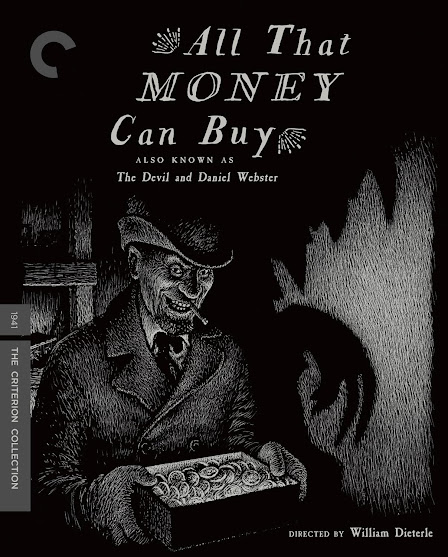

ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY: Blu-ray (RKO/William Dieterle Productions, 1941) Criterion Collection

Odd,

perhaps, to classify director, William Dieterle’s 1941 masterpiece, All That

Money Can Buy (a.k.a. The Devil and Daniel Webster) as a

fantasy/horror movie. For the struggle at the root of all evil – man’s love of

the all-mighty buck – is the very crux of this darkly purposed and sinister

drama, given to exquisite performances by James Craig and Anne Shirley, as the

titular God-fearing, backwoods couple, Jabez and Mary Stone. The tale is that

of a man, Jabez, so miserably under siege by hardship and ever-teetering financial

ruin that, in a moment’s weakness, he offers to sell his soul to the devil for

two cents; a bargain he will fast live to regret. For the devil’s emissary on

earth, Mr. Scratch (Walter Huston in a deliciously grotesque, and, deservedly

Oscar-nominated turn), is more than willing to oblige Jabez…for a price.

Ever-lasting damnation in trade for seven years earthly prosperity may seem

like an implausible cost to bear. Yet, daily who among us has not fleetingly reconsidered

giving up this intangible to a more tactile manifestation weighed against the

hard-won sweat off our brows?

All That Money

Can Buy is a cautionary tale, most directly aimed at the Bible-belted, rural

enclaves of humanity, otherwise left mostly to their scripture and faith to

etch out renewed meaning from their lives of quiet desperation. And, rather

unknowingly, the picture since serves as an ominous precursor for the way of

the world as it stands. What the devil could make of our present-age’s fame-mongering/money-hungry

hedonism, bent on mass consumption to medicate our unbearable lightness of

being at a loss of friendship, family, the love of a good man or woman, and

children…ever-more needed to reshape our definition of prosperity for the

future. Immediately following the

success of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939), director, William

Dieterle founded his own production company, inking a distribution deal with RKO

Radio Pictures. Dieterle’s interest in Stephen Vincent Benét's short story

likely hailed from his participation on director, F. W. Murnau's silent adaptation

of Faust (1926). Undeniably, similarities abound between these two

movies. Benét was, in fact, encouraged to adapt his story for the screen, working

with Dan Totheroh. The results proved fruitful, with Benet agreeing to some

changes along the way. In the short story, Daniel Webster (played with slick

incredulity by Edward Arnold, in a role originally intended for Thomas Mitchell)

regrets Benedict Arnold's absence from Jabez Stone’s trial. In the movie, Webster

objects to Arnold’s presence, citing his treason. Perhaps most astonishing of

all, Mr. Scratch evolves into a far more subtly nuanced menace, deferring the

more ambitious seduction to the wiles of Belle (Simone Simon), a flashy viper,

expressly created for the movie with no counterpoint in Benet’s original story.

All That Money

Can Buy is an exquisitely tailored production. Interestingly, RKO refused to

allow Dieterle to release the picture under Benet’s short story title, as it

clashed with their own newly released The Devil and Miss Jones (1941).

In later years, the original titles were discovered, as well as an alternate – Here

Is A Man. Intermittently thereafter, All That Money Can Buy would be

reissued theatrically under all three. Though All That Money Can Buy was

shot on a relatively modest budget, Dieterle placed his emphasis on where it would

do the most inherent good; first, on his expert pacing and personally-selected

cast, also to include beautifully understated performances by Jane Darwell (Ma

Stone), H.B. Warner (Justice Hawthorne) and, John Qualen (Miser Stevens). The moody magnificence in Joseph H. August’s

B&W cinematography should not be overlooked either. August creates

foreboding almost from our first introduction to the Stone family. His debut of

Mr. Scratch, materializing through translucently apocalyptic mist beyond the

barn, is truly mesmerizing. Finally, Bernard Herrmann’s Oscar-winning score – a

deft combination of original cues and source music derived from folk tunes

(culminating in a demonic elucidation of ‘Pop Goes the Weasel’ – staged

as a country dance by Dieterle and shot by August in deliriously stark half

shadows) is an overpowering experience.

The year is 1840.

The place: New Hampshire. We are introduced to the agrarian, Jabez Stone, proud,

but drowning in debt and personal mishaps. Nothing seems to go Stone’s way. After

his wife, Mary takes a tumble from their carriage, a thoroughly frustrated

Stone impetuously asserts he would trade his soul for two cents. Enter, Mr.

