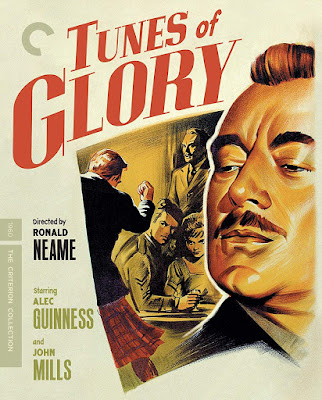

TUNES OF GLORY: Blu-ray (UA/Lopert, 1960) Criterion

An extraordinary piece of cinematic ‘stagecraft’ based on James Kennaway’s

best-selling novel, and rumored to have been Alfred Hitchcock’s favorite movie

of all time, director, Ronald Neame’s Tunes of Glory (1960) remains a

sobering and sad-eyed reflection on the weight, as well as the responsibility

that comes with valor. Men of decision are hard to come by. Moreover, they are

not without their flaws – the latter truth usually excised from the

Hollywood-ized notions of masculine flag-waving fortitude. And Kennaway’s

screenplay, like his novel, clearly illustrates the disconnect between valor

and honor – the former, viewed through the steely-eyed victories of ego run

amok, the latter, bereft in deliberately seeking the valor for its own sake. Best here, to remember an old Roman adage, one

used in the welcoming of its warriors back home after battle - “Thou art

only a man.” Kennaway’s ruminations on regimented life in the Scottish

military pits the formidable vigor of two of England’s greatest actors – Sir Alec

Guinness (as the flaming-haired and fiery-tempered Major Jock

Sinclair) and Sir John Mills (the more scholarly Lieutenant Colonel Basil

Barrow) – in a battle royale, one where the spoils this time do not go

to the victor, but also to prematurely pulverize the hard-won merits and

virtues of both men into dust. Interesting to contemplate what the movie might

have been had Guinness and Mills merely accepted Neame’s original plan to cast

them opposite; Guinness, the first to realize the role of Barrow was decidedly

not to his liking. Indeed, Guinness had already played similarly ‘by the

book’, as Colonel Nicholson in the 1957 Oscar-winner, The Bridge on the

River Kwai. And certainly, on the heels of that memorable performance, viewing

Guinness herein as the bombastic and carousing officer, rather insidiously to

insight the other to take his own life is a jolt to the system; not the least,

because Guinness – the consummate actor – appears to have been to the bully’s

mantle born. His Scottish brogue is perfection, and, the explosive personality

with which he infuses Sinclair, shatters all previous perceptions of Sir Guinness

as a gentleman’s officer.

Guinness’ role is undeniably the flashier part. Mills, in no small way, has

the uphill climb to achieve similar on-screen stature as Barrow, a role that

repeatedly refrains from competing for the spotlight. That Mills, a superb

actor in his own right, is never straight-jacketed, ostensibly by playing ‘the lesser’,

is – in fact – its own miracle. And what a very fine performance it remains; Mills,

to gingerly reveal Barrow’s inner torture, his mounting insecurities,

exacerbated by Sinclair’s erroneous assumption, that the officer assigned to

replace him is but a wan ghost flower of himself, even a sop to be publicly humiliated

over and over again as a mere figure of fun. Mills’ take on Barrow is uniquely

situated between valor and honor – the proverbial rock and its hard place,

eventually to squeeze out his personal integrity and thereupon force him into a

corner from whence suicide is the only sweet escape. Tunes of Glory is

also noteworthy for the debut of Susannah York as Sinclair’s daughter, Morag –

desperately in love with one of the pipers, Corporal Ian Fraser (played with

appropriate masculine verve by handsome and dashing John Frazer). Think it’s

easy to look like a man’s man in a kilt, toting bagpipes? Try it sometime! York, whose undeniably beauty could

nevertheless convey such winsome and wide-eyed innocence, would see her own film

career fast-tracked after Tunes of Glory; afforded the lead in The

Greengage Summer (1961) and toying with Albert Finney’s fickle heart in the

Oscar-winning, Tom Jones (1963) – role in a movie she nearly turned down.

