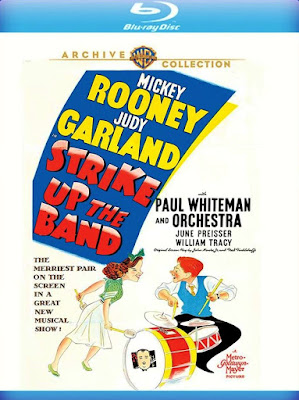

STRIKE UP THE BAND: Blu-ray (MGM, 1940) Warner Archive

The perfect storm of creative geniuses conspired to

make Strike Up The Band (1940) a patriotic flag-waver. Indeed, MGM spent

lavishly to best their efforts on the previous year’s Babes in Arms

(1939), the movie that launched the ‘backyard musical’ with two of its

biggest stars – Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland – at the helm. As then, this new

project was overseen by producer, Arthur Freed, to whom Metro’s studio

chieftain, L.B. Mayer had literally thrown open the gates and granted creative

freedom. It is not overstating the obvious to suggest Mayer adored Freed as few

– even, from his inner circle; his trust, aligned with Arthur’s zeal for musicals

steeped in homespun mantras affiliated with Mayer’s own desire to produce

quality family entertainment. Following the megawatt success of Babes in

Arms, Mayer drew up a new contract for Freed, one to further his ability to

go after any property he deemed rife for exploitation and profit. Mayer also gave

a sizable increase to Freed’s salary, putting him in line with the

well-ensconced producers on the backlot. Freed’s newfound autonomy caused him

to go on something of a creative binge in 1940, pursuing such legendary artists

as George M. Cohan, and, George and Ira Gershwin. Alas, Freed’s desire to

produce an updated version of the collegiate musical, Good News was

politely dismissed by Mayer who, believing the world had grown a little wearier

with the advancing European conflict, instead encouraged Freed to go after the

Gershwin’s Strike Up The Band – a property dating all the way back to

1927!

In crafting a confection worthy to follow up Babes

in Arms, Freed literally threw out all of Strike Up The Band’s

original stagecraft and songs, except its title tune, instead, electing to work

on a ‘brand new’ score to compliment a completely original story. For popularity’s

sake, Freed turned to Paul Whiteman, whose pie-faced visage, and, a rather

unprepossessing style in conducting did little to impact his staying power as

one of the premiere ‘big band’ leaders of his generation. With the onset of WWII, ‘swing’ – effectively,

the ‘second coming’ of jazz, with its bold and brassy sound – was king at the

box office. Meanwhile, in the director’s chair was none other than Busby

Berkeley, that zeitgeist to have established an unmistakable ‘look’ for the

Hollywood musical over at Warner Bros. throughout the 1930’s. And while

Berkeley’s tenure at MGM would prove the old master was not yet without a few

schemes up his sleeves, on Strike Up The Band, Berkeley forewent his

usual zeal for creating geometric configurations out of his dancers, choosing

instead, an intricate framing device; his two stars, Garland and Rooney, always

made the centerpiece of every production number. While Berkeley reveled in

concocting his most spectacular musical vignettes to date, Freed approached Yip

Harburg, whom he hired as an associate, but also to broker an introduction with

Vincente Minnelli – a self-taught sketch artist, window dresser, and, set decorator,

presently working in New York. Minnelli had already been out to Hollywood, but

had found the experience so distasteful he had already soured on the idea of

ever returning to the West Coast again. To assuage his fears, Freed offered

Minnelli precisely the autonomy he craved to create ‘something spectacular’ for

the number, ‘Our Love Affair’. And while Freed desperately wanted

Minnelli to join his ‘unit’ at MGM, he also lured Minnelli to reconsider by

providing him with a ‘no strings attached’ option to simply walk away from

everything, if the work environment was not to his liking. Naturally, this all appealed

to Minnelli who eventually came up with an inspiration for Freed’s ‘problem’

number; an idea, largely lifted from a Life Magazine article in which

fruit was made up to look like musicians. In Minnelli’s case, the fruit also

became animated and played musical instruments.

