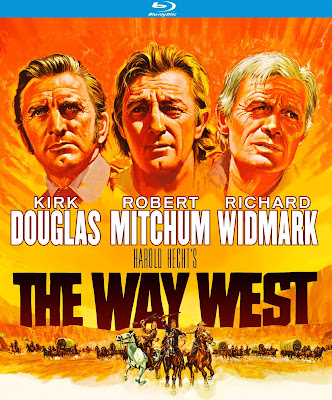

THE WAY WEST: Blu-ray (UA/Harold Hecht Productions, 1967) Kino Lorber

One has to

sincerely admire ‘the pioneer spirit’;

that genuine pursuit of happiness outlined in the American constitution, though

rarely taken to such heart as during the mid-1800’s when the California gold

rush seemed to suggest every living person was on the cusp of becoming a

millionaire. Perhaps marginally blinded by the prospect of overnight riches and

a better life from the only one presently known, the proverbial ‘they’ (comprised of farmers, cowboys,

greenhorns and gamblers, immigrants of every nationality and aspiration) crossed

these rugged terrains from east to west, crisscrossing the nation with their ‘can

do’ aspirations to ‘civilize’ the American west. This naïve sense of entitlement,

alas, was not without many casualties; some, detailed with brutal honesty in

director, Andrew V. McLagen’s all-star spectacle, The Way West (1967). Not since 1930’s The Big Trail had a movie aspired to show the harrowing migration

of a wagon train, lowering its cavalcade – one horse n’ buggy at a time – down a

narrow gorge; just one of the highlights in this occasionally engrossing

western saga with more than a few wild surprises along the way.

The picture

stars three of Hollywood’s heaviest hitters: Kirk Douglas (as tyrannical wagon

train master and former senator, William J. Tadlock), Robert Mitchum (their

lonely, well-traveled and world-weary guide, Dick Summers) and Richard Widmark

(prospector, Lije Evans, afflicted with a wandering heart, much to the chagrin

of his devoted wife, Rebecca – played by Lola Albright). The Way West is as noteworthy for its startling Panavision

compositions, photographed by William H. Clothier. This was the second time

Mitchum and Douglas appeared together in a movie; their first, Out of the Past (1947) pitted as

adversaries after the same woman. Herein, the pair are on the same side – mostly. The Way West also marks the big screen debut of Sally Field as

Mercy McBee whose naïve and fickle heart is restless for sexual adventures. The

screenplay by Ben Maddow and Mitch Lindemann, based on A.B. Guthrie Jr.’s novel,

is somewhat awkwardly cobbled together.

Case in point,

the intrusion of a one-time voice-over narration after we are already fifteen

minutes into the plot, merely to state the obvious – that the migration to

Oregon has already begun – and also, the inclusion of a title tune, composed

(along with the rest of the score, by Bronislau Kaper, with lyrics by Mack

David and sung by a choral called The Serendipity Singers). The ditty is rather

unceremoniously plastered over scenes that once contained exposition between a

few of the central characters, now buried beneath its stereophonic melody. I

suspect, the inclusion of a ‘song’ herein is a nod to 1962’s How the West Was Won – a vastly

superior and sprawling 3 hr. ‘travelogue’ western, shot in the cumbersome

3-strip Cinerama process. At just 2

minutes past 2 hrs., The Way West

can hardly be considered an epic. And, in spots, even as a travelogue, it

falters, as do the performances – given precious little to say or do that does not

connect the plot points together in a fairly rudimentary fashion. Along the way,

we get a lot of superfluous fussin’ and feudin’; the inevitable ‘differences of

opinion’ between our three towering figures of masculinity creating friction

aplenty. There is also an accidental killing, a hanging, and a murder to add

drama to the piece.

