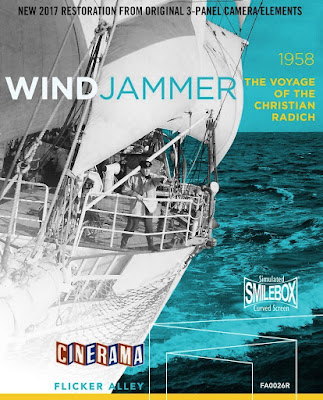

WINDJAMMER: The Voyage of the Christian Radich (National Theatres, 1958) Flicker Alley

I do not recall

ever beginning a movie review with a plaudit paid to an effort made some 60

years after the initial theatrical release; but the Herculean resurrection

achieved by film restorationist, David Strohmaier and his team of creative

geniuses on director, Louis de Rochemont’s Windjammer:

The Voyage of the Christian Radich (1958), co-directed by the producer’s

son, Louis III and Bill Colleran (husband of Lee Remick), ought to be held in

the highest regard as an exemplar of what real/reel film restoration/preservation

work in this digital age is all about. Strohmaier and his cohorts were, of

course, responsible for the 2008 Blu-ray release of Windjammer; Strohmaier’s passion for all things Cinerama, then superseding

the technology and funds necessary to make his first outing on this deep

catalog release a total success. Cribbing from a re-composited Cinemascope image

then, the results in 2008 could only be judged as adequate. Even then, I could

not have thanked Strohmaier enough for his splendid interest in reintroducing

newer audiences to this vintage piece of American cinema history – for much too

long, forgotten and withheld from public view.

But now, with

2018’s Blu-ray re-release through third party distributor, Flicker Alley,

audiences will at long last get to see Windjammer

in as close approximation to its former glory theater attendees were privy to

back in 1958. Culling elements from around the world, including original camera

negatives and IP’s, Windjammer’s

3-panels have been scanned at 4K and color graded to reveal the extraordinary

camera work of Joseph C. Brun and Gayne Rescher. Is it a perfect rendering? Alas,

no. Time has not been on Windjammer’s

side, and, on occasion, the results of decades-long neglect remain too great,

even for Strohmaier’s ardent tenacity to overcome. What is here, however, is superb beyond virtually any and all

expectations. Windjammer is a

visceral, sumptuous and rousing experience: even for Cinerama - a true rarity

in a class apart; the only movie to be photographed in ‘Cinemiracle’ – a then

newly patented and slightly tweaked version of Cinerama – its left and right

cameras, shooting into mirrored reflections that, once reversed and recombined

in the editing process, recreated the total scope of human peripheral vision.

Windjammer is such a remarkably exquisite movie-going experience

that its technical aspects - a logistical nightmare by any stretch of the

imagination – have been completely obscured. As example: how does one hoist a

500 lbs. Cinerama camera some 180-feet between dense rigging and sails to

achieve all those miraculous overhead shots, looking down onto the decks of the

square rigger, Christian Radich, at times, violently bobbing about like a cork

caught in a gale? Indeed, on this particular Cinerama adventure, the Radich and

its crew were to encounter one of the worst storms at sea ever documented on

film, race within mere fathoms of a U.S. naval destroyer (with the very real

threat of suffering a collision), and, unbeknownst to anyone at that time,

chronicle the last visual record of Germany’s equally as famous four-masted

barque Flying P-Liner, the Pamir – lost

in a hurricane off the Azores only a few days later, with only six of her 80+

crew surviving the ordeal. After the Pamir’s disaster, it was also decided by

De Rochemont that a few connective scenes should be photographed in

post-production to pay homage to her ship and crew. Thus, Sven Libaek and his

cohorts, Lasse Kolstad, Kaare Terland, Alf Bjerke and Kjell Grette Christensen

(who had formed a quartet aboard the ship, later to record an album for

RCA/Victor, grouped as ‘The Windjammers’)

were all flown to New York to shoot scenes on a studio-bound recreation of the

Windjammer’s club room.

Setting aside the

Christian Radich’s six-month, 17,500-nautical-mile globe-trotting voyage from

Oslo, across the Caribbean to New York and then back again, De Rochemont and

his real-life staff of novice sailors (some as young as fourteen) are to be

commended for their blind vision and technological proficiency along the way.

