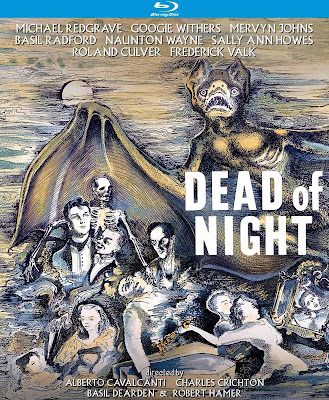

DEAD OF NIGHT: Blu-ray (Ealing Studios, 1945) Kino Lorber

The pinnacle of

British anthology horror, Dead of Night (1945) employs four of Ealing

Studio’s most accomplished directors - Alberto Cavalcanti, Charles Crichton,

Basil Dearden, Robert Hamer – to tell the psychologically complex tale of a man,

driven by a bizarre and haunting déjà vu to rendezvous at a country estate. Dead of Night refrains from bloodshed,

but otherwise delivers blood-curdling results, thanks to its utterly superb

screenplay by John Baines and Angus MacPhail. If only for The Ventriloquist's

Dummy segment, directed by Cavalcanti, then Dead of Night could

already be considered a masterpiece. And, while the remaining vignettes told by

each competing director remain episodic at best – their integration into the

central narrative - merely expressed through fade ins and outs - leaves not a single

moment absent of a sinister and mounting sense of dread to creep us out and permeate

every frame, as the picture builds to its slam-bang wallop. Mervyn Johns’ shell-shocked

architect, Walter Craig, indulged in his notion he has already met the various guests

staying at this country retreat, is regaled with a series of even weirder stories

by its amused patrons, apparently into a good ‘ghost’ story – all except, psychiatrist,

Dr. Van Staaten (Frederick Valk) – the sole skeptic among the group. But Staaten’s

resolve is steadily eroded until this ensemble’s fantasies transgress into reality

and reality mutates into the macabre fulfillment of Craig’s nightmare.

Although Ealing

today is most fondly recalled for their clever and urbane comedies, producer,

Michael Balcon pulled out all the stops for Dead of Night, in hindsight, a

response to the traumatic war years, resulting in a paranoiac psychological

thriller par excellence. Shying away from the affluent, the milieu here is

middle-class, populated by a desirable ensemble of stiff-upper-lipped character

actors. And although Staaten cannot dissuade his cohorts to accept their

unexplained premonitions as mere overactive imagination – a cursed mirror, as

example, leads to attempted murder; a children’s game of hide-and-seek reveals

the ghost of a dead boy strangled nearly a century before by his wicked half-sister

– the supernatural and the surreal herein are allowed their full breadth; the

past and, then, present, intermingling in unexpected ways to build on a far

more evil-inclined and collective hysteria. Despite the picture’s opening disclaimer,

suggesting ‘the events and characters portrayed are fictitious’, and

that ‘any similarity’ is purely ‘coincidental’, the ‘Christmas Party’

sequence, featuring a winsome Sally Anne Howes as Sally O’Hara, the unsuspecting

teen who discovers a tear-stained Francis Kent in a hidden upstairs bedroom of

a great English manor, is actually based on a real incident. Kent, age four, was

found murdered at Road Hill House in 1860. The boy’s sixteen-year-old

half-sister, Constance was later arrested, put on trial and convicted, serving

20 years for murder before emigrating to Australia. There, she remained until

her death - aged 100, only a year shy of the release of Dead of Night. It

would take nearly another 50-years to unravel the crime that shocked England, presenting

two alternate theories; either, Constance had not acted alone, or, in fact, falsely

confessed to protect another member of the family.

Dead of Night is superbly

crafted down to the last detail. If imitation is, as they claim, the cheapest

form of flattery, then Dead of Night owes an ever-so-slight nod to

Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1938) without having to pay for the royalties;

co-stars, Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne as Parratt and Potter – a very thinly

disguised reprise of Charters and Caldicott – the two similarly sport-obsessed

gentlemen, with a genuine verve for wry English humor, who appeared in that

Hitchcock classic. Think of Radford and Naunton as the Brit-based Abbott and

Costello. Indeed, their schtick proved so indelible and amusing to audiences,

they appeared together frequently thereafter, always playing derivations of themselves.