Strike Up The Band is perhaps the perfect ‘war-time’

movie musical in that its patriotism springs to life seemingly by accident, the

new score forgoing that ‘heavy-handed’ approach to sentiment, and, Gershwin’s

celebrated ‘hit tune’ originally written in 1927, and later tweaked to become

UCLA’s football ‘fight song’, herein, again, slightly reworked to conform to

the dimensions of the new plot as outlined by John Monks Jr. and Fred

Finklehoffe. By 1940, Mickey Rooney was one of MGM’s highest paid stars – his versatility

seemingly to know no bounds. While Babes in Arms had continued Rooney’s

upward trajectory as the studio’s #1 teen talent, the picture – coupled with

Judy Garland’s other star turn in The Wizard of Oz (1939) literally made

her an instant A-lister at the studio. It had taken 4-years to mature Garland

into this ‘suddenly’ bankable titan, mostly because until 1939 MGM had attempted

to simply fit her into movies neither entirely hers to command (employing her as

a ‘specialty’), nor ideally suited to her unique qualities. But from 1939 onward,

Garland would rarely be caught ‘between films’, her work schedules overlapping,

leading to an even more insidiously chronic dependency on pills to see her

through. Alas, the strain was already proving too much. While appearing on ‘the

circuit’ to promote Babes in Arms, Garland was so overworked she

suffered a momentary collapse, necessitating her withdrawal from the breakneck pace

– for two days! Possibly, neither Mayer nor Arthur Freed had any time to notice

their star was already spiraling out of control. They were much too busy preparing

the next ‘Garland’ picture; Freed, as invested in a top-heavy spate of Broadway

to Hollywood hybrids and new-to-screen musical properties already in

development. Of these, Good News had seemed like a viable option; a

home-spun college-themed musical derived from a Broadway hit and an early

1930’s talkie (later, to be remade as a glossy 1947 Technicolor classic,

co-starring June Allyson and Peter Lawford). But the evolution of Good News

into a Garland/Rooney follow-up did not go smoothly; Freed, eventually losing

his patience and interest, abandoning the project altogether, even as he was

putting the finishing touches on Andy Hardy Meets Debutante (1940, and, also

co-starring Rooney and Garland).

It should be noted, Strike Up the Band – the

movie – bears no earthly resemblance to the Gershwin show, jettisoning its

witty and timely banter and barbs about social mores and politics in favor of

yet another ‘come on, kids…let’s put on a show’ featherweight fluff

scenario. This time, the Monks/Finklehoffe screenplay has Rooney cast as

amiable drummer, Jimmy Connors, who manages the nearly impossible feat of

taking his high school band national, achieving early success, only to reach a

stumbling block when he discovers famed band leader, Paul Whitman is hosting a

radio program in search of the ‘stars of tomorrow’. Lacking the necessary funds

to enter the competition, the outpouring of support shown ‘the kids’ via

some ambitious fundraising is further thrown into a tailspin when Jimmy must

choose between helping a friend in need of a costly medical procedure or

selfishly to use the moneys collected to gratify his own ego. After some consternation,

Jimmy makes the right decision and is rewarded when the band is invited to

perform at the competition anyway – and – rather predictably, wins it hands down.

Strike Up the Band’s plot is no better than a hundred others. But the

picture is immeasurably blessed to have the Rooney/Garland chemistry at play.

Apart from its rousing finale, the picture is noted for the Roger Edens/Arthur

Freed song, ‘Our Love Affair’ – immediately becoming a standard on the

hit parade. The other standout, Nell of New Rochelle is a delicious

lampoon of Victorian era slum prudery, for which Garland and Rooney proved

equally adept at mimicking this ‘simpler time’.

Even before the release of Strike Up The Band, rumors

abounded Rooney and Garland might be on their way to a real-life romance. Until

his dying day, Rooney emphatically insisted there was never any real ‘love

affair’ between them. “We were more like brother and sister,” he

confided in one of his last interviews, “I said to her, Judy, honey…you’re

the best in the world. Now, go out there and show them what you got.” Given

that the picture is directed, practically in its entirety, by Busby Berkeley, his

contributions herein are very un-Berkeley-esque. The musical numbers are

delightfully executed, but no more so than your average, lavishly appointed MGM

musical programmer from this vintage. The exception here is ‘La Conga’ –

originally written by Roger Edens as a little trifle to be trilled by Garland. Instead,

Berkeley saw it as a huge production number, employing scores of dancers and Whitman’s

orchestra to extend the minute-and-a-half ditty into a spellbinding 11 ½ mins. of

intricately choreographed movie magic. Garland, glassy-eyed on prescription

pills to prolong her energies beyond their natural ability, opens with typical

zeal for the lyric, gyrating left to right with an exuberant Rooney as her

escort.

