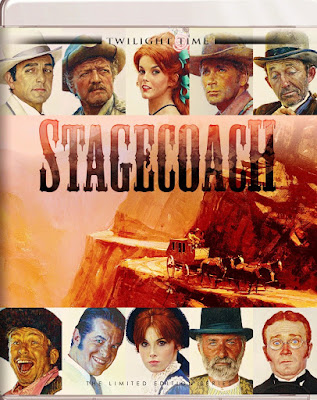

STAGECOACH: Blu-ray (2oth Century-Fox, 1966) Twilight Time

John Ford’s

exhilarating reboot of the Hollywood western, Stagecoach (1939) featured a career-defining role by John Wayne as

the Ringo Kid who, in the intervening decades, would become something of Ford’s

good luck charm. Gordon Douglas’ glossy Cinemascope

remake of 1966 adds visual girth and color by DeLuxe to the milieu, but

minimizes this character’s importance by casting the relatively unknown and

nondescript (and, regrettably, to remain so) Alex Cord in the crucial role.

Cord, who has worked steadily in pictures and on television, has nevertheless

remained something of a forgotten man in the pantheon of greats. It’s a shame

too, because the lanky, blue-eyed and butch Cord in this Stagecoach offers up some good solid acting and is afforded some of

the best scenes in Joseph Landon’s reworking of Dudly Nichols original

screenplay (all of it very loosely

based on 19th-century French writer, Guy de Maupassant’s Boule de Suif). Cord has an

amiable gal to play off; henna-haired firebrand, Ann-Margret as the fallen

woman, Dallas (originally characterized by a sullener Claire Trevor).

Ann-Margret can slink and coo. She can even exude va-va-voom sex appeal without

seemingly trying. But the role of Dallas demands something more, and this

intangible ‘extra’ we never get. It is perhaps a pointless

exercise to draw comparisons between the two versions of Stagecoach, as Landon and Douglas have conspired herein to tell a

slightly different story with only a faint whiff of familiarity, and, narrowly

a glimmer of the elusive spark of screen magic that made Ford’s original such a

genre-defining masterpiece. Douglas’ reboot uproots the action from Ford’s

beloved Monument Valley to the lush green wilds of Caribou Country Club Ranch in

Nederland, Colorado. Stagecoach ’66

is extraordinarily well-endowed in its ensemble: Bing Crosby, as weather-beaten

booze-hound and disgraced physician, Doc Josiah Boone; Red Buttons, the

ever-fretful alcohol peddler, Peacock; Van Heflin (Marshall Curly Wilcox), Slim

Pickens (Buck – the stagecoach driver), Bob Cummings (Henry Gatewood), Stefanie

Powers (Mrs. Lucy Mallory), Michael ‘Mannix’

Connors, as the noble gambler, Hatfield, and, Keenan Wynn, as notorious

cutthroat, Luke Plummer.

Again, the

casting is solid. Alas, their presence is barely felt – an oddity, indeed –

and, in hindsight, a real letdown, especially given their collective mega

wattage star power. Of the lot, Cummings and Crosby (the latter, in his last

appearance in a major motion picture) get the lion’s share of run time; Crosby,

notably doing nine extra minutes of the wounded lush that won him an Oscar for The Country Girl (1954), and Cummings, refreshingly

– and rather convincingly – cast against his usual squeaky-clean and congenial

good guy, as the perversely motivated and nerve-racked amateur thief of his

father-in-law’s bank roll. Perhaps the biggest sin committed by this remake is

that, despite its many virtues, including some utterly gorgeous outdoor

cinematography by William H. Clothier, a score by Jerry Goldsmith, and

memorable end titles, expressly conceived for the screen by renown American

painter and illustrator, Norman Rockwell (whose likenesses truly capture the

essence of each character), this Stagecoach

remains just passable and even fails in its most exhilarating moments to

distinguish itself as grade ‘A’ entertainment.

