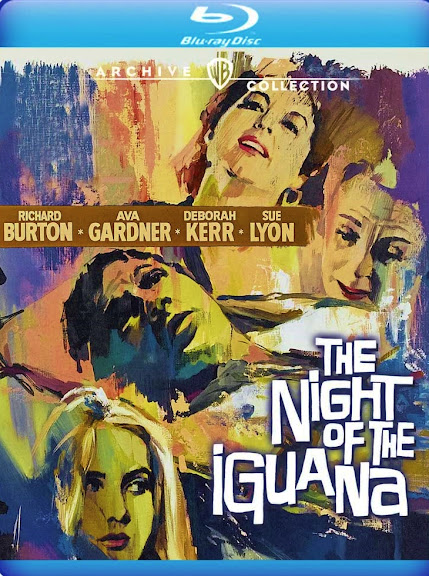

THE NIGHT OF THE IGUANA: Blu-ray (MGM-Seven Arts, 1964) Warner Archive

Leave it to director, John Huston

to hatch a bit of mayhem to launch the shoot of The Night of the Iguana (1964);

his exquisitely tawdry big screen adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ scathing melodrama,

invested in original sin and the three women from varied backgrounds who draw a

disgraced man of the cloth closer to his truest self. The play, a sizable smash

on Broadway, running 316 performances, added to William’s already formidable

reputation, with a cast headlined by Bette Davis as the uninhibited Maxine

Faulk. Davis had hoped – mostly against

hope – to be considered to reprise this role on celluloid. Alas, it was a part

heavily sought by virtually every other actress in Hollywood. And Huston had his own notions about who

should play this highly sexualized free spirit – intuitive and, as it turned

out, right on the money. In hindsight, Huston was picking not only from the

very best Hollywood had to offer, but according to type. Determined to create a

potent ice-breaker to divert from the recent Elizabeth Taylor/Richard Burton contra

ante in Rome ( to have scandalized two Hollywood marriages - Taylor’s to pop singer,

Eddie Fisher and Burton’s to his long-suffering Sybil), and all but laid waste

to Joseph L. Mankewicz’s costly epic, Cleopatra (1963), and also, to quell

the international paparazzi, still in their all-consuming feeding frenzy, swirling

about Taylor’s behind-the-scenes

presence on set - as though it might generate another mega-kilowatt round

of rumormongering - Huston had gold-plated Derringers made and bullets engraved

with each member of his cast’s name. These were handed out at the party to kick

off location work in Puerto Vallarta, then, a sleepy and remote little hamlet,

ideally suited to Huston’s need to be secretive and far removed from the

scrutiny of the studio.

Evidently, everyone got a kick out

of Huston’s gesture, the guns – mercifully - never used, and, the mood on set

immediately turning jovial and remaining in high spirits throughout the

production, fraught with anything but the sort of insidious and grating

friction evoked by the characters in the play. However, there were a few

moments to illustrate otherwise. Burton, apparently unaware a bodyguard had

been hired to keep the press at bay, had a minor tantrum aboard the tiny plane

carrying everyone to this remote retreat after discovering a burly Mexican

seated across from him, toting a gun. Elizabeth Taylor’s presence throughout

the shoot was mostly welcomed by cast and crew, despite being initially frowned

upon by Burton, who knew all too well from their prior working relationship in

Rome what a ‘distraction’ she could be. Still, the filming of The Night of

the Iguana ignited considerable controversy, the local newspaper, Siempre,

declaring “Our children are being introduced to sex, booze, drugs, vice, and

carnal bestiality by the garbage from the United States: gangsters,

nymphomaniacs, heroin-taking blondes.” A nearby Catholic convent weighed

in, protesting Taylor, as neither she nor Burton were yet divorced from their

respective spouses and thus, by all religious conventions, ‘living in sin’,

thus threatening to contaminate the social mores of the locals while blatantly

thumbing their noses at the Catholic Church and God.

