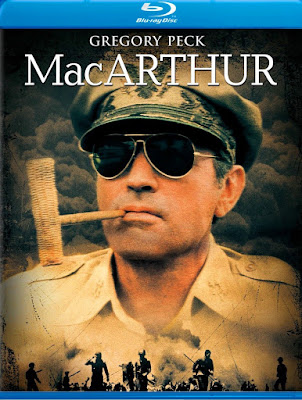

MacARTHUR: Blu-ray (Universal 1977) Universal Home Video

The real Gen.

Douglas MacArthur once astutely pointed out “old

soldiers never die…they just fade away”; regrettably, as is the case for

director, Joseph Sargent’s MacArthur

(1977); an oft affecting, but only partial biography of this legendary, and some

would still argue as ‘infamous’ historical figure. Embodying the role is

Gregory Peck; Hollywood’s man of integrity, cast in a part he neither sought

nor desired, and, at the outset, actually somewhat detested, along with just

about every other aspect of the production. “I

admit that I was not terribly happy with the script they gave me,” Peck

later recounted, “…or with the production

(confined) mostly on the back lot of Universal. I thought they shortchanged the

production.” Miraculously, Mario Tosi’s diffused low-key cinematography,

married with master SFX artist, Albert Whitlock’s superb matte paintings, and,

some reasonably culled together WWII stock footage, manages to mask Universal’s

paltry $9 million budgetary restriction. MacArthur

is a picture that deserves more notoriety, not the least for Greg’s

im(peck)able performance as the caustic, clear-eyed and forthright military man

of vision; his long-reaching plans for peace during the Korean conflict cut

short by Washington’s entrenched bureaucracy. The point in Hal Barwood and Matthew

Robbins’ screenplay is politics does not respect men of action, neither their

divining and unfiltered heroism; viewing MacArthur’s own precepts of ‘honor,

duty and country’ as subservient to their congressional willpower and

self-professed authority. Hardly shot on a shoestring, though decidedly lacking

the production values one might anticipate, MacArthur made money for the studio in 1977. Yet today, it somehow

lacks the staying power of Franklin J. Schaffner’s 1970 masterpiece, Patton; the movie that effectively

kick-started a renewable trend for military bio/pics.

As a military

strategist, the real Douglas MacArthur’s intuition was both potent and uncanny.

Like Gen. George S. Patton, MacArthur seemed to instinctively recognize where

the enemy’s pressure points and weaknesses lay and knew best how to distress them

to bring about a swift resolve in his favor. Frequently, he went over the heads of his

superiors, including President Harry S. Truman; using his mass appeal and

popularity at home to back his efforts. And like Patton, MacArthur suffered

from ego, stitching together his legacy as he willfully spent the blood, sweat

and tears of many a young private, sergeant and otherwise engaged military

personnel serving under his command, never to find their way back home to that

thought-numbing ticker-tape parade that greeted MacArthur upon his return to

the United States. There are those who consider Douglas MacArthur a legend in

his own time…and others to whom his very name is an anathema to peace.

MacArthur always said “no one values

peace more than the soldier…for only he truly knows the horrors of war up

close.” And yet, MacArthur repeatedly found ways to pursue his combat

strategies, despite often being asked to reconsider his taciturn approach until

cooler heads and the art of diplomacy could have their crack in invested

interests.

Gregory Peck’s

take on MacArthur is oddly unbalanced; first, by the Barwood/Robbins’

screenplay that zeroes in on platitudes and speeches in lieu of and genuine

exchanges in dialogue. MacArthur is

brimming with superlative wit, wisdom and pontifications about the futility of

war. These excerpts are, in fact, expertly handled by Peck, who occasionally

veers into the lyrical strain of a hellfire Sunday sermonizing backwoods

preacher. During these orations one could almost imagine his Douglas MacArthur

feasting on bullets for breakfast; the sound of roaring canon fire split

between his ears and spitting strychnine from his corncob pipe with marksman

like precision to poison and cripple his enemies. If only MacArthur were not an

intellectual military strategist. The second hindrance to the production is regrettably

Peck’s stodgy stoicism; seemingly determined to pay homage to a monument, but

queerly mislaying the man of flesh and blood lurking underneath that entire newsreel-gleaned

public persona the real MacArthur worked so diligently to craft, maintain and

shamelessly promote.

