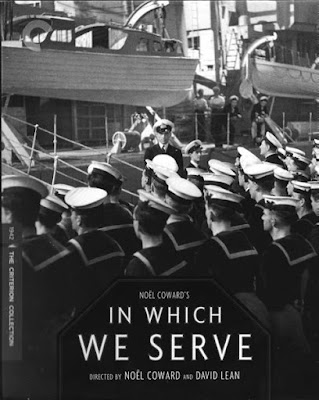

IN WHICH WE SERVE: Blu-ray (British Lion 1942) Criterion Home Video

Few wartime

movies are as unabashedly patriotic, or as sentimentally moving as Noel

Coward's In Which We Serve (1942); a

glowing testament to those gallant fighters in Britain's merchant marine. Yet,

the story is not at all about these brave men per say, but rather, the tale of

a ship - the H.M.S. Torrin - and her faithful crew. Co-directed by David Lean

and Coward (who also wrote the screenplay and the score, produced, and, starred

in the film), In Which We Serve is

an extraordinarily understated cinema classic. It is the film that brought Noel

Coward out of his self-imposed exile from the motion picture business (that the

playwright always regarded as an inferior medium to live theater), and cemented

an enduring friendship with his collaborators Lean, screenwriters Ronald Neame

and Anthony Haverlock-Allen.

Reportedly,

Noel Coward was enticed into making the film after he approached Prime Minister

Winston Churchill (a close personal friend), offering to do his part in the war

effort. Coward had eluded active duty in the First World War due to

tuberculosis, and this had left him feeling rather disloyal to England.

Churchill, however, was not moved by Coward's impassioned plea to partake in

WWII as an enlisted man. In the meantime, Capt. Lord Louis Mountbatten (another

personal friend of Coward's) had just returned on leave from duty after his

ship, the H.M.S. Kelly had been sunk by Nazi torpedoes during the battle of

Crete. Regaling Coward with this fateful tale gave the playwright his

inspiration, as well as the impetus to write In Which We Serve (the only work Coward expressly wrote for the

screen).

But it was a

screenplay for a six and a half hour movie. Owing to Coward's immense stature

and formidable reputation in the entertainment world, Haverstock-Allen tread

lightly when suggesting that his masterwork would have to be re-written (or, at

the very least, pruned down to a manageable size). Apart from being a genius

and a wit, Coward was also one of the most congenial and compassionate writers of

his generation. He wholeheartedly agreed, allowing Haverstock-Allen and Neame

to edit his prose.

David Lean's

contributions on the film were an entirely different matter. Although Lean was

only a 'cutter' (the term for a film editor in those days) before filming

began, Coward had admired his clever and intuitive pacing. He also knew that

Lean desperately wanted to direct. But Lean was shrewder about his future than

that. Asked by Coward to 'assist' on the film, Lean politely inquired first

about the credits, agreeing to do the film only if his title card read

'Directed by Noel Coward and David Lean'. Coward, happily agreed and thereafter

afforded Lean every professional courtesy on the set, choosing to 'work' with

the actors on their performances while Lean concerned himself with the actual

staging and execution of the scenes; a mutually rewarding and beneficial

alliance that would ultimately yield three more screen collaborations.

The film opens

with an odd declaration by Leslie Howard; "This

is the story of a ship!" and for the next several minutes we are,

indeed, privy to an extensive montage of clips depicting the construction,

launch and battle man oeuvres of the H.M.S. Torrin; a destroyer stationed off

the coast of Crete in 1941 and captained by E.V. Kinross (Noel Coward). The men

under his command are embroiled in a merciless sea battle that ends tragically

when the Torrin is mortally wounded in an aerial attack by a fleet of German

bombers.

Forced to

abandon ship, some of the officers and crew take refuge on a Carley float where

they endure constant strafing from overhead. The rest of the story is told in

flashback - at first clumsily so - as each survivor reflects on both his home

life back in England, and his home away from home - the Torrin - now resting at

the bottom of the sea. We see the Captain comfortably in his middle class

cottage before the war, with dotting wife, Alix (Celia Johnson) and his two

children nestled at his side. We meet Chief Petty Officer Walter Hardy (Bernard

Miles) and his wife, Kath (Joyce Carey) and her mother-in-law Mrs. Lemmon (Dora

Gregory) who lives in a London flat under constant fear of the blitz. And we

are introduced to ordinary seaman, Shorty Blake (John Mills) who falls in love,

and is eventually married to Freda Lewis (Kay Walsh). Freda is related to

Hardy. After she becomes pregnant she moves in Kath and Mrs. Lemmon while the

men are away at sea.

