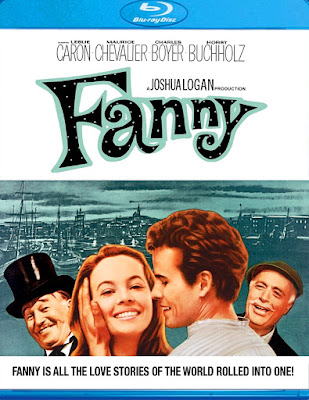

FANNY: Blu-ray (Warner Bros. 1961) Shout! Factory

The greatest

of all movie romances mirror the analogous trajectory of the complex and

inconspicuous frailties of life: he said

that he loved her. She said that she loved him. Then they both decided to go

their separate ways. Such is the incongruity and fitfulness of being human;

to love and be wounded in love/by love; to suffer discontentment and

disillusionment within the resolve of life’s struggle, if only to periodically

unearth nuggets of truth, wisdom, and on that rarest of occasions, satisfaction

in the choices made. Magically photographed on location by one of the irrefutable

masters of cinema, Jack Cardiff and directed with a bittersweet, yet zestful

flavor for the port city of Marseilles; Joshua Logan’s Fanny (1961) remains a lithe, yet amazingly candid and

perspicacious champagne cocktail about the intangibleness in sustaining the pleasures of

life, and, the grave sacrifices one makes along its journey to the inevitable. At

intervals, Fanny is joyously yet utterly heartbreaking; a tearful, lyrical, and engrossing amalgam of art

imitating the all too human foibles. If roses are the unofficial representative

of an idyllic affaire de Coeur movies of Fanny’s

vintage oft aspire to, then dandelions mark a distinct reminder: no love worth having is an

Eden without weeds.

Consolidating

and highly romanticizing plot points from the first two installments in French

playwright, Marcel Pagnol’s affecting ‘Marseilles Trilogy’, the Broadway

musical adaptation of Fanny (the

second play in that trilogy) had its debut in 1954 and was an immediate

success. Interestingly, while the first two Pagnol plays, Marius (1929) and Fanny

(1931) were designed for the theater, the final installment, César (1936) first came into being as a

movie (directed by Pagnol); ten years later to follow its predecessors as

successful stagecraft. Fanny had, in

fact been translated into a movie back in 1932; director, Marc Allégret’s

poetic adaptation still considered a classic of the pre-war French cinema.

Logan’s 1961 reincarnation thus faced two hurdles; the enduring reputation of

the ’32 version and, audiences more recent expectations the new movie would

teem forth with Harold Rome’s lush Broadway orchestrations and songs. Two

things prevented the inevitable: first, Jack L. Warner’s outright purchase of

the property in 1957; wary of the recent decline in big screen musicals’

popularity. Interestingly, Warner would reevaluate this decision to abstain

after UA’s 1961’s West Side Story

proved a colossal smash hit, Warner going on to produce several noteworthy

musicals throughout the decade, including The

Music Man (1962), and, My Fair Lady

(1964). The second decision to impact Fanny

was Warner’s choice of screenwriter, Julius J. Epstein who, along with his

brother, Philip had written some of the studio’s most iconic hits of the

forties; Casablanca (1942) and Mr. Skeffington (1944) among them.

Epstein had virtually zero interest in adapting a musical. He did, however,

possess a passion for Pagnol’s original works, though interestingly, kept the

ending from the Broadway musical (which deviates considerably) to conclude his

filmic adaptation.

Leaving all

the memorable songs on the cutting room floor nevertheless proved something of

a blessing in disguise as practically none of the cast eventually assembled for

the picture had any prior experience in musicals; Rome’s orchestrations – minus

their lyrics – used as underscore. Part

of the picture’s success is owed to its impeccable casting; the grand

boulevardier, Maurice Chevalier (the only musically inclined performer to

appear in Fanny) as wealthy

widower/ship merchant, Panisse; Charles Boyer (who had originally refused the

role when it was first anticipated he might have to sing – a talent Boyer

lacked), as the incomparably compassionate, César; Horst Buchholtz - his son,

Marius and, as the title heroine, the winsome Leslie Caron (in a part

originally intended for Audrey Hepburn). In the play Fanny and Marius are still

teenagers; eighteen and nineteen respectively, while in reality Buchholtz was

twenty-eight and Caron thirty. There are others in the cast who lend an air of

authenticity to their memorable cameos; Georgette Anys as Fanny’s mother/portly

fishmonger, Honorine; Raymond Bussieres as the somewhat detrimental enabler,

The Admiral; Victor Francen, who as Panisse’s elder brother, delivers an

eloquent soliloquy of ‘thanks’ to the new mother for perpetuating their family

name (apparently all of the Panisse men from this previous generation were born

sterile), and, Joel Flateau who, in what could so easily have devolved into a thankless

part as Césario, the illegitimate offspring of Fanny and Marius’ one-night

flagrante delicto, is given Panisse’s good name and his formidable kindness and

resources; the child star nevertheless establishes a memorably angelic presence

to makes us care about Césario’s past as well as his future.

