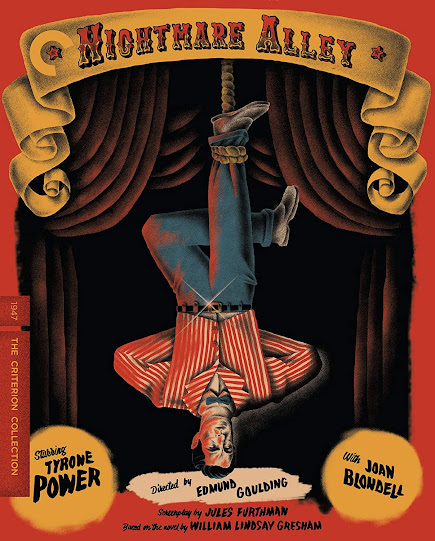

NIGHTMARE ALLEY: Blu-ray (2oth Century-Fox, 1947) Criterion

Resident 2oth Century-Fox heartthrob, Tyrone Power

made an executive – and potentially career ‘throat-slashing’ decision to star

in director, Edmund Goulding’s Nightmare Alley (1947), much to the chagrin

and strenuous objections of his boss, Darryl F. Zanuck. In the era of cinema

experimentations, where gambling men like Zanuck played fast and loose with

their profits for the sake of ‘prestige’ (pictures that don’t make money, but

inevitably elevate the stature of their industry), Nightmare Alley is

one of the irrefutable dark gems in the noir catalog, underappreciated in its

own time, and all but overlooked for Power’s brilliant performance as the unrepentantly

callous and shallow anti-hero, Stanton Carlisle. While most noir thrillers are

either detective-based or femme fatale-driven, with a firm grip on what constitutes

the general morality of the American public, the characters inhabiting Jules

Furthman's screenplay here are universally brutal and uncompromising malcontents

who live the sort of sordid lives no human being should ever even dare try.

Viewing Nightmare Alley from today’s vantage, one is immediately

awestruck by its resplendent tawdriness, the way Furthman’s art has managed to

capture the vial moodiness of its source material, skillfully to elude Hollywood’s

self-governing code of moral judgment (otherwise to have emasculated its

potency as gripping screen entertainment) and, at least in hindsight,

prophetically to foreshadow just how far our present appetite for such movies

has completely swung in the other direction. The testament to Goulding and

Furthman’s vision is likely best summed up in the negativity heaped upon Nightmare

Alley upon its general release. The New York Times chastised the film, stating

“If one can take any moral value out of Nightmare Alley it would seem

to be that a terrible retribution is the inevitable consequence for he who

would mockingly attempt to play God. Otherwise…this film traverses distasteful

dramatic ground and only rarely does it achieve any substance as

entertainment.”

Nightmare Alley is irrefutably wicked and menacing.

Teeming with the sort of diabolical heresy flying in the face of Hollywood’s

then conventional glamor and gloss, it plays much better now than it did back

then, our current disenchantment with life in general, more readily celebrated

as post-moderne art at the movies. And Nightmare Alley is

unapologetically bleak in its denouement too. There is no reconciliation for

its tarnished con artist, reduced from nightclub slickster to gin-soaked gimp,

biting the heads off live chickens in a traveling freak show. No, Nightmare

Alley is decidedly not the picture most wanted to see in 1947 and

definitely not the role matinee heartthrob, Tyrone Power’s adoring throngs of

female fans expected to find him in either.

Alas, like so many men gone off to fight, WWII had changed Power – if

not altogether physically, than sincerely, and, in increments. Power, the

dapper dude about town in so many pictures before the war, now returned to the screen,

first to appear in a white-ribbed sleeveless undershirt, then briefly in

tuxedo, before being made up as a humiliated, unshaven and drunkenly disfigured

hobo. Indeed, Power was somewhat ashamed of his pre-war efforts at Fox and

sought to expand upon his talents, also, to move away from his limited

reputation as the studio’s resident ‘pretty boy’ - the all-American successor

to the stud mantle vacated by Rudolph Valentino. It isn’t simply a physically

altered Ty Power we get in Nightmare Alley. It’s what’s going on inside

his own head that seems to haunt from the peripheries of the screen - a fellow

with something more substantial to offer from the pulpit and eager to eschew

his image as a reigning sex symbol. Alas, Ty’s star power alone was not enough

to save Nightmare Alley from becoming something of a personal incubus.

