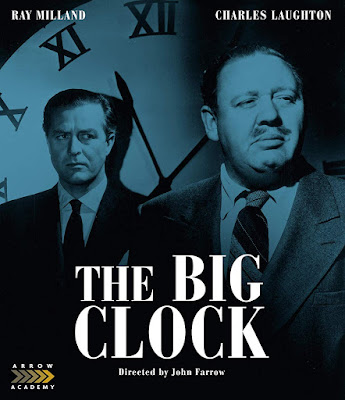

THE BIG CLOCK: Blu-ray (Paramount, 1948) Arrow Academy

John Farrow’s The Big Clock (1948) is a noir thriller,

so efficient, ingenious and, seemingly, effortless, it baffles the mind that

its reputation as a bona fide classic in the pantheon of great noir thrillers

has never materialized. More recently, The

Big Clock has evolved into something of a cult classic with noir enthusiasts.

Still, the public at large has likely never heard of it, despite its pedigree;

based on a compelling crime novel written by poet, novelist and literary

critic, Kenneth Fearing – a very interesting and articulate man. Farrow’s filmic

adaptation, cribbing from a highly sanitized screenplay by Jonathan Latimer, softens

the hard-edged appeal of our hero, George Stroud (partly to placate the

on-screen persona of its star, Ray Milland, but mostly to conform to Hollywood’s

self-governing censorship code. In the novel, Stroud is a notorious lady’s man,

who has no qualm about cheating on his wife and seducing the plaything of his

unscrupulous boss). Latimer’s reworking also cleans up our first impressions of

the ostensible femme fatale, Pauline York (superbly realized by Rita Johnson as

a flaxen-haired and enterprising, but otherwise good-hearted heterosexual gal.

Again, in the novel Pauline is a viperous lesbian with bi-curious tendencies

and a wicked yen for unadulterated revenge). Otherwise, the movie version of The Big Clock remains relatively

faithful to Farrow’s intricate narrative construction, gradually tightening the

yoke around Stroud’s decidedly innocent neck as he engages in a perilous game

of cat and mouse with the disgusting and ever-so-slightly effete megalomaniac,

Earl Janoth (Charles Laughton). On set, Laughton and Milland did not get on,

mostly due to Milland’s overt distaste for homosexuality. Laughton, despite

being ‘married’ to Elsa Lanchester (who also appears in the movie as dotty

artist, Louise Patterson) was gay –

an open ‘secret’ in Hollywood, kept from the general public by this ‘bearded’ alliance and clever studio PR

to ensure Laughton’s reputation would endure long after his career had ended.

Paramount bought

Fearing's novel – a best seller in its day - for a reported $45,000. Initially

Leslie Fenton was assigned to direct; delays on his current project, Saigon (1948) precluding his

participation herein. So, the duties were passed along to John Farrow, whose

career as a screenwriter of some repute dated all the way back to the silent

era and a partnership with Cecil B. DeMille. From here, Farrow’s career only

blossomed, and he worked tirelessly on a spate of successful ‘woman’s pictures’,

as well as the sporadic noir, made at Paramount and RKO. On The

Big Clock, Farrow illustrates his two-fold strengths, as both a writer and

director. Although not credited with any contributions to the screenplay, given

his lengthy tenure as a writer, it is difficult to imagine Farrow having no

influence on Latimer’s authorship. And Latimer, no slouch in the writing

department either, had cut his teeth on fact-based crime articles as a

journalist for the Chicago Herald Examiner and Tribune before turning to pure

fiction in the mid-1930’s. Latimer and Farrow had a mutual admiration that

would see them through a collaboration on ten pictures. The Big Clock was always conceived as a ‘star vehicle’ for Ray

Milland – then, Paramount’s big headliner, and, wielding box office cache that

towered over Laughton’s popularity. It is interesting to note the downward

spiral of Laughton’s own renown, hailed as the greatest living actor of his

generation after his startling transformation into The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939, and ostensibly, the last truly

great performance of his formative career). But in hindsight, Laughton appears

to have fallen between the cracks of Hollywood’s gristmill – billed as a

grotesque, seemingly run out of juicy character parts until his renaissance at

the tail-end of his career, with such startlingly rich and diabolically

delicious performances in Witness for

the Prosecution (1957) and Spartacus

(1960).