Ultimately,

however, The Way West’s greatest

asset is its evocation of that ‘pioneer

spirit’; this drama, far more involving when the three principles step

aside for a moment or two to reveal the harshly lit, careworn and curmudgeonly

visages of all those great-looking extras merely inserted as backdrop. Of these

three, Douglas’ performance is the most genuine, rich in its bitterness and

wounded pride, particularly after the death of Tadlock’s young son (Stefan Arngrim); Douglas, his eyes marred by tears, commanding his slave,

Saunders (Roy Glenn) to literally whip the pain from his body. But Widmark’s

Lije is a chronically unrefined characterization. A devout family man, he

repeatedly and rather selfishly disobeys his wife’s imploring to set-up and

keep the various homesteads they have intermittently called home, merely to

satisfy his itch for adventure; prone to strong drink but loveably so, yet

physically the lesser man in any brawl. This leaves Mitchum’s Summers as the

most fascinating performance to watch; Mitchum, appearing wholly out of fashion

in his goony haircut and buckskin attire, never quite to break free of his

ensconced reputation as a noir-styled anti-hero. Mitchum plays Summers as a man

of even less conviction, though sincerely imbued with high ideals and a

morality malleable to each new occasion as it arises.

Consider that in

minor parts as Preacher Weatherby, the sexually frigid/and later - utterly

insane Amanda Mack, unnamed stoic Sioux chief, and finally, love-struck Brownie

Evans, bug-eyed Jack Elam, fiery Katherine Justice, passionate Michael Lane,

and introspective Michael McGreevey are oft’ more credible and memorable than

all the fireworks and fisticuffs afflicting the principals, as well as delaying

this fictional party’s arrival to their destination. The Way West was photographed amidst some truly inspired topography

in Arizona and Oregon, including Crooked River Gorge for the penultimate

carriage-lowering descend. Breathtaking in its scope, and fairly ambitious in

its effective use of matte paintings to depict a harrowing thunder storm, The Way West rises or falls on its

ability to be appreciated as yet another glossy western yarn, more interested

in melodrama than effectively evoking many of the harshest realities afflicting

the original pioneer wagon-trains.

Our story begins

with the introduction of our three main characters: former U.S. Senator William

Tadlock, having departed his constituents in Missouri, circa 1843, headstrong

and determined to lead a wagon train of dirt farmers and dreamers west on the

Oregon Trail. Widowed, bitter and as ever resolved to make a success of this

terrible journey, Tadlock takes his young son and slave along for the ride. Seeking

out former tracker and guide, Dick Summers, who lives obscurely in the

wilderness near the river, Tadlock goads the reluctant Summers into accepting

the work, already recognizing his foot-dragging is predicated on the knowledge

he has slowly begun to lose his eye-sight, rather than any lingering angst over

the untimely death of his own Sioux bride during childbirth. The wagon train is

joined by farmer. Lije Evans, his wife Rebecca and their 16-year-old son,

Brownie. Also, among this lot are newlyweds, Johnnie (Michael Witney) and

Amanda Mack (Katherine Justice) and the McBee family; Mr. (Harry Carey Jr.),

Mrs. (Connie Sawyer) and their sexually-aware, though queerly as naïve teenage

daughter, Mercy.

In short order

we learn of Brownie’s true love for Mercy – not to be reciprocated, alas; also,

Amanda’s frigidness toward her strapping husband, and finally, Mercy’s

infatuation with Johnnie. At the outset, spirits run high. Despite Tadlock’s

brutish determination to bully everyone onward, and being at least partly

responsible for the premature death of a terrified merchant, Mr. Cavelli (Nick

Cravat), whose weighted money belt drags him under after his carriage overturns

in a heavy undertow while crossing the river, the mood among this aspiring cavalcade

is mostly positive. Also discovered as a stowaway is Preacher Weatherby,

clinging to the undercarriage of the Evans’ covered wagon. Ordered by Tadlock

to return home, Weatherby instead offers his services as a man of the cloth and

is embraced by the settlers who declare “we

need religion.”

Unable to glean

any real advice from his own father regarding women, Brownie relies on Summers

to guide him in his romantic pursuit of Mercy. Summers confides that a woman

must be coaxed into love, and offers Brownie to borrow a ‘good luck’ necklace

made of turquoise, the only possession he retained from his late wife. The introspective Brownie is deeply honored. After

the wagon train passes through a hellish thunder storm and, a stifling days’

worth of intense heat, they set up camp for the evening near a clearing; still

untainted in their optimism. Eavesdropping on the Mack’s marital problems,

Mercy elects to set her cap for Johnnie, who is at first incensed by her

inquisitiveness, but later will take full advantage to seduce her by the river.

Regrettably, Amanda suspects what has occurred between the two.