Alas, just as Zanuck had predicted, the film sank like

a stone at the box office, effectively ruining Power’s chances of ever effectively

rid himself of that formerly ensconced movie-land persona. It’s a genuine pity

too, because there is some utterly fascinating subtext to Power’s Stanton

Carlisle. He is a terrible cad, a reckless fool with women and a greedy little

bastard elsewhere, given free hand with the three who mark his time but ultimately

stain his Teflon-coated reputation as a divinely inspired mentalist, reading

people’s thoughts inside a swank Manhattan nightclub. It’s all smoke and

mirrors of course, done superficially to manipulate, cajole and entertain patrons,

but moreover to fatten Stan’s wallet, using a clever ‘code’ shown him by carny

crystal ball gazer, Zeena Krumbein (Joan Blondell), who hopes for more than

just Stan’s gratitude in return. Zeena’s married to Pete (Ian Keith), a

hopeless – if empathetic drunkard. If only she were free. But Zeena is loyal to

Pete…practically. And she is not really

Stan’s type. He prefers the inexperienced tartlet, Molly (Coleen Gray) who is

heavily guarded by carny strongman, Bruno (Mike Mazurki, doing his actor’s

specialty as the brainless hulk). Much later into this mix comes the devious

psychoanalyst, Lilith Ritter (Helen Walker), using her viper’s charm to seduce

Stan into divulging the secrets of his clairvoyant powers, then blackmailing

him with a plot to bilk a rich patron’s pockets, but keeping the kitty all for

herself.

The women in Jules Furthman’s screenplay, loosely

based on William Lindsay Gresham’s novel, are a trio of ambitious adders.

Interestingly, none ever attain the status of the traditional noir femme fatale.

This makes each of them all the more spellbinding to observe. Zeena, as

example, suffers from a queer motherly bent – or perhaps, sisterly – towards

Stan. She loves him far too deeply to ever ‘love him’ passionately. When Stan

inadvertently poisons Pete by confusing a bottle of malt liquor for a fresh

bottle of wood grain pure alcohol, even Zeena knows he didn’t mean to do it. By

contrast, Molly is practically an innocent, riding the crest of Stan’s newfound

fame as his glamorously clad assistant, feeding clues in code to questions

audience members have written down on cue cards. Stan replies with intelligent

answers that seem to have come to him through osmosis. But actually, it’s

Molly’s intonation tipping Stan off, the pair coached by Zeena on a highly

complicated code of communications. As

for Lilith, she’s devious, amoral and rotten to the core. That said, she wants

no part of Stan, other than to see him squirm. And once her tear down of his

public image is complete, she disappears, content in her utter derailment of

this man’s reputation.

Prior to Nightmare Alley, Tyrone Power had been

2oth Century-Fox’s resident and most bankable heartthrob. The heir to an acting

dynasty, in his youth Power was an uncommonly handsome leading man with boyish

charisma to boot. Zanuck was content to exploit Power’s undeniable assets in

some fairly featherweight films. But these never stretched Power’s appeal or

his abilities as an actor. For a time, Power accepted his plush treatment

without question. It had, after all, made him the envy of virtually all

Hollywood’s then reigning he-men, save MGM’s Clark Gable and freelancer, Cary

Grant - very rare company, indeed. But at war’s end, Power suddenly became

disenchanted with the prospects of returning to his alma mater for more of the

same. He was, after all, older now. And it is interesting to note the distinct

change in Power’s look in just those few short years of military service - a

harder edge with the ‘little boy’s innocence’ gone from behind the eyes, his

eyebrows particularly exaggerated. As a result, the parts Ty chose to play

after his homecoming at Fox took on more ballast, beginning with The Razor’s

Edge (1946), a costly, but lumbering monument to Somerset Maugham’s

literary examination of America’s dwindling aristocracy, in which Ty played the

introspective and philosophizing proletariat hero, Larry Darrell whose

spiritual enlightenment abroad wrecks his chances for the superficial happiness

he might have once found with a flashy lass from one of Long Island’s

‘respectable’ families.

The Razor’s Edge was lavishly appointed. But it was

not a colossal smash at the box office. Immediately following the epic

implosion of Nightmare Alley, Zanuck recalled Ty to the kinds of roles

he had made famous before the war, swashbucklers mostly, and the occasional

dim-witted screwball comedy. Alas, Ty could not assimilate back into such roles

without revealing too much of the inner adult, hardened by the European

conflict. This alone seems to have altered the chemistry of his devil-may-care

sexiness. Now, he possessed a steelier pallor.

