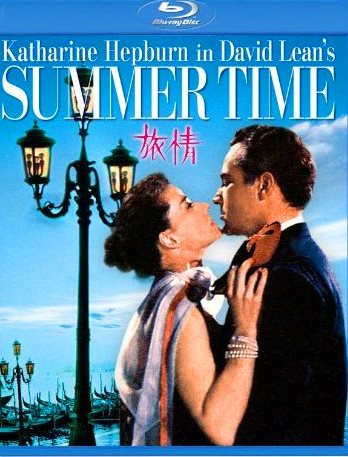

SUMMERTIME: Blu-ray (United Artists, 1955) Twin/Paramount Home Video

David Lean’s intermediate film,

that is, the one to straddle the chasm between his ‘little gem’ class of

intimate English dramas and drawing room comedies, and, point the way to his

later period as the purveyor of peerless epics built on a gargantuan scale, was

Summertime (1955). With Venice’s timeless allure, sumptuously

photographed by the great cinematographer, Jack Hildyard, the cloying tale of a

spinsterish secretary on her first big holiday away from home, who finds an

unlikely and bittersweet romance with an aging Lothario, became the stuff of

richly rewarding, if slightly travelogue-heavy escapism. Venice is undeniably

the interloper into this middle-aged love affair without the traditional happy

ending. Here, Lean was perhaps drawing on his own Brief Encounter (1945)

for inspiration, and, of course, Arthur Laurents’ 1952 Broadway show, The

Time of the Cuckoo, specifically written for Shirley Booth, who actually

won a Tony for it. Alas, in adapting the play for the screen, Lean was to

quickly become dissatisfied with the material as written. His complicity on the

project became assured after producer, Hal B. Wallis’ ambitions to acquire the

rights fell through and Ilya Lopert instead became the custodian of the

material with sincere plans to hire Booth and director, Anatole Litvak to

partake of the exercise. Wallis wanted

Katharine Hepburn instead. Lean would concur with this casting choice later on,

replacing Ezio Pinza with Rossano Brazzi as his male lead. “They called and

said that David Lean was going to direct it,” Hepburn would later

reminisce, “…and would I be ... They didn't need to finish that sentence. I

certainly would be interested in anything that David Lean was going to direct.”

Even then, there were rocky bumps to overcome in Summertime’s

gestation, Lean feverishly working with associate producer, Norman Spencer and

writers, Donald Ogden Stewart and S.N. Behrman to improve upon the material.

Ultimately, novelist, H.E. Bates would be brought in to polish the script and,

along with Lean, receive sole writing credit on a story that bore no earthly

resemblance to the Broadway show, though arguably, it improved upon Laurents’

usually immaculate prose and construction.

Summertime is a

deliciously uncompromising parable for those enduring the absence of love in

youth, the unanticipated discovery of it in middle-age, and the friction to

occur when aged prejudices collide with an unquenchable romantic yearning to

uncover something miraculous in the every day. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Lean is

unabashedly sentimental here, imbued with his newfound and encapsulating

romance of celluloid for the city itself, lingering along its claustrophobic

alleys and taking long photographic respites to show off Venice to its most

sublimely gorgeous effect, becoming deeply involved with every sensualist

moment as only a rank tourist, intoxicated by first impressions, can experience

in any foreign port of call. Still, Lean’s impressions of Venice remain exceptionally

sustaining, only somewhat because of his ability to make us see it all through

his hawk-eyed camera lens, supplanted by Hepburn’s willingness to be immersed

in the city’s queer amalgam of grit and glamour, lavishly appointed piazzas

contrasted with half-lit, cobble-stoned byways, cluttered in clothes lines

lazily dangling overhead. At the start of Jane Hudson’s vacation, Lean lays

these merry contradictions at Hepburn’s feet – literally. Jane’s dewy-eyed

gazes into the canal are suddenly interrupted by layers of rubbish raining down

from an upstairs window, unceremoniously dumped into the waters just ahead.