MacArthur begins at the twilight’s last gleaming of the great

man’s legacy; addressing the impressionable West Point cadets during their

commencement exercises. We catch glimpses of a sad, faraway look in Mac’s eyes.

Indeed, he has been to hell and back, as we quickly regress to 1942, the height

of the conflict. MacArthur is embroiled in a miscalculation of American might

in the Philippines on the eve it is about to be overrun by Japanese forces.

Douglas is not about to give in and beseeches President Roosevelt (Dan

O’Herlihy) for the necessary reinforcements and supplies, earlier promised the

Filipino and American forces to see through the battle of Bataan near

Corregidor Island. Alas, the U.S. stronghold is all but lost. Simultaneously in

Washington, General George Marshall (Ward Costello) and Admiral Ernest J. King (Russell

D. Johnson) deliver this grim news to Roosevelt. The President’s hands are tied; too heavily

invested in the fight in Europe to spare either supplies or troops to relieve

MacArthur. Concluding that the imminent

capture of MacArthur would wound America’s reputation and morale in the war effort,

Roosevelt orders his ‘four star’ general to take a commission in Australia – also,

in danger of invasion by the Japanese. Begrudgingly,

MacArthur departs the Philippines, along with his wife (Marj Dusay) and young

son (Shane Sinutko); leaving Gen. Wainwright (Sandy Kenyon) and a devoted

Filipino fighter, Castro (Jesse Dizon) to face the cruelty and capture on their

own; vowing “I shall return” and

damned determined to do so, despite Roosevelt’s orders.

MacArthur’s PT

boat is in constant danger as it sails for Australia under the cover of night, encountering

floating mines. Miraculously, no Japanese destroyers prevent its safe passage.

But in Melbourne MacArthur learns the bitter truth: there never was a plan to

supply him with badly needed relief for the Philippine invasion. Recognizing he

has likely left some of his best men to die in the jungle, MacArthur grits his

teeth, girds his loins, and addresses the thronging masses in Melbourne. Plotting

almost immediately to fortify Australia’s flank by invading the Philippines once

more, MacArthur is told Corregidor and Bataan have fallen, leaving 70,000 to

imprisonment, starvation and torture. Refusing to believe all is lost,

MacArthur launches into a daring campaign across the jungles of New Guinea. His

gains are hard won under the most hellish conditions. To minimize casualties, he evolves an ‘island

hopping’ strategy, circumventing the Japanese strongholds and cutting off their

supply lines. Two years of tremendous bloodshed in the Southwest Pacific culminates

in MacArthur’s ‘invitation’ to meet with Roosevelt and Admirals Leahy (John

McKee) and Nimitz (Addison Powell) aboard a U.S. destroyer; a PR junket

MacArthur utterly abhors, illustrating his displeasure by arriving late to the

gathering.

The

relationship between Roosevelt and MacArthur is strained. However, Roosevelt

can certainly recognize MacArthur’s passion, as well as his strengths, even as

Mac’ calls out the President to remember promises made to these loyal Filipinos

who have invested everything to side with America in the face of their own

annihilation. In the end, and despite Roosevelt almost having made up his mind

to follow a course to invade Taiwan first, the President instead makes the

executive decision to listen to MacArthur and prepare for the liberation of the

Philippines. US forces stage a daring assault in the Leyte Gulf in October,

1944. In spite of their tenuous toehold on the coastline, MacArthur insists on

going ashore with his men, wading knee-deep in water to address the Filipinos

by radio, exhorting them to drive out their Japanese oppressors. Accompanied by

Filipino President Sergio Osmena, who awkwardly informs MacArthur he cannot

swim, MacArthur’s gentle and self-deprecating reply, “That's not so bad, Mr. President. Everyone's about to see that I can't