All this backstory is, however, prelude

to the fact The Night of the Iguana is a masterpiece, made at a time

when screen censorship was steadily being tested and eroded by more ambitious

filmmakers, eager to show audiences the uglier side of humanity. Indeed, the

timing could not have been better for Tennessee Williams, whose Southern Gothic

stagecraft frequently reveled in the delusional and self-destructive nature of

humanity at large and the desecration of carefully plotted public reputations.

Williams actually based his 1961 dramatization on a short story written in

1948, along the way, to flesh out two tertiary characters – Hannah Jelkes and

her grandfather – creating an entire subplot to carry his third act. But the real inspiration for the short story

had come from a fortuitous vacation Williams had taken in 1940 to Acapulco.

Perhaps it was the heat – frequently blamed by Williams for the inertia guests

showed toward virtually all world events taking place outside their sweaty

little enclave, but Williams became utterly fascinated by the seemingly

accepted ennui of the locals, and, even more compelled to write about its

peripatetic toxicity, poisoning the blood of an entire culture. Aside: I often

wonder, if he had lived, what Tennessee Williams would have made of our

present-day, navel-gazing cohort.

John Huston had admired the play, The

Night of the Iguana, approaching Seven Arts as an independent to fund a

movie version for him to direct and quite unaware producer, Ray Stark was

already firmly committed to hiring Huston to do just that. As Huston’s plans to

shoot on location took shape in rather dense and remote jungle vegetation,

necessitating virtually all of Maxine’s mountaintop retreat to be built from

scratch and to spec, Huston’s ace in the hole in getting the project green lit,

and then, achieving unprecedented and tamper-free autonomy from the studio, was

MGM’s own sad implosion. Repeatedly rocked by corporate drama in the boardroom,

Metro’s ‘close-knit’ control over independents like Huston had taken a backseat

to ever-increasing clashes between executives vying for power back at Culver City

to steady an already badly foundering ship. With no real mogul to steer the

ship, Metro’s track record for producing smash hit entertainment was spotty at

best. Unhinged by the loss of founding father, L.B. Mayer, and reeling from the

government’s decision to splinter all Hollywood kingdoms of their autocratic governance

as the sole purveyors of mass entertainment, MGM proved too vast and much too

unwieldy an empire to command from the position of a mere bean-counter. Worse –

the studio seemed incapable of making a truly ‘big picture’ without forcing

some of the most respected names in the industry to fall into line and abide by

their rules. Some, like directors, Stanley Kubrick and David Lean resisted such

interference, the undiluted purity of their resultant masterworks made under

Metro’s banner (2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968 and Doctor Zhivago,

1965 respectively) reflecting their staunchly personal commitments, even under

the yoke and duress of this potentially damaging tug-o-war for creative control.

To some extent, John Huston took

full advantage of Metro’s lapse in keeping close tabs, rigorously rehearsing

his actors and technicians behind the camera to capture his vision on celluloid

while still remaining within the studio’s allotted time frame and budget. In

viewing The Night of the Iguana today, one is immediately awestruck by

Huston’s incredible telescopic focus and discipline. He seems particularly

engaged, delivering a riveting drama, both swift and assured, moving at a

breakneck pace with plenty of raw and uninhibited emotion, yet miraculously,

never rushed, clumsy or wanting to maintain its high-stakes tension. Better

still, Huston handpicked his cast from a superb assortment of heavy hitters,

some, decidedly going – or even, slightly gone – to seed, while others were on

the upswing and extremely eager to chomp at the bit and do their best work for

him. “It was a mystery then, you

see,” Huston would later comment while reminiscing about Puerto Vallarta

and Banderas Bay, “Just someplace barely on the map and not looking to be

discovered by anyone anytime soon. When

we came, we had to build everything from scratch. I set up camp like a general

going into battle. But none of what we needed was there. Dirt roads: every time

it rained you didn’t dare drive a truckload of equipment up there or get stuck

in the mud trying. Damn hot too. But unspoiled – innocent. That’s what I liked

most. You could get lost up there. People need places to get lost sometimes.

The boys from the press came along and with their flashbulbs turned it into a

goddamn Disneyland. Makes me sad and wanting for the way it was before we

came.”