Equally, the Pensione Fiorini is a fascinating blend of shadow and light; its’

heavily draped lobby and shuttered sitting rooms giving way to golden sun-lit

balconies and bridges overlooking water-lined arteries, teeming with taxiing

gondolas.

Summertime would be

nothing at all without Katharine Hepburn’s heartbreakingly sincere central performance.

Hepburn, by 1955, was finely honed in her repertoire of seemingly

tough-as-nails heroines, stricken with an air of vulnerability, gradually

unearthed from a hidden wellspring where still waters invariably run much

deeper than anticipated. I have often

viewed Summertime as the quintessential Hepburn performance, perhaps

because it shies away from the austere confidence Hepburn so capably exuded in

practically every other role. The tears just seem real here, the wounded heart

too, yearning for something more resilient, yet unable to entirely commit to its

spirit of true love, or, in Summertime’s case – love on its own terms,

as it comes - frankly imperfect, ethereally fleeting and ultimately,

heartrending. It is Hepburn’s own tangible loneliness, rather than that of her

alter ego, Jane Hudson, that lends genuine ballast to this unapologetically

adult and unvarnished grand amour. Summertime’s courting protocol may

have considerably dated since. But as a character study in the reawakening of a

spinster’s starved heart – too long lain dormant beneath her sense of pride, it

remains genuinely affecting and effective. As a vehicle for Hepburn, it is

perfection par excellence. Summertime is the perfect movie

for…well…summer time. Lean’s notions of Italy, or rather, a stodgy American’s

open-hearted reluctance to entirely give in to its clichéd Technicolor

impressions, develops with a lithe flair for tenderness, rather than melodrama:

all to the good, as Hepburn occasionally is prone to gilding this lily.

In the turmoil that was to become Summertime

behind the scenes, many names were bandied about for the much sought-after

starring roles, including Ingrid Bergman, presumably to be reunited with

Roberto Rossellini, then Olivia De Havilland and actor/director, Vittorio De

Sica as the swarthy Italian lover, Renato de Rossi (the part ultimately going

to Rossano Brazzi instead). Summertime is duly noted as one of the first

major films to be shot entirely on location, Venice’s government officials,

with undue pressure applied by the local gondolieri, resisting Lean’s request

to immortalize the city on celluloid, as the unique requirements of catering to

a movie crew would necessitate whole portions of its waterlogged byways and

bridges shut down during the peak tourist season. Ultimately, United Artists

agreed to a generous stipend to help fund the restoration of St. Mark's

Basilica, prominently featured herein. Lean was also ordered by the Patriarch

of Venice to refrain from photographing shorts skirts, strapless dresses, and,

bare arms in and around the city’s holy sites, a prelude to the battles he

would face with the Catholic League of Decency.

Lean, who could be rather exacting

and precise in his level of expectation, was also to encounter minor opposition

from Katharine Hepburn regarding one of the more light-hearted scenes where

Jane Hudson takes an unexpected tumble into the canal. Hepburn, a stickler

where her own health was concerned, at first refused to perform the stunt

herself. Lean implored her to reconsider, as, at such close range, it would be

virtually impossible to successfully mask a double. Hepburn eventually relented

and took every precaution to guard against infection from the notoriously

polluted waterways, applying protective lotions all over her body and even

antiseptic unguents on a small cut on one of her fingers. Afterward, she

immediately bathed and gargled with disinfectant. Nevertheless, Hepburn would

forever rue the hour she had given in to this request, contracting a rare form

of conjunctivitis that would continue to plague her for the remainder of her

life. As production wrapped, Lean elected to rent a summer house, having fallen

in love with the culture and the city in tandem. He was not altogether

impressed by boycotts imposed by both Production Code Administration head,

Geoffrey Shurlock, who ordered trims made – approximately eighteen feet of film

– to distill the more obvious implications of adultery, nor The National

Catholic Legion of Decency’s demand to excise a line of telling dialogue after

Jane and Renato ostensibly consummate their affair. Nevertheless, Lean

complied. There was little else he could do. Even so, Summertime was

given a B-rating, a designation ascribed to movies considered ‘morally

objectionable in part’, in today’s rating system where anything pretty much

goes, a thoroughly laughable ascription to say the least.

