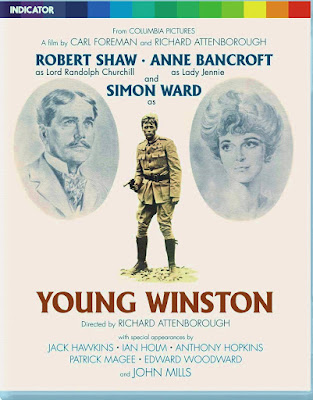

YOUNG WINSTON: Blu-ray (Columbia, 1972) Indicator/Powerhouse

I am extremely fond of Sir Winston Churchill’s off-the-cuff reply to a glib

reporter who, upon inquiring how Churchill believed history would come to judge

his legacy, with a wry glint of confidence, replied, “Oh, favorably…for I

intend to write it!” And indeed, men of Churchill’s caliber, even in his

own time, were extremely hard to come by.

There is only one Winston. Whether one chooses to regard him as titan, tyrant,

master-planner, or bungler with all the right missteps fit neatly into the

messy tapestry of the mid-20th European conflict, Churchill’s legacy

remains that of a great man, a true statesman, a superb leader, and a fallible

figure, who may have occasionally mislaid the particulars, but instinctively could envision the grander purpose meant to be achieved, regardless of the

immediate consequences – even, on occasion, to his allies. I hesitate to begin any sentence with ‘men

like Churchill’, because there has never been, nor will there ever be,

another quite like him; pugnacious, exacting, caustic and calculating. His

generation have all but evaporated from our present political landscape. From

our current grotesquely skewed perceptions of valor, Churchill’s authorship –

prolific to say the least – has been reinterpreted as chest-puffing self-pontification. Pragmatically, however, Churchill had a great

deal about himself to champion, discuss and deconstruct. Nor did he shy away

from suggesting that ‘his interpretation’ of events was simply that, and would,

undoubtedly, with the passage of time, come to be put under the microscope of

impossible scrutiny. For here, in one mesmerizing lifetime, was a man who could

lay claim to having straddled the chasm, even largely reconciled the seemingly

irreconcilable variances between his social caste – born to affluence – and a passionate

nationalism that caused him to pursue careers as a politico, army officer and

author; an intellectual, unafraid to inveigle himself in the grittiest of

struggles, diving headstrong into the quagmire of several wars, but moreover, stamping

his personal imprint on the times in which he toiled, arguably, to affect a ‘mostly’

positive outcome.

Churchill had his pundits and naysayers in his own time. But he

soldiered on according to his own likes; a true modern-age Trojan if ever one

existed. Whether servicing England abroad, rifle and bayonet firmly in hand, or

on the floor of the House of Commons and supreme, Churchill was never anything

less than the supreme overseer of the nation’s most turbulent times. Just as

Franklin Roosevelt had created an aura around his public persona, as the nation’s

father figure, with his country-wide radio hookups and ‘fireside chats’,

Churchill’s addresses to an England under siege from Hitler’s blitz, proved the

cause célèbre to rally England to its feet and fight on to victory. Director, Richard

Attenborough’s Young Winston (1972) is not particularly interested in that

galvanized cinematic image of Churchill, endlessly revived as the pugnacious PM,

body in decline, with the bulbous face of a bulldog, but rather, the dashing

young man, rarely if ever observed on celluloid who, even at the cusp of his

manhood, stood tall and lean in an era steeped in decorum and gallantry; qualities

thought to have perished with the Second Boer War. Carl Foreman’s screenplay is

based on Churchill’s own My Early Life: A Roving Commission – the 13th

autobiographical installment in a 26-volume account of his life and times.

Attenborough, in the director’s chair for the very first time, has been

entrusted with the task of informing his audience of the epic stature of a man

many only ‘thought’ they knew. On occasion, Attenborough has a rough go

of sticking with his subject, played with uncanny insight by the magnificent

stage actor, Simon Ward. But Attenborough, who has also been given a plum cast,

to include the likes of Jack Hawkins, Jane Seymour, Anthony Hopkins, and Ian

Holm, intermittently seems far more interested in exploring the family dynamic exemplified

by Winston’s mum and dad: Lord ‘Randolph’ and Lady ‘Jennie’ Churchill, carried

off with monumental stature by Robert Shaw and Anne Bancroft respectively.