The Big Clock sees Laughton doing his damnedest to excel as the

oily, vindictive and disreputable millionaire publisher, Earl Janoth. Janoth

treats his contemporaries with a certain, contemptible disdain as peons, to be

berated, manipulated and even destroyed for his own despicably self-preserving

pleasure. And Laughton, who also suffered in life from his own marginal

contempt for humanity, also seems to be deliberately goading Milland’s

transparent disapproval of his lifestyle, affectionately to place his arm on

his co-star’s shoulder, or infrequently play their scenes together with a certain

‘in your face’ hint of homoeroticism

that greatly enhances the mounting antagonism between Stroud and Janoth as the

former gradually begins to suspect the latter of murder. The Big Clock’s supporting cast is outstanding: Maureen O’Sullivan –

Farrow’s wife, returning to pictures after a 5-year hiatus as Stroud’s devoted significant

other, Georgette; George Macready – usually the villain, herein just a dupe, as

Janoth’s right-hand, Steve Hagen; Henry Morgan, as Janoth’s ruthless masseur/henchman,

Bill Womack, and, Lloyd Corrigan - the red herring and Stroud’s ace-in-the-hole;

Colonel Jefferson Randolph (a.k.a. Inspector McKinley). In the novel, Janoth’s

publishing labyrinth was as much a character as the flesh and blood

counterparts who moved through its corridors. The movie achieves as much of that

impression, thanks to Roland Anderson, Hans Dreier and Albert Nozaki superior

production design (their creation of the uber-sleek and sophisticated lobby and

corporate offices of Janoth’s leviathan are a steel and marble marvel, augmented

by the claustrophobic inner workings of the famed time piece in the book’s

title, rendered as a mechanical wonder in the movie, complete with ominously glowing

control panel and spiral staircase), exquisitely realized through John F. Seitz’s

moodily lit cinematography.

Allegorically, The Big Clock is an indictment of

capitalism: big business’ sway, to have morally corrupted Earl Janoth, enough

to make him commit a cold-blooded murder, then, as callously attempt to frame

anyone - even his ever-devoted wing man, to whom he has already confessed his

crime – merely to save face. Given the

intensity of the central narrative, the picture’s infrequent flights into screwball

comedy, well-timed to allow for the necessary respites between narrow escapes, interjects

humor that, depending on one’s point of view, is either hammy and hilarious, or

a hindrance to the overall arc of psychologically-compelling suspense. Personally,

I think it works wonderfully, as both Laughton and Lanchester are well-acquainted

with the lighter side of their profession and able to deliver the goods with

slick polish. Alas, the brief – and arguably, failed – attempt to make over

Milland’s Stroud and O’Sullivan’s Georgette as the Nick and Nora Charles of the

piece is ever-so-slightly problematic, particularly in a diversionary vignette where

Georgette, having tired of her husband’s chronic inability to follow through on

his promise of a ‘honeymoon’ – departs with their 5-year old son to a remote

cabin, only have Stroud confess to being fired. Georgette’s rather idiotic

reply, as the ‘best news’ of the day as it will realign George’s personal investment

in their marriage, just seems to reek of some strained and illogically devised domesticity.

After composer, Victor

Young’s hard-hitting main title, The Big

Clock opens with a clever pan across the New York skyline, seamlessly wed

to a hanging miniature of the Janoth Publishing building and a camera truck in,

presumably through a window, into a live-action shot of George Stroud skulking

about the darkened interior, narrowly avoiding a security guard and making his

way into the inner workings of the aforementioned ‘time piece.’ His observance

through a window of the heady activity below in the lobby, unseen as yet by the

guards, is accompanied by a voice-over narration, summarizing the fact that a

scant 36 hrs. prior, George Stroud was a ‘family man’ with barely a care in the

world and plans to take his wife, Georgette on their long-overdue honeymoon to

Wheeling, West Virginia. They have been married for 5 years and have a young

son who, due to George’s slavish work ethic, barely knows his father. George is

editor-in-chief of Janoth’s Crimeways Magazine, a post he has occupied with

great respect, though – most recently, whose readership numbers have slipped. The

pompous Janoth calls to order a meeting in his private boardroom, collecting

all of the company’s creative brain trust; then, condescendingly discounting each

and every one of their suggestions – all, except George’s, who has just cracked

a hard-boiled missing person’s case, thanks to his deductive approach to

sniffing out a good ‘crime story’. Alas, Janoth demands George remain in town

to see this effort through to publication. As this will decidedly impugn his vacation

plans, Stroud absolutely refuses to comply and is promptly fired by Janoth.

