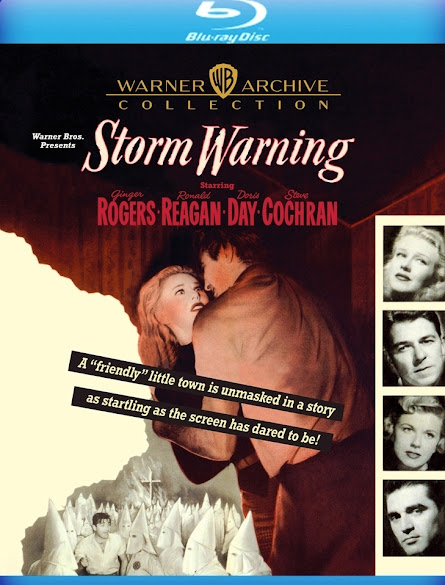

STORM WARNING: Blu-ray (Warner Bros., 1951) Warner Archive

Doris Day proved she was more than

just a healthy set of lungs with the singing pipes to match in director, Stuart

Heisler’s Storm Warning (1951), a movie to continue Warner Bros.’

commitment to the sort of hard-hitting melodramas once exclusively to have

found their home at the studio. Precisely how Day came to appear in this

powerful indictment on small-town bigotry has become a little muddled with

time. Various sources suggest Day was always in the running to play Lucy Rice,

the naïve, younger sister, wed to Hank (the tragically underrated, Steve

Cochran) a vial racist whose bravado masks a lily white streak of abject cowardice. But the part of Lucy’s elder sis’ – Marsha Mitchell

(eventually played by Ginger Rogers… another legendary musical talent seeking

to divest herself of that peaches n’ cream image) was initially offered to Joan

Crawford, then cresting to a full stop on the Warner gravy train, initially

kicked into high gear a scant 6 years earlier with her Oscar-winning

performance in Mildred Pierce (1945). Crawford reportedly balked at

playing Day’s elder sibling, as Day’s ‘squeaky clean’ persona, dubbed by the

great Groucho Marx as ‘America’s oldest virgin’, decidedly clashed with Crawford’s

rough and slightly déclassé dames. It is, however, and perhaps, a bit of a stretch

to consider Day as the frontrunner for Storm Warning as there was

nothing in her Hollywood debut in 1948’s Romance on the High Seas, or

the five, frothy studio-bound musicals to follow it to infer Day’s marketable

skills could – or should – be expanded upon beyond her golden-haired/wholesome

Suzie Cream-Cheese façade. Mercifully, Day proved more than just another pretty

blonde in Hollywood’s Tiffany-setting.

Storm Warning is credited

with earning Day enough cache as a dramatic actress to impress Alfred Hitchcock,

shortly thereafter to cast her in his 1956 remake of The Man Who Knew Too

Much. Alas, the role of Marsha proved a tougher nut to crack. After

Crawford’s flat out rejection, Jack L. Warner pegged Lauren Bacall for the part.

But Bacall had since become mistrusting of the studio that had effectively launched

her as a bona-fide box office bombshell in To Have and Have Not (1944),

only to as easily derail her burgeoning prospects with a pair of screen duds,

and then, a questionable, and even more uneven spate of projects that left

Bacall wanting for meatier roles. Bacall, instead, trusted her future career to

husband, Humphrey Bogart who – then, off on the ordeal of shooting John Huston’s

The African Queen (1951) had little time to advise his wife on how best

to proceed. Perfectly contented to pass on Storm Warning, Bacall

followed Bogart on his great adventure – in the process, having one of her own,

only to discover that, in her absence Jack Warner had elevated her suspension

to an outright cancelation of her contract. So, again in hindsight, the casting

of Ginger Rogers to play Day’s sage sis’ proved fortuitous. Prior to becoming a

big band vocalist, Day had aspired to be a dancer. Rogers was her childhood

role model. When Rogers discovered this, she embraced Day and the two got on

famously.

Storm Warning is also notable

for the final appearance of Ronald Reagan in a Warner Bros. picture. Reagan’s 7-year

contract had yielded some intermittent promise in high-profile pics like Knute

Rockne: All American (1940), Kings Row (1942), This Is The Army

(1943) and The Hasty Heart (1949), only to have his technical

proficiency overrun in a series of highly disposable and artistically questionable

fluff and nonsense that, while keeping Reagan employed, did little to advance

his reputation as a serious actor. Storm Warning may not be Reagan’s

finest hour on the screen, but it irrefutably illustrates what a finely honed presence

he had become during his indentured servitude at the studio. Playing the

repugnant villain to Reagan’s saintly lawman, Burt Rainey, Steve Cochran added

yet another heavy-handed thug to his repertoire of distorted brutes. Like Reagan,

Cochran aspired to more than just typecasting as the studio’s hairy-chested

tough guys. Unlike Reagan’s aspirations to be more/do more outside of making

movies, Cochran had dreams to launch an indie production company of his own.

This would remain unfulfilled as, while on a location scouting trip in

Guatemala in 1965, he suddenly succumbed to a rare lung ailment and died aboard

his yacht before ever reaching dry land.

Herein, it behooves us to take

notice of Cochran’s swarthy sex appeal. Even when playing a coldhearted

bastard, Cochran possesses a strangely compelling animal magnetism. In Storm

Warning he is a transparently wan, roadshow Stanley Kowalski to Day’s

Stella-esque reincarnation with Rogers bringing up the Blanche Dubois angle

from behind (Warner Bros. debuting its film version of A Streetcar Named Desire

this same year). If the studio helped to shape Cochran’s screen aura into that

of an olive-skinned bad boy, they certainly had plenty of real-life material to

draw from; Cochran, a tabloid-fav for his boozin’/brawlin’ and his tom-catting,

first flexed while still a student at the University of Wyoming. Rather impulsively,

Cochran traded in his collegiate days for stardom, first to be taken seriously

as a theater actor in Carmel. Cochran’s film entry, playing – what else?