The Night of the

Iguana was a real boost to the local economy, the subsequent ‘fall out’ from

transforming such a remote location into a world-class resort destination,

generating ‘the boom’ that continues to keep this area prosperous with tourist

trade to this very day. Huston had been in love with Mexico ever since 1929,

when he navigated his private yacht up the Pacific Coast. In the interim,

virtually nothing about Mexico had changed. Huston’s love affair with the place

and its indigenous peoples had only grown riper with the passage of time.

Indeed, one of Huston’s insistences was to shoot in Mismaloya, a tropical oasis

with nooks and crannies virtually untouched by human hands. By this juncture in

his career, Huston had sincerely tired of the North American lifestyle, the

artifice in making movies too. “You can’t create paradise lost on a sound

stage,” he mused, “Much less on a back lot. There’s no uncertainty to

it. No danger. No spark of life, which is what Tennessee’s plays are always

about. You can’t fake that. You have to feel your way through it, stumbling,

going with your gut reaction to being there – and location helps actors do this

better than any manufactured prop or painted sky.”

From the onset, Puerto Vallarta

appealed to Huston – also, to Elizabeth Taylor – precisely because of its

uncharted rugged exoticism and remoteness. Half-way around the world, Huston’s

carousal into experimentation, not having to worry about an impromptu visit

from the money men, generated a genuine sense of living in the moment. This

carried through into a highly palpable feeling of urgency in the finished film.

As for Taylor, few in town – apart from the press – knew, or cared, who she

was. This suited Taylor just fine. But it was really Huston who remained in his

‘element’ throughout this shoot. Tennessee Williams had set his short story in

Acapulco, circa 1940. And if Huston harbored the intensity of a creative genius

already having fallen in love with Mexico, his friendship with producer, Ray

Stark – who immediately considered Huston the eminence gris in all things

Mexican – could also appreciate Huston’s alliance with Guillermo Wulff, an

engineer from Mexico City, whose list of influential contacts in the government

included even the country’s President, Adolfo López Mateos. This alliance

afforded Huston unprecedented access to virtually any of the nation’s areas and

assets he desired. Huston was well

respected by the locals too, having shot a good deal of his 1948 classic, The

Treasure of the Sierra Madre in Durango and Tampico, one of the first

location shoots to take full advantage of this starkly rugged countryside.

Either way, Huston would have given

his right arm to direct The Night of the Iguana, simply to experience

Mexico again. “It’s one of the countries I like best in the world,” he

confided, “Besides, location is just like an actor. It gives something to a

picture, you know, envelops it in an atmosphere.” Huston held both Stark

and Williams in very high regard, but particularly Tennessee, whom he

considered the foremost living playwright of his generation. In adapting Williams’ play for the screen,

Huston, together with screenwriter, Anthony Vellier, was careful not to tamper

(much) with Williams’ explosive and sexually-charged dialogue, only the overall

construction of the piece, and even then, simply for the purposes of ‘opening

up’ the stage-bound material to accommodate the infinitely more vast expanses

of the movie screen. Meanwhile, Wulff set about convincing Huston Mismaloya, a

beach south of Puerto Vallarta, would be ideal to make the picture… ‘ideal’,

being a relative term. For although Mismaloya satisfied virtually all of

Huston’s criteria in terms of capturing the isolation and slightly careworn

seediness integral to the plot, it was also a virtually untapped oasis with

zero luxuries to offer a visiting film crew - not even electricity or indoor plumbing!

In retrospect, the creative

symbiosis between Tennessee Williams and John Huston seems preordained. Both

men were ardent, though clear-eyed cynics, scarred by life but able to

clear-cut past human foibles that often seem too great, or perhaps, merely too

obvious to be challenged and exposed in articulate and meaningful ways.

Succinctly, both Williams and Huston shared an affinity for the morally

downtrodden, spectacularly fallen from grace. In William’s case, these figures

of moral turpitude were usually men, nearly consumed by self-pity and stifling

guilt – dreamers too, actually, raked over the coals by a reality threatening

on all sides, purposely meant as the plague to destructively scour their

palettes, even as they teeter on the brink with seemingly no means of escape.