One need only observe Power in a moment from Nightmare Alley

where Stan, reduced to a cinder of his former self and inebriated, administers

to a gathered group of train-hopping hobos, reading their fortunes by

bastardizing their memories from childhood, only to cruelly debunk the mystery

of his clairvoyance once a few of the ole rummies have already bought into his

gimmick and thereby, puncturing the balloons of their desperate need to believe

in something – anything – once again. It’s an uncharacteristically cruel and

unforgivable moment for Power’s character, still high and mighty and lauding

his ability to flimflam the ‘dumb’ masses even as he has sunk to their level

and is on the very fast track to plummeting even further within a few

additional scenes.

There is a sinister magic at work behind Powers’ eyes,

a wicked and juicy little gleam refusing to surrender. His subtle

gesticulations are expertly placed, a small shift in the arc of his slumped

shoulders, a half twist of his neck, cocked to the right as he regains a

moment’s composure to gloat about those near forgotten times when he truly was

the puppet master of seemingly anyone’s impressionable thoughts, and, most

assuredly, the unscrupulous manipulator of most women’s hearts – except, of

course, Lilith’s. Power had hoped to reinvent his screen presence with Nightmare

Alley; to deepen the breadth and scope of his actor’s craft as, perhaps, he

had seen Dick Powell do over at Warner Bros. from crooning contract ingénue,

warbling sweet nothings into Ruby Keeler’s eardrum, now effortlessly morphed

into the grittier gumshoe, Philip Marlowe in Murder My Sweet (1944).

Unfortunately for Power and Zanuck – who had begrudgingly agreed to invest in Nightmare

Alley, perhaps assuming Ty’s star power alone would be enough to salvage the

picture – audiences did not want to see their hero stray so far from his patented

persona.

Zanuck was taking no chances with the reputation of

his biggest box office draw. The opening scenes in Nightmare Alley give

us Tyrone Power – star and stud, immaculately quaffed, his taut body poured

into tight fitting tanks tops or impeccably tailored penguin suits - the

peacock, momentarily given back his strut on loan. There is a deliciousness to

Ty’s re-entry into the movies, Power seemingly going along with the look of a

star – if not its Teflon-coated charisma. In fact, almost from the moment he

appears on camera, there is something remiss about his Stanton Carlisle. He is

too self-assured, too vain and much too fascinated with his own abilities. He

lacks the one essential necessary to be considered any woman’s dreamboat - an

understanding heart. Without this, Power’s handsome carny is little more than

the proverbial beast wrapped inside beauty’s shell. The Furthman screenplay gives Power a

singular moment in which to express his mild – and fleeting – repentance,

immediately following his discovery he has accidentally switched Pete’s

libation from malt liquor to blood-poisoning pure alcohol. Arguably, it is an

essential grace so the audience will not end up hating his character outright.

But it offers very little tangible proof Stanton Carlisle is not a corrupted

and contemptable human being.

The screenplay does, in fact, take pity on Power’s

fall from grace in the eleventh hour, Stan collapsing in Molly’s arms after she

has discovered him reduced to the status of a kept mutant in a travelling

sideshow, shouting uncontrollable and disturbing animal grunts while hunted

down by his angry handlers. It’s Power morphing from man into beast, or perhaps

merely revealing his character’s truest self to the world – the shyster now a

primal gimp, as it were – forcibly stripped of his congenial façade and

prematurely aged, that is startling – even heartrending – to observe. Here is

an actor unafraid to bare all for the sake of his art, to dismantle our

preconceived notions about his own camera presence and explore the depth and

purpose he possesses as a legitimate actor, and, to boldly plumb uncharted

territories of human suffrage, distilled to their most prehistoric rape of the

soul, letting the audience in on the ugly side of such self-destructiveness and

arctic desolation.

William Lindsay Gresham’s novel, first published in

1946, has long since been hailed as a truly unsettling, raw and uninhibited

magnum opus. Owing to concessions made for the sake of satisfying Hollywood

censorship, Goulding’s film is arguably no less potent, creepy and utterly

jaundiced in its portrait of these seedy denizens, scampering like rats over

one another in their jaded inner darkness and despair. Zanuck had had his

misgivings about making the movie. But he had faith in his star, who passionately

championed to play the lead. Artistically speaking, that faith was not

diminished. Power is magnetic in the role. To add another layer of verisimilitude

to the film, art directors J. Russell Spencer and Lyle Wheeler were given carte

blanche to build a full-scale carnival on ten acres of the Fox studio back lot,

populating their artifice with nearly one hundred genuine sideshow attractions.

