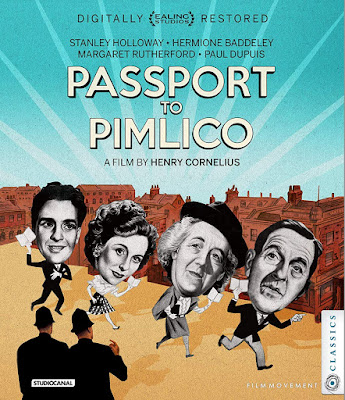

PASSPORT TO PIMLICO: Blu-ray (Ealing Studios, 1949) Film Movement

An irreverent send-up to that stuffy ‘can do’ Brit-based spirit

that served the nation so defiantly - if eloquently – during WWII, director, Henry

Cornelius’ Passport to Pimlico (1949) resists the urge to veer full throttle

into ribald English farce, and instead, invests itself superbly in the comings

and goings of a small collective, determined to establish and maintain their independence

from a socialist regime. Ironically, in this instance, the stance is taken by

the people against their own government, as Pimlico’s residents discover buried

French treasure beneath their streets, suggesting the area was once governed by

Burgundian authority. However, declaring themselves a sovereign principality in

the heart of London does not go over so well with Whitehall. And thus, the

tug-o-war to regain control over these few square blocks of choice London real

estate begins; the British government’s imperiousness repeatedly challenged

with brilliantly staged roadblocks by the inhabitants of this, as yet ration-suffering/bombed

out enclave of Londoners, yearning to breathe free. T.E.B. Clarke’s screenplay subtly accentuates,

and reenacts the parallels between the current situation affecting Pimlico’s sovereignty

and the plight of the British people during WWII: the newly established Burgundians,

absolutely refusing to surrender their newfound unity and ‘black market’

extravagances to drab, cash-strapped post-war London. Passport to Pimlico

clearly suggests that the well-being of this tiny enclave of individualists may

not go hand-in-glove with the established order operating outside its

cloistered community.

As such, the picture remains a gently rebellious reverie. Yet, it

celebrates those quintessential British peculiarities, at once devout to eccentricity,

forbearance and conciliation, along the way, accentuating that ‘stiff upper-lipped’

insular distinctiveness and civility. Produced by Ealing Studio’s mastermind,

Michael Balcon, Passport to Pimlico was one of three comedies shot

consecutively on the backlot, alongside Whisky Galore! and Kind

Hearts and Coronets – a triumvirate of classic farces, to endear audiences

to Ealing’s newborn stature as a studio devoted to ribald English wit. Clarke’s

screenplay takes its inspiration from an incident during the war: the maternity

ward at Ottawa Civic Hospital temporarily declared extraterritorial by the

Canadian government, allowing Netherlands’ Princess Juliana to give birth to

Princess Margriet, technically born on Dutch territory, so as not to lose her

right to the throne. Clarke was also inspired to recreate the food and supply

airlift missions during the 1948/49 Berlin Blockade, re-envisioned here as drops

of food supplies into the Burgundian enclave. In its early gestation, two cast changes

sealed the immortality of the picture: Arthur Pemberton, ostensibly ‘the lead’

in this ensemble, to have been played by Jack Warner, instead given over to the

effervescent Stanley Holloway, and Margaret Rutherford, cast as the easily stirred

Prof. Hatton-Jones, after beloved star, Alastair Sim turned it down. Rutherford’s

was the unlikeliest of stars. For although she had made the rounds in British

theater and picture-making since 1936, it was not until her turn as the dotty psychic

in David Lean’s Blithe Spirit (1945) that Rutherford’s career really

took off. Blessed with a supremely weather-beaten, bug-eyed and lopsided visage,

lumpy/dumpy body, and, perpetually befuddled good nature to see the world more

clearly askew, Rutherford’s iconoclastic humor endeared her to audiences

everywhere; herein, as the Medieval expert who revels in Pimlico’s historical

reawakening.