Regrettably, when Dead of Night

found its way to the U.S., it was shorn of its Christmas ghost story and ‘Golfing’

vignette – unhinging the narrative structure and all but crippling the movie’s

eerie dénouement. Dead of Night

also hold a rather dubious distinction of influencing science; cosmologists,

Fred Hoyle, Thomas Gold and Hermann Bondi, inspired by the story’s cyclical

kismet, to develop ‘The Steady State Theory’ of the universe, an

alternative to the more widely embraced ‘Big Bang’.

Only in

retrospect does Dead of Night acquire a sort of Agatha Christie ‘locked

room’ stagecraft quality, adding immensely to its ghoulish time capsule

vintage. Even the weakest among the vignettes, Charles Crichton’s Wodehousian fluff

piece about two golfers competing for the affections of the same woman, or, the

opening segment, about a race car driver who, having narrowly escaped a hellish

wreck, is courted a second time by the specter of death (a vignette loosely based

on E.F. Benson’s 1906 ‘The Bus Conductor’, and later to inspire Rod

Serling’s ‘Twenty-Two’ episode of The Twilight Zone) yield tremendous

charm. Cumulatively, Dead of Night offers even the most jaded contemporary

horror afficinado a chain-rattling/bone-chilling good time. And the complexity

with which the tale has been assembled, continues to astound. The five stories,

featured in flashback, are eventually exposed as intricate pieces to Walter

Craig’s dream – or, actually, a prelude to the architect’s pilgrimage along the

same road already featured in his nightmare. It is a monumental craftsmanship

at play, tightly and graphically unfurled, to tease the brain and make it

question its own mind-warped hallucinations.

Our story beings

with Craig’s arrival at a quaint English country house populated by a dazzling

assortment of British character actors. The estate’s proprietor, Eliot Foley

(Roland Culver) welcomes Craig. In short order, Craig also meets Eliot’s

mother, Mrs. Foley (Mary Merrall), and guests, Joan Cortland (Googie Withers),

Dr. Van Staaten, Sally O’Hara and Hugh Grainger (Antony Baird). Craig knows – or rather - believes he has been

here before, already having met the people to whom he is now being introduced; circumstances

beyond his control that gradually reveal elements of his own violent and

repulsive nightmare. As one by one, the incidents recalled from his nocturnal flight

into fear begin to rattle his nerves, but otherwise intrigue the other house

guests, each setting about to ease Craig’s anxieties by suggesting they too

have been touched by the unexplained and supernatural. Hugh kicks off the

flashbacks, as a retired race car driver who, after a near death experience on

the track, was visited in his hospital room by visions of a Victorian-age

hearse and its unctuous driver (Miles Malleson), brightly declaring “Room,

for one more.” Upon his release from hospital, Hugh prepares to board a

double-decker for the ride home, only to be greeted by the same man, now

driving the bus. Rejecting the fare, Hugh helplessly observes as the bus,

packed with passengers, suffers a malfunction and veers off the road a short

distance ahead of him, toppling over the edge of a bridge, killing all onboard.

While Van

Straaten remains cynical about Hugh’s premonition, chalking it up to mere coincidence,

he entertains Craig’s frayed psyche, after Craig predicts – again, from his dream

– the arrival of a woman, and shortly thereafter, Mrs. Grainger (Judy Kelly)

enters the house, imploring her husband to pay for the waiting taxi. Craig is haunted by the notion he will

eventually be driven to commit an unspeakable act to fulfill his destiny in the

dream. Perhaps a tad unnerved by this, Mrs. Foley encourages young Sally to

return home, but not before she shares her curious tale with the group. During

one snowy eve not so very long ago, while attending a children’s Christmas party

at a great mansion, Sally played a game of ‘sardines’ (a.k.a. hide and seek),

hosted by Jimmy Watson (Michael Allan) – a boy, she is obviously sweet on. As

the other children count down to the moment of discovery, Jimmy finds Sally

lurking behind a curtain in the upstairs hall and suggests a far better place

to hide; the attic, untouched in many years and surely, the very last place

anyone would think to look for her. While navigating through the cobwebbed junk,

Jimmy tells Sally that the house is haunted by the ghost of a young boy strangled

by his sister in 1860. Now, Jimmy tries to kiss Sally. She playfully resists,

and retreats into a hidden side room, whereupon Sally discovers a small boy,

Francis (Barry Ford), sobbing inside a cozily lit nursery. Francis tells Sally

his sister is plotting to kill him. Gingerly comforting the child, Sally puts

Francis to bed, wipes away his tears and promises to sing him to sleep.