Such is the case for the recently defrocked Episcopal cleric, Reverend Lawrence

T. Shannon (played with a miraculous semi-tragic self-reproach by Richard

Burton). Here is a man driven half-mad by an indiscretion with a female

parishioner, mostly recently made to feel unclean about his antiseptic

friendship with a precocious – if slightly spoiled – rich girl (Sue Lyons,

fresh from playing the debaucherously delicious Lolita for Stanley

Kubrick in 1962). Lyon’s variation of that character herein, as the ironically

named, Charlotte Goodall, creates general havoc for both Shannon and

Charlotte’s stern chaperone - the closeted lesbian, Judith Fellowes played with

venom by Grayson Hall.

Huston could, perhaps, recognize a

bit of his wilder, though arguably ‘former’ self in Shannon, moreover, in

Burton’s emotionally raped portrait of his fictional counterpart - God’s

lonely, tortured soul, yearning for purity and simplicity in his life, yet ever-doomed

to fall back on more puerile and primal urges to seduce, and willingly allow

himself to be seduced by a pretty face. The irony is, of course, Shannon is no

more physically attracted to Charlotte, whom he rightly views as a child, than

he is tempted to betray her malicious custodian, increasingly hell-bent on

destroying his reputation with his most recent employer - Blake’s Tours. Periodically,

the eccentric Huston had known such malice and isolation in his own life, also,

physical frailty as a child due to ailments. He stubbornly dared – and mostly

succeeded – in triumphing over adversity, marrying too young and growing bored

with his early life decisions and career, running afoul of booze and broads

and, at a particularly low point, becoming a penniless beggar with little

interest in laying down more permanent roots. Huston’s enigmatic personality

and creative genius won him many friends amongst Hollywood’s hoi poloi – eager

to go slumming. But his reputation as a macho bad boy earned him just as many

detractors in the executive hierarchy of the studios.

We meet the Reverend Shannon after

MGM’s iconic Leo roars, a prologue where Shannon attempts to administer the

gospel to his flock, already diligently aware of his affair with a very young

Virginian Sunday school teacher. Now, they have mere come to gawk and admonish

him with their accusatory stares. Unable to continue, Shannon suffers a

horrendous breakdown, ostracizing his congregation and forcing them out of the

chapel into the pouring rain. We dissolve to a moody main title with various

close-ups of the famed lizard, set against Benjamin Frankel’s unsettling score.

Two years have passed during this brief interim. Shannon, now a frustrated

guide for Blake’s Tours, escorts a group of middle-aged Baptist school teachers

by bus around the various sites to be seen in Puerto Vallarta. Like Hitchcock,

both Tennessee Williams and Huston treat these matronly denizens with

broadsided mockery, presented as mindless, sexless and frumpy gargoyles,

fronted by the exceptionally brittle Judith, whose seventeen-year-old niece,

the sultry Charlotte, is her antithesis and an affront to all their suppressed

sexuality. Shannon is cordial toward Charlotte, perhaps, even unknowing at the

start, his kindnesses is considered a tease. But Charlotte has become smitten

with Shannon, whom she refers to with unsettling familiarity as ‘Larry’. Thus,

when Shannon attempts to escape the women in his tour group and disappear for

an impromptu swim while bus driver, Hank Prosner (Skip Ward) changes a flat on

the side of the road, Charlotte pursues Shannon into the ocean. Believing

Shannon is up to no good, Judith finds plenty to fault, threatening to expose

his prior peccadilloes to the rest of the travel group unless he refrains from

interacting with her ward for the duration of their trip. However, when Charlotte

sneaks off in the middle of the night and is later discovered in Shannon’s

hotel room, the resultant scandal is enough for Judith to make good on her

threats to have Shannon fired from his job.