If the picture were dull, we could easily dismiss it. If it were

clumsily scripted, badly played, poorly shot or dramatically insensitive to the

plight of its characters, this too would classify it as a complete turkey and

write-off. The fact Douglas and the movie endeavor at every turn to be better

than they ultimately are, the sheer investment of energies conjointly expended

in toil to create a classic, yet somehow still missing the mark, is what I

personally find so frustrating here. There are nuggets of greatness to be

unearthed. Ray Kellogg’s matte special

effects during a raging thunderstorm are impressive, as is Douglas’ staging of

the penultimate showdown between the stagecoach travelers and Crazy Horse and

his marauding Sioux warriors; the camera, fast navigating through a heavily

wooded stretch of winding path before taking to the skies for a startling

bird’s eye view of this thwarted retreat. Herein, Alex Cord actually performs

the iconic ‘leap’ across the galloping stagecoach stallions after Buck, wounded

by gunfire, loses control of the reins (a stunt done in long shot in Ford’s

original, to mask stuntman, Yakima Canutt subbing in for John Wayne).

The plot remains

similar if not exact to the 1939 original. After some breathtaking overhead

shots of the tall pines at Colorado’s State Park, we settle into a small

outpost where a motley band of travelers is preparing for their departure on

the noon stagecoach. Just prior to our introduction to this cast, we bear

witness to a very bloody aftermath; remnants of the U.S. Cavalry, bludgeoned,

beaten and left to bake in the harsh sun by Crazy Horse’s Sioux. In town, as yet, the occupants have no

inkling of this carnage. At the saloon, hard-hearted gambler, Hatfield is

preparing to take his latest card-playing cohorts to the cleaners. At the bar,

Doc Boone is indulging in strong drink, casually admiring the attractive

prostitute, Dallas, dancing with a drunken trooper (Bruce Mars). Their goofy

gavotte is interrupted by a slovenly Lieutenant (Brett Pearson), who attempts

to break up the pair and take Dallas for his own. She resists and the trooper, with

misguided chivalry, tries to subdue the Lieutenant with a knife. He succeeds in

mortally wounding the man, but not before the Lieutenant crushes the life out

of him. Seemingly responsible for the death of two men, investigating the

killings, Captain Jim Mallory (John Gabriel) orders the saloon keeper, Jerry

(Hal Lynch) to rid his establishment of its undesirables or he will do it for

him. Under duress, Jerry instructs Dallas to pack her things – perhaps, just as

well.

Meanwhile, in

another part of town, amateur thief, Henry Gatewood is preparing to make off

with his with father-in-law, Mr. Haines’ (Oliver McGowan) $10,000 bank roll;

entrusting Henry with papers, supposedly to be delivered in Denver for the new

merger. Gatewood’s fussbudget wife, Elouise (Muriel Davidson) demands Gatewood

delay his trip; not because rumors abound the path ahead is populated by

ruthless Indians and therefore unsafe – no

– but to keep her husband apart from the wiles of ‘that woman’ – Dallas – whose reputation precedes her. As the

stagecoach makes ready for its departure, Marshall Curly Wilcox is forewarned

by a cavalryman of an ominous silence at one of the army’s outposts. Buck

nervously pleads for the stage to remain in town until confirmation comes

through regarding their safe passage. But Curly will have none of it. At the

bar, Doc Boone befriends Peacock – a fastidious liquor peddler whom Doc rather

humorously convinces to be unwell, promising a possible cure if Peacock takes

his medical instruction under advisement. In the meantime, Boone continues to

lighten Peacock of his case of ‘free’ samples. In another part of town,

Hatfield grows protective of the reserved Lucy Mallory, pregnant with child and

on her way to be reunited with husband, Capt. Mallory at Cheyenne. Despite

Buck’s renewed protestations regarding the Sioux, the stage departs on time and

with all on board.