Other classic performances soon followed, including supporting parts in A

Man for All Seasons (1966), Battle of Britain, and, an Oscar-nod for

her role in They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (both movies made and

released 1969). In 1980, critic, Michael Billington effectively summarized York’s

lasting appeal thus, her “…greatest achievement… to escape the pigeonholing

that is the curse of her profession and to overcome the perception of her as

the flaxen-haired beauty of 1960’s British movies. In her richly fulfilled

later career, she proved that she was a real actor of extraordinary emotional

range, not just a movie star.”

Born in Auchterarder, Perthshire, there was nothing about James Kennaway’s

early and unassuming middle-class upbringing to infer a prolific career as a

writer awaited him on the horizon. In life it has – at least - been suggested, Kennaway’s

hard-drinking and wild charm ultimately contributed to his untimely death in

1968, felled by a fatal heart attack and subsequent car crash just before Christmas

– age, 40. Most certainly, Kennaway’s predilection for strong drink put a

strain on his marriage, though it clung together until his death. Tunes of

Glory, first published in 1956, was Kennaway’s debut novel. It also remains

his best-known, likely due to its translation to the movies – also, perhaps,

because enough of the novel’s spirit remains intact, thanks to Kennaway’s contributions

on the screenplay. Personally, I have always felt his follow-up, Household

Ghosts, published in 1961, an infinitely more striking masterwork; an

intimate deconstruction of a Scottish family’s frayed emotions, later to be

adapted for the stage and film – though less successfully as Country Dance

(1969). In reviewing both novels again for the writing of this review, as well

as perusing the pages of his final work, the novella ‘Silence’, published

posthumously in 1972, the staggering depth of Kennaway’s clairvoyance in social

critique is what rivets us to his every word committed to paper. ‘Page-turner’

might very well have been coined for Kennaway’s prose. His characters breathe

and come rushing forth as few then, and certainly fewer still today have from ‘modern

literature’.

Tunes of Glory was shot at Shepperton Studios in London. Indeed, the

original plan was to use Stirling Castle in Scotland, the Regimental

Headquarters of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders as the film’s primary

location. Regrettably, the commanding officer at Stirling, having already given

his consent – so long as the shoot did not disrupt daily exercises – withdrew it

almost immediately, after seeing a copy of Kennaway’s book with lurid cover art

on a paperback stand. Although Neame was eventually allowed to photograph the

path leading up to the castle for establishing shots under the main titles, a

hanging miniature had to be created to alter the rooftops so as to render its

likeness unrecognizable at a glance. As for the rest – the grand halls,

cobblestone and snowy courtyards, etc.: these were realized by Wilfred

Shingleton’s superb production design, moodily lit and photographed by Arthur

Ibbetson, and augmented by a sparse, though memorable underscore by Malcolm

Arnold. For familiarity’s sake, Neame gathered close creative personnel with

whom he had already worked. With Guinness, Neame had done The Horse's Mouth

(1958), while other alumni, Kay Walsh (as Barrow’s one-time paramour, and

cheeky music-hall performer, Mary Titterington), Ibbetson and editor, Anne V.

Coates had all contributed to various projects in the past.

Tunes of Glory begins with the snowy and windswept approach of Morag

Sinclair to Stirling Castle under the main titles. We retreat to the relative

warmth and revelry inside the Battalion Officers’ mess, Jock and his cronies

enjoying the perks of being enlisted men after the war. Major Sinclair – an

aging boozer/baller, is celebrating his bittersweet final hours as the

regiment’s commanding officer. Alas, one gets the distinct impression Sinclair,

who took over after the battalion's colonel was killed in action during the

North African campaign in WWII, has governed here mostly by fear and favoritism

– a noxious combination to those not part of his inner circle. Considered an

asset during the latter half of the war, Jock is now to be replaced by

Lieutenant Colonel Basil Barrow, whom Brigade HQ regards as more appropriate

for peacetime. Sinclair, while jovial indulging in strong drink and rather

crude opinions of the man who will shortly take over, is, in fact, deeply wounded

by his enforced obsolescence. Indeed, he regards Barrow as nothing better than

a book-learned and weak-kneed fossil, surely to soften and quaintly countrify

the rugged masculinity of his men. As such, a quiet animosity immediately stirs

after Barrow arrives early – and right in the middle of Jock’s whirling jig

with his men.

