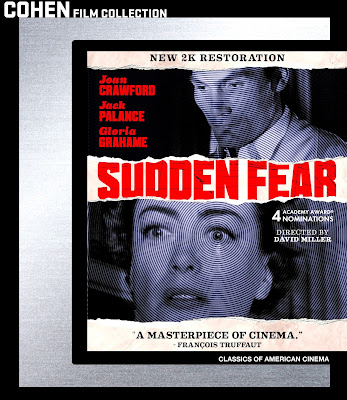

SUDDEN FEAR: Blu-ray (RKO Pictures 1952) Cohen Media Group

Since

Shakespeare’s time, the honored tradition teetering on cliché has been ‘hell hath no fury like a woman scorned’.

But I sincerely think a case can be made in David Miller’s sublime and

occasionally overwrought thriller, Sudden

Fear (1952) for the male of our species to suffer from a similar

affliction. In Sudden Fear we have

not only a clear cut case of the homme fatale interceding on hallowed ground

usually ascribed to the ‘femme’ (in

this case, one of Hollywood’s heavy-hitting power brokers, Joan Crawford), but

also a blood-curdling powerhouse of a performance from both Crawford and

co-star, Jack Palance; each looking quite angular, haunted and spooky to

downright horrifyingly unattractive. Curious to say what Crawford’s

accomplished playwright and heiress, Myra Hudson sees in Palance’s Lester

Blaine; the actor she fires from her latest stage hit, Halfway to Heaven, while the play is still in rehearsals – not,

because he gives an incompetent reading of her work (au contraire, it is the

most passionate reading of an intense love scene to impress both the play’s

director, Bill – Lewis Martin, producer, Scott Martindale - Taylor Holmes and

Myra’s doting secretary Ann Taylor - Virginia Huston) but rather because he

lacks what Myra envisions as raw animal magnetism capable of making her female

audience instantly swoon. Given the bad news by Bill, Lester confronts Myra

with the physical particulars of that most legendary of lovers - Casanova; who

suffered a crooked jaw, birthmark just above his chin, Dumbo-sized ears and a

heavy scar near his left brow. Lester’s point is well taken. Sex appeal is in the

mind and exuded by presence and character, as a good many of the legendary male

stars from Hollywood’s golden era, considered ‘hunks’ in their day, have

occasionally lagged in the physical department, yet nevertheless managed

enduring careers as leading men and/or perennially sought after ‘love interests’.

For many, Jack

Palance never quite attains this level of desirability however, and yet there

is something rather fascinating about him; a rare and intangible quality

emanating off the screen as it simultaneously burrows into Myra’s fickle heart

as she first empathizes with his wounded rejection; then, even more uncannily,

begins to harbor more deep-seeded amorous aims during their New York to San

Francisco train trip. And Crawford, after embodying the house style of at least

two studios in her ever-reinvented career (first, at alma mater, MGM, chiefly responsible

for rescuing a little known Charlston cup-winning flapper named Lucille LeSeur

from the chorus and transforming her through their glamour gristmill into the

presence we think of today as Joan Crawford) then, at Warner Bros. (where

Crawofrd usurped grand dame Bette Davis’ screen supremacy) that studio,

reshaping and tweaking Crawford’s persona to fit their ‘ripped from the

headlines’ star quality in uncompromising and gutsy drama queens; Crawford was by

1952 her own free agent, though arguably not by choice (well…sort’a) under

agent, Lew Wasserman’s inspired tutelage. I suspect Crawford would have

preferred to remain either at MGM or Warner Bros. for the duration of her fame –

if only these studios had not already tired of her as an artist and grotesquely

considered her more ‘has been’ than the legend she would arguably remain until

the very last act of her professional life. By 1952, Crawford was already well

into the ‘warrior princess’ phase of

her movie career; her once glycerin facial features acquiring a rather

square-jawed harshness; perhaps hastened by her bouts of alcoholism.