Fanny is a poignant and oddly glamorous affair, Jack

Cardiff’s vibrant cinematography transforming the fishing port of Marseilles

into an elegant seaside retreat. Beginning with the picture’s dizzying descent

from the clouds into the city’s bustling harbor – a miraculous and daring

helicopter shot that introduces us this eclectic, vital and colorful anchorage,

to the elegantly moonlit water’s edge where Fanny crystalizes her deep-seeded

passions to and for the somewhat obtuse Marius; Cardiff’s visuals ply a luminous

patina to these sun-baked and cobblestone byways, intimate enclaves crowded with

the rawness of people who love, sin and falter on the altar of their best

intentions, yet somehow manage to make not only the best out of an increasingly

awkward situation, but come together to attain at least a smattering of their

more altruistic pursuits. Fanny is a

perfect parable for an imperfect love and an even less intact reality, created,

then endured by its titled protagonist; driven to possess a young man, too

immaturely full of his own passions to ‘be someone’ and not entirely convinced

love of a good woman alone is enough to sustain his dreams. Too late, he

discovers the error in this adventurist’s spirit; choosing a life at sea while

quite unaware his one night of farewell passion has resulted in a pregnancy.

The situation

is further complicated by Panisse; impotent and far too old to squire the fires

of lust in Fanny’s heart, yet perhaps able to provide the girl with an out from

her predicament; a marriage of convenience in which her child will be reared as

his own. The town, including Marius’ father, Fanny’s mother and the entire elder

Panisse clan, band together in celebration of the child’s birth; only some to

maintain the secret and their own respectability while others continue to know

absolutely nothing about the ‘arrangement’; the wrinkle in their carefully

orchestrated ruse – Marius – who returns after only one year abroad to discover

Fanny has married and produced a child he later learns is his own. As the boy

matures he looks more like his father and is drawn to the people and places

Marius once adored; a bitter pill for Panisse to swallow, and yet, ever so

pragmatically understood within the natural order of life renewing itself. On

the eve of a planned ‘circus/party’ for Cesario, Panisse is fatally stricken

with a heart attack. As Fanny has come to love Panisse, if only for the forfeits

made on her behalf, Panisse quietly asks César to preside over Fanny’s second

marriage to Marius and the gentle rearing of the child he has come to regard as

his own, who all agree must never know the truth of his parentage. Herein, the

picture is exceedingly and most uncharacteristically guileless; everyone

pulling in service of the boy, but also, to honor Panisse’s memory, without

whom none of Cesario’s now promising future would have been possible.

After the

initial descent into the harbor, Fanny

begins with a routine charter crossings of local ferryboat captain, Escartifique

(Baccaloni), whom we learn is prone to seasickness. We are also introduced to

The Admiral, a somewhat ‘crazy’ town bum whom we later learn was prevented in

his youth by an overweening mother from pursuing his love of the sea. The

parallel is thus made early on: that if Marius, equally driven by an innate

desire to sail away from Marseilles, is forced to remain in service to his

father, he will surely suffer a similarly cruel fate. César, the local barkeeper

is devoted, but equally as blind to his nineteen year old son’s thirst for

adventure. He is more keenly hopeful Marius will inherit his establishment

after he is gone; in the meantime, marrying Fanny, the daughter of a seaside

fishmonger. Fanny’s mother, Honorine is in hot pursuit of Panisse, an elder

merchant with a respectable business. Despite his advanced years, Panisse is

the most eligible catch in the county. The wrinkle here is Panisse would much

prefer Fanny, who is at least thirty years his junior. Panisse, Cesar and

Escartifique, along with a resident Englishman, Monsieur Brun (Lionel Jeffries)

are fond of playing a rather sadistically ridiculous game; placing a heavy rock

beneath a brim bowler left in the street and waiting for unsuspecting passersby

to kick it. However, the trick backfires when the local clergy partakes of this

opportunity and wounds his foot as a result. In these opening scenes, Joshua

Logan simultaneously establishes the essence of time and place with an impeccably

erudite sense of the cinema space and a genuine flair for the people who call

Marseilles home. There is a lazy cadence to life in this port city, a sort of timeless

‘matter-of-fact’ most everyone except Marius accepts. Prompted by The Admiral’s

vicariousness, Marius’ head has been cluttered in daydreams of sailing around

the world. Secretly, Marius has already packed his tote; the Admiral arranging

for the sailors of a rare scientific sailing expedition presently docked in

port to take Marius on as their first mate.

