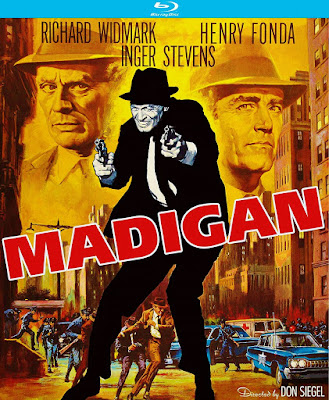

MADIGAN: Blu-ray (Universal, 1968) Kino Lorber

Good roles for aging, but still great stars were exceedingly hard to

come by in 1968; the last gasps of the old-time Hollywood establishment still

refusing to entirely depart their once seemingly indestructible kingdoms; the

new order, buffeted by a creative unrest to do things ‘differently’ than their predecessors,

and, the thorough implosion of the industry’s self-governing code of ethics,

leading to pictures with less plot, more action, and increasingly, more

tasteless – if strangely appealing – situations. Glamour was therefore

decidedly passé, and unlikely to return as the byproduct du jour. Interestingly,

the noir crime thriller, all but wiped out after 1949 by the plush and padded gigantism

of mid-fifties picture-making, and its post-fifties fallout, weighed down in fewer-made

but even more elephantine ‘road show’ spectacles of varying genres, effectively

marked its reemergence mid-decade with 1966’s Harper, 1967’s Point

Blank, and, 1968’s The Detective, to star – respectively – Paul Newman,

Lee Marvin and Frank Sinatra; arguably, three of the biggest names in showbiz,

with one major note of distinction. The classic crime pictures, collectively lumped

under the banner as ‘film noir’ – a movement, not a genre – were usually

cheaply made, B-budgeted B&W thrillers with few A-listers to partake of the

exercise. Comparatively, the neo-noirs from the mid-sixties were given

considerable cash and talent to float them to profitability at the box office. And

the fashionable streak showed no signs of diminishing with director, Don Siegel’s

Madigan (1968) – a gritty drama tricked out in the trappings of a conventional

crime caper but set in the bowels of New York’s decidedly low-rent district. Madigan stars Richard Widmark, whose

screen persona had miraculously morphed from playing squinty-eyed psychopaths (Kiss

of Death, 1947) and repugnant racists (No Way Out, 1950) into a

fallow period of adjustment, and then, even more miraculously, a resurgence on

the other side of the proverbial fence, as forthright and honorable figures of fixed

integrity in pictures like The Alamo (1960), Judgment at Nuremberg

(1961), and, How the West Was Won (1962).

Madigan straddles a chasm in Widmark’s bipolar capacities as

an actors’ actor. For although Dan Madigan is a New York detective out to rid this

decaying metropolis of yet another heinous killer, he possesses a streak of

vengeance that leans toward the vigilante, soon to become the purveying ‘norm’

of seventies’ anti-heroes in movies like Klute and Shaft (both

made and released in 1971). It must be noted that Madigan was conceived

under duress; an all-pervading friction between producer, Frank Rosenberg (who

considered himself ‘the boss’) and Siegel, who rightly surmised that once the

cameras were rolling, only his opinion mattered. Whether from spite or just

plain lack of logic, Rosenberg scheduled the first day’s shoot to include

photographing of the last scene in the movie, depicting an embittered Julia

Madigan (Inger Stevens) reigning down her contempt for Commissioner Anthony X.

Russell (Henry Fonda) over the death of her husband. To complicate the shoot,

Stevens was also required to report earlier in the same day for wardrobe tests,

leading to a conflict that stressed the actress to the point to distraction.

Reportedly, Siegel told Stevens to channel her abject frustration and contempt

for Rosenberg into the scene yet to be played, adding later, “Miss Stevens

gave a startling portrayal, truly magnificent and brave.” Producer and

director also came to loggerheads over a scene where Russell enters a room,

encountering the half-naked Tricia Bentley (Susan Clark) lying in bed, uttering,

“You can open the other eye now. I made coffee.” Rosenberg demanded this

scene be reshot as Fonda had forgotten to add the word ‘the’ in front of

‘coffee’. When Siegel refused, Rosenberg ordered the line redubbed in post-production

to include ‘the’ word. But the most significant conflict arose over

Siegel’s decision to overrule Rosenberg’s choice of location for the climactic ‘chase’

sequence.

