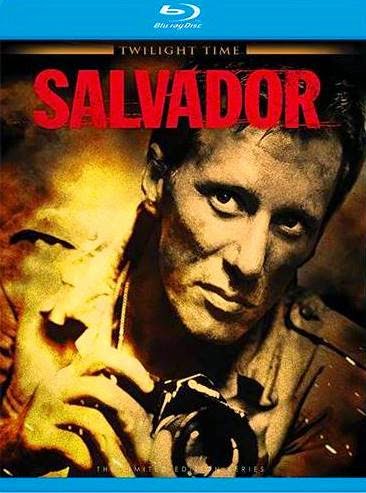

SALVADOR: Blu-ray (Hemdale 1986) Twilight Time

Oliver Stone’s

movie career has been the stuff of controversy. Perhaps, Stone wouldn’t have it

any other way. Whether critiquing the emasculating neuroses of shell-shocked

veterans, or tackling volatile conspiracy theories surrounding the assassination

of the president, Stone’s ‘nothing

ventured/nothing gained’ attitude, coupled with a telescopically focused

belief in his own opinions, and, his keen film maker’s eye laying bare the

hypocrisies of our time, has yielded a veritable treasure trove of cinéma vérité. A self-professed ‘wild man’, Stone has been

oft’ misjudged - and harshly – for his maverick ways. Critics have ranged in

their appraisal of his film making prowess from exaltation to indifference to

open hostility. Audiences, however, regard him as one of the leading

clairvoyants in our postmodern age; bucking trends, probing history and putting

forth alternative perspectives that engage, as well as enlighten. There is an

edginess to Stone’s art. Passionate, clear-eyed and possessing an innate

mistrust – nee contempt for authority – especially, toward injustices

perpetuated for political gain – Oliver Stone has, at times, been the lone

voice for the social, moral and constitutional redemption of the United

States.

Salvador (1986) remains Oliver Stone’s mislaid gem; channeling

the director’s penchant for politically charged in-your-face drama set against

a broader canvas of civil unrest. In some ways, Stone’s métier is not unlike

that of the immortal David Lean; albeit, with a darker, grittier edge. All but

ignored upon its release, snubbed at the Oscars (3 nominations but no wins) and

virtually eclipsed in the public’s estimation by Stone’s other monumental

contribution of the year – Platoon

(1986), Salvador’s reputation, like

its’ director’s, has only ripened with age. The film is, in fact, a powerful

indictment on the crisis in El Salvador and America’s financial involvement

that helped to perpetuate a despicable high command, responsible for the murder

of nearly 75,000 civilians. The Stone/Boyle

screenplay begs a burning question: how can a country survive when the

proponents for legitimate peace are allowed to be dismantled in favor of a

puppet regime funded by America?

Salvador had an inauspicious beginning; Stone casually bumping

into renegade photojournalist, Richard Boyle and discovering an oil-stained

manuscript kicking about the backseat of his rather filthy car. Inquiring as to

its contents, Stone was informed by Boyle he had written down stories of his

time in El Salvador; his recollections of the people and bloody civil war

sparking Stone’s imagination. Boyle assured Stone no one was interested in the

manuscript. After all, he had shopped it around to various publishers but to no

avail. Stone, arguably, a sucker for the underdog was immediately intrigued. By

1985, Boyle was regarded as something of a ‘has been’; his methods for covering

a story too ‘out there’ for any legitimate media service to put him on their

payroll. What Boyle had, in fact, written was the brutal rape and murder of

humanitarian worker Jean Donovan and three nuns; names changed in the movie to

Cathy Moore (Cindy Gibbs) and Sisters Stan (Dana Hansen), Burkit (Sigridur

Gudmunds) and Wagner (Erica Carlson) at the hands of the Juntas; also, about

America’s involvement in propping up of a known corrupt administration with

financial support, for no other reason than because they were not communists;

thus, considered the ‘lesser’ of two evils.

Moving Richard

Boyle into his guest house, Oliver Stone hammered out a manageable screenplay

in three weeks, shopping the property around with little success. Undaunted,

Stone prepared to throw in his own capital behind the project; Hemdale

Entertainment signing on to produce and distribute the film. For authenticity,

Stone pursued Robert E. White, the former U.S. Ambassador to El Salvador from

1979-81; the years Salvador – the

movie – takes place. However, perusing an early draft of the screenplay, White

was appalled by its blend of crude comedy and ultra-violence which he found

irrelevant and strangely perverse. Opting out necessitate a name change; Stone

further muddying the waters by making his rechristened Ambassador Thomas Kelly

(Michael Murphy) the ineffectual fop of the piece.