Unable to tell

his father the truth, Marius instead makes a rather feeble attempt to explain his

love and gratitude to Cesar. This is heartily reciprocated. Cesar is very proud of his boy; a pride soon

to be tested as Fanny lures Marius to the docks to confess her undying love for

him. She has worshipped Marius ever since they were children and cannot imagine

a life without him. Overwhelmed by passion, Marius allows himself a night’s

indiscretion with Fanny; the young couple discovered at dawn by Honorine who

has unexpectedly come home early from her out-of-town trip. Deeply

disappointed, Honorine confides her discovery to Cesar, who is less appalled

and more generally hopeful by this turn of events. For certain, Marius must now

settle down, marry Fanny and assume responsibility for their lives together: a

perfect arrangement, as far is Cesar is concerned: except Marius still intends

to sail away with Fanny’s bittersweet complicity. Fanny helps lure Cesar away

from the boat’s launch while Marius hurries aboard, spied in his departure by

Panisse who is both confused yet quietly elated to have his competition for

Fanny’s affections leave Marseilles, presumably for a five year expedition at

sea.

Some two

months later, Fanny realizes she is pregnant with Marius’ child. Upon learning

of the child, Honorine violently beats her daughter for the shame she has

brought upon their household, but then repents for this hasty anger by begging

for Fanny’s forgiveness. Still, it will mean ruin and exile for them both as

the pious town gossips will not tolerate an illegitimate in their midst.

Honorine now hatches a plot. Fanny should marry Panisse. Indeed, Panisse has not

waned in his pursuit of her since Marius’ departure. But Fanny is incapable of

fooling Panisse. Instead, she confides in him the error of her ways. He is

moved and very understanding; much more so than Cesar who, at first, is

outraged the girl that ought to have been his daughter-in-law, has agreed to

marry an old man, thus depriving him of his grandson. Panisse smooths over this

insult by allowing Cesar to be the unborn child’s godfather. The plans settled,

Panisse and Fanny are married; a most ‘unhappy’ affair for Fanny who, even as

the blushing bride in white on her wedding day, cannot rid herself of Marius’

memory. Upon young Cesario’s birth, the extended Panisse clan descends upon the

house; Panisse’s elder brother offering a genuinely heartfelt thanks to his

dear sister-in-law for propagating the family lineage that otherwise would have

died out with their generation.

For a while,

all is well and pleasant; Panisse and Fanny rearing Cesario according the

agreement. Alas, on the eve of the child’s first birthday, Panisse is called

away on business to Paris, and, as fate would have it, Marius returns from his

travels abroad. Too late, Marius learns from Cesar of Fanny’s marriage and

‘their’ child; Cesar refusing to tell his son the truth about the boy’s

parentage. Hurrying to Panisse’s home, Marius feigns having come to bestow his

blessings, but soon confesses his spirit of adventure has cooled. He realizes

now what a fool he has been for giving up Fanny. The rude awakenings continue

as Marius learns the child Panisse is rearing is not his own. Cesar intrudes

upon the couple’s flawed intent to rekindle their affair, discouraging it as

tasteless and cruel, especially since Panisse has missed his train and is certain

to return home. Panisse arrives and is confronted by Marius who is bitter and hurt,

yet conflicted in his gratitude for the kindnesses Panisse has shown the child

he unknowingly abandoned. Panisse informs Fanny that if she would prefer, she

may divorce him now to wed Marius. But the child will remain his to rear as his

own. Cesar agrees, telling Marius, “You

were his father before he was born. But Panisse has been ‘a father’ to the boy

ever since.” Bitterly acknowledging Fanny will never abandon their child

for him, Marius departs Marseilles again…or so it would seem. Actually, he has

merely exiled himself to Toulon, working as a mechanic while making even more

ambitious plans to immigrate to America and begin anew.

Time passes,

but it does not heal all wounds. Marius grows more resentful and distant. To

prevent the child from ever coming in contact with his past, Panisse moves his

family away to a manor house on a hillside overlooking Marseilles. Honorine’s

birthday gift of a telescope brings the port closer to the child’s heart.

Indeed, Cesario is inexplicably drawn to ships and adventure, just like his

real father. As Panisse is planning a circus/party for the boy’s birthday,

Cesario learns about Cesar’s son, Marius. Panisse asks Honorine to take Marius

to the park to distract him while the circus performers set up their wares in

his front yard. Instead, Honorine decides to take the boy to the wharf where

she once sold fish. Reunited with two of her old sellers, Honorine loses sight

of Cesario for a moment. He meets The Admiral who recognizes the boy as Marius’

and takes him to meet his real father, now working as a mechanic on the other

side of the city. Meanwhile, Honorine frantically returns to the house,

informing Panisse and Fanny she has lost Cesario. Panisse, who has been in

declining health for several years, suffers a heart attack. But Fanny, wisely

deduces what has become of her child and charters a boat. She finds Cesario and

Marius together, informing her son ‘his

father’ is gravely ill. Marius offers to drive them back home – a faster

route that Fanny gratefully takes advantage.