While most of Madigan was photographed in New York, plans for the

finale were relocated to Los Angeles after a car carrying Widmark and co-star

Harry

Guardino (Det. Rocco Bonaro) was brutally attacked by gangs in Harlem. After a

property man was violently mugged, Madigan prepared to shoot its climax

in L.A. – alas, on a location hand-picked by Rosenberg that Siegel thought

utterly un-New York like. Having found an alternative more suitable, but rejected

by Rosenberg, Siegel went over his producer’s head to Universal Studio chief,

Lew Wasserman who concurred with Siegel’s choice and green-lit the change; a

very bitter pill for Rosenberg to swallow.

And Siegel was, by no means, the only person to have his difficulties

with Rosenberg. Henry Fonda would later suggest the producer had distilled his

initial interest in the project by making wholesale changes to his character

that truly watered down his impact. “He just wouldn't listen to anything,” Fonda

later recalled, “He fancied himself a writer and rewrote scenes which we'd

try to change on the set, but eventually he'd make us dub it the way he had

written it, putting single words back in.” In the end, it was Siegel’s temerity

that impressed everyone the most, and made for a salvageable work environment. “He

could have slid over the ending we wanted,” Widmark reasoned, “…but no sir.

He fought like a bastard…and he has taste.” Widmark would later suggest Siegel

was one of only three directors he considered ‘worth’ working for – the other

two being, John Ford and Elia Kazan.

Based on Richard Soughherty’s ‘The Commissioner’, and shot almost

entirely in Manhattan’s Spanish Harlem, Madigan is a skillfully

assembled actioner with a real slam-bang and thoroughly unanticipated finale –

the death of its central character. In hindsight, the picture’s moral ambiguity

points to the more complex and ‘incomplete’ crime/drama offerings yet to follow

it - Dirty Harry (and its sequels) and The French Connection (both

made and released 1971). Madigan’s screenplay, co-authored by Howard

Rodman (who opted for the nom de plume, Henri Simoun, because he disliked the

movie so much) and black-listed writer, Abraham Polonsky, is a potpourri of

time-honored edicts about God’s lonely man; the seemingly tarnished ‘white

knight’ to have been knocked from his charger, bloodied but unbowed, and

mercilessly refusing to give in, whatever the consequences. The picture exists

largely in a den of moral turpitude in which only the villains are clearly

delineated as ‘bad’; the rest, settled into the mid-range mire of an

interminable purgatory by their own design. Madigan’s Achilles Heel, as

example, is that he will not give up the ‘good fight’, but especially when

goodness has absolutely nothing to do with it! He and Det. Rocco Bonaro are

sent to apprehend Barney Benesch (Steve Uinhat), a thug hiding out in a rundown

flat. Too bad Benesch is in bed with a naked woman when the cops break down the

door. Distracted by a pretty face (other appendages optional), Madigan and

Bonaro allow Benesch his escape.

Understandably, this does not sit well with Police Commissioner Anthony

X. Russell who chastises his men, then puts them on 72-hours’ notice to hunt

down Benesch and deliver him to justice. Madigan and Bonaro could respect a man

like Russell, if only Russell had enough respect for himself. Alas, he has

become romantically inveigled with the voluminous Tricia Bentley. Russell’s colleague,

Chief Inspector Charles Kane (James Whitemore) is also not above taking bribes

to keep various brothels open. And Russell is also forced to contend with the

formidable, Dr. Taylor (Raymond St. Jacques), a black minister whose activist

son has been ruthlessly assaulted by racist cops. On the home front, Madigan is

under constant pressure from his socialite significant other, Julia who chronically

prods him to seek employment in a profession that is not only safer but better suited

with her ideas of their social caste. Despite his looming deadline, Madigan tries

to assuage Julia’s socio-sexual frustrations by spending more time with her.

Unbeknownst to Julia, however, Madigan has already taken up with rumpled

nightclub chanteuse, Jonesy (Sheree North) who knows he only has eyes for

Julia, but continues to allow herself to be used as his ‘friendly port’ whenever

their home life becomes too intense – requiring a momentary separation.