Stone’s

initial plan had been to shoot Salvador with

Richard Boyle playing himself; the entire production set in its authentic

locale, with Stone bribing the regime with a phony screenplay in which the

Juntas were represented in as the people’s salvation; Stone believing wholeheartedly

the ploy would result in a loan out of military equipment and forces at no

further expense to the production, thus giving it a big budget look. In the

preliminary stages, Stone also attempted to coax his star, James Woods to fly

into El Salvador with Richard Boyle as his tour guide. The two men, however,

had met earlier at a house party in Los Angeles where Woods took an instant

dislike to Boyle. Furthermore, Woods was a severe germaphobe; the prospect of

suffering a tour of this third world nation under less than hygienic conditions

immediately souring him on the prospect. The last straw for Woods was rather portentous

of things to come; Salvador’s

technical adviser shot at point blank range by rebels while on a tennis court.

After that, Woods understandably refused to go anywhere near the front lines

for the sake of his art. There are really only two ways to regard Stone’s

fervent – if misguided – hope to shoot Salvador

within the country’s war-ravaged borders; either as brave, renegade film-making

of the highest order, or an utterly idiotic daydream of a ‘wild man’ clearly

unable – or at least, unwilling - to factor in the real-life perils he would be

subjecting his cast and crew, merely to follow his dream project down the

proverbial rabbit hole to its inevitable conclusion

Eventually,

Stone and his crew settled on Mexico as a viable alternative. Even then Salvador proved anything but a pleasant

shoot. Extras lying on a hillside, pretending to be corpses, were left to wilt

in the stifling 110 degree heat and humidity for hours; James Woods

inadvertently knocking a fair size rock loose from a pile of debris that rolled

down the hill and struck an extra in the head. Also, Stone frequently came in

conflict with the female agent overseeing the production on behalf of Mexico’s

Censorship Board; chastised for his fairly abysmal portrait of this Latin

American dystopia, riddled in gunfire and strewn for miles with rural blight,

married to the filth of human waste. Meanwhile, in Hollywood Stone and his pet

project were cumulatively being viewed as a firebrand; unfavorably laying blame

for the horrific atrocities squarely at the feet of Ronald Reagan’s

administration. Alas, those expecting a textbook example of how it all came to

pass in the real El Salvador – under the tyrannical reign of Roberto

d’Aubuisson (rechristened Major Maximiliano ‘Max’ Casanova and played with

atypical severity and aplomb by Tony Plana) – would be wise to reconsider a few

points. For Salvador would remain a

tale of extremes, viewed through the photo lens and eyes of a pair of

burned-out grotesques; photojournalist, Richard Boyle (James Woods) and

reformed disc jockey, Dr. Rock (James Belushi).

As such, the

nuggets of wisdom and kernels of fact to be mined from Salvador became more impressionistic; Stone giving us the Cole’s Notes

version of this country’s socio-economic implosion, but (and it’s a big ‘but’)

with his own liberalized slant. At times, this tended to eclipse reality with

only the vaguest hint of verisimilitude. Yet, like Stone’s greatest works, Salvador is exceptionally clever at

mixing up the two. Cast a crew would find no solace; the manufactured chaos

paling in comparison to the animosities mounting behind the scenes. James Woods

became antagonistic towards Jim Belushi; his contempt for Richard Boyle having

already fermented into rank disgust. Woods was clearly unhappy with the working

condition. But he had little – if any – respect for Boyle and only marginally

tolerated Belushi, who frequently tried to lighten the mood by cracking jokes. On

film, this antagonism bode well for the strained ‘friendship’ between Boyle and Rock. Behind the scenes it was a

lethal concoction elevating everyone’s blood pressure – if ambition, to get the

damn thing finished on time and under budget.