Spying their arrival from his bedside, Panisse asks Cesar to take down a

letter. He is dying and wishes that after he is gone his estate will go to

Fanny and Cesario, with the added codicil Fanny may marry Marius and thus

ensure the child is restored to the father he has never known. Tearfully, Fanny

confesses to Panisse she has grown to love him over time; for he has been

exceedingly good and kind-hearted as both provider and husband. The movie

concludes with Marius and his son bouncing on a trampoline in the forecourt of

Panisse’s home; the family restored – perhaps.

Fanny is a movie imbued with two parts, a certain je ne

sais quoi, to one part, immeasurable joie de vivre; immaculately

counterbalanced by a nostalgic sense of humor for a way of life now all but

dead and forgotten. Joshua Logan’s personally supervised production is owed

considerable accolades for transforming Pagnol’s modest Marseilles Trilogy into

a strikingly pictorial epic devoted to love: imperfect, alive, sincere,

fragile, and yet, noteworthy in all its flawed tenacity and believability. Fanny is a beautifully told and

remarkably true-to-life romantic ‘fable.’ Borrowing the best from Pagnol’s

original and the Broadway spectacle concocted by S.N. Behrman and Joshua Logan,

screenwriter, Julius Epstein has transferred these textual sentiments into a

coherent and lissome confection. Fair enough, there are some flaws in the

overall construction; the early scenes a tad too rushed, the penultimate

grandeur of the Panisses at home rather absurdly realized. After all, Honore

Panisse is a seller of sails and other nautical gear; not an industrialist

whose money could have afforded such a lavish estate as depicted in the movie.

And, at times, the cultured finesse that quite simply is Maurice Chevalier seems insincerely at odds with the more modest

merchant he is playing; a sort of Honoré LaChailles from Gigi (1958) gone ever so slightly to seed or not altogether

successfully disguised. But on the whole, Joshua Logan and his cast have pulled

out all the stops for a delicately balanced, effervescent and utterly charming

‘love story’; peerless, pleasing and with exceptionally few contenders to

rival its moody magnificence. While

Harold Rome’s lush underscore occasionally draws more direct reminders to the

Broadway musical, and the loss of the songs that made the stage’s Fanny such a memorable ‘show’; Logan’s

substitution of somewhat sentimentalized tragedy is more than serviceable. In the end, Fanny is tasteful, affecting, lovely and charming to a fault.

We cannot say

the same about Shout! Factory’s abysmally second-rate Blu-ray release. To

preface, Fanny has never looked good

on home video. But this Blu-ray only seems to exaggerate the inherent flaws

built into this careworn print while minimizing its pluses. For starters, the

opening credits are window-boxed in 1.66:1 while the rest of the feature is

presented in 1.85:1. Never having seen Fanny

theatrically, I still cannot imagine this was ever Joshua Logan’s intent,

although the credits nevertheless appear comfortably fitted within this cropped

image. Worse are the egregious age-related artifacts scattered throughout this

transfer, but obtrusively distracting during the main titles, all but ruining Jack

Cardiff’s sublime descent from the clouds into the port city of Marseilles. The

title featuring Cardiff’s screen credit is so muddy, dull and poorly

contrasted, it is a slap in the face to his keen camera eye. While overall

quality greatly improves once the opticals have ended, the image never reaches

the lushness of a vintage Technicolor transfer; flesh tones wan instead of

sun burnt, and reds generally leaning towards a garish orange.

With

intermittent examples to the contrary, the overall color palette is faded and

contrast is weaker than anticipated.

Detail in close-ups is pleasing, but in long shot tends to look slightly

blurry and soft. This really is not the

way Fanny ought to be seen and it is

a genuine shame Warner Bros. never bothered to renew the rights to a picture

they helped to produce, since having fallen into public domain and looking

every inch the travesty befallen most PD titles. Nothing short of a full-blown

chemical and digital restoration will suffice at this point, though it remains

highly unlikely Fanny will ever

receive such a five star treatment. Pity that! The audio is DTS mono and

adequate, but only just; dialogue sounding crisp; the score lacking bass

tonality. Save a theatrical trailer, there are NO extras. What a shame and a

sham. Even the old – and now retired ‘Image Entertainment’ DVD gave us a

separate disc containing the movie’s ‘soundtrack’. Shout! could have done as much

as an ‘isolate score’ option. But no and how sad. Fanny

is a movie deserving of our love. But this Blu-ray is a Frisbee and not worth

your time or your money. Pass and be very glad that you did!

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

4.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

2

EXTRAS

0

Comments