Personally, I

think Crawford and Palance are well-suited to each other in Sudden Fear; neither particularly

desirable physical specimens; Crawford, once the epitome of all ‘shop girls makes good’, now, undeniably

past her peak, and Palance possessing some of the most deceptively weird and

audacious angularity of any man ever to appear on the screen; their combined

ugliness transmitted equally by and through their respective character’s

actions (reactions) to one another - even more enterprising and vindictive in

the picture’s third act; a harrowing game of cat and mouse with a killer

(literally and figuratively) trek through the back alleys of Frisco under the

cover of night, ending in a tragic case of mistaken identity, murder and death –

how very Shakespearean indeed! We really

need to give Joan Crawford top marks; a star to the bitter end, unrelenting in

her pursuit of perfection. Even in the campiest or flimsiest of screen vehicles

(most coming near the end of her career) she could exude a sort of careworn

regality; the aged glamour queen gone hopeless to seed, yet utterly refusing to

accept the inevitable passage of time. Crawford’s pluck and guts could likely

respect the megalomania of a Lester Blaine, possibly because Crawford equally possessed

this unflattering characteristic; an affliction later to be abused and with even

more incendiary contempt, to be remade as the butt of a truly bad joke – and horrendous

‘tell all’ bio written by her vindictive adopted daughter.

We ought not

qualify nor quantify the content of Joan Crawford’s character by the notions

conceived about her in Mommie Dearest;

nor entirely discount the intent of the woman who clawed her way through the

ranks of a star system that, at least in the infancy of her career, frequently

conspired against her until only the public’s adulation cobbled together with a

studio’s greed to exploit their ‘new find’ led to the re-conceptualizing of her

image, starting with a name change. In Myra Hudson, Joan Crawford has found a

kindred spirit; a woman stricken by genius and in desperate need of proving

something to the world. Unlike Crawford, who began life impoverished and so hungry

for success, Myra Hudson is an accomplished lady of leisure. Time and

circumstances have favored Myra with privilege and money. Yet, Myra and Joan

are otherwise first cousins in their resolve to disentangle themselves from the

incidents of their upbringing. In Crawford’s case, this proved all to the good

as time passed and for a very long time thereafter. Alas, her alter ego is in for a rude

awakening.

Crawford had

devoured author, Edna Sherry’s Sudden

Fear with relish; a book in whose heroine she felt an immediate connection

and, as a freelance artist, ambitiously pursued as the project to re-re-launch

her waffling career. It should be pointed out some of Crawford’s most ambitious

projects were still ahead of her in 1952; although arguably neither she nor

Jack Warner could conceive of as much then. Much to Crawford’s initial dismay,

Sherry’s novel had already been optioned by indie producer, Joseph Kaufman.

Nevertheless, Crawford made her ambitions for the part known to Kaufman who

could neither afford her going salary nor expect she would play the part for

anything less. Crawford surprised Kaufman by agreeing to forego her take for

40% of the profits instead; Kaufman’s acceptance of these terms netting his

star a cool million after Sudden Fear

became an unqualified sleeper hit. Crawford would further her own stake in this

production by essentially becoming its de facto associate producer; demanding

and getting screenwriters, Lenore J. Coffee and Robert Smith, also director,

David Miller to partake of the exercise. Crawford’s star pull in getting

exactly what and who she wanted out of Sudden

Fear cannot be overlooked or dismissed. Certain, in agreeing to direct the

picture, Miller was to initially put his foot down on the matter of ‘creative

control’, bluntly telling Crawford that once his name was signed on the dotted

line he reserved the right to tell her “to

go fuck herself” should Crawford – ever the perfectionist – rear an ugly

head in an attempt to usurp his authority. Amused by Miller’s cheek, Crawford willingly

agreed to his terms, acquiring an immediate respect for both the man and his

work ethic thereafter.

Sudden Fear opens with New York tryouts for Myra Hudson’s new

play – aptly titled, Halfway to Heaven.

