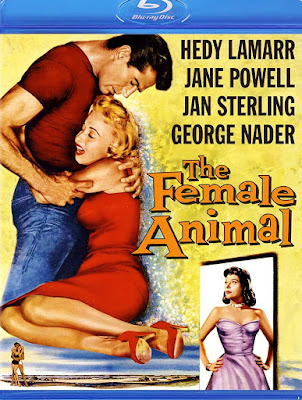

THE FEMALE ANIMAL: Blu-ray (Universal-International, 1958) Kino Lorber

Yet another reworking on the Hollywood ‘hags to bitches’ story, director, Harry Keller’s The Female Animal (1958) is not an altogether deft little programmer, despite headlining two top-tier talents from the golden age - Hedy Lamarr and Jane Powell – the former, decidedly gone to seed, the latter, desperate to be rid of her squeaky clean ‘nice girl’ image. In its day, The Female Animal played as the top-half of a double bill for Universal with (wait for it) Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil – an irrefutable masterpiece, and comparatively, to be ranked as pure gold next to this box office tin. The Female Animal was, in fact, Lamarr’s final bow in pictures, the once luminous beauty, not so radiant anymore. Time has proven Lamarr’s real talents – and brains, for that matter – lay elsewhere; an inventor, whose mind was constantly a whirl with innovative ideas, and, whose contributions on frequency-hopping spread spectrum technology remain as relevant today – perhaps, even more so – the precursor to Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. In her prime, Lamarr’s beauty suffered from the taint of eroticism, thanks to her appearance in 1933’s Ecstasy – a German movie in which she not only appeared in the raw, but also simulated masturbation and an orgasm. Yeow! Arriving in Hollywood to entice MGM’s raja, L.B. Mayer into a lucrative movie contract, Lamarr was circumspect but frank about her involvement in this Euro-snuff fluff. “Did you look good?” Mayer inquired. “Of course,” Lamarr admitted with an air of confidence. “Then everything’s alright!”

In hindsight, Hedy Lamarr’s entire movie career is hermetically

sealed with that rather vacuous expectation she could dazzle a room, simply by entering

it – an elusive quality, Lamarr possessed in spades, even as a child. And thus,

the pictures she made, ranged from quaintly romantic, if slightly careworn, little

programmers (1941’s Come Live With Me, 1942’s White Cargo) to the

occasional megawatt standout, where she was inevitably relegated to decorous

background while the other stars shone (1940’s Boom Town, 1942’s Ziegfeld

Girl). By the end of the forties, Lamarr’s popularity had waned. So, by 1958,

it was practically nonexistent. Curiously, a similar fate had befallen her

co-star, Jane Powell – more recently billed as an effervescent soprano, or MGM’s

answer to Deanna Durbin – but now, struggling to find her niche in the

fast-fading days of the Hollywood musical. Presently, 91-yrs. young, Powell’s appeal in The

Female Animal is wafer thin – cast as the unloved daughter of a Hollywood

legend, too self-involved and self-destructive for her own good, but certain to

be ‘reformed’ by the love of a good man. It is a thankless part, yet

practically to rate the Sarah Bernhardt Award compared to third-billed Jan Sterling,

as the platinum-haired, venomous denizen of moral depravity. In a role

originally intended for straight-lace John Gavin, fifties’ beef-cake, George

Nader endured some hellish body-waxing to show off his sinewy and muscled frame,

sporting very tight and very high-cut shorts. Despite the picture’s title, The

Female Animal is really an extended opportunity for Nader to flex, preen

and otherwise splay and stretch himself across the elongated proportions of the

Cinemascope frame as raven-haired eye-candy, albeit, with a heart and stick-figure’s

soul.

The Female Animal is a very odd, and occasionally lame duck; Robert Hill’s lumbering screenplay (based on a story by Albert Zugsmith), endeavoring to be the sort of Hollywood grotesque a la Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950), but otherwise winding up as just a feather-weight, and occasionally laughably bad farce – this one about another middle-aged actress refusing to age gracefully. Indeed, screen siren, Vanessa Windsor (Lamarr) is a woman unable to come to terms with having an adult daughter she tries to keep secret from her adoring fans while chasing after men half her age. Vanessa’s ravenous desire to remain young forever leads her into the arms of film extra, Chris Farley (Nader), who moonlights as something of a gigolo to make ends meet. Having rescued Vanessa from a falling arch lamp on the set of their latest picture, and, to have sustained an injury to his arm that stirs her ‘motherly’ intuition, Vanessa lures Chris back to her Malibu beach house for a private dinner. Attempting a seduction, Vanessa strikes out when she received a frantic phone call, informing that her daughter, Penny (Powell) has fallen ill. Rushing away, Vanessa quickly unearths Penny, bitter and spoiled to a fault, is not sick at all – rather, drunk. Endeavoring to shake some sense into the girl, Vanessa becomes hostile and Penny spitefully accuses her mother of adopting her for mere publicity – an allegation not entirely without merit, and for which Penny receives a well-deserved slap across the cheek.

Returning to Chris, Vanessa offers him a caretaker’s job at the beach house. Although he has been considering a picture for his old pal, Hank Galvez (Jerry Paris) – to be shot in Mexico – the job pays nothing, and Chris, desperate for money, accepts Vanessa’s offer instead. Rather predictably, the two become lovers shortly thereafter. For a while, Chris does not mind his status as a kept man; that is, until in inadvertently bumps into the ravenous man-trap, Lily Frayne (Sterling), who would sincerely prefer to have him for her own. Lily finds Chris’ lack of curiosity in her rather insulting, more so when he takes a minor chivalrous interest in an inebriated Penny, who is being brutalized by her date du jour. The prerequisite ‘fight scene’ ensues, Chris rescuing and driving Penny back to the beach house. Although she has clearly been there before, she indicates no familiarity with the place to Chris, nor does she explain to him she is, in fact, Vanessa’s daughter. Unable to talk some sense into Penny, Chris instead carries her into the shower, fully clothed, to sober her up. At first enraged, Penny comes around and seduces Chris with a kiss. Chris continues seeing Penny on the sly while publicly seen as Vanessa’s flashy arm-charm male escort, much to Lily’s chagrin.