Summertime is arguably tame,

Hepburn’s nervous forty-year-old virgin brought to heel at the altar of her

more sensual and worldly man of sophistication. However, maturing Jane Hudson’s

outlook comes with unanticipated reprisals on both sides of the sex/morality

continuum. Her lover is presumably well-versed in his proclivity, wooing

wealthy tourists, himself swayed by Jane’s captivating, if transparent naiveté.

Ironically, it is Jane’s unanticipated surrender to these raptures of

love-making that both liberate and cut short their burgeoning affair. At

precisely the moment when it appears at least probable for Jane to reconcile

her prudish sense of straight-laced propriety with Renato’s matter-of-fact

approach to love and love-making, her desires to throw caution to the wind crumble.

Her resolve hardens, or rather, gets detoured into an inescapable retreat from

the fray. Jane will leave Venice with her memories preserved, though,

ostensibly, stirred by her yoke of fear (i.e. Catholic guilt) to deny herself a

singular moment of distinctly adult happiness. In some ways, Summertime

is conspicuously more about the quixotic misfortune that derives from

discovering a great winter passion too late to make a difference. The light

touches of comedy, particularly in scenes between Jane and the irrepressible

urchin, Mauro (Gaetano Autiero), are feathered between the more ‘serious’

melodrama. Example: landlady, Signora Fiorini (Isa Miranda) is having a tryst

with American painter, Eddie Yaeger (Darrin McGavin) right under his wife,

Phyl’s (Mari Aldon) nose. But these vignettes take a backseat to the Teutonic

determination of our dyed in the wool spinster, invariably leading to a lot of

midlife crises of conscience and grave disappointments on both sides.

Summertime begins with

Jane Hudson’s arrival by train to Venice, accompanied by an unnamed Englishman

(André Morell) who has been sharing her compartment. He admits Venice is many

things to many people. Some, find it oppressively crowded and noisy, while most

immediately fall under its romantic spell. Jane, an unprepossessing middle-aged

elementary school secretary from Akron, Ohio will not be disappointed. Inundated

by the cluttered sights and sounds of this chaotic port, bustled onto a waiting

vaporetto (water taxi) traversing the narrow canals on route to the Pensione

Fiorini, Jane is invigorated by her first impressions of the city. These get

watered down by her luck of chance meeting with fellow Americans, Lloyd

(MacDonald Parke) and Edith (Jane Rose) McIlhenny. At the hotel, Jane is taken

under the wing of Signora Fiorini (Isa Miranda), a widow who has transformed

her late husband’s manor into a profitable pensione since World War II. Also on

the property are painter, Eddie Yaeger (Darren McGavin) and his wife, Phyl

(Mari Aldon). Almost immediately, Jane realizes she is the oddball of the group.

The couples go off together to partake of Venice’s pleasures, leaving Jane to

wallow mostly in self-pity and mounting despair. Her grief is interrupted by an

unlikely friendship with Mauro, a ten-year-old urchin who cajoles Jane into

offering him one of her American cigarettes. When all else fails, Jane relies

on Mauro to show her the sights.

Later in the evening, Jane explores

the Piazza San Marco in all its flourish of tourists and regulars, tasting the

wine and taking in the atmosphere of this spectacular outdoor venue. Alas, the

sight of so many couples gingerly locked in each other’s embrace leaves Jane

slightly depressed. Nerves get the better of her after she realizes she is

being watched by a man seated only a few tables away. Unable to acknowledge his

presence in any meaningful way, Jane hurriedly returns to the pensione and

cries into her pillow. It seems she has come a long way for nothing. Venice is

for lovers – not loners. The following afternoon, with Mauro’s help, Jane

stumbles upon the same man again. This time, he introduces himself as Renato de

Rossi – the proprietor of a shop selling vintage glassware. De Rossi reminds

Jane of their previous night’s unrequited introduction and is even bold enough

to suggest she has come to his shop today in search of him rather than souvenirs.