Her fastidious attention, only to actor, Lester Blaine’s outward appearance has

sincerely overlooked the fact he possesses other rewarding characteristics

ideally suited for the part of the ‘great lover’. Nevertheless, Myra has the

play’s director, Bill fire Lester. Lester’s confronting of Myra about the

physical shortcomings of Casanova is an early high point in Jack Palance’s

performance in Sudden Fear; soon to

be amplified by another unanticipated sequence of events. Despite Myra’s

shortsightedness, her latest Broadway offering is the toast of the theater

season. Months effectively pass in just a few carefully orchestrated and

extremely brief scenes; Myra, bidding her secretary and producer farewell to

return to the West Coast, even as Halfway

to Heaven continues to sell out to record audiences. Inadvertently, Myra comes in contact with

Lester Blaine again. By now, both have softened in their opinion of the other.

She invites him to her private train compartment and the two resolve to share

all their meals together in the dining car. Lester’s intimate reflections of an

imperfect past endear him to Myra. By the time the train has reached San

Francisco, Myra is hopelessly in love, confiding in her attorney, Steve Kearney

(Bruce Bennett) her intentions to marry this man she once described as lacking

the necessary ‘oomph’ to convince any woman he could melt her heart like

butter.

Lester is

penniless and frankly just the sort of fellow to set off a few red flags with

Steve until he discloses to Steve a need to find suitable work for himself;

refusing to become an appendage in Myra’s well-heeled lifestyle, leeching off

her millions. Steve is completely taken in by Lester and so is Myra, who

continues to consider herself the luckiest woman in the world for having found

the right man to satisfy all her needs. Alas, a chance meeting with a woman

from Lester’s past, Irene Neves (Gloria Grahame) is about to wither to chalk these

blossoming hearts and flowers. Lester is briefly repulsed by his first reunion

with Irene; a poison in his blood he quickly realizes he would rather be sick

in heart with than contented without and living with Myra. Part of Sudden Fear’s success relies on the

fact we are never entirely certain whether Lester has deliberately planned all

of this from the getgo. Sherry’s novel was rather clear cut about Lester’s

duplicity; once spurned by Myra and deprived of his chance to become a big star

in her play, now hellbent on marrying, then murdering her to gain access to her

wealth so he and Irene can run away together. Too bad Myra has decided to give

away all of her familial wealth to charity, living off the stipends and

residuals from her plays. There are remnants of this betrayal lingering in

Lester and Irene’s initially caustic exchanges of dialogue out of Myra’s

earshot, though not beyond being recorded by her automated Dictaphone in her

private study; Irene suggesting to Lester she has returned into his life after

having read of his society marriage in the papers, hoping to blackmail him as

the kept woman on the side. Herein, Gloria Grahame exhibits the early hallmarks

of Debby Marsh, the gun moll she would play in The Big Heat one year later, with tinges of Laurel Grey, the

sad-eyed/street savvy/love-naïve gal she had already given over to opposite Humphrey

Bogart in In A Lonely Place (1950).

Irene and

Lester’s clandestine rendezvous go unnoticed by Myra. Nevertheless, Irene makes

Lester quite jealous by simultaneously pursuing a relationship with Steve’s son,

Junior (Mike Connors); a budding attorney at law who is oblivious to the fact

he is being used, merely for the luxuries his moneys can provide. Myra does not

suspect the man in her life of infidelity and is shocked to the brink of

becoming physically ill after discovering the hidden recording of Lester and

Irene plotting her swift demise. But fear turns to calculated revenge.

Accidentally smashing the record, thus destroying evidence to support any claim

she could make against Lester’s complicity in her death, Myra concocts a series

of insidious and vindictive passive/aggressive confrontations, gradually

causing Lester to suspect she knows much more than she is letting on. Even so,

he is unable to bring Myra to a confession and thus, the game of cat and mouse

evolves with Myra faking a tumble down the steep staircase of their home on the

eve she was supposed to attend the opera with Lester and a small contingent of

their friends, including Irene. Myra also thwarts a plan she initially approved

of, having Lester drive out to the country house where they spent their

honeymoon, presumably to make ready for a weeklong retreat, but actually, just

another of Myra’s ploys to get Lester away for the afternoon while she steals

his key to Irene’s apartment and has a copy made for herself.