Having promised

to meet his wife at the train depot by seven o’clock, Stroud instead decides to

partake of a few strong drinks at a nearby fashionable nightclub where he

becomes distracted by Janoth’s glamorous mistress, Pauline York who is also

briefly introduced to Georgette. The wife naturally assumes the worst about her

husband and storms off. Now, Pauline proposes a blackmail scheme against her

lover - Janoth – a means for her to get revenge on the man who ‘done’ her

wrong, but also get George his old job back, decidedly with a bigger salary and

more perks. The plan has merit – superficially, and especially, when one is

drunk. Alas, George has missed his train. Georgette angrily leaves for Wheeling

without him. Rather idiotically, instead of taking the next train out, George

spends the rest of the evening drowning his sorrows with Pauline; the two,

slumming it to a local cut-rate emporium run by an antique dealer (Henri

Letondal), where George out-bargains Louise Patterson, a dotty art ‘collector’,

buying an important missing art treasure for a mere $30. Now, sufficiently inebriated,

George takes Pauline to his favorite watering hole, attended by its proprietor,

Burt (Frank Orth) and introduced to George’s good friend, McKinley. As part of

a bet with Burt, George takes a sundial with a green ribbon around it. This, he

later bequeaths to Pauline, in whose fashionable hotel suite George briefly

crashes with a severe hangover. Stirred from his slumber, after Pauline receives

word Janoth is on his way up, she skillfully ushers George into the hall

moments before the elevator doors part and Janoth emerges, full of venom to

know where she has been all night.

George clearly

sees Janoth, but Janoth only glimpses a shadowy figure hurrying down the rear

stairs. Confronting Pauline with his suspicions, she ruthlessly chides him for

being an ineffectual lover and he, in a fit of rage, bludgeons her to death

with the sundial. Immediately following this impromptu killing, Janoth reverts

to cooler reasoning. He flees the scene of the crime and attends his

right-hand-man, Steve Hagen at his apartment to confess to the murder. Janoth

admits he has no recourse but to go to the police. But Hagen reasons someone

else can be made the scapegoat for his crime; perhaps, the man Janoth briefly

glimpsed, leaving Pauline’s hotel suite. The gears in his warped little brain

working overtime, Janoth decides to use the full resources of Crimeways to unearth

the whereabouts of this man. Realizing he is on the proverbial hook for murder,

George begins to invent a smoke screen to cover his tracks. Briefly, he flies to

West Virginia to reconcile with his wife, but is reeled back to New York to

head Janoth’s investigation. During the

manhunt, George skillfully prevents anyone from identifying him as its target. In

tandem, George also pursues clues to reveal Janoth as Pauline’s killer.

Assembling witnesses at Janoth’s building, George eludes identification, buying

off Louise to paint an abstract that in no way represents his likeness, and

also frightening the antique dealer into a fainting spell. Realizing George is innocent,

Burt and McKinley detain Janoth’s scout on his evidentiary search; McKinley,

later pretending to be a police inspector working on George’s behalf – much to

Janoth’s chagrin.

Discovering his

handkerchief in a cigarette box in Hagen’s office, George realizes he can

intentionally frame Hagen for the murder, thus forcing Hagen to reveal Janoth as

the killer. In the meantime, Janoth sends his henchman, Bill Womack on a

thorough search of the building, already on lockdown. Womack and George engage

in a perilous game of cat and mouse; skulking through the bowels of the

building and eventually winding up inside the inner workings of the big clock.