While the machinations of these liberated residents seemed effortless on

the screen, making Passport to Pimlico proved anything but a pleasant

exercise. For one thing, although set during the record-breaking heatwave of

1947, the picture was actually shot in 1948 – the wettest summer on record, causing

numerous setbacks in the production schedule and causing the budget to balloon from

delays brought about by the chronic rain. Shooting began at the crack of dawn

in an attempt to get at least one or two scenes in the can by 9 am.; on

average, barely 2 ½ minutes of usable footage lensed per day. For another, the

working relationship between director, Cornelius - hand-picked by Balcon – and the

producer/head of the studio did not mesh. In fact, Balcon grew increasingly discontented

with what he perceived as Cornelius’ poor direction. As a result of their

constant friction, Cornelius left Ealing after Passport to Pimlico had

its exuberant premiere, never again to work at the studio. As shooting in

Pimlico proved quite impossible, Lambeth stood in for exteriors, a full-scale

set of the bombsite built at the junction between Lambeth and Hercules Road.

And although ‘improvements’ were made to the area in order to shoot the movie,

virtually all of them had to be reversed at the end of production, restoring

the area to its post-war state of bomb-damage in order for its residents to

claim war-time compensation.

Passport to Pimlico opens with a ‘dedication’, in memory of wartime

rationing. We debut in a post-war London, an area where an un-exploded bomb

remains corded off just below street level. The local council has decided that

instead of diffusing the device, it will be more cheaply detonated in just a

few days, giving locals ample opportunity to secure their homes and shops.

Alas, a few wayward urchins, playing with a large drum, deliberately set off

the explosion ahead of time. Although no one is injured, the event is not

without incident. In approaching the site for inspection, local shop keeper,

Arthur Pemberton slips and falls down the significant indentation, only to discover

an undetected catacomb containing rare artwork, coins, jewelry and an ancient

manuscript. The document is authenticated by historian, Professor Hatton-Jones

as the royal charter of Edward IV who ceded his house and its estates to

Charles VII, the last Duke of Burgundy, presumed dead at the 1477 Battle of

Nancy. As the charter was never revoked, Pimlico is still legally part of

Burgundy. Since the British government has no legal jurisdiction, it requires

the locals to form their own representative committee, according to the laws of

the long-defunct dukedom before any negotiations to reclaim the territory can ensue.

Ancient Burgundian law requires the real Duke of Burgundy appoint the acting

council. Enter Sébastien de Charolais (the elegant, Montreal-born, Paul Dupuis)

as the current Duke, authenticated by Hatton-Jones. Swiftly, Sebastien forms a

governing body to include local policeman, Benny Spiller (Roy Carr), and bank

manager, Mr. Wix (Raymond Huntley). Meanwhile, Pemberton is appointed as

Burgundy's Prime Minister. The newly amalgamated council begins discussions

with the British government, keenly concerned over the dominion of the newly

unearthed Burgundian treasure.

As the new Burgundians realize they are no longer subject to post-war

rationing or other restrictions, the district quickly degenerates into an

on-going party-like atmosphere, infiltrated by black marketeers and shoppers

eager to capitalize on these ill-gotten gains. Quite unable to manage the

situation, Spiller appeals to the British government. In reply, the British

authorities cord off the Burgundian territory with barbed wire. They further institute

an inspection check-point, demanding passports from the residents to cross from

‘one nation’ into the next, and creating a bottleneck for those attempting to

cross the picket, merely to shop for black market goods. Retaliating against

this heavy-handed bureaucracy, the Burgundians prevent the London Underground from

passing through without demanding their own passport inspection and taxation.

Whitehall hits back by breaking off all negotiations, leaving Pimlico isolated.