Afterward, she hears her friends calling and returns to the group in the main

parlor, only to discover that the boy who was murdered and Francis, the child

in the attic nursery, are one in the same.

Now, Joan relays

her curious tale to the group. For her fiancé, Peter’s (Ralph Michaels)

birthday, Joan bought an antique mirror. Peter is enchanted by the gift until

he begins seeing visions of another room, presumably from the Victorian age,

reflected in its glass. As Joan does not see these same reflections, Peter

begins to suspect he is going mad. To prove his sanity, Joan forces Peter to

confront the mirror with her. Only this time, Peter sees the other room without

her standing at his side. With Joan’s

tender guidance, Peter begins to see the reflection of his own bedroom in the

mirror instead. Believing his odd hallucinations have abated, Peter and Joan

are wed. He loses his fear of the mirror. However, upon returning to the shop

where she bought the cursed relic, Joan is told of its history: owned by a

jealous, wealthy man, crippled in a riding accident. Believing his wife to be

unfaithful, the man strangled her before taking his own life by slitting his

throat in front of the mirror. Anxious to return home, Joan finds Peter staring

into the reflection, enraged at the sight of her. He accuses Joan of having an

affair and begins to strangle her. In desperation, Joan smashes the glass, thus

breaking the spell.

Challenged to

make sense of Joan’s story, Dr. Van Straaten is barely able to offer an explanation

when Craig nervously announces he is leaving before the rest of his nightmare

can come true. Van Straaten implores Craig to remain and confront his fears,

and Foley, plying them both with drink, begins a yarn of his own. In this flashback we meet, golf-obsessed

George Parratt (Basil Radford) and Larry Potter (Naunton Wayne); deadly rivals

on the green, but best friends off it. Alas, these fair-weathers are put to a

test with the arrival of Mary Lee (Peggy Bryan) who favors each with her

romantic overtures. Unable to choose between them, Mary manages to make both

men miserable, utterly wrecking their concentration and love of the sport. To

settle the score, George suggests they play one final round – the loser, to

agree to leave for good. George wins this wager, though only by cheating. Larry

accepts defeat and to George’s horror, strolls calmly into the nearby lake

where he is drowned. Sometime later, Larry’s spirit returns, threatening to

haunt George into an early grave unless he gives Mary up. Begrudgingly, George

agrees to these terms. Only Larry now claims to have forgotten ‘the code’ to

re-enter Heaven. Desperate to rid himself of Larry’s ghost, George’s search

ends with his own disappearance, whereupon Larry enters George’s bedchamber

where Mary is waiting, grateful to take his place.

The Golfer’s Tale

is by far the most light-hearted and amusing of the vignettes, immediately

followed by Dead of Night’s most macabre outing. Breaking with doctor/patient

privilege, Van Straaten recalls his most notorious case; that of renown

ventriloquist, Maxwell Frere (Michael Redgrave) and his cheeky dummy, Hugo

Fitch (voiced by John McGuire). Catching Maxwell’s act, American ventriloquist,

Sylvester Kee (Hartley Power) is ‘invited’ by Hugo to go backstage. In

Maxwell's absence, Hugo suggests he and Sylvester team up. Assuming this is

part of Maxwell's act, Sylvester is impressed. But Maxwell genuinely fears

Sylvester will take him up on Hugo's offer. Not long thereafter, Sylvester

witnesses a drunken Maxwell involved in a brawl in the hotel bar. Sylvester

helps Maxwell to his room, leaving Hugo propped against the bed. Later that

evening, Maxwell bursts into Sylvester's room, demanding to know what has

become of Hugo. Sylvester protests, but is astonished when Hugo is found in his

room. Now, Maxwell shoots Sylvester twice, though not fatally. Attended by Van

Straaten in his prison cell, Maxwell is reunited with Hugo. Once Van Straaten

leaves, Hugo taunts Maxwell. Driven insane, Maxwell smothers the dummy before

stamping its head to pieces on the floor. Sent to an asylum, Maxwell is visited by

Sylvester, who has recovered from his wounds. Only now, the voice which greets

him is not Maxwell’s, but Hugo’s.