walk on water” gives Osmena, as well as the troops, hope to advance onto

victory. As the tide begins to shift in MacArthur’s favor he is awarded his

fifth star; taken to a nearby liberated POW camp where emaciated Americans and

local freedom fighters, captured by the Japanese, have been tortured and

brutalized. There, MacArthur is reunited with a tearful Castro; half-stripped

and on crutches, apologizing he is not fit to receive the general. In reply,

MacArthur embraces his old friend, suggesting he could have anticipated no

finer a reunion. Aboard his ship, MacArthur receives another unlikely friend;

Wainwright, fragile and driven to the brink of a nervous breakdown. The men

acquit themselves of a tearful reunion. But soon thereafter news reaches

MacArthur that Roosevelt has died.

His successor,

Harry S. Truman (Ed Flanders) is a reluctant Commander in Chief, authorizing

the use of two atomic bombs to bring Emperor Hirohito (John Fujioka) to his knees.

MacArthur is opposed to this ‘impersonal’ warfare. Indeed, the bombs dropped on

Hiroshima and Nagasaki usher a new age in which enterprising war strategists

like MacArthur will increasingly discover themselves to be obsolete. MacArthur

presides over the articles of surrender aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Now

appointed as an Allied military governor in Japan, MacArthur institutes

sweeping social reforms and oversees the reconstruction of a modernized nation.

Hence, when Russia’s military diplomatist , General Derevyanko (Alex Rodine)

coolly threatens to use his forces to occupy Hokkaido Island, MacArthur coyly

promises, should any such action even be uttered in hushed debate, the entire

Soviet delegation responsible for its consideration will be emphatically thrown

into prison. As all know Mac’ as a man of his word, he is taken quite seriously

and the occupation of Hokkaido never occurs. While his time spent rebuilding

and reshaping the social mores and political machinery of this new Japan prove

mostly gratifying, MacArthur grows increasingly restless. Thus, in June 1950,

he is given an opportunity by Truman to return to form – and uniform – after

Communist North Korea invades South Korea. Appointed Supreme Commander of the

UN forces, MacArthur bides his time, plotting a risk-laden amphibious landing

at Inchon. For the first time, Mac’ is uneasy about his decision. Nevertheless,

it proves sound. North Korean forces are cut off from their supplies and

reinforcements; forced to retreat northward in utter chaos.

Despite

Truman’s reticence to take the fight to the other side, MacArthur now charges

into North Korea causing Communist China to re-enter the fray as North Korea’s

ally. UN forces incur heavy casualties and Truman, always exacerbated by his

own ineffectualness to ‘manage’ MacArthur from afar decides to lower the boom,

recalling Mac home on grounds of insubordination. And just like that, Douglas

MacArthur is promptly relieved of his command. Perhaps Truman always feared

MacArthur’s popularity. Alas, MacArthur’s bid for the Presidency never quite

came off; MacArthur, nevertheless forewarning Truman’s real threat is Eisenhower;

the candidate Truman least suspects and fluffs off. MacArthur arrives in New

York in 1951, given a hero’s welcome while Truman’s popularity nosedives in the

polls. At last given the opportunity to speak his mind, Mac delivers a gripping

farewell to the joint session of Congress. He is given a standing ovation by

his well-wishers and pundits alike. In the movie’s final moments we return to

West Point and Mac’s address to the graduating class of 62’, stressing that a

life devoted in military service must stress the principles of ‘duty’, ‘honor’

and ‘country’.