Jane rectifies these misguided notions by pointing out to de Rossi she has

merely been drawn to a red glass goblet advertised in his window. She offers to

purchase it for the full retail price. But de Rossi encourages Jane to

reconsider and shows her how to employ various bartering techniques to enhance

her shopping experiences elsewhere in the city, thus saving her some money

besides. Jane is grateful for the information, but rather standoffish. Hoping

to coax another rendezvous, Renato offers to go in search of a matching goblet on

Jane’s behalf. It may be just a ruse to learn her address in town. But Jane

willingly complies.

That evening, Jane waits in the

Piazza San Marco, hoping to see Renato again. She turns up the chair next to

her and sets out an extra cup to keep other potential suitors at bay. But the

plan backfires when Renato sees the chair and believes he is not welcome to sit

down either. The next day, Jane deliberately goes to the shop under the pretext

of making another inquiry about the red goblet. Only this time the shop’s young

assistant, Vito (Jeremy Spencer) is there. Disappointed, Jane decides to

immortalize the location with her movie camera. Inadvertently, she stumbles and

falls into the canal, her camera rescued at the last possible moment by Mauro’s

quick thinking. Jane is humiliated and begs Mauro to accompany her back to the

pensione. Learning of the incident, Renato attends Jane in the comfort of the

pensione’s sitting room. But she is as aloof as before, and worse – quite

unwilling to acknowledge the sparks of a mutual attraction brewing between

them. Renato does everything to coax Jane from her heart-sore cocoon. Alas, her

insular resolve is amplified when the McIlhennys return from a shopping

expedition on the island of Murano where they have just purchased a matching

set of red goblets virtually identical to the one Jane bought at Renato’s shop.

Believing Renato lied to her about the authenticity of her own glassware,

perhaps a prelude to other lies yet to be told her, Jane becomes rather cruel

in her admonishments after the McIlhennys have retired to their room.

“I don't know

what your experience has been with American tourists,” Jane insists,

in a deliberate attempt to humiliate Renato. He is unshaken by her inference he

is something of a roving gigolo, trolling for easy marks, replying “My

experience has been that tourists have more experience than I.” One of the

most astute and rewarding aspects of Summertime is its clear-eyed

dialogue on the topic of sex – generally, a taboo and thus ignored or playfully

skirted around with elements of the screwball comedy thrown in to lighten the

severity in its address in American movies from this same period. Summertime

resists humor here, however, and Rossano Brazzi’s delivery of the following

lines is tinged with an air of masculine ego.

“I am a man and

you are a woman. But you say, ‘It's wrong...’ You are like a hungry child who's

been given ravioli to eat. ‘No,’ you say, ‘I want beefsteak.’ My dear girl, you

are hungry. Eat the ravioli.”

“I'm not that

hungry,” Jane admits.

“You Americans

get so disturbed about sex,” Renato sternly suggests.

“We don't take

it lightly,” Jane admits with steeliness.

“Take it. Don't

talk it!” Renato swats back.

Unable to reason her way out of the

obvious attraction between them, Jane reluctantly agrees to attend an outdoor

concert in the piazza. Renato is amused

when she selects a gardenia from among the flowers offered to her by a local street

vendor. Jane confides, the blossom has sentimental value, a glowing reminder of

a long-ago love affair that, for reasons never entirely disclosed, ended

uneventfully. Renato escorts Jane back to the pensione. She resists his gentle

advances, but suddenly – and rather unexpectedly – kisses him full on the

mouth, whispering “I love you” before rushing off to bed alone. To

inaugurate her newfound independence as a woman in love, the next day Jane

treats herself to a local spa, gets her hair done and buying a new, and rather

un-anticipatedly racy strapless black dress with red shoes and gossamer shawl

to match. Having agreed to meet Renato at the piazza at eight, Jane’s initial

excitement to show off her ‘new look’ is thwarted when Vito arrives in his

place to inform Jane, Renato will be a little late, owing to the fact Vito’s

younger sister has taken ill with heat exhaustion. Assuming the children are

Renato’s niece and nephew, Jane is stunned when Vito explains he is Renato’s son,