The first half of Young Winston is a travelogue through Winston’s

discontented school years leading up to the death of his father, and, in spots,

the picture suffers from a lag of impetus to propel the plot onward. We are

introduced to a pair of headmasters; Robert Hardy’s stern educator from Winston’s

prep school, and Hawkins’ James Welldon of Harrow; also, the wonderful Pat Heywood as

Churchill’s nanny and early confidante, Elizabeth Ann Everest. All of the

aforementioned have a personal investment in the shaping of the man who, for

the bulk of this movie, emerges fully-formed in Ward’s accomplished stature as

a sort of staunch, self-anointed, and even more self-possessed individual of

qualities – only some, immediately admirable - but who quickly begins to carve,

then govern, and finally, guide a destiny according to his own likes, and, much

to the chronic chagrin and consternation of Lord Churchill. Despite its hefty

157-minutes (later, to be unceremoniously pared down to 146, then 124-minutes),

Young Winston cannot help but steadily devolve into a faux epic. Part of

the responsibility for this affliction is Attenborough’s inexperience behind

the camera. Young Winston is a series of moving tableau which cumulatively

attempt, but only intermittently succeed, at unearthing Churchill’s driving

core of ambition. If anything, Attenborough’s direction here lacks the same

level of passion Winston Churchill possessed in life, richly unfurled with

handsome production values on the expansive Panavision screen. The rest of the

responsibility here falls on Carl Foreman, whose screenplay becomes ensnared in

the trap of providing loose coverage of the man in his hours of glory and despair.

Let’s face it: an hour in Sir Winston’s shoes is more riveting than most people’s

lifetimes. So, what we have here is the Cole’s Notes’ edition of Churchill’s

exploits in India and the Sudan; his partaking of the cavalry charge at Omdurman,

and, his experiences as a war correspondent during the Second Boer War; a

conflict in which he endured enemy capture, escaped by the skin of his teeth,

and, went on to win his first election to British Parliament at the age of 26!

Young Winston spans the early decades. Anchoring the date, September

16th, 1897, but beginning in the middle, with Churchill, a junior

officer stationed in India and most determined to distinguish himself as a

soldier and statesman, almost immediately, we regress through Ward’s eloquent voice-over

narration, into Winston’s childhood: Churchill, as a boy, briefly played by

Russell Lewis – age 7, and, Michael Audreson – age 13. Sent to boarding school,

Churchill endures excessive whippings from the Headmaster for his perceived

insubordination. He is withdrawn from this formal ‘education’ by his mother –

far more compassionate to his plight than his father, and ensconced, under

Welldon’s tutelage, at Harrow. Defiant to a fault, Churchill refuses to partake

of his entrance examination, committing nothing to paper. Nevertheless, Welldon

is impressed with the lad, recognizing his ‘potential’. And indeed, Churchill’s

intelligence blossoms at Harrow. His recital from memory of a lengthy 1000-line

poem is attended by his ever-devoted nanny; yet, all but ignored by his

parents, whose acceptance Winston is, at first, somewhat anxious to obtain. At

this juncture, Lord Churchill contracts a venereal disease. Jennie is informed

by doctors Roose (Clive Morton) and Buzzard (Robert Flemyn) her husband has

perhaps 5-6 years yet to live.

The eternal struggle of the generation gap continues as Winston, passionate

and slightly pompous, infuriates Randolph, who orders him return to his

bedroom. Softening somewhat shortly thereafter, especially under Jennie’s guidance,

Randolph elects to offer something of a veiled apology for his sternness and

Winston, deeply admiring his father, decides then and there that his future

will be in the military. Alas, Winston is distracted, or perhaps, so far ahead

of his colleagues, he cannot fathom the waste of time it takes to cut through

all the bureaucracy. As such, it takes him three attempts to finally gain

acceptance into Sandhurst. Despite his eventual entrance into this prestigious

Royal Military Academy, Randolph is unimpressed with his son, as Winston has

barely managed to scrape by – ranking seventh, from the bottom of his class.

Randolph chides his son to do better. More is expected of him. He must therefore

demand far more from himself. By now, the undisclosed illness afflicting Lord

Churchill (he is believed to have suffered from syphilis – although he died of

pneumonia) has taken hold. Quietly succumbing to the disease, Winston is

heartbroken that his own dreams of entering British Parliament while his father

reigned as Chancellor of the Exchequer, will remain unfulfilled.