As Van Straaten concludes

his story, he inadvertently breaks his glasses, fulfilling the last of Craig's

prophecies. Night falls and the other guests retire to their bedrooms, just

like in Craig’s nightmare. Left alone with the psychiatrist, Craig is compelled

to strangle him. Suffering from delirium, Craig relives portions of all the

other vignettes, swirling about his mind. The pandemonium is diffused when

Craig is stirred from slumber by his wife (Renee Gadd). So, it really has been

just a bad dream. The telephone is ringing. It is Eliot Foley, inviting Craig

to a weekend in the country for an appraisal of his property. As yet unaware

his déjà vu is about to begin all over again, Craig dresses with confidence and

embarks upon the journey to the country estate. Alas, as he approaches the

house, he develops a queasy unease. Oh, no! - the nightmare is beginning all over again.

Dead of Night was decidedly a

departure for Ealing Studios; producer, Michael Balcon’s ambitious venture to

break free from wartime rationing that had effectively relegated Ealing as a production

house of B-budgeted documentary picture-making. Balcon likely refrained from any

hint that Dead of Night was a horror movie, as Britain’s governing board

of censorship would have slapped the dreaded ‘H’ restricting audience

attendance. So, Dead of Night took its loftier aim at telling a good

ole-fashioned ghost story – and not just one – wrapped in the enigma of a

fateful supernatural melodrama. Viewed

today, Dead of Night has lost none of its devastating charm as a

psychological thriller. Interestingly, while Balcon borrowed prestige from

noted authors, H.G. Wells, and, E.F. Benson in the ‘original story’ writing

credits, the movie’s most memorable skits (The Haunted Mirror, Ventriloquist’s

Dummy, and, Christmas Party) were actually hand-crafted by screenwriters,

John Baines and Angus MacPhail. Today, with all the cheap imitations to have

followed it, much of Dead of Night plays with a time-weathered

familiarity that was distinctly absent at the time of the picture’s premiere.

Even so, it’s the professionalism of the piece that continues to shine through;

Stanley Pavey and Douglas Slocombe’s luminous cinematography, and, Michael Relph’s

exquisite art direction, contributing to the unsettling and very English atmosphere.

The anthology movie is perhaps the toughest nut to crack, as its episodic

nature practically ensures disjointed storytelling. What is of paramount

importance then, is the ‘linking’ narrative, necessary to create cohesion

between these otherwise disparate vignettes. And herein, lies the true

greatness of Dead of Night; Craig’s déjà vu odyssey, weaving in and out

of these various ghost stories with an ominous premonition that miraculously is

connected, in some form or another, by a fatal kismet, certain to be revived at

the picture’s final fade out – the real beginning of the end for Craig’s chronic

visitation from these supernatural forces.

Dead of Night arrives on

Blu-ray state’s side via Kino Lorber. While the picture has certainly been

through the proverbial ringer over the decades, this new Blu, while light years

ahead of anything previously seen on home video, still falls short of

expectations. Kino’s marketing denotes the transfer has been culled from a 4K ‘restoration’.

To my eyes, I believe Kino has confused ‘restoration’ with elements having been

scanned in at 4K ‘resolution’, but with minimal restorative efforts otherwise

applied. Retained in this image, minor gate weave, occasionally edge

enhancement, and, a lot of age-related dirt and scratches that occasionally

distract. Framed in its proper 1.37:1, the overall image quality does take a

quantum leap forward in overall sharpness and fine detail, with a light

smattering of film grain looking very indigenous to its source. We applaud the

effort, certainly. But the overall image is still very rough around the edges

and with added digital anomalies that detract from our viewing pleasure. Worse,

the 2.0 DTS mono audio is a queer mix of grating and scratchy distortions

and/or intermittently muffled, garbling the dialogue to the point where it is

inaudible. Personally, I found the audio

extremely problematic and, on the whole, one of the worst efforts yet put forth

to stabilize a vintage recording. Film historian, Tim Lucas provides a

comprehensive audio commentary, discussing the discrepancies between the U.S.

and U.K. release. But the big surprise here, is Remembering Dead of Night

– 75 minutes of discussion with college lecturer, Keith Johnston, critic, Danny

Leigh, author and critic, Kim Newman, Matthew Sweet, writer-actor, Reece

Shearsmith, critic, Jonathan Romney, and director, John Landis. Difficult to

call this one a ‘documentary’ – more like, a series of ‘talking head’ conversations

loosely strung together with only one or two inserts from the movie itself,

accompanied by zero archival footage, stills, poster art, etc. Bottom line: Dead

of Night is a classic deserving of better. Only a monumental restoration

will do. This isn’t it. Visually, the Blu-ray is adequate, though just. From an

audio perspective, it is well below par. Regrets.

FILM RATING (out

of 5 – 5 being the best)

4.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

3

EXTRAS

3

Comments