The wagon train

encounters a Sioux tribe after Brownie, while carving his initials into the

side of a granite wall, is momentarily taken prisoner. Summers narrowly averts

this catastrophe by taking the Chief’s youngest son hostage, fairly trading

Brownie’s life for the boy’s safe return. Later, the Chief demands tribute from

the settlers – who trade their alcohol to maintain the peace. At the late night’s

revelry, Johnnie and Mercy sneak off to make love. Afterward, however, Johnnie

tells Mercy he can never be hers. She runs away ashamed and Johnnie mistakes the

youngest of the Chief’s seven sons, disguised in a dark fur skin and rummaging

through the dense foliage, as a wolf about to pounce. He shoots the child dead.

Haunted by the reality, Johnnie nevertheless keeps the incident to himself,

retreating to his wagon.

Discovering the

boy’s remains, the Chief prepares the body in ceremonial attire and parades it

past the settlers, shocked and reviled by the spectacle of this powdered

corpse. Demanding justice for the killing, Tadlock reasons the only thing that

will likely spare the rest of their lives and satisfy the Sioux is a show of

force; nothing less than a public hanging of the man responsible for the crime.

In lieu of anyone admitting to as much, Tadlock offers up Brownie as a human

sacrifice. He then calls upon every man in possession of a rifle to step

forward. Unable to see an innocent hanged for his crime, Johnnie reveals the

truth to all. Makeshift gallows are erected and Johnnie is hanged by the neck until

dead by Tadlock, garnering the Chief’s satisfaction. The Sioux tribe retreat

into the hills, leaving the wagon train to proceed onward to its destination. Sometime

later, Mercy confides in Brownie she is carrying Johnnie’s illegitimate child.

As the wagon train arrives at the Hudson Bay outpost, Fort Hall, Brownie

proposes marriage to Mercy, vowing to raise the unborn child as his own. Although

she confesses to having no love for him – as yet, Mercy agrees to this sham

wedding; the couple nearly called out by Amanda, who is bitter and determined

to expose her husband’s infidelities.

Instead, Brownie

lies to having seduced Mercy and made her pregnant. The outpost’s manager,

Captain Grant (Patrick Knowles), although startled by the news, prepares the ‘happy

couple’ an elegant feast to mark their celebration; Weatherby officiating the

ceremony as the Evans and McBees tearfully look on. Tadlock’s attempts to

disentangle his party from a prolonged stay at Grant’s request proves feeble. His

settlers are weary. Besides, the fort offers every luxury they could possibly

want. Alarmed after overhearing a conversation between some of his party and a

drunken prospector trying to lure his members to the gold nugget-rich hills of

California, Tadlock lies to Grant; suggesting one of his troop is stricken with

the small pox. Grant is appalled. The last time the plague hit it wiped out a

considerable number of the fort’s inhabitants. Tadlock and his troop are immediately

cast out of Fort Hall; most, never realizing the reason for their hasty

departure.

The next afternoon,

Tadlock’s party encounters a terrible stretch of desert. Summers suggests they

make their way around its perimeter; a delay of up to a week. But Tadlock is determined

to drive on to the brink of exhaustion. Several days later, even he can see the

grotesque error of this impromptu decision. Tadlock further compromises their

spirits by forcing his people to divest themselves of all their worldly –

though needless, and weighty possessions – lest they bog down and waste the

horses. Tadlock and Lijes enter into a display of fisticuffs over Lijes refusal

to surrender Rebecca’s prized grandfather clock. Indeed, it remains the one asset

from her dowry she has taken on all their trips. Tadlock ruthlessly tosses it

into the sand, his pitiless rage perhaps predicated more on his earlier romantic

overtures to Rebecca denied, behind her husband’s back. Tadlock ruthlessly

pummels Lijes, who nevertheless regains the upper hand in the end, narrowly

beating Tadlock unconscious before being subdued by Summers.

The settlers,

their livestock and horses are now physically drained and in grave danger of

succumbing to starvation and/or dying of thirst. Miraculously, Summers leads this

beleaguered entourage straight to a sump and adjacent field rich with greenery

on which the animals might graze. Tragically, in their race to the sump, the

horses pulling Tadlock’s carriage become startled. Tadlock’s son is jostled from

his mount, the carriage overturning and crushing the boy to death. Unable to

reconcile his pain after the child is buried in an unmarked grave in the sand,

Tadlock orders a startled Saunders to whip the anger from his body and mind.