Myra’s revenge

scenario kicks into high gear after she breaks into Irene’s apartment to search

for tangible clues. After she skulks off in the dead of night with Lester’s stolen

pistol, intent perhaps either on murdering Irene and blaming the homicide on

Lester, or waiting for the two lovers to reunite so she can kill them both in

the throws of passion, Myra instead suffers a crisis of conscience upon

catching a glimpse of herself in the mirror. Preparing to leave Irene’s

apartment, she is instead forced to hide in the closet after Lester arrives

unexpectedly and lets himself in to wait for Irene. In one of Sudden Fear’s best recalled scenes of

screen suspense, Lester plays with a wind-up toy, placing it on the floor and

casually observing as it steadily approaches the closet, unaware Myra is hiding

just beyond and utterly terrified she will be discovered by him. Instead, an interrupted

telephone call diverts Lester’s attention. Discovering his own gun on the floor

nearby, Lester assumes Irene is already dead from a self-inflicted gunshot. He

reacts in panic, frantically searching the apartment, leaving the room for only

a split second and returning to find the closet door wide open and, the front door

to the apartment unlocked. Putting two and two together, Lester realizes Myra knows

about his affair. He rushes out of the apartment and catches a fleeting glimpse

of Myra fleeing on foot. Lester races after Myra in his car, intending to run

her down in the streets. She repeatedly eludes him by ducking into the back

alleys and scurrying down dark byways that prevent his pursuit except on foot.

Lester is unaware of the fact Myra and Irene, newly returned home from a date

with the younger Kearney, is similarly attired in a fur and head scarf, making

her appear as Myra from a distance as she hurries up the steep incline back to

her apartment. Determined to put an end to his wife once and for all, Lester drives

his car up onto the curb and sidewalk, striking and killing Irene and himself

in the process. Having witnessed this harrowing case of mistaken identity from

a safe distance, Myra marches off toward the horizon where the dawn has begun

to crest; a queer look of absolute vindication about her face. Her ordeal is at

an end.

For all its

suspense, Sudden Fear is a rather

feckless, if occasionally diverting, and – in spots – marginally entertaining

post-MGM/Warner Bros. high point in Crawford’s career. Indeed, the picture was

so successful at the box office it led to several Academy Award nominations and

a re-invigoration of Crawford’s career prospects, this time over at Columbia

Pictures. Unfortunately, the plot is conventional to a fault and greatly

altered from Sherry’s novel – a genuine and enduring page-turner. I mean, a

rich woman marrying a man who intends her harm…this is a Dateline episode at best. As such, we really owe Crawford props for

managing to pull off much of Sudden Fear’s

sincerely flawed and marginally contrived caper/foiled murder scenarios. The

picture’s plotting is uneven at best; its first act given over to exactly the

sort of homogenized Crawford melodrama that had become something of a clichéd

standard by 1952 after achieving the height of its popularity in the infinitely

more appealing, and sadly still absent from Blu-ray mystery/thriller, The Damned Don’t Cry (1950), made and

released two years earlier. Sudden Fear

has the look of a Crawford movie made at Warner Bros. but not its’ ‘ripped from the headlines’ immediacy to

make the action stick. Sudden Fear

was independently made by Joseph Kaufman and distributed via RKO Pictures who

otherwise had absolutely no involvement in its production. At 110 minutes, Sudden Fear seems overly long in its first act and just a tad too

brief in its dénouement to be entirely effective.

Director David

Miller uses the San Franciscan locations to optimal effect, particularly during

the penultimate chase between Myra and Lester – arguably the second greatest

scene in the movie, narrowly trumped by the aforementioned ‘closet’ sequence where Myra sweats

bullets as Irene’s wind-up toy steadily approaches her secret hiding place with

Lester obtusely unaware she is observing his every move. If only the rest of Sudden Fear had lived up to these two

pivotal sequences in screen tension it might have been a considerably more exhilarating

thriller. Sudden Fear also lacks

badly needed humor; a commodity all too familiar in a Hitchcock thriller to

counterbalance the tautness and break up, though never diffuse, the mounting elements