Rumored to be displeased with Colleran’s objectives shortly after embarking

upon the project, producer, De Rochemont installed his son, Louis III as the de

facto director midway through the shoot; a decision that did not immediately

ingratiate the 28-yr. old to the rest of the troops. However, almost as quickly

they realized Louis not only possessed a keen eye for visual storytelling but

also the aptitude to helm such a titanic and all-encompassing journey

documented on film. In a fascinating postscript, young Louis’ eye caught the eye

of a lass from Oslo who would appear on camera in the movie briefly. Although

smitten, when production of Windjammer

wrapped, Louis and the girl went their separate ways. Fate, however, had other

ideas, and, in 1977, the couple were reunited during Louis’ return to Norway.

They married; Turi De Rochemont remaining at her husband’s side until his death

in 2001.

The Christian

Radich was then, a training ship for Norway’s merchant marine – a proving

ground held in considerably high esteem, where boys were sent to become men;

many making a life for themselves as sailors thereafter. For Windjammer,

producer, De Rochemont charted a 9-month excursion through the English Channel

to the isle of Madeira, crossing the Atlantic with pit stops along several Caribbean

outposts and finishing up in Key West, Florida; then, running up the coast to

New York City, Portsmouth and New Hampshire, before making a round trip return

to Norway across the top of Scotland; an ambitious slate indeed, given the

added expense and burden of importing a sizable film crew and the monstrous

Cinemiracle camera along for the journey. In addition to the Christian Radich’s

usual training cadets and officers, De Rochemont so ordered a few fresh faces

brought aboard, Norwegian actors whom the audience could relate to and around

whom the central narrative would be woven.

One of these hallowed chosen was Sven Libaek, a 17-yr. old aspiring

pianist who would secure a plum spot performing the solo in Edvard Hagerup

Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A minor

opposite renown conductor, Arthur Fielder and the Boston Pops; a performance

interspersed with some gorgeous pastoral cutaways of the Norwegian countryside.

Indeed, permission for Libaek to sail on the Christian Radich was granted by his

mother, only after she insisted a piano be brought aboard so the young man

could continue his practice while away from home; the upright lashed to a

bulkhead to prevent it from careening back and forth during inclement weather.

The making of

the Windjammer is worthy of a novel

in and of itself. Its 17 officers and 85 young men were exposed to some of the

most exhilarating, but also most harrowing conditions on their epic 200+ day voyage;

not the least, dangling from the ship’s yardarm and rigging 180 ft. above sea

level with the motto, ‘one hand for the

ship, the other for yourself.’ Barreling past the English Channel at 18

knots, the Christian Radich encountered its first major obstacle; a perilous

winter storm with mountainous waves in the Bay of Biscay, causing most of her

novice crew to become violently seasick. Under such hellish conditions the

excitement of being in a Hollywood-produced documentary easily evaporated, everyone

suddenly invested in the survival of the ship. Passing through the gale without

incident, what followed was a spring-like sojourn to the isle of Madeira, first

discovered by Portuguese explorer, Zarco in 1419 – their arrival in Funchal

captured by the weighty Cinemiracle cameras.

Here, the camera would also document, among many pleasures, the famous

downhill slalom of the basket sleds before embarking, under favorable Trade

Winds, onto their next port of call – San Juan, Puerto Rico, following the same

route Columbus took in 1492. It was

during this league in the expedition the Christian Radich fatefully encountered

the four-mast German barque - Pamir, herself en route to Montevideo, Uruguay;

both crews, in high spirits, shouting salutations to one another as they passed

– literally – like two ships in the night.

Puerto Rico’s

visitation was populated by invitations and parties, capped off by a lavish

reception at the Governor's Palace Fortaleza where cast and crew were treated

to a special performance by legendary cellist, Pablo Casals. For the next two

months, the Christian Radich made a pilgrimage of the Caribbean, incurring

production changes in St. Thomas, including Bill Colleran replaced as the

director – a decision never entirely disclosed by its producer. One incident

not captured by the Cinemiracle cameras occurred when Colleran’s wife, Lee

Remick elected to take a swim in the warm waters off the coast of Salt Island,

unaware of a nearby shark. Hurried into a small boat by some of the Christian

Radich’s crew, Remick would turn a ghostly shade of gray after witnessing ‘a

fin’ just several meters behind her. With renewed vigor, and Louis III now in

charge of completing the picture, production moved on to Trinidad and the

non-stop Calypso-ing at carnival in Port-of-Spain. Among the highlights for

cast and crew was a steel drum welcoming committee and the limbo dancers,

performing contortionist maneuvers to the rhythmic sway of kettle drums. From here, production proceeded to the Dutch

isle of Curacao. As the crew

disembarked, so too did the ship’s mascot, Stump take his own ‘unofficial’

liberty. As the dog was never recovered, De Rochemont found a suitable

look-alike to complete the footage. Departing for Key West, producer, Louis de

Rochemont made a fortuitous announcement, having arranged for Sven Libaek to

study with concert pianist, Bernardo Segal in New York, in order to perform

Grieg’s Piano Concerto with Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops in Portsmouth:

the musical highlight of the picture.