Desperate to salvage even this

pathetic ounce of reputation, Shannon shanghaies the bus, driving it past the

prearranged next stop on their itinerary to prevent Judith from telephoning his

employer. Instead, he suggests a

refreshing change of pace at the remote Costa Verde hotel in Mismaloya,

overseen by his old pal, Fred and his wife, the uninhibited and bawdy, Maxine

Faulk (Ava Gardner in, arguably, the best role of her career). Removing the

distributor cap to prevent Hank from driving the ladies back into town, Shannon

encourages his hostages to take refuge inside the Costa Verde. Although

initially pleased to see Shannon, Maxine is decidedly unwelcoming toward this

congregation of women at first. After all, the hotel is closed for the season.

Her cook, Chang (C.G. Kim) is a marijuana addict, too perpetually stoned to prepare

anything for the guests. Shannon quickly discovers Fred, considerably older

than Maxine, has recently died of a heart attack, perhaps knowing all along of

his wife’s various paramours, including Shannon.

To his everlasting regret, Shannon

is also informed by Maxine, the Costa Verde now has telephone access. Judith

wastes no time putting in a call to Blake’s Tours and, after a thwarted first

attempt to get through, she is successful at exposing Shannon’s perceived

infidelities with Charlotte to his employer. Maxine is not fooled by Judith’s

ravenous desire to so completely enervate Shannon’s already dangerously low ebb

of self-preservation as a man. But Shannon has already figured out Judith’s

truer nature, her venom towards him both a shield and a mask to cloak her closeted

homosexuality. Preserving his last ounce of dignity, Shannon suggests, “Miss

Fellowes is a highly moral person. If she ever recognized the truth about

herself, it would destroy her.” Despite his genuine disinterest in

Charlotte, later to rupture her school girl’s crush in a hateful tirade and

other self-destructive ways, Shannon is promptly relieved of his command. While

Shannon sorts through this latest disgrace, still struggling to keep the

aggressive Charlotte at arm’s length and reconcile his truer feelings towards

Maxine, Hank, in a misguided notion of chivalry, engages in a fist fight with

Maxine’s cabana boys, Pepe (Fidelmar Durán) and Pedro (Roberto Leyva), whom

Charlotte has endeavored to seduce on the beach, and for whom Maxine has readily

exploited to satisfy her own frustrations even while Fred was still alive.

In the meantime, the hotel is

visited by Hannah Jelkes (Deborah Kerr), a wayfaring con from Nantucket,

peddling her amateur skills as a sketch artist in trade for room and board,

along with her decrepit grandfather, Nonno (Cyril Delevanti) whose claim to

fame is recitations of his poems. Reportedly, Nonno is working on his greatest

composition yet. Alas, the old man is

very close to death. Indeed, he will not outlive the next few days as Hannah

shores up and reconciles her sobering naiveté to reflect upon the crumbling

central relationship between Shannon and Maxine. Over the course of one stormy

night, Shannon suffers another breakdown, forcibly bound in a hammock by Pepe

and Pedro on Maxine’s say-so after he threatens suicide. Compelled to face his

demons – both flesh and the bottle, Shannon is revived. But Nonno dies after

completing his poem, an astute observation on man’s folly as he is driven to

confront the specter of death. If The Night of the Iguana does have a

moment of sobering epiphany, it is Nonno’s dying recitation, eloquently evolved

by Delevanti’s superb oration, his voice threateningly frail and parched,

quivering yet punctuating the appropriate syllables. “How calmly does the

orange branch observe without a cry, without a prayer, with no betrayal of

despair. Sometime while night obscures the tree, the Zenith of its life will be

gone past forever, and from thence, a second history will commence. A chronicle

no longer old. A bargaining with mist and mold. And finally the broken stem

plummeting to earth; and then, an intercourse not well designed, for beings of

a golden kind, whose native green must arch above the earth's obscene,

corrupting love. And still the ripe fruit and the branch observe the sky begin

to blanch, without a cry, without a prayer, with no betrayal of despair. Oh,

courage could you not as well select a second place to dwell? Not only in that

golden tree, but in the frightened heart of me?”