The Torrin is

engaged in a naval battle off the coast of Norway and narrowly escapes sinking.

During this skirmish a young powder handler (Richard Attenborough) cracks under

the pressure and abandons his post. While Capt. Kinross is a stern commander,

he also believes that a happy ship makes for a constructive crew. He lets the

handler off with a warning, accepting part of his shame as his own for not

having more time to properly train him before sailing into battle. As fate

would have it, not all the casualties of war are to be found on the front

lines. As Freda nears the due date of her pregnancy, a bomb strikes the Hardy

home, killing Kath and Mrs. Lemmon. After Freda gives birth in an Army Hospital

she writes Shorty of the news and he stoically relays it to a disbelieving

Hardy, who suddenly realizes he has lost everything he holds dear.

We return to

the survivors of the Torrin still clinging to their raft. These few men are

rescued by another ship and Capt. Kinross comforts the wounded and dying below

decks. He also learns that more than half of the Torrin's crew was lost at sea.

Telegrams are sent home, and both Alix and Freda learn that their husbands are

safe. Kinross and the survivors are taken to Alexandria Egypt to regroup and

recuperate. After being informed that his crew is to be broken up and sent to

other ships to continue their valiant fight, Kinross offers a rousing speech to

his men that is as inspirational as it is heartrending. An epilogue declares

that bigger ships will come to avenge the fate of the H.M.S. Torrin.

In Which We Serve is undeniably rousing

entertainment. Yet, its opening act rather inelegantly sets up each flashback

with overwrought melodrama and somewhat disjointed vignettes. The first thirty

minutes of the film seem quite uninspired - bordering on dull - with Coward

somewhat out of place wearing Mountbatten's actual naval cap as he commands the

crew of the Torrin. Coward, it should be noted, did not come from a cultured

upper class background. But throughout the 1920s he had cultivated an adroit

wit and effete charm that seemed to belie his lower middle class upbringing.

This became problematic when Coward cast himself as the star of In Which We Serve - and, in truth,

during these opening scenes he remains a little hard to swallow as the modest

everyman.

But about

midway through the story, Coward sheds this carefully crafted public persona.

He reveals to us an uncharacteristic humbleness and great humanity that is most

sincere and quite devoid of his usual droll mannerisms, so much that when - as

the Captain - he arrives at the last act of the film, proudly embracing the

camaraderie of his surviving crew, we believe Coward in his every nuance and

syllable. The fate of these heroic men has become quite personal, not only to

the Captain, but also to Coward and his performance makes their plight (as well

as that of the real fighting men) even more intimate and enduring for the

audience.

In Which We Serve was hailed as a masterpiece upon

its premiere and earned Noel Coward a special Oscar. Today, it remains an

engrossing WWII 'propaganda' film with few equals. The collaboration between

David Lean and Coward gave Lean his true start in films and yielded three more

emblematic of the best in British cinema. It also allowed Coward to re-assess

his initial opinion of the movies as an inferior entertainment. Although Coward

would always regard live theater as his first love, the movies he made with

Lean elevated the stature of that medium for him. Despite changing times and

cinematic tastes, the emotional center of In Which We Serve remains as poignant

and relevant as ever. This is a great film.

Criterion's

Blu-ray, in conjunction with a meticulous 2008 restoration effort by the BFI,

has resulted in a beautiful 1080p transfer with a few minor anomalies. The gray

scale has been impeccably rendered. The finely detailed image is solid with a

modicum of naturally occurring film grain. Even matte shots and rear projection

look natural. What is regrettable is the hint of edge enhancement that

continues to occur - however briefly - during a few key sequences. Because the

rest of the film is razor sharp and solid, this intermittent anomaly is all the

more apparent when it occurs. The audio is mono but has been very nicely

restored for a smooth sonic representation that will surely not disappoint.

Extras include

Barry Day's reflections on the making of the film, a profile featurette that

covers a lot of the same ground with snippets from the film and interviews with

Haverstock-Allen and John Mills, and an extensive 'audio only' 1969 Q&A

that Richard Attenborough hosts with Noel Coward in front of a live audience.

At present In Which We Serve is only

available as part of Criterion's David

Lean Directs Noel Coward box set that also includes Blithe Spirit, This Happy Breed and Brief Encounter. Highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out of 5 - 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

3

Comments