Not far out of

town, the passengers encounter the Ringo Kid, wanted for murder. As Ringo and

Curly are ‘old friends’ he naturally assumes Curly will cut him some slack in

his pursuit of Luke Plummer and his two sons, gunslingers Ike (Ned Wynn) and

Matt (Brad Weston). Instead, Curly orders Ringo to surrender his rifle, placing

him under arrest. As the stage prepares to leave, Doc Boone has a faint glimmer

of memory he and the Kid have met before. And so, they have, when Ringo was

just a boy. Boone confuses his recollection of setting the Kid’s arm after a

terrible break in childhood. Ringo corrects this reminiscence, explaining it

was his younger brother on whom Boone plied his physician’s skills. Amused,

Boone casually inquires whatever became of Ringo’s brother, to which the Kid

rather coldly informs that both his brother and father were murdered by the

Plummers. Late afternoon, the stage

pulls into a respite for food and to let the horses rest. Nervous his theft

will be found out prematurely, and eager to put as much distance between him

and the town, Gatewood encourages Curly not to delay for too long. Meanwhile,

Ringo and Dallas become acquainted. He refers to her as ‘a lady’ – a compliment

that backfires and raises her dander, as she believes he is being fresh. He

makes no apology for the reference, but reiterates his sincerity, which is

genuine. Dallas is smitten, but denies her feelings for Ringo. A whopper of a

storm strikes up along a steep and narrow mountain pass. Ringo successfully

leads the horses down the tight mountain bend, but is nearly trampled

underfoot.

Before

nightfall, the stage arrives at the decimated U.S. Cavalry outpost, finding it

strewn in dead bodies – the undeniably handywork of the Sioux. Against Curly’s

polite objections, Lucy insists on thoroughly inspecting the camp personally,

to know for certain whether or not her husband is among its casualties. Having

discovered Captain Mallory not among the deceased is a relief. Gatewood cruelly

complains that they must leave the outpost. But Lucy stands her ground. She

will not depart until every last butchered man is laid to rest in a proper

Christian burial. And so, the digging begins. Hatfield confides in Lucy, he

served under her father during the Civil War. This burgeoning friendship is cut

short when Lucy collapses and goes into labor. Unable to move her, Curly elects

to remain at the outpost, ordering Doc Boone to sober up and deliver the baby.

Boone forces himself to be ill on black coffee heavily laced with salt. He then

orders Peacock to pour alcohol over his hands, informing the others of its

sterilization properties. Before nightfall, Lucy gives birth with Dallas and

Doc Boone at her side. As twilight falls, Dallas confronts Gatewood as he is

preparing to sneak off with one of the horses. He lies about his intentions to

take her with him to Denver. Dallas isn’t buying it and even threatens to

expose the truth to the others. Instead, Ringo interrupts the pair, forcing

Gatewood to go back inside.

Ringo confesses,

he is in love with Dallas. He also tries to get Dallas to see what her future

could be if she would only agree to come with him. Hardened by her years as a

whore, Dallas again fights her purer feelings towards Ringo; their passionate

debate, intruded upon by Curly, who orders them both back into the main house.

The next morning, Dallas smuggles Ringo’s rifle into the kitchen, encouraging

him out the back door and onto a horse. He must ride before Curly discovers he

is missing. Alas, Curly catches the pair in the act, just as Ringo has mounted for

his escape. Only now, Sioux are on the hillside, amassing for another attack.

Curly orders everyone onto the stage; Buck, making haste away from the

onslaught. Momentarily, a ray of hope appears as Curly sees cavalrymen fast

approaching from the rear on horseback. However, as the contingent draws

nearer, Curly suddenly realizes it is Sioux, disguised in uniforms stolen from

the outpost. Ahead of the stage, another faction of the tribe in traditional

garb emerges from the forest, forcing Buck to take an alternate route through

the woods. Jostled over rough terrain, the stage drops one of its wheels.

Trapped, Curly orders everyone from the coach to take cover behind the rocks,

arming even the Kid with guns and rifles to defend themselves. At first, they

manage rather skillfully to hold off the Sioux. However, the tribesmen regroup

and again charge the rocks where everyone has taken refuge. In this second

assault, Hatfield is mortally wounded.

Nevertheless,

Curly and the rest are spared. Suffering grave casualties, the Sioux retreat.

The stagecoach, with a large wooden branch affixed to its back chaste, lumbers

into town under the cover of night, only to find it nearly deserted. Inquiring as to this curious silence, Curly

is informed by the Cheyenne Wells Fargo Agent (Walker Edmiston) the Plummers

are in town – having taken over the saloon for three whole days of drunken

revelry. Ringo implores Curly to let him have his day with the men who killed

his family. Instead, Curly handcuffs Ringo to the stage, handing the keys to

the agent. Now, Curly is informed by the agent of a wire just come through,

calling for Gatewood’s arrest. Determined

to apprehend Gatewood and also force the Plummers to leave town, Curly

confidently saunters off to the saloon, beaten to the chase by Gatewood, who is

presently attempting to bribe Luke Plummer into accepting his offer of $1000 to

escort him to Denver.