Having assumed charge of the expedition, Lije is encouraged to show Tadlock

compassion, Rebecca revealing the plans Tadlock had for their new settlement in

Oregon. The men agree to work together and see their communal dream to fruition.

Arriving at a perilous gorge with nowhere to go but down in order to link up with

the road in the Willamette Valley, Tadlock has a makeshift trestle constructed

to lower the wagon train, piece by piece, to the valley floor.

The first

attempt is disastrous, and Mr. Turley (Paul Lukarther) plummets to his death. After

a period of mourning, the settlers begin again and, one by one, they are

successfully lowered to ground level. The second to last is Tadlock, who buoyantly

declares the dream they have all shared for so long is nearing its destination.

Regrettably, everyone has forgotten about Amanda Mack. Never having forgiven

Tadlock for publicly hanging her husband, and since driven mildly insane with

jealousy over Johnnie’s affair with Mercy, Amanda severs Tadlock’s lifeline as

he begins his descend into the valley. He plummets to his death as the settlers

look on; an ebullient Amanda declaring from the top of the cliff they are all

free from Tadlock’s tyrannical hold at long last. Burying Mr. Turley and

Tadlock in adjacent graves, the settlers prepare to follow the river on its

last length to Oregon. Only now, they will have to make their peace and purpose

without Summers’ help. He intends to setup housekeeping in parts yet unknown, Lije

imploring him to reconsider. Summers’ rapidly dwindling eyesight will soon prevent

him from being self-sustainable. Although he knows this, Summers has decided to

make his peace alone; through with the great migration; his one desire, to live

the rest of his years for himself/by himself. Lije, his family and the rest of

the settlers board makeshift rafts and sail them down the river beyond the

canyon; their destinations unknown as our journey alongside them draws to its

close.

Despite its

groundswell reprise of the title track as the camera follows the Evans floating

down river, The Way West’s finale is

rather unfulfilling. At the very least, it seems grossly unfair to have encouraged

the audience to invest in the plight of these men and woman without seeing any

of them through to their promised land. Yes, the ending does justify as a somewhat

sad-eyed generational epitaph to this settler class, responsible for ‘civilizing’

the American west. But it also concludes on a note of open-ended

dissatisfaction in absence of seeing their journey through. Along with these

robust and hearty individuals, we have come much too far to remain so very far

away from this dream remembered; the denouement, empty-hearted at best. The

merits of the movie are mostly found in its startling and stark visual style.

The narrative, however, is weak and bumblingly episodic. There ought to have

been more ‘meat on the bones’ as it were; more involvement and interaction

between these characters, more details revealed about them to invest us in

their sacrifices. Alas, what we get are cardboard caricatures of western

archetypes best found elsewhere in other Hollywood-ized western movies made

long before and since The Way West.

Owing to

limitations in MGM/Fox’s existing archives, and afforded virtually no

restoration in readiness for this 1080 release, Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray transfer

is a mixed affair at best. The first few reels are very impressive; the

Panavision canvass extolling the virtues of William H. Clothier’s

cinematography in a palette of rich, bold colors, with stunning clarity marred

only by sporadic hints of edge enhancement. The picture – literally – is not

quite as promising in the reels immediately following the party’s departure

from Fort Hall. I suspect, although I have no way of knowing, these scenes have

been derived from either a second or third generation print master or perhaps a

poorly contrasted dupe. Either way, and almost immediately, we completely lose fine

detail; the palette becoming extremely muddied with blown out contrast levels. Herein,

a barrage of age-related artifacts is also present and, in spots, thoroughly

distracts. The image does snap together again before the final fade out; but it

is sporadically pleasing from here on in; toggling between the near-perfect

quality of its earliest reels as previously described and the bizarrely

uncomplimentary viewing experience only just mentioned. The 5.1 DTS audio is

adequate – mostly – but has a few anomalies too; the stereo rendering of the

title tune suffering from problems in spatial separation with voices heard bouncing

from left to right to center channels – not directionalized – but awkwardly

cutting in and out. The only extras are a badly worn theatrical trailer and

several others for more Kino Lorber western-inspired product. Bottom line: The Way West is a movie for die hard

fans of Mitchum, Douglas or Widmark. Having seen it once, I cannot anticipate

ever wanting to revisit it again, particularly with such an imperfect transfer.

Regrets.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

3

VIDEO/AUDIO

3

EXTRAS

0

Comments