The unsung hero of Nightmare Alley is undeniably cinematographer, Lee

Garmes, a craftsman par excellence, taking the precepts of chiaroscuro lighting

to their extreme. In one scene, Garmes’ shadows are so harsh and pronounced

they virtually obscure half of Joan Blondell and Tyrone Power’s heads in a

medium two shot that lingers for several minutes on the screen, a very gutsy

move in the days when audiences paid to ‘see’ their stars.

Nightmare Alley begins at the carnival, a place

for escapist fun and superficial amusements – at least for its patrons. But

behind the scenes there lingers a den of iniquity, constantly threatened by

internal power struggles, jealousy and, of course, deception. We meet Stanton

Carlisle (Power), a bored-with-life rigger and part of tarot card reader,

Mademoiselle Zeena’s (Joan Blondell) entourage. Stan helps pull the wool over

the patrons’ eyes. Zeena has, in fact, fallen on some very hard times. Once a

top-billed act with her husband, Pete (Ian Keith), she has committed to a solo,

ever since Pete fell into a bottle and has been quietly unable to escape his

torturous alcoholism. It’s wrecked the act, their marriage and, at least

superficially, their love for each other. Alas, Zeena is empathetic to her

husband’s plight, the screenplay implying the crux of Pete’s spiral into

oblivion was a past indiscretion committed by Zeena.

Eventually, Stan discovers Zeena is holding out on

selling the code to prospective buyers. He attempts to schmooze his way into a

quick steal. But Zeena is hardly a novice. She also doesn’t buy Stan’s amorous

act for a second, although she does harbor hidden sexual desires about him as

well. Zeena, however, is focused on raising enough money to send Pete to a

detox clinic. Stan is an enabler, smuggling moonshine to keep Pete

appropriately inebriated and out of the way. The plan backfires when Stan,

returning in the pale moonlight to Pete and Zeena’s tent, accidentally mistakes

a bottle of wood grain alcohol for moonshine. Pete drinks it and dies. Keeping

the particulars of this mix-up to himself Stan, ever the opportunist, now

presents himself as Zeena’s last hope to keep her act alive. There is no other

way. She must teach him the code so he can become her faithful assistant. Reluctantly,

Zeena complies, unaware Stan has already begun to gravitate his affections toward

the much younger/less jaded, Molly. When the pair’s illicit romance is found

out, Bruno forces Stan into a shotgun wedding.

Stan elects to leave the carnival, taking Molly with

him. In a very short period, Stan teaches Molly Zeena’s code and the two embark

upon a whirlwind career in Chicago as ‘The Great Stanton’ and his

assistant. Sitting in the audience is Lilith Ritter, who becomes insidiously

fascinated by the act - actually, more by Stan, whom she lures away from Molly.

Suspecting as much, Molly is opposed to Lilith’s plan. She hasn’t been fooled

into thinking Stan possesses a natural clairvoyance. So, she makes Stan an

offer. As a prominent psychoanalyst, Lilith will provide Stan with easy access

to her own patient’s confidential case files, thus plying her most desperate

clientele with the even more treacherous ruse Stan can communicate with their

dearly departed loved ones. The plan is

practically foolproof and will net the pair untold riches from those rich in

purse though utterly naïve and ready to believe anything is possible.

Stan’s greed knows no boundaries. He and Lilith latch

on to extreme skeptic, Ezra Grindle (Taylor Holmes), who has lost the great love

of his life and is anxious to be reunited with her even for the briefest of moments.

Noticing an uncanny resemblance between Grindle’s dead paramour and his own,

Stan cajoles a very reluctant Molly to pose as the living corpse. However, Molly’s

love for Stan is tested when Grindle, falling complete for their charade -

hook, line and sinker - suffers a tearful breakdown in her presence. Molly

reneges on the plan, confessing all to Grindle who vows to hunt down Stan and

Lilith and see to it both are prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.

Desperate to avoid incarceration, Stan hurries to make off with the loot

embezzled from Grindle’s account, only to discover he too has been taken.

Lilith has left him a measly $150 of the promised $150,000. Worse, Lilith has

concocted a foolproof alibi to stave off her own imprisonment. She will testify

under oath Stan was a patient of hers, mentally disturbed and suffering from

delusions of grandeur. It was his plan to swindle Grindle – not hers – and his

responsibility to face the consequences of these actions now.