Momentarily recovering from this rather gaudy display of Scotch-soaked

revelry, Barrow and Sinclair cordially exchange their respective military backgrounds;

Sinclair, taking great pride in his accomplishments as an enlisted bandsman who

clawed his way through the ranks, winning the Military Medal and Distinguished

Service Order during the war. By contrast, Barrow hailed from Oxford

University, his ancestors, colonels before him. Serving only one year with the

regiment before being posted to ‘special duties’, Barrow is viewed by Sinclair

has having led a charmed life as a ‘stupid wee man’. Thus, when Sinclair

rather proudly tells of an incident in Barlinnie Prison, briefly detained on a

charge of being drunk and disorderly, Barrow reticently countermands with a

story of his own imprisonment in a Japanese POW camp – clearly, the more

harrowing of the two experiences. Sinclair contemptuously presupposes Barrow

received preferential treatment as an officer under the articles of war when,

in fact, Barrow endured hellish mistreatment at the hands of the enemy with permanent

psychological scars. While all of this comparative chest-thumping is going on,

Morag engages in secretive rendezvous with Piper Frazer. The couple are

desperately in love, but sincerely fear reprisals if Sinclair finds them out.

Aware of their burgeoning romance, but as cautious of revealing too much, Pipe

Major Maclean (Duncan MacRae) encourages prudence on Morag’s part. She is, at

first, incensed by his liberties taken to offer her sound advice, but then

realizes the kindly and doting Maclean, who really acts more like a surrogate

father to her, only has her best interests at heart.

Meanwhile, Barrow wastes no time passing orders to impose his own brand

of discipline. Contentious among these edicts is the instruction all officers take

Highland dancing lessons to reel in their habitual raucousness in more formal

mixed company. Obliging the newly instated rule, Sinclair repeatedly insists on

adopting his own lack of finesse to the art of the dance. While a good deal of

the men, still loyal to Sinclair, revel in his defiance, Captain Jimmy Cairns

(Gordon Scott) is empathetic to Barrow’s desire to ‘smarten up’ the regiment. Alas,

Barrow’s first exercise in instituting a new outlook between the regiment and

the townspeople, a cordial cocktail party, is a disaster when Sinclair

encourages the men to cast off their newly acquired culture in favor of a rambunctious

display on the dance floor. Outraged, Mills calls a halt to the music and, in

fact, the party, sending everyone home and retiring to his quarters in abject

humiliation; a decision to further damage his credibility with the men. Amused

and immensely satisfied he had won this decisive victory over this new

commanding officer, Sinclair retires for a little détente with Mary Titterington,

a former flame and music hall performer who no longer shares his romantic

interests. Unable to convince Mary to partake of his desire, the inebriated

Sinclair retreats to a local watering hole where he inadvertently discovers Piper

Fraser and his daughter sharing a pint together. Accosting Fraser in public,

Sinclair is put on official notice and suspended from duties.

His imminent court-martial, however, is repeatedly delayed as various

factions of the regiment offer Barrow their opinions on how best to proceed.

Barrow is, at first, staunchly determined Sinclair should suffer the slings and

arrows of his own actions and face the court-martial with dignity. Alas, Barrow

is also deeply aware this view is highly unpopular with the men, most of whom

believe the matter should be quietly swept under the proverbial rug and neatly

forgotten. Perhaps for the first time in life, Sinclair genuinely fears for his

future – the battalion, ostensibly, all that he has left in life. Under

ill-advisement, even from his closest allies, Barrow stands down and drops the

court-martial, a decision Barrow promises to back with his full support from

now on, but in fact, almost immediately dismisses as another triumph over

Barrow, whom he further regards as a push-over. Retreating to Mary with his

bombastic good fortune, Sinclair discovers her in the arms Major Charles Scott (Dennis

Scott), whom he readily despises. Scott, however, is unapologetic about his low

opinion of Sinclair, suggesting all he has really achieved is the abject

humiliation of a basically good officer, head and shoulders above the rest, and

certainly more worthy of the post than Sinclair ever was.