and furthermore, Renato already has a wife. Believing herself to have been a

fool for lesser things, Jane tells Vito to tell his father she will not wait

for him. Jane then, retreats to a nearby bar to drown her sorrows. There, she

is surprised by a tearful Phyl, who confides that her own marriage is on the

rocks.

Upon returning to the pensione,

still disillusioned by what she perceives as Renato’s betrayal, Jane stumbles

upon Eddie and Signora Fiorini – the other woman in Phyl’s lover’s triangle.

Deeply upset to think she might have played a similar role in Renato’s marriage

Jane is uncompromising when Renato unexpectedly shows up to defend his position

- explaining that his marriage is an unhappy one – and has been for some time. He

no longer lives at home with his wife, despite the fact they are not divorced.

When Jane draws a parallel between their amorous misbehavior she has already

judged as a sin, and those indiscretions indulged by Eddie and Signora Fiorini,

Renato suggests their relationship is no one’s business but theirs. Renato

accuses Jane of being prudish. She desires love as much as he does. If only she

would admit as much – at least, to herself – and get on with the business of

living, instead of judging everyone else as illicit and cheap, she too might

discover the happiness she seeks. Unable to debate her way out with logic, Jane

allows Renato to steer them through a romantic dinner, playfully indulging in

the animated wind-up toys being sold by a local vendor. Afterward, Renato

casually lures Jane to his apartment, the inference of their consummated affair

reflected in a display of fireworks. In what can be described as a case of

‘great minds thinking alike’, Lean has either borrowed or blatantly ripped off

this moment from Hitchcock’s superbly staged seduction between Cary Grant’s

suave jewel thief and Grace Kelly’s glacial ice princess in To Catch a Thief,

released earlier this same year).

For the briefest of wrinkles in

time, Jane is over the moon in love. She allows Renato to plan the rest of her

vacation. He charters a boat and takes Jane to Burano, the island where the

rainbow fell - a colorful hamlet where they can be quietly alone and passionate

together, lying in the tall grasses, enjoying majestic sunsets and daydreaming

of a life Jane suddenly realizes can never be hers for the asking. Her sense of

propriety supersedes the passion she has given into and known only too briefly.

Thus, Jane elects to cut her vacation short, quietly packing her things and

preparing for what will be her last rendezvous with Renato at the piazza the

next morning. He is stunned by her decision to go away just as things were

beginning to look promising. But Jane is resolute, telling Renato all her life

she has never known when to leave a party. It is time to leave this one before

each of them realize she has outstayed her welcome and the intensity of their

passion has cooled or morphed into inevitable regrets. Jane begs Renato not to

accompany her to the train depot, but secretly longs for him to see her off. At

first, it appears as though Renato has obliged this request. But then, as the

train pulls out of station, Jane sees Renato racing toward the open window of

her car with a gardenia. Regrettably, the train is moving too fast for Renato

to catch up, and the last impression of the only man Jane Hudson has ever

genuinely loved is that of a heroic Lochinvar, proudly holding up his flower

she can cherish and remember only as a symbol of their blissful moment in time

together.

Summertime is a

quintessentially guileless meditation on middle-aged sexual relationships. Moreover, the movie broke new ground in 1955,

denying the governing boards of film censorship their usual satisfaction of

having such ‘indiscretions’ punishable in the end. Arguably, Jane’s premature

surrender of her own happiness is punishment enough – at least, for Lean, who

had covered some of the same territory in the aforementioned Brief Encounter.