Hannah administers a home remedy of

poppy-seed tea to tranquilize Shannon’s anxiety. But only after the storm

clouds have broken, both literally and figuratively, is Shannon truly liberated

from this temporary psychosis and dominating despair. Suspecting Shannon may

have designs on Hannah, Maxine threatens a moonlit frolic with Pepe and Pedro

in the roaring surf, though painfully distracted by her own desire to possess

Shannon. By dawn’s early light, the

previous night’s indiscretions appear far less frightening to all. Shannon

realizes his place is with Maxine. After some initial friction, the two jointly

elect to run the Costa Verde and pick up where their previous affair left off

some time ago. Maxine, who initially

thought to ward Hannah off her property out of jealousy, now, instead, takes

pity on her. But Hannah has wisely decided the time has come to move on.

Without Nonno, she becomes the film’s singularly tragic figure, doomed to merely

drift along life’s road, a very inconsolable and unfamiliar path into an even

more unstable, and quite possibly, despairing future. The transference of Hannah’s

clear-eyed hope and promise into Shannon is, perhaps, a transgression, to

deprive her of any chance for the same.

The Night of the

Iguana is not as readily considered a part of John Huston’s top-tiered

entertainments. Perhaps, not – for it lacks something in Huston’s ability to

keep the story moving along, despite shifting locales and Gabriel Figueroa’s

luxuriating B&W cinematography. Infrequently, the platitudes espoused by

Richard Burton and Deborah Kerr linger just a tad too long as remnants of the

stagecraft, never lacking either in fire or music of their expert delivery, yet

queerly better suited for the stage than a movie. Interestingly, Huston and

producer, Ray Stark clashed on Huston’s decision to shoot the film in black and

white; Stark, hoping for a lush photographic travelogue to augment the drama,

while Huston firmly believed color would detract from the human story. Years

later, Huston conceded if he could do it all over again, he would have shot the

movie in color to underscore the yearnings and temptations depicted in the

story. Unquestionably, the various vignettes Huston has derived from Tennessee

Williams’ compelling stagecraft are all brilliantly realized in the film. The

acting from all concerned is of the absolute highest order. The heart of the

piece is divided between Cyril Delevanti’s subtly nuanced Nonno and Ava

Gardner’s far more lusty, whisky-voiced and unapologetically earthy Maxine. Only

in hindsight does Gardner’s performance cut too close to the bone of her own

personality. “I wish to live to be a

hundred and fifty,” Gardner (who died at the age of 68) once said, “…but

the day I die I wish it to be with a cigarette in one hand and a glass of

whiskey in the other.” Indeed,

Gardner’s reputation as a Hollywood bad girl was legendary, bringing these

well-traveled exploits to her characterization of a very gutsy gal, teetering

on the verge of an almost irredeemably volatile disposition.

Unwilling to allow Judith Fellowes

her victories over Shannon, Gardner brings an unprecedented conviction to her

double entendre inquiry, “What subject do you teach back in that college of

yours, honey?” When Judith curtly admits “Voice... if that's got

anything to do with it”, Gardner’s Maxine follows up with the even more

loaded, “Well geography is my specialty. Did you know that if it wasn't for

the dikes the plains of Texas would be engulfed by the gulf?” Gardner,

married and divorced three times already by the time she made The Night of

the Iguana, wields voracious, if careworn clear-eyed exuberance when she says

the line, “Even I know the difference between lovin' somebody, and just

goin' to bed with them. Even I know that”; her unvarnished sadness wed to

an even more sustaining avuncular threshold for all wounded creatures. “The

truth…”, Gardner would later commit to paper in her scalding memoir, “…is

that the only time I'm happy is when I'm doing absolutely nothing. I don't

understand people who like to work and talk about it like it was some sort of

goddamn duty. Doing nothing feel like floating on warm water to me. Delightful,

perfect.”

Indeed, Gardner shared something of

Huston’s scorn for the power structure that had made them both famous.