Cornered and facing prosecution, Stan is forced to

flee. He gives Molly the $150 dollars and urges her to disappear back to the

carny where their empathetic friends will surely care for her out of pity. Stan then disappears, using a series of

disguises, becoming a recluse first, then a drunk and eventually riding the

rails with no plan of action for the future. At the end of his proverbial rope,

Stan attempts to land a job at another carnival as a clairvoyant fortune

teller. The proprietor is unimpressed. Moreover, he already has such an act in

his employ. But he could always use a gimp - a sideshow oddity who will shock

and revile the audience by eating live chickens. Realizing he has sunk to an all-time

low, Stan agrees to play this part. But it preys upon his mind. He loses his

grip on reality, actually becoming a freak show geek. Mercifully, Molly

discovers Stan working for the same carnival. Collapsing in her arms, Stan

repeats a scene that occurred earlier between Zeena and Pete, Molly vowing to

nurture and nurse Stan back to health and his former self.

Nightmare Alley is about as unsettling and dire as

noir melodramas get. Author, William Lindsay Gresham had written the novel –

his first – while serving in the Loyalist forces during the Spanish Civil War,

befriending a former carny who presumably relayed such tales to him in their

spare time spent together. The book was a big hit, Gresham using a different

Tarot card to introduce each chapter. The film ditches this motif for a more

straight-forward approach to the narrative. In retrospect, there is a mild,

though palpable and lingering anxiety and hesitation on Goulding’s part to

evoke the more hellacious particulars of the novel, especially those in the last

chapters dedicated to Stan’s severe downward spiral. Perhaps, Zanuck too was

pulling more than a few strings to insist, at least, in part, Tyrone Power

appear as any star of his caliber should - virile and immaculately

dressed. True to the Production Code,

the grotesque act of devouring live fowl is, of course, something we never see.

But it is implied with ominous sound effects and a persistent

half-human/half-animal growl heard at both the start and near the end of the

picture, allowing our collective imaginations to run wild. And Power does the

almost unthinkable. He has makeup artist, Ben Nye fix him with a prosthetic

nose and eye pieces that completely distort the near perfect symmetry of his

facial features.

Ably abetted by Lee Garmes' cinematography - a

glowering chiaroscuro fantasia that bathes its cast in unrelenting darkness (the

actors frequently emerging from the inkiest of shadows, especially Power –

debuted as the anti-Power - or at least, a Power unlike any we have come to

admire and appreciate before or since), Nightmare Alley persistently

devours us with its shocking amount of sexually-charged gutter depravity,

virtually unseen – and certainly, untested - in American movies before its

time. Given the public’s penchant for wanting stars to look like stars, their

level of expectation force-fed on a daily diet of frothy entertainments, even

ambiguous film noirs that, nevertheless, usually had the side of the moral

right triumphant before the final fade out, is it any wonder Nightmare Alley

failed at the box office? Possibly the fault belongs to Power - not because he

isn't spot on in the role, but rather because he is, and it is not the Tyrone

Power his fans have paid to see. Whatever the reason, Nightmare Alley is

far from an artistic failure. In fact, it has since acquired a solid reputation

as one of the best – if most sinister – film noirs in cinema history.

Well, it’s about ‘friggin’ time! Nightmare Alley

makes its American debut on Blu via Criterion. Precisely why it has taken this

long to get a ‘region A’ release of this fantastic film remains open for

discussion. And, while cited as a ‘New 4K digital restoration’ image quality

here still suffers from an inherent smooth quality sans film grain, while

marginally improving on fine details and textures, and, with a distinctly noted

‘brightening’ of the overall contrast. Is this how, Nightmare Alley

looked theatrically? Like all of Fox’s back catalog, to have suffered the

indignation of having original elements junked in the mid-1970’s merely to

clear out vault space, I will assume here that the restoration efforts are

working from less than ample source material, and certainly not from properly

archived nitrate elements. So, I suppose this is as good as it’s ever going to

get for this deep catalog title. We get

a PCM mono track – very flat but nevertheless audible. From 2005, an audio

commentary featuring historians, James Ursini and Alain Silver. A new 30-min.

interview with critic, Imogen Sara Smith, a 12-minute interview with Coleen

Gray from 2007, and another new-to-Blu 20-minutes with sideshow historian, Todd

Robbins make up the bulk of the extras. We get a disposasble 10-minute audio only

excerpt from Henry King recorded in 1971, a trailer and Criterion’s usual

attention to liner notes, this time supplied by screenwriter, Kim Morgan. Bottom

line: Nightmare Alley is highly recommended. Turn out the lights, dear

children. It’s time for a very good scare!

FILM RATING (out of 5 - 5 being the best)

5

VIDEO/AUDIO

3.5

EXTRAS

5+

Comments