Whereas that movie ends with a strained reconciliation of the marriage being

tested, Summertime’s finale involves no such contrition. Renato is not

going back to his wife, even if he has lost the only woman to whom his heart

belongs. Perhaps the only person truly

dissatisfied with these bittersweet results was playwright, Arthur Laurents who

later confided, “David Lean was morose, cold, detached; much more interested

in Katharine Hepburn than in The Time of the Cuckoo. The name of a character is

very important to me. I go through endless candidates, searching for the one

name that is the character; that suggests the character to a stranger. Now, the

screenplay was credited to H. E. Bates, a first-rate English novelist…but it

should have been credited to K. Hepburn and D. Lean; true believers that stars

can do anything they want - even write. In this aspect of the movie business,

they were unoriginal.”

Indeed, Lean and his producers,

Michael Korda and Ilya Lopert were to have their way with Laurents’ prose,

tearing into his structure and dialogue and greatly altering everything to suit

their own agenda. Laurents had wittily titled his play to infer a parallel

between the cuckoo bird – a migratory visitant, proclaiming its summer time

arrival as to mark the season of love – with Jane Hudson’s first appearance in

this foreign setting. Korda reasoned the movie-going public would have little

to zero knowledge of the cuckoo’s migration patterns and elected with Lopert to

change the title to ‘Summertime’: in Britain, to Summertime

Madness. Nevertheless, the end result affirmed the merits of all their

meddling. Summertime was both a critical and box office success to the

tune of a then impressive $2 million. Today, it survives as a lushly

photographed, exquisitely acted and nostalgic testimony to love itself,

imperfect and touching and thoroughly satisfying, plucking ever so gingerly at

the life chords of all pining romantics seeking truth, perspective and meaning

from the incongruities of love.

Summertime has been

notoriously absent on Blu-ray, except for this rather butchered release from

Japanese distributor, Twin - curiously advertised as being distributed by

Paramount Home Video. Aside: I find this rather hard to believe. We will stick

to the info on the packaging, although exactly how Paramount might have

acquired a United Artist picture is beyond me. This disc is region free,

meaning it will play anywhere in the world. Small consolation, that. Right off,

I am going to pray Criterion’s recent announcement of finally getting around to

remastering Summertime for Blu-ray in North America is going to yield better

results than this! One thing is for certain. Criterion’s announcement it will

retain the 1.37.1 aspect ratio of an open matte when Summertime was originally

shown theatrically in 1.75:1 has prematurely managed to ruffle a lot of purist’s

feathers. While the open matte/full frame reveals considerably more of the

luscious Venetian landscapes, it also contains a glaring amount of head room

that continues to look awkwardly unnatural.

Color fidelity on this Blu-ray is

rather impressive on the whole. Reds, rustic browns, sun-burnt oranges and vibrant

greens pop off the screen. But there are several glaring examples of

misalignment of the 3-strip Technicolor negative, resulting in some modestly

disturbing halos. Mercifully, these instances are few and far between. More

disconcerting is the lack of general cleanup. Dot crawl, dirt, scratches, and

even the occasionally color-timing cue are present. A few scenes appear to

suffer from untoward digital tinkering, harsh edge effects cropping up now and

then. Also, the film’s indigenous grain looks slightly digitized, particularly

in scenes shot at night. There is also a considerable amount of gate weave and

one overhead shot of the Piazza San Marco at night where the various elements

used to assemble the matte are highly unstable and wobble all over the place.

Overall, this is a middling effort at best and a complete fail in today’s

advanced film preservation/restoration, since it neither preserves nor even

makes the effort to adhere to the original film maker’s intent in its

mis-framing of the image. The audio is adequate, though just – occasionally

sounding quite scratchy, particularly, Alessandro Cicognini’s score. Summertime

has not been given its due in hi-def. The film deserves far better than this

and we will sincerely champion it gets exactly what it needs in the near

future. Bottom line: pass and be glad that you did.

FILM RATING (out

of 5 – 5 being the best)

4.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

2.5

EXTRAS

0

Comments