“Being a film star is still a big damn bore,” she repeatedly pointed out, “Apparently,

I'm what’s known as a 'glamour girl.' Now that's a phrase which means luxury, leisure,

excitement, and all things lush. No one associates a six A.M. alarm, a

thirteen-hour workday, several more hours of study, housework, and business

appointments with glamor. That, however, is what glamor means in Hollywood. But

being a movie star in America is the loneliest life in the world. In Europe

they respect your privacy. At least I'm one Hollywood star who hasn't tried to

slash her wrists, take sleeping pills, or kick a cop in the shins. That's

something of an accomplishment these days. But take my advice, honey. Hollywood

is just a dreary, quiet suburb of Los Angeles, with droopy palm trees,

washed-out buildings, cheap dime stores, and garish theaters; a far cry from

the razzle-dazzle of New York, or even the rural beauty of North Carolina.”

One senses Gardner’s distaste for

the superficialities of the system that made her legend, rechanneled into her

characterization of Maxine Faulk, something about the way she lends the

impression not to give a hoot about how she looks – a trumped up glamor girl

eagerly gone to seed, with disheveled hair, her baggy, wrinkled shirt

perpetually untucked, generally lacking the anticipated poise of such

romanticized statuesque celluloid beauties as she slithers, saunters and

playfully trips about the landscape with an infectiously erotic liquidity and

fairly to smell of sex as she playfully threatens to knock Judith Fellowes

teeth out, or taking rich pleasure in Shannon’s debacle to rid himself of the

overenthusiastic Charlotte. “It's

very serious,” Shannon tries to explain, “The child is emotionally

precocious.” “Well, bully for her!” Maxine declares.

The Night of the

Iguana would go on to earn 4 Oscar-nominations, its singular statuette to

Dorothy Jeakins for costume design. Respectable, if not mind-boggling, box

office aside, the movie has steadily earned its rightful reputation as a great

movie, despite Tennessee Williams’ reflections made to Huston some six years

later, “I still don’t like the finish, John.” Nevertheless, the making

of the movie would leave an indelible impression on Huston who, after years of

renting a home in Puerto Vallarta, became a respected member of the Chacala

Indian community, south of Boca de Tomatlan, leasing the land for ten years,

with an additional ten year option, after which time it was returned to the

Chacalas. For a time, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton would also reside in

the vicinity, in a decidedly plush nine-bedroom villa dubbed Gringo Gulch,

contented to be left alone by the locals who respectfully afforded them some

semblance of a ‘normal life’. Of all

their various residences around the world, Taylor would often profess to Mexico

where she felt the most at home. After their marriage ended, Burton would

return to Mexico with his new wife, Susan Hunt, who maintained lasting

friendships in Puerto Vallarta long after Burton’s death. To mark the 25th

anniversary of the making of the movie, a bronze statue of Huston was erected

on the River Cuale in 1989.

The Night of the

Iguana looks utterly resplendent, arriving on Blu-ray from the Warner Archive

WAC) Prepare to bask in the sumptuousness of Gabriel Figueroa’s stunningly

handsome B&W cinematography. Age-related

artifacts have been eradicated. Contrast is uniformly excellent and fine detail

could not be more completely realized. This is a reference quality affair from

WAC. Given that it is WAC, we should expect no less. The DTS 2.0 mono places

clean/clear dialogue slightly ahead of Benjamin Frankel’s music score with SFX

sounding properly placed as well. WAC has ported over the brief featurette The

Night of the Iguana: Huston’s Gamble with very brief reflections from film

historians, Donald Spoto, Lawrence Grobel, and Eric Lax. We also get the vintage

featurette, On the Trail of the Iguana made by MGM to promote the picture’s

theatrical release, plus two trailers. In

a perfect world, I would have hoped for an audio commentary to accompany this

fine film. Oh, well – can’t have everything. Bottom line: The Night of the

Iguana remains one of John Huston’s finest films, and one of the greatest

of all achievements to come out of Hollywood – period. WAC’s new-to-Blu gives us

the perfect way to experience this powerhouse entertainment. Buy today, treasure

forever. Very – VERY – highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out

of 5 – 5 being the best)

4.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

5+

EXTRAS

1

Comments