The couple shimmy and shake on a makeshift stage at

their high school, surrounded by Spanish-attired cohorts of the teenage sect,

before stepping onto the dance floor where they are met by a crowd of

over-enthusiastic teens, all of whom intuitively know how to samba. From here, Berkeley

weaves his spell, staging seemingly endless conga lines, interlocked, curving,

and finally, moving across one another in perfect unison with his usual mesmeric

precision. Only at the end of this ‘south of the border’ bacchanal do

Garland and Rooney emerge, sashaying from under an array of extended arms;

shoulders, bawdily gyrating as they declare, ‘Conga…boom!’ At the

outset, Garland had resisted doing this number, particularly as Berkeley’s

manner towards her could be slavish to the brink of insulting. Indeed, Berkeley

worked Garland very hard, creating even more havoc when he insisted the entire

number be shot in one continuous take to preserve its frenetic energy.

Endlessly rehearsing to ensure no mishaps, Berkeley achieved his goal. But his

efforts sent Garland to the infirmary, drained to the point of collapse by the

end of it. Viewed today, ‘La Conga’ remains one of the most spontaneous

and frenetic spectacles ever achieved in movie musicals – a real tour de force

for which Garland could count herself most fortunate to have survived its

ordeal.

Critics who had been quick to earmark Garland and

Rooney as the ‘new kids on the block’ out to make good as the screen’s

latest winning combo, were virtually ‘over the moon’ in their praise of Strike

Up The Band. Line-ups to acquire tickets for the picture’s debut at Radio

City began at 6am and were sold out weeks in advance. To promote the picture,

MGM again sent Rooney and Garland on the road, appearing live – a breakneck

schedule that cost the sensitive Garland any lasting pleasure she might have

enjoyed as the screen’s latest star. In the U.S., Strike Up The Band grossed

a whopping $2,265,000, resulting in a net profit of $1,539,000 for MGM –

another sizable smash for Arthur Freed; also, an affirmation for L.B. Mayer in

Freed’s abilities to pull off one humdinger of a movie musical with all the

spectacular aplomb Metro could afford at his disposal and in its heyday. The

showbiz bible, Variety was quick to single Garland out as having risen

through the ranks as one of ‘the screen’s great personalities…in full bloom…beyond

childhood’ and, ‘…as versatile in her acting as she is excellent in

song.’ Viewed today, Strike Up The Band has lost none of its youthful

vigor. Mickey Rooney acquits himself rather rambunctiously of the ‘Drummer

Boy’ solo. And Garland positively sparkles in the epic finale, a reprise of

the movie’s entire score, capped off by a rousing ‘marching band’ rendition

of the title tune with Rooney and Garland, locked in smile-beaming embrace,

super-imposed over a billowing Stars and Stripes. In an era where American

patriotism has taken more than its fair share of negative hits, movies like Strike

Up The Band hark back to a time when Hollywood was most definitely in the

business of promoting ma, apple pie and old glory. Indeed, MGM saw this as

their first shot across the bow at the Axis powers abroad, distinctly to

suggest that if ‘the Yanks’ were yet to be coming, then their hour of

declaration against tyranny and for the free peoples of the world, was

definitely on the foreseeable horizon.

Strike Up The Band has received a colossal treatment

on Blu-ray via the Warner Archive (WAC) in a new 4K restoration derived from

the best possible surviving elements. If this is not an original nitrate

negative, it certainly gives every indication of being one. Gray scale – check.

Contrast – double check. Fine details and a light smattering of fine grain

looking very indigenous to its source – triple check. What a joy to have Strike

Up The Band in hi-def. The movie always had an intangible beauty, but this

1080p rendering really brings out Ray June’s high key-lit cinematography to its

best effect. Age-related artifacts – gone. The movie looks as good as it ever

has, and, even better, gives an authentic feel to what audiences in 1940 must

have encountered, projected on the big screen. The audio is DTS 2.0 mono and

sounding as spiffy as ever, with a genuine clarity that belies its 80th

anniversary. Carried over from the old

DVD release, an introduction by Mickey Rooney – remastered in HD, plus, a

comedy short, ‘Wedding Bells’, and, a cartoon, ‘Romeo in

Rhythm’. We also get a stereo remix of ‘La Conga’ and two radio

promos, a Lux Radio broadcast, and, a theatrical trailer. Bottom line: with the

4th of July just around the corner, few movies are as unabashedly

sentimental about ‘America, the beautiful’ as Strike Up The Band.

This one belongs on everyone’s top shelf. You can’t classify yourself as either

a true patriot or a movie lover without this one. Oh, yeah – hear the beat of

that bonga! You bet!

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

4.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

5+

EXTRAS

3

Comments