simply thrilled to be working with Chaplin, finding his

contemporary congenial to a fault. Chaplin allowed Keaton to explore his

performance at his leisure and experiment on the set. Chaplin, in fact, trimmed

portions of his own performance to allow Keaton his moment in the spotlight.

Based on his

own novella, Footlights, Limelight is likely a derivative of

Chaplin’s personal reflections on his career. Yet, it is utterly void of any

and all showbiz stereotypes and clichés, possessing a unique flavor and

infectiously sincere quality. As a symbolic characterization, Calvero is Chaplin under siege; threatened by lawsuits

and politicized witch hunts; the American premiere of Limelight picketed by those believing the rumors about Chaplin

being a communist. How quickly the mighty had fallen. Only a decade earlier,

Chaplin was regarded as one of the supreme entertainers of his time.

Mercifully, time has not diminished Chaplin’s reputation. If anything, removed

from all the hate-mongering, Chaplin’s resiliency, as well as that of his

‘little tramp’ have come around to be more perfectly ensconced as imperishable

symbols of the American motion picture, despite changing times, tastes and

virtues.

Limelight remains that wistful portrait painted in light by a

genius whose command of his craft, his understanding of humanity and its fatal

flaws, and his passion for both the theater and the art of making movies are

peerless and impeccable. Clearly, Chaplin has drawn his inspiration from a

purposeful life; bottling the essence of an aging artiste, young enough in his

mind to recall the comedy of life, but as experienced by its pitfalls and

tragedy. The tenuous balancing act Chaplin achieves between these polar

opposites remains the film’s coup de grâce: an ingeniously interwoven tapestry.

Chaplin’s supreme virtuosity, as a

philosophical student of life, ensures

Limelight never becomes overly introspective or maudlin. When

sentimentality is employed it is with the innate understanding nothing more is

required of the moment than a good cry. And yet, the results never seem deliberate

or out of place. For perhaps the only time in his career, Chaplin allows the

drama of the piece to unfold around both his alter ego and his female star, the

movie’s narrative structure creating concentric ripples from a central hub.

Calvero’s final request, to have his couch carried into the wings of the theater

where he can witness the fruits of his labors brought to full flourish – Terry’s

balletic triumph – remain the hallmark of Chaplin’s own artistic creed. If

there must be finality to all great endeavors, then let it come with a grace

and dignity befitting the glorious wonders of living that life to its fullest.

Criterion’s new

4K Blu-ray is magnificent. Let’s be honest; the old Mk2/Warner release on DVD

was an abomination; interlaced and riddled in edge effects that made the movie

virtually unwatchable. Overall, the quality herein will not disappoint. The

image has been stabilized and texture, grain and contrast all rank as superior

over the aforementioned SD. Fine detail

in close-ups is startling. Grain is heavy but looking very indigenous to its

source. Clarity and depth is exceptional

during brightly lit sequences and shadow definition is extremely solid, with

nuanced blacks and grays. Criterion’s remastered LPCM mono audio will not

stretch the breadth of your surround system, but it is more than competently

rendered and supports the movie’s dialogue-driven narrative with renewed

clarity. No hiss or pop. Chaplin’s score sounds sublime and is utterly free of

distortion.

Criterion’s

extras are formidable and most welcome; beginning with David Robinson’s

formidable video essay: Chaplin’s Limelight – Its Evolution and

Intimacy. Here, at last is a

fitting tribute to the movie as well as Chaplin’s penultimate act in showbiz.

We also get new interviews with Claire Bloom and Norman Lloyd, each offering

astute recollections of what it was like to be a part of this classic and share

in Chaplin’s extraordinary gifts. Criterion has also graciously included Mk2’s

2002 featurette, ‘Chaplin Today: Limelight’ – a superficial summarization of the

movie and its enduring appeal; plus two of Chaplin’s shorts: A

Night in the Show (1915), and, the never completed The Professor (1919). The

former has been lovingly restored by Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna and Lobster

Films from a polyester fine grain preserved with miraculous results at The

Museum of Modern Art and presented herein in full1080p with Dolby Digital 2.0

audio. The latter is in very rough shape, exhibiting varying tonality and some

horrendous age-related damage, presented herein in 1080i and mono. Finally, we

get Chaplin reading excerpts from ‘Footlights’,

some brief outtakes from Limelight,

and two theatrical trailers. Criterion also includes a spectacular booklet with

essays from Peter von Bagh and journalist, Henry Gris. Bottom line: very highly

recommended!

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

5+

VIDEO/AUDIO

4.5

EXTRAS

5+

Comments