of terror. And then there is la Crawford’s performance to reconsider; superb

for the most part, but prone to at least two moments of overwrought play

acting, threatening to devolve into pure camp. The first instance is Crawford’s

reaction as Myra to hearing for the first time the recording of Lester and Irene

plotting to do away with her. Crawford’s expressive eyes dart wildly, her

pacing about the office, arms raised with fists clenched and pressed against

her cheeks, is about as laughable as scenes depicting the ‘terrorized female’

can get. But it is Crawford’s reaction to Myra holding Lester’s revolver in

Irene’s apartment that wins the gold star for ridiculousness: her character

discovering just how close she has come to committing murder, rather idiotically

overplayed; Crawford turning from her own reflection in Irene’s mirror to the

gun in her hand, back and forth, with mounting dread, panic, disgust, and the

wicked realization that, under the right circumstances, she and Lester are very

much kindred in their passion to do one another great harm.

Jack Palance

is far more believable in the early scenes where he ruthlessly and rather

sinisterly plots against Myra with Irene. Part of Palance’s success is directly

correlated to his aforementioned spooky physical features. He just looks the

part of the villain so completely that to see him unravel into a scared little

boy at the end, eratic in his pursuit of Myra both on foot and by car, when a

cruel plotter like Lester Blaine ought to have caught up to Myra at least a

half dozen times and taken her to task and an early grave, deprives us of the

rather insidious competency Lester otherwise possesses. The rest of the cast are

wasted in Sudden Fear. Even Gloria

Grahame lacks the potency earlier exhibited in In A Lonely Place; Irene, very much the conniving bitch, but given

all too few scenes to truly mark her as an enterprising third wheel in this

equation. Exactly how much of Grahame’s lack of participation herein was

dictated by Crawford’s need to be ‘the star’ of the piece at all times is open

for discussion. Certainly, Crawford could afford to be magnanimous and yet,

frequently exercised a streak of jealousy to keep her female costars off the

screen and minimize her competition. Grahame, who could run the gamut from

playing disarming dim bulbs like Ado Annie in Oklahoma! (1955) to clear-eyed street-savvy tricks like circus

performer, Angel in The Greatest Show on

Earth (1952) is regrettably wasted in this walk-on cameo; Irene never presented

as anything more involved than the sly gal on the side. Bruce Bennett, who costarred

to better effect with Crawford in Mildred

Pierce (1945) is put out to pasture here; a thankless part in service to

the diva. In the final analysis, Sudden

Fear is Crawford’s picture through and through, and, she chews up its

scenery at a considerable expense to her costars.

Chewed up is a

good way to describe Cohen Media’s Blu-ray release. Reportedly mastered from a

brand new 2K transfer, I can only speculate the original elements were in very

bad shape indeed. For starters, the B&W image looks to have been sourced

from less than perfect second or third generation elements; contrast severely

boosted in spots, enough to wash out all fine detail and bleach any tonality in

flesh to a ‘Casper the friendly ghost’

white. Close-ups fare the best. Occasionally, the image even snaps together

with some very complimentary detail in hair, skin and fabric. But the overall

quality – or lack thereof - just seems ever so slightly out of focus and/or

soft; film grain, much clumpier than anticipated. Again, 2K remastering is

capable a far better than this so the source is likely to blame and not the

mastering effort per say. Age-related artifacts have been tempered rather than

eradicated. On the whole, the image is too severely contrasted to be enjoyed.

Day scenes in particular are much too bright. Whites sporadically bloom but

never toggle down to anything less than a distracting glare. The 2.0 DTS mono

audio is strident in spots, illustrating hiss in quiescent scenes that more

efficient mastering could have greatly modulated and/or cut out almost

entirely. Unusual for Cohen, we get virtually no extras on this disc, save a

fairly comprehensive audio commentary by TCM Essentials historian, Jeremy

Arnold. Actually, Arnold’s verbal notes on the background and making of this

movie are the best thing about this disc. Personally, I would have settled for

a better mastering effort. Regrets.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

3.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

3

EXTRAS

1

Comments