At one point,

Woods dramatically announced he was through with Belushi, Stone and the film;

throwing down his gear and marching off the set in the direction of the U.S.

border; Stone chasing after his star in a jeep three miles up a back road to

plead for his return to finish the job. At the same time, the Mexican censors were

ordering Stone to remove half of his ‘set decoration’ garbage to tone down his

representation of the deplorable living conditions which they believed cast a

negative light on their potential tourist trade. Conscious of the fact his $2

million budget could be stretched only so far, Stone begrudgingly complied with

this latter request, mostly to get the censors off his back. Eventually, the

breakneck pace of production and Stone’s meticulous attention to every last

detail, coupled with his added daily responsibilities of playing ringmaster to

these warring temperaments, wore Stone down. By his own admission, he wrapped

production on Salvador emotionally

and physically depleted; even desperate to simply get the footage in the can

and state’s side for the editing process to begin. This too proved something of

a challenge; Mexico withholding the film negative until they believed proper

compensation had been paid. “It was a

nightmare’s nightmare,” James Woods would later remark while shaking his

head.

Our story

begins in Richard Boyle’s seedy San Franciscan apartment; Richard - lazy, half

asleep (or perhaps sleeping off a hangover), leaving his wife (María Rubell) to

grapple with a disgruntled landlord demanding overdue rent money. Oliver Stone

goes to great lengths to setup our first impressions of Boyle as a genuinely

unsympathetic, emotionally cut off and fairly ridiculous screw up. His residence

and his car are variations on a sty; his attempted con of a female police

officer after he’s caught speeding with a suspended license, segueing into our

first introduction of Boyle’s best friend, Doctor Rock; an over-the-hill disc

jockey who hasn’t quite outgrown his penchant for late night carousing. Boyle attempts to find a media outlet that

will fund his expedition to El Salvador to cover the war. He is unsuccessful in

this pursuit, but elects to go down to South America anyway, taking Rock along

for the ride, and using his connections to be reunited with corrupt politico, Colonel

Julio Figueroa (Jorge Luke).

Aside: in the

original cut of Salvador, Figueroa

treats the boys to some ‘hand’ and ‘blow’ jobs courtesy of his small harem; Boyle

– ever the wily diplomatist – finagling some invaluable information from his

old contact while having his ego stroked (other appendages optional). In the

final version we cut to Boyle’s chance meeting with photojournalist, John

Cassady (John Savage); competing cohorts from their old skirmishes in Cambodia;

swapping drinks between shots or shots between drinks…whichever way they choose

to sentimentally recall the atrocities their eyes have seen. More too are in

store for the pair at El Playon; a vacant hillside where the death squads

continue to dump their rotting carrion for the vultures to pick apart. The

Stone/Boyle screenplay trips around, clumsily in fact; and next to San

Salvador’s main cathedral where humanitarian worker, Ramone Alvarez (Salvador

Sánchez) is attempting to help loved ones identify their missing relatives from

mug shots taken after their assassinations. Boyle is seemingly disinterested in

their suffering; using the opportunity to tag along with the guerillas who are

preparing for their counterattack high in the mountains.

Boyle’s failed

attempts to broker favor with the U.S. military overseen by Jack Morgan (Colby

Chester), a cardigan-wearing yuppie pinup analyst for a U.S. State Department,

and Colonel Bentley Hyde Sr. (Will McMillan), leads to a tenuous détente. Boyle

is, after all, a loose cannon; willing to cajole and/or insult to make his

point. He carpet hauls pinup reporter, Pauline Axelrod (Valerie Wildman) as a

‘Park Ave. glamor-puss/blowjob queen’ who’s ‘kissed all the right asses’ to advance

her career as a media darling when, in fact, she’s not much of a reporter and

isn’t really interested in cracking a nail to get beyond the spin put out by

the U.S. State Department. As sweet

revenge, Rock spikes her champagne cocktail with acid; Axelrod, looking

haggard, yet spun, flubbing her lines during a TV broadcast a little later on.

Realizing the

severity of the situation, Boyle plans to get his girlfriend, Maria (the

luminous, Elpedia Carrillo) and her children, including a younger brother named

Carlos (Martín Fuentes) out of El Salvador. At the same time,

he meets up with humanitarian case worker, Cathy Moore and the good sisters,

Stan, Burkit and Wagner. Boyle is flirtatious with Cathy, who doesn’t really take

him seriously. Cathy is, in fact, a valued contact to Ambassador Kelly and

later also becomes something of a point person for Boyle to make his

impassioned plea for a passport to get Maria and her family out of El Salvador.