Scratch with an offer much sweeter than this: seven years of good fortune and

prosperity. Scratch produces a hoard of Hessian gold bubbling up from the straw

in Jabez’s barn, an enticement for him to sign the contract. Flush with money,

Jabez pays off his creditors and embarks upon his new life with great hope and

desire to make a success of things. Driving Mary and Ma into town, Jabez is

introduced to the celebrated congressman/barrister/orator, Daniel Webster, the

working man’s friend. Scratch has failed to tempt Webster into selling his soul

for the U.S. Presidency. So, Scratch invests everything in transforming Jabez

from poor country courtier into a dandy, alienated from Mary and Ma. After the

birth of their son, Scratch replaces the family’s maid with Belle, whose

dishonorable seductions becomes more disingenuously disturbing and obscene with

the passage of time.

Belle bewitches

Jabez. But she also corrupts his son, Daniel (Lindy Wade) who matures into a

petulant brat. Indifferent to Mary’s heed and advice, Jabez pursues his

pleasures with Belle, building an ostentatious manor where he intends to show

off to all their friends. Alas, the party turns nightmarish when Miser Stevens,

partly responsible for forcing Jabez to consider Scratch’s initial offer, now

confides to Jabez he too has sold his soul to the devil. Belle lures Stevens to

the dance floor where he succumbs to a heart attack. Evidently, his contract with

Scratch is up. Fearful of suffering the same fate, Jabez tries to destroy the tree

on his property where Scratch had earlier burned the expiration date for their

contract into its bark. Alas, nothing will undo this curse. Horrified, Jabez

pursues Mary and Webster, pleading for their forgiveness and help. As Webster’s

reputation as the foremost defender of the moral good precedes him, he takes

the case. Scratch now appeals to Jabez on an extension of their terms in

exchange for young Daniel’s soul. Jabez is repulsed. Now, Webster leverages his

soul against a chance to defend Jabez in a formal trial. Scratch is intrigued,

but stacks the jury pool in his favor from a rogues’ gallery of past victims/villains.

Scratch also places Salem ‘witch hunt’ justice, John Hathorne on the magistrate’s

bench. However, Webster’s defense is as eloquent as it is simple. While all are

entitled to ‘choose’ their destiny, the fates of the jury have already been

decided. By contrast, Jabez’s soul is up for grabs. It can be saved.

Hathorne concurs. Jabez’s contract with Scratch is declared null and void. In

reply, Scratch bitterly recedes, though not before promising Webster he will

never be president.

All That Money

Can Buy is a sobering indictment of man’s enduring inability to reign in his

greed. Jabez Stone’s case is neither extraordinary nor unique. Indeed, he

represents the fate, as well as the folly of the ‘God-fearing’ though hardly

infallible ‘everyman.’ While the focus of the tale is Jabez’s plight, the

original short story’s title implies a more concerted focus on the righteous Daniel

Webster pitted against the moral depravity of Satan. The movie, however, is directly

invested in the Stone family. This, suspiciously renders its narrative

uncomfortably situated for the penultimate showdown between good and evil, as

Jabez Stone is not entirely without malice or flaws, and, Mr. Scratch bears

more than a modicum of devilish good nature, rendered playful, and even

marginally appealing. Walter Huston’s performance as the emissary of evil is

without peer. Calculatingly lit and photographed by Joe August with a

pervasively pale glint of larceny perpetually caught in his eyes, Huston’s insidiously

gentle demon is, at once, powerfully appealing, yet socially disturbing as a

figure of mendacity. Initially released at 107-mins., All That Money Can Buy

was a critical, though not a commercial success, incurring a loss of $5300 on

RKO’s ledgers. Its title was later changed to The Devil and Daniel Webster

for reissues. But by then, RKO had pared its runtime to a scant 85-mins. without

Dieterle’s consent – rendering its narrative almost incoherent. Mercifully, the

cuts survived and were later reinstated in a 1990 reissue.

All That Money

Can Buy arrives on Blu-ray via Criterion in a refurbished master, gleaned from

surviving nitrate camera negatives and meticulously restored in cooperation

with the film and television archives of UCLA, MoMA, and the Library of

Congress. The results yield an

impressive image unseen for decades. Gray scale tonality is superbly rendered.

Fine details abound. Contrast is uniformly excellent. The image is crisp

without any untoward digital tinkering. Grain structure remains intact. The PCM

mono audio is impressive. Top marks for quality. Not

so much for the ‘goodies’ Criterion deigned to include herein. Virtually nothing is

new. The commentary from historian,

Bruce Eder and Steven C. Smith, as well as Smith’s video essay are from the 2003

Criterion DVD release. We also get Alec Baldwin reading Benet’s short story –

again, from 2003. Finally, there are radio adaptations of two of Benet’s short

stories and a theatrical trailer. Author, Tom Piazza leads with a brief essay

in print. Bottom line: a movie of grave social significance, unseen for

decades, but now presented for future generations to study, admire and

critique. Bottom line: highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out

of 5 – 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

4.5

EXTRAS

2

Comments