– the heavy, opposite a brilliant Danny Kaye in Wonder Man (1945) paved

the way for a decade’s worth of juicy parts at his alma mater. Indeed, just

prior to Storm Warning, Cochran could be seen ruthlessly inveigled with

Joan Crawford’s crooked socialite, Lorna Hanson Forbes in the great noir

thriller, The Damned Don’t Cry (1950).

Storm Warning opens with the

arrival of fashion model, Marsha Mitchell at the train depot in the seedy

backwater of Rock Point. Marsha hopes to briefly visit her newlywed sister,

Lucy Rice. Alas, just moments from the depot’s steps, Marsha witnesses the main

street of this town suddenly go dark and members of the KKK lynch a man newly

sprung from the county lockup. She also gets a pretty good look at two of the Klansmen

before hurrying to the nearby bowling alley where she discovers Lucy. After

regaling Lucy with the facts of the crime, Lucy confides in Marsha the deceased

must be Walter Adams, an undercover journalist investigating the Klan. As

members of the local police also belong to the Klan, Adams was promptly arrested on a false charge of

driving while intoxicated. Armed with this information, Lucy encourages Marsha

to follow her home and tell her husband, Hank about the incident. But when

Marsha arrives, she suddenly realizes Hank is one of the Klansmen she witnessed

standing over Adams’ body in the street.

Marsha confides this to Lucy. Hank,

eavesdropping on their conversation, at first threatens Marsha to remain

silent, then, feigns a breakdown, suggesting he was complicit in the murder

merely to save face with the rest of the townsfolk. According to Hank, the Klan

just wanted to scare Adams out of town. Things got out of hand and Adams wound

up dead. Marsha is not buying any of this but remains silent for the moment,

owing to Lucy’s blind forgiveness of her man whose child she is currently

carrying. Marsha vows to leave town. But then, D.A. Burt Rainey arrives,

pressing the local police in their investigation of the murder, and also, doing

his own legwork to get to the bottom of things. This eventually leads Rainey to

grill Charlie Barr (Hugh Sanders), the KKK’s Imperial Wizard, alas, to no

avail. Learning the crime might have a witness he can use, Rainey involves

Marsha in his search for the truth. Regrettably, mislaid loyalties endure.

Marsha lies under oath during the inquest, claiming that while she witnessed

the murder, she cannot identify any of the men involved as they were all hooded

at the time.

Disgusted by her spinelessness,

Marsha hurries to pack and leave town. Instead, she is confronted by a drunken

Hank who tries to rape her. Mercifully, Lucy’s arrival thwarts the inevitable.

The girls vow to leave town together. Instead, Hank kidnaps Marsha and carts

her off to the KKK rally where she will be made to atone. Marsha is flogged at the rally until Lucy

arrives with Rainey and the police in tow. Barr momentarily conceals Marsha.

But her whimpers are overheard by Rainey who, discovering her badly beaten, demands

answers. Barr points an accusatory finger at Hank, fingering him for Adams’ murder

too. A panic-stricken Hank shoots Lucy before being gunned down by the police.

The rest of the Klansmen flee in fear, leaving only a half-burnt cross behind. Barr is taken into custody for his complicity

as Lucy quietly expires in Marsha's arms, leaving Rainey to comfort her.

More than any other picture made at

Warner Bros., and certainly more than any, as yet, produced under the imprimatur

of Jerry Wald, Storm Warning represents one of the shadiest chapters in

American history as humanity’s weak acquiescence towards an evil it deems as ‘necessary’

to maintain its even more fragile and darkly purposed status quo. Daniel Fuchs and Richard Brooks’ screenplay does

not go all the way in extolling the racial component of the Klan. Rather, the

picture focuses on the Klan’s infiltration as a rogue element in an otherwise ‘civilized’

small town complicit in its proliferation, counterbalancing this disturbingly

monolithic - nee fascistic embrace as its’ ‘under the radar’ law and order with

the moral forthrightness of a handful of ‘good’ people, unafraid to withstand its’

nihilism. That the finale does not bear out Hollywood’s time-honored cliché of

good triumphing over evil, even to infer valor and virtue as possessing no

rewards, but to make a sacrifice of the noblest of the lot – Lucy Rice – only

amplifies the fragility of American democracy, in constant flux for

affirmation, protection and validation. Though deemed by the studio an ‘important’

picture, Storm Warning never lived up to its reputation with audiences

or the critics.

Storm Warning’s arrival on

Blu-ray via the Warner Archive (WAC) is predictably another quality affair,

delivering a startlingly precise image with razor-sharp clarity to extol all of

the virtues in Carl Guthrie’s deep focus B&W cinematography. It all looks

as it ought, with a sumptuous amount of fine grain coming to the forefront and

fine detail popping – especially in close-up. Age-related artifacts are gone.

The DTS 2.0 mono sounds crisp, with Daniele Amfitheatrof’s ‘on the nose’

score achieving the proper register in orchestral bombast. Apart from a badly

worn theatrical trailer, and a pair of short subjects, there are no extras. Not

much else to say here – another solid effort from WAC of an important picture

that never entirely achieved the sort of notoriety it deserved upon its

theatrical release and, in the interim, has all but unfairly vanished from

popular view. Very highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out

of 5 – 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

4.5

EXTRAS

1

Comments