Now, the residents are encouraged to ‘emigrate’ to England. In a show of their stalwart

solidarity, few choose to leave their homes. Power, water and food services are

all cut off. In reply, the Burgundians surreptitiously attach a hose to a

nearby British water main, filling the bomb crater to capacity. Alas, it also

floods the food store. With no sustainable rations left, the Burgundians

prepare to surrender. Instead, sympathetic Londoners toss food parcels over the

barrier. Flush with supplies, the Burgundians are further assisted in their

plight for independence by a helicopter pumping fresh milk through a hose, and

pigs being parachuted into the area. Chagrined in their fight for supremacy,

the British government comes under public pressure to resolve the problem,

their current plan to starve out the populace, not only proving quite difficult,

but very unpopular. Wix, now the Burgundian Chancellor of the Exchequer

suggests a loan of their newfound treasure to Britain. This deadlock

eliminated, the embargo is lifted and Burgundy willingly rejoins Britain. As if

by kismet, the return to post-war rationing intrudes upon the Burgundians

celebratory outdoor banquet, immediately stricken by a torrential downpour.

Despite its irreverence towards authority, or perhaps, because of it, Passport

to Pimlico was a smash hit for Ealing. Critics warmly embraced the picture,

as did audiences; The Observer’s C. A. Lejeune, commenting that “the

end comes too soon, which is something that can be said of very few films.”

In hindsight, Passport to Pimlico is representative of Ealing’s superb

stock company of players – a reoccurring roster of solid performers, given ample

opportunity to show off their assets.

Standouts include the aforementioned Stanley Holloway and Margaret Rutherford;

also, the marvelous Hermione Baddeley as tart-mouthed cockney dress shop proprietress,

Edie Randall, and, Barbara Murray, cast in what might otherwise have easily become

the disposable part of the romantic ‘interest’ – Arthur’s daughter, Shirley

Pemberton. Because Ealing employed virtually all of these talents in an

on-going basis, their presence as a close-knit community herein is not only

wholly believable, but very much the lynch pin that holds the occasionally

meandering screenplay together. Even when the dialogue becomes intermittently

bland, or the situations diverge from the main plot, these noted thespians

provide something interesting to consider; their presence, both sincere and fêted

by the lingering of their memories in our hearts. Passport to Pimlico

was nominated by the British Academy for Best Picture, but lost – forgivably –

to Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949). It also received a nod for Best Story

and Screenplay – the award instead, going to Battleground (1949). Viewed

today, Passport to Pimlico is a deliciously devious minor programmer of

the ‘little gem’ class in picture-making, soon to be made extinct by the

post-war verve for bigger movies. While it is not as easily recalled from memory

today, it nevertheless remains indelibly etched into our collective

consciousness, and is utterly charming to boot.

Passport to Pimlico arrives on Blu-ray via Film Movement’s acquisition of

StudioCanal’s ‘newly restored’ 2K elements. The results are a mixed bag. Owing to

decades of improper archiving, and not nearly as much consideration given to

these dupe elements as other StudioCanal releases, Passport to Pimlico

looks a little worse for the wear. The B&W 1080p transfer sports a lot of light

breathing around the edges, blown-out contrast, a lack of film grain, but

oddly, an amplification of digitized grit, and, a ton of streaking and modeling.

Age-related artifacts have been cleaned up – no dot crawl, tears or white speckling.

But honestly, the results herein are decidedly a letdown. The image is frequently soft, with a loss of

overall find detail, except in close-up. There are no true blacks – only tonal

variations of grey. Perhaps worst of

all, the DTS 1.0 mono audio is strident and grating on the ears. Most of the

time, the audio just sounds thin and shrill. This release is also very scant on

extras. We get a brief bit of introspection from BFI curator, Mark Duguid about

the locations used in the picture. There is also a ‘restoration comparison’ that,

frankly, does not show all that much improvement between the ‘before’ and ‘after’. Bottom line: Passport to Pimlico’s

transfer is not up to snuff, belying it being advertised as ‘digitally restored’.

Extras have been added as a forgettable afterthought and do not augment our

viewing experience. Judge and buy accordingly.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

3.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

2.5

EXTRAS

1

Comments