Boyle is even ready to marry Maria to make the extradition legal. Alas, she

refuses his generosity, partly because she will not be a martyr, but also because

she truly loves Boyle with all her heart. A rift develops in their relationship

when Carlos and Rock are busted as subversives for possession of marijuana;

Boyle bribing the authorities with a gold watch and TV. They let Rock leave.

But Carlos is never heard from again; his badly beaten body later discovered.

In the meantime, Maria convinces Boyle to see Archbishop Romero (José Carlos

Ruiz); a passionate cleric who sincerely preaches for peace and has been marked

for assassination by Major Maximiliano. Romero is publicly gunned down in a

cathedral packed with parishioners; Max appearing before the press a short

while later, supposedly to denounce the mysterious assassin and violence

against the church. To quell the public outrage, Max has Alvarez arrested for

the murder; earmarked as a communist sympathizer and sentenced to death.

Boyle appeals

to Hyde and Morgan to put an end to the fighting by convincing Ambassador Kelly

to pull out all military aid from the ruthless winning side. Boyle’s wish will

be granted – not by any noble intervention, but by a heinous act that incites

the international media to take notice. While on a routine trip to the airport,

Cathy and the sisters are run off the road by Max’s death squad. They are

violently raped at gunpoint before being shot execution-style and buried in

unmarked shallow graves. While Pauline puts a spin on the story; that the nuns

perhaps ran a roadblock and were mistaken as rebels, Ambassador Kelly knows

better, warning Hyde that as of this moment all U.S. aid is being suspended

indefinitely.

As Maria prepares to pack and evacuate her

home, presumably for the mountains, Boyle is called away by Cassady on an

errand to cover the guerillas’ invasion of a nearby town. The guerillas are few

in number – roughly 4000 strong – but hearty in spirit. Despite their crippling

losses, they take over the military stronghold, assassinating their oppressors

at gunpoint, including Max’s army lieutenant (Juan Fernández). Pushed by Hyde

and Morgan into reconsidering his suspension of aid, Ambassador Kelly, who is

being forced into a resignation by the U.S. government, effectively signs the

death warrants for a good many rebels. Tanks, planes and helicopters run

buckshot over the ill-equipped guerillas. In attempting to cover the story,

Cassady is shot in the throat, handing over his film rolls to Boyle before

dying in his arms.

Boyle tries to

smuggle the undeveloped canisters out of the country in his boot; Rock having

paid for forgeries of passports for Boyle, Maria and her children. Alas, the

ruse is discovered by the Junta border patrol, who beat and torture Boyle,

threatening to castrate him. Rock gets to a telephone and demands Ambassador

Kelly intervene. At the last possible moment he does, and Boyle, Maria and her

children are allowed safe passage into the U.S. They slip past customs

undetected. It all seems like smooth sailing, until a routine border security

check stops the couple’s bus as it crosses state lines into California. Boyle

is powerless to prevent the inevitable; Maria and the children are taken away

as illegals while Boyle is arrested for resisting arrest. In the movie’s

epilogue we learn Maria was deported, but rumored to have survived and escaped

to Guatemala.

Almost from

beginning to end, Salvador grips the

viewer with its bittersweet irony: that virtually most – if not all – of the

bloodshed in this war-ravaged territory is needless and could have been avoided

without America’s meddling intervention on the wrong side. At one point,

Richard Boyle confronts Colonel Hyde on this very bone of contention, Hyde

attacking Boyle’s point of view as communist backtalk. “You know…” Hyde informs

Boyle, “…if you were in Vietnam you’d be

working in a reeducation camp pulling turnips.” In what is probably the

best moment of electrically charged dialogue in the film, Boyle comes back with “I never really like turnips very much,

Colonel. And you don't see me applying for Vietnamese citizenship, do you? Is

that why you're here, Colonel? Some kind of post-Vietnam experience? Like you

need a rerun or something? You pour a hundred twenty million bucks into this

place. You turn it into a military zone, so what? So you can have chopper parades in the sky? You let them

close down the universities. You let them wipe out the best minds in the

countries. You let them kill whoever they want. You let them wipe out the

Catholic Church. You let them do it all because they aren't Commies! And that,

Colonel, is bullshit!”

What Boyle

doesn’t get, of course, is that it’s open season on the press in El Salvador;

particularly such loose cannons as he, who have zero cache with their own

diplomatic corps and are equally disdained by the rogue government in charge.