Devastated by Sinclair’s betrayal, and further to have alienated himself,

even from the officers who formerly supported him, Barrow goes upstairs. While

Sinclair and his revelers continue to laugh and carry on at Barrow’s expense,

Barrow commits suicide in the showers by shooting himself in the head. The

gunshot sobers Sinclair, who attends the fallen Barrow and pronounces him dead.

Realizing he is fully to blame, Sinclair calls the officers to a meeting the

next afternoon, announcing his plans for a formal funeral usually afforded only

to field marshals, complete with a cortege through the town in which all the ‘tunes

of glory’ will be played by the pipers. When it is pointed out how lop-sided these

plans are to the circumstances, especially given Barrow’s death was suicide,

Sinclair brutally insists it was not suicide, but murder. He tells everyone

that, with the exception of the colonel's adjutant, Jimmy Cairns, he – Sinclair - is

the murderer, the other senior officers who followed his lead, all of them - accomplices.

Overwhelmed by his grief, Sinclair suffers a sincere collapse and is escorted

from the barracks while the officers and men salute as he passes by.

Tunes of Glory is an exceptional entertainment. James Kennaway’s screenplay

lost to Richard Brook’s for Elmer Gantry – the only Oscar-nomination the

picture received state’s side, with BAFTA nominating ‘Tunes’ for Best

Picture, Best British Film, Best British Screenplay and Best Actor nods to both

Guinness and Mills. Mills, in fact, walked away with the Venice Film Festival’s

Best Actor honors, while the picture was named ‘Best Foreign Film of the

year’ by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Movies are oft judged by such

accolades received, or worse, by those never-to-be won. Yet, Tunes of Glory

– despite its dearth in documented accolades, is a compelling and time-honored

tale of chivalry in all its various forms. Alec Guinness and John Mills deliver

peerless performances that, grouped within each actor’s body of work, never pales,

though queerly continues to be overlooked. Let us be fair, here. Both Guinness and Mills

were such accomplished talents of their ilk and generation, bringing their

respective, bountiful, and seemingly bottomless wellspring of professional

talents to bear on movies that will live forever, that to single out any one

performance and rate it as their personal best is to draw undue insult to the

remaining balance of their bodies of work. Even though she appears for less

than 15-minutes, one can definitely see why Susannah York became such a big

star after Tunes of Glory. She exudes a passionate, yet subtle warmth, as

illuminating to the character she plays as to her own character emanating from

within. Even at a glance – which is about all we get to see of her in this

movie - York is radiant and gorgeous.

Tunes of Glory arrives on Blu-ray via Criterion in a 4K digital

restoration conducted last year by AMPAS, The Film Foundation, Janus Films and

MoMA with funding from the George Lucas Family Foundation. Employing 35mm

Eastman Color original camera negatives, the image herein is decidedly warmer

than its tired old DVD incarnation released by Criterion 15 years earlier.

Alas, the elements never crisp up, and, intermittently toggle between relative

stability and exaggerated amounts of grain, amplified and occasionally

distracting in hi-def. Nevertheless, this presentation has a film-like quality,

even if it heavily favors ruddy flesh tones, and an overall cooler palette with

generally solid contrast. I was a tad

disappointed. The anticipated refinement from a 4K scan dumbed down to 1080p is

lacking here. Criterion offers up a PCM mono track that is basically flat.

Given this is a dialogue-driven movie, a forgivable shortcoming. Not so forgivable: Criterion offers us

nothing new in the way of extras. Virtually everything here was a part of Criterion’s

DVD release from 2004: nearly a half-hour with Ronald Neame, an audio-only

interview with John Mills, and a video interview with Alec Guinness. I love these

extras. But would it have broken the bank for Criterion to produce one or two

new ‘reflection’ pieces for this hi-def reissue? I mean, they did as much for

their hi-def release of Valley of the Dolls (1967). Bottom line: Tunes

of Glory is exceptional film-making with two of the greatest actors of any

generation offering definitive proof of their supremacy among the stars. The

Blu-ray, while improving on the DVD (how could it not?) is, alas, not perfect.

Otherwise, this one comes very highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

5+

VIDEO/AUDIO

3.5

EXTRAS

3

Comments