George momentarily knocks Womack out, hurrying back to Hagen’s offices where

Georgette and McKinley have remained since discovering the handkerchief. George

stalls the elevator in its shaft so Womack cannot follow him. Now, he gathers

Janoth and Hagen together, and with McKinley still faking a police detective, George

accuses Hagen of murdering Pauline. At every turn, George deflates Hagen’s rebuttals

to this accusation, making it appear more and more probable that he actually

committed the crime. At this juncture, Janoth decides to call George’s bluff,

assuring Hagen he will hire the best legal counsel to fight the charge and

exonerate him of the crime. Only now, Hagen lets his loyalties slip. There is only

so much he is willing to do for his boss. Hagen informs everyone Janoth

murdered Pauline and promises to testify to as much in court. Alas, he will

never get the opportunity. Janoth, who has been concealing a pistol in his

pocket, shoots Hagen dead before attempting escape. Having previously stalled

the elevator between floors, thus leaving its shaft wide open, George tries to

get Janoth to stop from fleeing. Unaware of as much, Janoth tumbles down the

shaft several stories to his death. A stunned

Louise openly declares, “It’s him!”

referring to McKinley; ironically, her estranged husband. George takes his wife

by the arm and the two hurry away, presumably to begin their honeymoon at long

last.

The Big Clock is a slick and stylish thriller, immensely aided by the

aforementioned production design of the Janoth Corp. publishing offices, a maze

of monolithic and darkly lit passages and catacombs that allow for the

characters to slip in and out of focus, narrowly to be discovered by one

another. The acting from all concerned is top-notch. Laughton, in particular,

is in very fine form as the obscenely cruel puppet master, holding everyone’s fate

in his meaty palms. Ray Milland’s congenial hero is adequate. Although

top-billed, he takes the proverbial ‘backseat’ throughout most of this story;

upstaged by Lanchester’s scatterbrain, Macready’s unusually sympathetic ‘company

man’, Rita Johnson’s supremely satisfying scorned female, and even, Lloyd

Corrigan, who is obviously having a whale of a good time impersonating a cop. Given

The Big Clock’s box office success its

complete and utter disappearance from the public’s consciousness shortly

thereafter, and total absence, either in theatrical revival or as late-night

fodder on television, seems a terribly sad oversight. Remade in 1987 as the

Kevin Costner thriller, No Way Out,

with political implications, The Big

Clock endures as a minor masterpiece, as yet, rife for a more broad-based

rediscovery.

Arrow Academy’s

Blu-ray release, via their alliance with Universal Home Video, would have

considerable merit, if not for the flubbed 1080p transfer Uni has provided this

third-party distributor. It’s become something of ‘the norm’ at Universal to do

virtually nothing to upgrade old video masters, some made at least four decades

ago, before porting them directly over to hi-def – warts and all. The Big Clock’s 1080p transfer is,

frankly, disappointing. The early reels suffer from way too dark contrast. Just

look at the scene where Milland buys a newspaper in the lobby of Janoth’s

building. The female seller’s face is barely visible. There is also

considerable edge enhancement, built-in flicker, light bleeding on the extreme

right-hand side, and, a small hair caught in the upper right corner. Add to

this, a barrage of streaks, nicks, chips and built-in dirt and well… All of these

age-related anomalies could have – and should have – been corrected digitally

before The Big Clock arrived to

disc. The middle reels of The Big Clock

appear to have been derived from a source that has superior contrast and far

less age-related damage. Nevertheless, film grain never looks indigenous to its

source, instead, adopting a gritty texture that is unbecoming and, in spots,

quite distracting. The audio is 1.0 PCM mono and adequate for this

presentation. Extras are limited to a commentary

by Adrian Martin and two featurettes: the first, by Adrian Wootton, running

nearly a half-hour in reflections on the making of the movie; the second, from

Simon Callow, devoted to Laughton’s participation and reflections on the actor’s

career. We also get the 1948 hour-long Lux Radio dramatization of The Big Clock (also starring Ray Milland)

and an original trailer. Bottom line: while extras are nice – what counts is

the quality of the work being done to ready classic movies like The Big Clock for their hi-def debut. Regrettably,

Universal has not put in the effort here and it shows – miserably, so. Regrets.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

4.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

2.5

EXTRAS

3.5

Comments