What saves Boyle in the end is not his conman’s shell game; not his ability to

clear-cut a path of logic through this convoluted military operation; nor even

his own wits, diluted by a chronic addiction to TickTack – the country’s 100

proof alcoholic beverage; cheap and lethal in its ability to pickle the human

mind. No, Boyle is brought back from the brink by the one faction he might

never have guessed would stick its neck out for his safety: outgoing Ambassador

Kelly as his final act of amnesty; also by Rock, a man Boyle – and the screenplay

initially treat as his inferior; lacking intelligence and a genuine purpose in

life. Nevertheless, it is Rock who gets

his act together midway through Salvador

(something Boyle never manages to do), and steps into a position of ‘take

charge’ authority. Phoning in his favor to the American Embassy in the eleventh

hour ultimately saves Boyle’s life. Boyle? He remains a screw-up; a social

outcast, incapable of existing without a crisis to buoy him, even in such gruesomely

inhospitable conditions.

The irony is

that while Maria dreams of a better life in America, Boyle lives more honestly

when he places himself at the edge of his own darkest daydream of a destiny – Maria,

Rock and Cassady be damned. The aspiration to be the sort of photojournalist he

can admire; the kind John Cassady already was and might have gone on to be, is

just a diversion for Boyle; a crutch to

convince himself he isn’t as morally bankrupt as he actually is and forever

likely to remain. In Cassady’s absence Boyle greedily elects to smuggle out his

last rolls of film. But would Boyle have

been honest about where this footage came from? Hmmmmm. His failure to

accomplish even this smallest promise prevents us from ever knowing the real truth

about Richard Boyle. It also earmarks him as a pathetic excuse; not only as a

journalist, but also as a human being; exactly the sort deservedly laughed off

by Cathy and vehemently abhorred by Pauline Axelrod.

And yet, James

Woods gives us a disquieting quality of confused nobility in his

characterization; not easily earmarked as humanity, integrity, bravery or even

professionalism. Woods’ Oscar-nominated

performance is, in fact, Oscar worthy because he slices through these complexities,

examining Boyle’s tumult from within, while allowing the audience to see this

struggle brewing. Here is a guy who really doesn’t know – or even ‘want to

know’ how to be a better human being. He just hopes to get by. But he also

wants to be great at it – a con’s con. Defining greatness within such a

mediocre pursuit is as difficult as peeling a turtle. Boyle’s skin, though

seemingly thick at the outset, is actually much more transparent and brittle

once Woods’ gives us this varied portrait of a despicable rogue who doesn’t

even see the validity in legitimately seeking redemption for his own

personality.

Salvador arrives on Blu-ray via Twilight Time’s third party

distribution with Fox/MGM Home Video. It’s a flawed 1080p transfer, particularly

the last reel where the image becomes inexplicable softly focused and

considerably grainier. The scene where Boyle and Maria fake their way through

customs in the U.S. is marred by an unhealthy purplish/green tint and haloing,

also looking decidedly out of focus. Overall, color saturation isn’t quite as

rich as expected; flesh tones wavering between fairly accurate and piggy pink. Contrast

gets milky. But there are some impressive fine details to be had, particularly

in close-ups. Fair enough, Oliver Stone

shot Salvador on a shoestring;

Gilbert Taylor’s cinematography meant to evoke a pseudo-documentarian feel. But

the picture still looks marginally washed out, with a few scattered age-related

artifacts sporadically popping up. We’re given two DTS soundtracks; the original

mono and a new 5.1. Surprisingly, things sound more natural in mono; the

overdubs of dialogue becoming more transparent in the 5.1. Undeniably, Georges

Delerue’s underscore sounds more magnificent in 5.1 DTS. Alas, dialogue and SFX

is center channel anchored. Bottom line: this is an unconvincing stereo

presentation.

TT gives us

its’ usual isolated score option in 2.0 DTS – a superior rendering of Delerue’s

contributions and worthy of a listen. Ditto for Oliver Stone’s astute

observations in an audio commentary – ported over from the old MGM DVD. The

most impressive extra is also a holdover from the old DVD. Into the Valley of Death: The Making of Salvador is an hour-long

chronicle on the making of the film, featuring some fairly astute observations

from Stone, Richard Boyle, U.S. Ambassador Robert E. White, James Woods and

James Belushi. Add to this a half hour of deleted/extended scenes, and a

trailer, and this disc is nicely packed to impress. I just wish MGM had done

more with the transfer.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

3.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

3

EXTRAS

3.5

Comments