Confronted by Russell with evidence of his bribery, Kane confides he was

trying to help his own son out of a jam. Kane offers his resignation, but

bitterly resents Russell's moral outrage. After all, what would the Commissioner

know about fatherhood? In another part of the city, Madigan escorts Julia to a gala

for the department at the Sherry-Netherland Hotel. Alas, Julia’s hopes for a

memorable evening together are dashed when Madigan announces his plans to leave

her at the soiree while he skulks off to work on his case. Keeping Julia happy

falls to Captain Ben Williams (Warren Stevens), who rather insidiously preys on

her insecurities to get her tipsy, and then, attempt a seduction. At the last

possible moment, Julia resists and withdraws. It’s no use. Whatever he is,

Julia loves Madigan. Meanwhile, the elusive Benesch resurfaces, killing two

cops with Madigan’s gun. Infuriated, Madigan and Bonaro get a badly needed

tip-off from bookie, Midget Castiglione (Michael Dunn), who implores them to look

up the pimp, Hughie (Don Stroud). Tracing Benesch to a seedy apartment, Madigan

and Bonaro set up a police cordon and call for his surrender. Refusing, Benesch

holds his position while Madigan and Bonaro rush the building. Alas, time has

run out for Madigan. In his exchange of gunfire, he is fatally shot before

Bonaro manages to kill Benesch. Accusing Russell of being a heartless administrator,

Julia storms out of his office a dejected train wreck. Reassessing her

indictment of him, Russell is joined by Inspector Kane – neither having quit or

been fired. Kane now inquiries about Dr. Taylor’s situation and other pending

cases. To all his queries, Russell merely shrugs, suggesting the loose ends

will be addressed in some distant concept of a ‘tomorrow’ likely never to come.

Very much employing Madigan as his own statement piece to correlate

the similarities between an ineffectual and marginally corrupt law enforcement with

the escalation in violent crimes afflicting New York City circa 1968, director,

Don Siegel has, in hindsight, created one of the stellar time capsules from this

decidedly unflattering period in the Big Apple’s metropolitan tapestry. Madigan

– the movie - lays bare a cesspool of social depravity, overtaken the

post-fifties optimism/post-sixties ‘flower-power’ love-ins for humanity at large.

There is no love lost between the characters who populate Siegel’s hard-hitting

and edgy actioner and Siegel’s sentiment for a society at large, having veered

wildly out of control, but on its own terms, to have entirely fallen off its

moral axis. Indeed, it is difficult to interpret whether art is imitating life

here or the other way around. Richard Widmark’s approach to Dan Madigan is

tinged with a glint of personal regret. It makes for a fascinating character

study. But mostly, he plays the unrepentant policeman as an avenging junk yard

dog, too woefully invested in the particulars of his single-minded revenge to

truly give a damn about his own life. It is an uncompromising portrait to be

sure, and one for which Widmark – an actor of many faces and acting styles –

seems so perfectly born to have played. Despite changing times and tastes, Madigan

remains a step ahead of the average crime/thriller/drama – the polarizing

and popularized main staple in Hollywood for a time. Exposing urban blight and

decay as the concrete manifestations of each character’s self-imploding lack of

judgment, the picture startles us with its powerful imagery, lensed to perfection

by Russell Metty’s extraordinary camerawork.

Madigan was a huge hit for Universal; so much, that in 1972,

the studio elected to literally resurrect the character as a reoccurring part

of NBC’s Wednesday Mystery Movie franchise. Widmark returned. But television’s

budget restrictions and rather mediocre writing ensured Madigan was

again, not long for this world. After only a single season, of which Madigan

filled a meager six episodes, the character and franchise quickly and quietly

vanished from view, seemingly to be forgotten. Viewed today, Madigan –

the movie is a great piece of cinema, thanks to Don Siegel’s unrelenting and

purposeful pursuit of perfection. And now, after far too long an absence, Madigan

comes the Blu-ray, via Kino Lorber’s alliance with Universal. Before getting

excited, let us preface this review by suggesting again, it’s Universal – a studio

unapologetic about dumping their past on home video with little to zero upgrading

done on original elements before slapping them to disc. Kino is at the mercy of

Uni. So, to find most of Madigan looking adequate to just a hair above

base-line acceptable is, frankly, a pleasant surprise. In 1080p, the Panavision

image looks quite film-like with good solid colors, better than anticipated

contrast, and a light smattering of grain, indigenous to its source. There are

one or two instances of light speckling, but otherwise, the image is impressively

free of age-related artifacts. The 2.0 DTS mono shows off Don Costa’s

underscore with clean dialogue to boot. We will give a shout out to Kino, for

splurging on a new audio commentary from historians, Howard S. Berger, Steve

Mitchell and Nathaniel Thompson. This triumvirate of well-informed fellows

really get into the nitty-gritty of things. We also get a theatrical trailer

and TV spots. Bottom line: Madigan is

a solid actioner with a lot of guts. While it has dated – considerably –

Siegel’s finesse and Widmark’s central performance keep the picture fresh.

While not entirely a quality affair, Uni shows mid-grade competence here. The

Blu-ray looks solid enough, if hardly perfect. Recommended.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

3.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

3.5

EXTRAS

2

Comments