Curly orders

Luke to hand over Gatewood to him. In reply, Luke sadistically has one of his

boys, Matt, knee-cap the Marshall with two gunshots to the legs, tossing his

crippled body into the dust just beyond the saloon. Witnessing the crime, Boone

takes matters into his own hands, holding the agent at gunpoint and ordering

him to unlock Ringo’s restraints. Ringo proceeds to the saloon. Rescuing Curly

first, Ringo next makes short shrift of Ike – hiding in an upstairs window – then

Matt, whom he drops with a kerosene-lit chandelier. The flammable liquid catches

fire quickly and sets the saloon ablaze. Luke rather proudly taunts the Kid from

a darkened upstairs hall, promising he will soon meet the same fate as his

murdered family. Instead, Ringo manages to get off two shots, killing Luke as

the saloon goes up in flames. Narrowly escaping the blaze, Ringo is reunited

with Dallas. Forfeiting the reward for Ringo’s capture, Curly decides to look

the other way, ordering Ringo to take Dallas and head for the hills with all

speed, presumably to find their ever-lasting happiness together. We fade out as

their carriage pulls from view; the Norman Rockwell inspired end titles,

celebrating the ten principle players.

Stagecoach is hardly a memorable entertainment. And yet, it

remains enjoyably diverting, and, downright compelling in spots. Douglas’

direction cannot hold a candle to John Ford. Nor is there any inkling of doubt which

of these incarnations is beloved and/or preferred by most movie buffs. Still, Stagecoach ‘66 is solidly constructed,

with production design by Herman A. Blumenthal and Jack Martin Smith, shooting

the town sequences on the Fox backlot, interiors on soundstages, and the rest,

on location in Colorado. Alex Cord, while no John Wayne, offers an intelligent

and introspective performance as the Ringo Kid. Conservatively, he never

aspires to copy Wayne, either in mannerisms or deportment, and manages to offer

up something fresh – if not nearly as iconic. The outstanding performance

herein is likely Bing Crosby’s devilishly humorous Doc Boone. In Ford’s

original, this role was played with striking self-pity by well-known character

actor, Thomas Mitchell who, in 1939, could chalk up screen credits in three

colossal pictures: Stagecoach, Only Angels Have Wings, and, Gone with the Wind! Wow! What a

pedigree! Crosby’s Boone is less downtrodden and more of a beloved and

bedeviled stoner. He deviously preys upon Peacock’s hypochondria, getting the

neurotic to gargle and meditate his way back to good health; an enjoyably

obtuse diversion, lightening the mood of this otherwise dramatic tale. If only

this version of Stagecoach were

about these two sillies, it might have had something better to offer an audience

on this second time around. Van Heflin and Slim Pickens do their utmost to keep

the action moving. Bob Cummings is perversely watchable as the unrepentant

crook, and - in the final reel - Keenan Wynn is a formidable baddie. But the non-descripts kill the mood. Ann-Margret (top-billed), Stephanie Powers,

and, Michael Connor are forgettable filler. In the last analysis, Stagecoach misses its mark because

there are too few weary passengers on board for whom we simply lack an invested

interest to see arrive safely to their destination.

No one can

accuse Stagecoach – the Blu-ray – of

missing its mark in hi-def. This transfer, derived from restored elements, is

utterly gorgeous. While a few blemishes remain, these are minor and wholly

excusable. This 1080p offering pops with rich, bold and fully saturated colors.

Fresh tones are natural in appearance. The DeLuxe palette favors lush and

vibrant greens, with the occasional splash of sunshine yellows, royal blues and

fiery reds. A modicum of film grain looks very indigenous to its source. Truly

there is nothing to complain about here. We get a 2.0 mono mix that has been competently rendered. Apart

from Twilight Time’s usual commitment to providing us with an isolated score,

showcasing Jerry Goldsmith’s wonderful music, plus, an audio commentary from

Lee Pfeiffer and Paul Scrabo, newly recorded for this release,

there are no extras. Bottom line: Stagecoach

is a good solid western – but not nearly as brilliant as its predecessor. The

Blu-ray is near perfection and well worth your coin. Judge and buy accordingly.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

3.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

4.5

EXTRAS

1

Comments