MacArthur ought to have been a more moving tribute to the man of

the hour. The picture needed the almost ‘respite-like’ moments of introspection

afforded actor, George C. Scott in Patton,

where Scott brilliantly allows his audience to see ‘behind the veil’, the

flashes and the foibles of a genius in his element and at play. Arguably, true

military men have no private soft side. But Scott’s Patton is a renegade with

an Achilles’ heel. Peck’s MacArthur is merely an orator who faithfully believes

in his own verbiage, come what may. MacArthur

might have greatly benefited from the sort of antagonistic buddy/buddy

byplay afforded Scott and co-star, Karl Malden as Gen. Omar Bradley.

Comparisons between Patton and MacArthur – the movies – are

inevitable; each serving as a bookend to the 70’s verve for re-imagining heroism,

occasionally with a war-mongering slant. The battle over how ‘free’ freedom is,

rages on to this day; conscientious objectors still launching into their

protest marches with mis-perceptions about a soldier’s valor. If we are to

consider MacArthur – the movie and

the man – with a benediction of any sort we must first come to an acceptance of

war as that ‘necessary evil’ brought by men from differing socio-political views;

a point of embarkation where the only proportionate response is retaliation from the opposing side.

Wars are rarely fought for the most altruistic purposes. And history – nee ‘fact’

is always writ from the perspective of the victors. Is this just or even

accurate? While some will undoubtedly continue to debate – even lament – this

as much as the freedoms we have enjoyed, afforded us by those taken up the

cause at the point of a gun, there is little to deny a soldier his/her honor

system of checks and balances, beliefs and bravery. We sleep more soundly

because others like a Douglas MacArthur accept responsibility for our welfare. Without

ever having served, and personal opinion of course, I firmly believe in the

military and its might to stand against those who would seek to dismantle our

way of life. MacArthur – the movie –

offers glimpses into that investment of energies and time afforded one man; a portrait

regrettably, without any soft-centered deconstruction of his motivations. It’s

not a terrible tribute. However, it remains a very incomplete one at best.

I have sincerely

given up on Universal Home Video to do right by their catalog on ANY video

format. For one reason or another, the studio’s track record has been among the

worst of any major studio pumping out older movies to any disc format. Does

anyone at the studio know anything about quality control? Is remastering a word

on their radar? Is there no respect for history…movie history, that is? But I

digress. MacArthur's 1080p Blu-ray

is barely adequate. For starters, the main title opticals are severely faded

and suffering from a bizarre color implosion; West Point cadet’s grey uniforms

appearing muddy powder puff blue, the sky looking greyish purple and flesh tones

veering from piggy pink to ruddy orange. It’s a garish start to an otherwise un-extraordinary

presentation. Okay, Uni – let’s get off the pot about advertising ‘perfect HD picture and sound’ on the

back jackets of your discs when virtually nothing apart from packaging appears

to suggest otherwise! You are dangerously close to ‘false advertising’!

Colors crisp

up – marginally – after the main titles. Flesh tonality evens out to a dull,

pasty orange. The entire spectrum settles into mid-grade plunk – listless and

ugly. Everything from the supposedly lush green tropical vegetation to military

khakis appears in an almost monochromatic register. Interiors look even worse.

Detail is wan at best, except during close-ups. There is also some very minor,

intermittent gate weave. I am equally

amazed Uni has spent the extra coin to offer a DTS 5.1 audio of a movie originally

released in 2.0 mono. It’s rechanneled ‘stereo’ of course, exposing the

shortcomings in overlapping dubs and only occasionally offering some exotic

spread across all five channels – mostly, during the action sequences. Dialogue

is very frontal sounding and tinny. My last bit of displeasure: Universal goes

the quick n’ dirty route: NO chapter stops, except by advancing at 10 minute

intervals. No main menu screen either. Remember when Blu-ray was supposed to

offer all the bells and whistles no other home video format could? At the risk

of ruffling more than a few feathers – MacArthur

on Blu-ray is about as passionless an example of what hi-def is capable of,

even at a glance. Abysmal releases such as this are the norm for Universal.

There is no good reason to believe their outlook for future deep catalog

releases will be any better. Ugh! Frustrating! Regrets!

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

3

VIDEO/AUDIO

1.5

EXTRAS

0

Comments