Meanwhile, the

Christian Radich pulled into New York harbor, by far the glossiest and most

impressionistic part of their journey captured on film; cinematographer, Arthur

'Weegee' Fellig, separating the 3-strip projection into a series of dizzying kaleidoscopic

imagery. From here, the Christian Radich engaged the U.S. navy in some

breathtaking maneuvers, involving sea planes, a submarine, several naval

destroyers and an aircraft carrier; the sequence, accompanied by composer

Morton Gould’s most bombastic orchestral arrangement. In Portsmouth, Libaek

displayed his musical prowess alongside the world-famous Boston Pops with

Arthur Fiedler conducting; his performance interrupted by a montage of

breathtaking snapshots of the Norwegian fjords. In the brief epilogue that

followed, news of the Pamir tragedy created a sobering postscript to

all the heady excitement gone before it; the pall, somewhat dissipated by the

Christian Radich’s safe arrival in Oslo, alongside the Danish ‘Denmark’ and Norwegian

‘Sørlandet’; her crew, greeted by cheering crowds and capped off by a

much-anticipated reunion with loved ones.

To say that the

filming of Windjammer was a

life-altering experience for many of its novice crew is an understatement.

Some, like Sven Libaek, would leave their native Norway for good to pursue

interests abroad. Indeed, even as principle photography wrapped, Louis de

Rochemont instructed five of the chosen young men and Lasse to report to a

studio in New York to shoot conjoining ‘inserts’ to evolve the storytelling,

coached in their English diction by Claudia Franck. Along with Libaek, former

shipmates Harald Guttersrud and Kaare Terland selected to remain in the United

States thereafter; Harald, to study drama at Yale, and Kaare, devoted to

business at Dartmouth, with Libaek eventually getting into Juilliard to

continue his music. This trio also became emissaries for the general release of

Windjammer, traveling on the

Superchief to open the picture in various cities – including Windjammer’s world-premiere at

Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood and its New York debut at the famed

Roxy; along the way, having tea with Rita Hayworth, and, also, forming a

singing trio that would regularly feature on popular radio and television

programs, eventually cutting an album for RCA/Victor and appear on stage at the

Grand Ole Opry.

With the passage

of time, Windjammer’s reputation as

a bona fide Cinerama adventure has only continued to grow, despite the more

recent loss of cast members, Jon Reistad, Lasse Kolstad and Alf R. Bjercke. Unlike many popular

entertainments of their time, left to molder with the past thereafter, as the

fickle public taste moves on toward the proverbial ‘the next best thing’, with

each passing year, Windjammer’s

legion of fans has continued to grow. Perhaps, by reputation alone, though

arguably because of its perennial promise of youth – as depicted by all those

bright-blue-eyed/blonde-haired Norwegian tough boys on the cusp of manhood – a

real ‘coming of age’ saga in its truest definition, Windjammer remains as celebrated today whenever it plays. And

thanks to the Herculean efforts of David Strohmaier and his restoration experts,

the resurrection of its glorious past has been brought back from the brink of

extinction for generations forever more to enjoy. Arguably, there is no

affecting way to see a picture like Windjammer

except in a real Cinerama venue; the vastness of its towering, louvered screen

suddenly breaking through the conventional proscenium of the 1.33:1 prologue to

reveal a spectacle unlike any other.