Vanessa is very generous, buying her lover a half-dozen suits. Only now, Chris is having second thoughts. As Hank’s offer to go to Mexico is still good, Chris reveals to Penny he intends to fly out as soon as possible. Instead, she springs a surprise on him – she is Vanessa’s daughter. Outraged – more so, as Penny is morbidly pleased with herself and threatens to expose their affair to her mother, Chris takes Penny over his knee and gives her a good thrashing. After a few wounded tears, Chris and Penny come to an understanding. Vanessa becomes jealous after seeing Chris talking to Penny. In reply, Vanessa inveigle Chris in a proposal of marriage, telephoning Hedda Hopper with her good news and thus, forcing Chris’ hand. Sometime later, Vanessa also makes the announcement to Penny – testing her reaction. Startled her lover will soon be her stepfather, Penny is disgusted by this turn of events. Only now, Chris has acquired enough guts to call off the wedding. And although he leaves Penny’s name out of his reasons for leaving, Vanessa begins to suspect Chris is in love with someone else. Preparing for her ‘big scene’ in the latest picture shooting, Vanessa is quietly confronted by Penny, who lowers the boom on her mother’s delusions by revealing she is the one Chris actually loves. Humiliated, Vanessa attempts suicide by throwing herself off a narrow precipice into a swirling man-made lake on the movie set – a stunt to have been performed by her double. Chris heroically dives in and rescues Vanessa. Only now, having survived near death, Vanessa has had a sincere change of heart. She confides in Chris; their love affair would not have endured. Vanessa further promotes Chris’ happiness with Penny. As the young couple departs, the camera comes in for a close-up on Vanessa’s bittersweet and tear-stained face.

The Female Animal is not a film noir, as it is often billed, but a seedy little backstage melodrama, tracing the sadly incoherent lifestyle of a fast-fading screen queen, never again to be considered Hollywood’s cutest little trick in shoe-leather. It is rather tragic to see Hedy Lamarr – one of the irrefutable beauties back in her day – played for a has-been, age-41. Jane Powell, 14-yrs Lamarr’s junior, feigns a more adult role, all bundled in fake bitterness, presumably instilled by Vanessa’s maternal neglect. Alas, Powell comes off as just another spoiled rich girl with an axe to grind. Although George Nader is given the plum part as the high-minded muscle boy/toy, he does the absolutely least with it. Let us be fair, but real here, to suggest Nader’s strength was not in his prowess as an actor. It also might have something to do with the Pasadena-native’s homosexuality, a tad too transparent here – virtually zero romantic chemistry with either of these two women to which his alter ego is supposedly bound. In the mid-fifties, Nader was snatched up by Universal for his beach bod and clean-shaven good looks; the studio, then, acquiring studs like paperclips – by the handful. Nader became a good friend to Rock Hudson, and, although he kept his sexual preferences hidden, the celluloid closet in full swing throughout the mid-fifties and sixties, Nader would continue his lifestyle with a meaningful life-long partner in Mark Miller, with whom he remained until Miller’s death in 2002. Viewed today, The Female Animal is an awkward blend of the traditional Hollywood backstory, the seedy exposé, and, the supposedly sex-charged fifties’ phenomenon for salacious male/female melodramas, to have reached its apotheosis one year earlier with Peyton Place, only to implode a decade later with 1967’s Valley of the Dolls. That The Female Animal never goes ‘all the way’ either in exploring this mother/daughter/gigolo lover’s triangle (how could it, with Hollywood’s self-governing production code heavily breathing down director, Keller’s back), is forgivable. That Hill’s screenplay should instead be incapable of disentangling all these disparate plot points into one coherent story is not.

The Female Animal arrives on Blu-ray via Kino Lorber’s alliance with Universal Home Video in a B&W 1080p transfer, not without its issues. For starters, Uni has done practically nothing to upgrade the video master. The Universal-International logo and opening scenes are marred by a considerable amount of age-related damage – chips, nicks, scratches, and, some built-in video noise and edge effects. Transitional dissolves and fades suffer from unnaturally amplified grain levels and there are one or two instances of curious moiré patterns. Although age-related damage is present elsewhere, it mostly settles down after the main titles, and, for long stretches thereafter, resulting in a relatively pleasing image that, nevertheless, leans to a more video-processed look, with grain homogenized by the application of DNR. It’s not quite to the egregious levels we have come to anticipate on some other Uni product released via Kino (Mirage, 1965, immediately comes to mind). There is some good solid detail too, particularly in close-up. Nevertheless, The Female Animal does not look anything like it ought – or, in fact, did, when released theatrically. The DTS 1.0 mono audio is adequate for this primarily dialogue-driven movie. Historian, David DeValle’s audio commentary is very comprehensive and entertaining. Bottom line: The Female Animal is a middling effort from all concerned. DeValle’s commentary is time better spent than on the movie itself. The picture has some wonderful B&W cinematography from Russell Metty to recommend it, but that’s about all. This Blu-ray is a shaky B- effort. Judge and buy accordingly.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

2.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

3

EXTRAS

1

Comments