David Strohmaier’s

restoration is to be championed. Alas, it is not perfect. So, it behooves us to

point out the inherent flaws in this newly minted 1080p transfer, as

represented a second time around on Blu-ray. For starters, there is some

alarming edge enhancement during several of the sequences shot at night; Lasse

Kolstad’s serenade ‘Kari Waits For Me’

plagued by haloing and flicker in highlighted background detail of the ship’s

rigging. As this is the result of digital mastering, and not an inherent flaw

in the original camera negatives, it is, at least by my opinion, the biggest

disappointment. Is it a deal breaker? Certainly not, as there are only a few

intermittent instances where its presence becomes egregious and distracting. We

should also point out that despite a lot of dust-busting and digital clean-up

with some high-end tools provided by Boris FX, Flicker Free, FotoKem and Chance

Audio, the resultant image still reveals instances of color implosion and,

again intermittently, brownish seams between the center and two side panels of

the vast Cinemiracle frame. There are also one or two scenes shot under low

light conditions at magic hour that suffer greatly from color fading. Finally,

there is minor gate weave to consider; the left panel (more than the right)

prone to distracting wobble. Now, let us be clear here. Nothing short of a

multi-million-dollar restoration would correct these aforementioned sins,

inflicted upon Windjammer through

generational abject neglect.

And indeed, when

Strohmaier and his small army of passionate preservationists first encountered Windjammer’s original camera negative,

the likelihood anything could be done to restore and preserve it teetered

between downright sketchy speculation to the humbug of a virtual impossibility.

So, having pointed out the vices and shortcomings of these very unstable

original elements, permit us now to extol the many virtues of what has actually

been achieved. In a nutshell, nothing short of a miracle…a Cine-miracle if you prefer. Although a triple camera process,

Cinemiracle in a theater massaged with precision the vignetting of its

3-projected panels in perfect registration, with steadiness and a more

homogenized distribution of screen illumination, yielding better overall

definition, image clarity, and, a much greater depth of focus. As an

interesting aside: by the time an audience experienced the film in a theater,

more than nine miles of actual film had passed through these electrically

interlocked projectors.

For this Blu-ray

release, Windjammer’s original

camera negatives have been scanned in with as much loving care as Strohmaier’s

funding would allow. The results are quite miraculous on the whole. Color

fidelity is head and shoulders above its previous home video release; ditto,

for overall image crispness and reproduction of accurately realized film grain.

Occasionally, flesh tones can adopt a slight piggy pink hue. Again, it’s not a

deal breaker. When the elements properly align with minimal age-related damage

and all the technological bells and whistles playing in unison and in harmony,

the resultant image is uncannily Cinerama-esque; augmented by Strohmaier’s

insistence to present virtually all of the Cinerama catalog in the artificially

recreated ‘Smilebox’ Simulation. Although

economically ideal, ‘Smilebox’ is not exactly ‘user friendly’ for those with home

theater projector setups, as there is no way to compensate for the artificially

induced curvature.

It would have

been prudent of Strohmaier to include a flatly scanned in 3-panel recreation

(as Warner Home Video did with their Cinerama release of How The West Was Won; allowing the home video enthusiast to choose the

version to screen, given their circumstances and mode of presentation):

costlier for Strohmaier and Flicker Alley too, and so we will not poo-poo the

decision to only include the ‘Smilebox’

version herein. The original 7-track

audio, featuring an exuberant score by Morton Gould, and some memorable songs

to boot, has been given the utmost care. Many of Windjammer’s songs were recorded live on location. However, when Windjammer’s original soundtrack album

was released, it was an LP re-recording – not the originals, as heard in the

movie. What is here is as it should be, with occasional built-in distortions, but

mostly, yielding extraordinary fidelity for which all Cinerama productions of their

time were duly noted.

Extras assembled

by Strohmaier and his team include a newly expanded making of documentary: The Windjammer Voyage – a Cinemiracle Adventure.

At just under an hour, this is an exceptionally comprehensive account of the film’s

production, culled from vintage interviews with many of the cast and

embellished with rare behind-the-scenes photographic materials never before made

available to the public. We also get The

Reconstruction of Windjammer – another thorough and engrossing look at the

massive undertaking to resurrect Windjammer

from the brink of extinction. The rest of the extras are less impressive,

beginning with the inclusion of the ‘breakdown reel’ (unrestored) and a brief

2010 featurette on the Christian Radich Today,

plus a behind-the-scenes slideshow of images from the production and another,

depicting several of the venues where the picture originally played. I would

have expected an audio commentary too, but no such luck. Bottom line: Windjammer: The Voyage of the Christian

Radich is a one-of-a-kind movie-going experience not to be missed. That the

Cinemiracle process was never again used is a curiosity, considering its

improvements in photographing large-scale 3-panel Cinerama. As for this Blu-ray

reissue: it is a no brainer, highly recommended with caveats as expressed earlier.

Buy and judge accordingly. But prepare to be dazzled nonetheless. This is one

hell of a grand show!

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

3.5

Comments