Churchill’s graduation from Sandhurst is therefore bittersweet. But now,

he invests everything he has as a Second Lieutenant, shipped off to India and

the Sudan. Aside: this is presumably where the picture’s great satisfaction

ought to have arisen, with a flourish of valor on full display, via the pageantry

of military might. Alas, Attenborough directs the cavalry charges at the Battle

of Omdurman with a sort of static aplomb – the action, so woefully regimented,

it emerges as a thoroughly weak-kneed reenactment. Instead of a bawdy display

of guts and glory, we are treated to melodrama, dovetailing into Winston’s journey

to South Africa as a war correspondent. En route to his outpost via train,

Winston and the other soldiers are ambushed by Boers, barreling into a

stockpile of rocks on the tracks. Courageously organizing the men to push one

of the damaged cars onward, Churchill and several others are taken prisoner by

the Boers. Determined to escape, Churchill eventually seeks aid from Mr. Howard

(John Woodvine) who helps to smuggled him across the

border. Concealed in a mine for three days, Winston eventually makes his way to

another train, crossing into British-controlled territory and, thus, free to

return to England. Decorated as a war hero, Churchill easily wins the Oldham

election. Our story concludes with another of Churchill’s orations; this one, a

deft summary of his future trajectory and marriage to the affable, Clementine

Hozier (Pippa Steel), seven years later. Newsreel footage makes Churchill’s

triumphant appearance alongside the Royal Family at Buckingham Palace on VE Day,

May 1945.

Nominated for 3 Academy Awards, and proving itself one the most

highly-anticipated, and widely seen pictures in the U.K., Young Winston’s

aegis, at least for screenwriter, Carl Foreman, began with a chance encounter

with none other than the great man himself. Churchill had, in fact, been

impressed with Foreman’s work on The Guns of Navarone (1961). Rather magnanimously,

Churchill suggested his book, ‘My Early Life’ as the template for

another grand epic. Foreman was enthralled to be asked, and effectively announced

to the world he would produce such a picture to star James Fox, who had broken

through to popular appeal on both sides of the Atlantic, thanks to stellar work

in The Servant (1963), Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines

(1965), King Rat (1965), The Chase (1966), Thoroughly Modern

Millie (1967), Isadora (1968), and Performance (1970). Alas,

Fox was not to partake of Young Winston, for reasons never entirely

disclosed. And Foreman, desperate for an actor to promote in the lead, fell to

a superb second choice - Simon Ward; the handsome and accomplished thespian,

son of a

car salesman from Beckenham, Kent, primarily known for his work on the English

stage. With virtually no screen experience, Ward’s performance in Young

Winston nevertheless manages to typify all of the youthful defiance and

self-effacing pride one could imagine coursing through Churchill’s veins.

Indeed, Ward, as Winston, is magnetic, and the picture’s success – particularly

in the U.K., is due largely to his performance, and, effectively, ought to have

launched one of those iconic and formidable movie careers, to be endlessly

revived and discussed decades later. Alas, it was not to be.

Instead, Ward would remain ever-devoted to the stage – his appearances

in films thereafter, distilled largely into forgettable parts - like 1973’s

reboot of The Three Musketeers and its 1974 sequel. Addressing the rare

query regarding his ‘failure’ to take full advantage of the flourish of success

afforded him after Young Winston, Ward joked that he lacked the matinee

profile of a leading man, while being far too young to play character parts –

like ‘the butler’. “I knew I wasn’t going to hack it in Hollywood because

I didn’t look right for American movies. I would have ended up playing

depressed gay marquesses… My nose was not big enough — you need a big nose.”

More to the point, Ward had no stomach

for stardom, and seemingly no ambition to seek out the limelight either. For a

brief wrinkle in time it followed him, with honorable mention to 1974’s All

Creatures Great and Small, 1976’s Aces High and 1979’s Zulu Dawn.

But by 1980, Ward’s screen work had been reduced to trickle. Attacked in the

streets of London in 1987, the details quietly obscured, Ward was left with a

broken skull, requiring brain surgery. This led to polycythemia - a chronic

blood disorder that permanently affected his career. Viewed today, and outside

of Ward’s commanding presence, as well as the appearances of a host of stalwart

Brit-based talents, given short shrift mostly in Foreman’s abridged history of

the great man, Young Winston is more than a bit episodic, even stodgy in

spots. It holds up because the talent behind it is formidably engaged to

deliver a truly awe-inspiring entertainment; Gerry Turpin’s cinematography,

taking full advantage of John Ashton and Geoffrey Drake’s exemplary production

design; also, Anthony Mendleson’s costume design. The pictorial authenticity here

is impressive and was Oscar-nominated, along with Foreman’s screenplay. The net

result is that we do step back for a moment in time, given something less than its

due. Again, Churchill’s life was so rife with stories - great and small - one

could easily dramatize a week’s worth and have enough for a 3-hr. epic. So, at least

in hindsight, it is the girth of the picture that seems to get in the way of

its storytelling. We are taken on a journey, but with a tender

emasculation at play; parts cut, either to satisfy time constraints, or, even

more deliberately, excised for the benefit of our imaginations to run wild.

Either way, Young Winston is a minor epic with some fairly major appeal.

It ought to have been better. Indeed, it ought to have been a mini-series. Ah,

now there’s a good one for Julian Fellowes to tackle next. Hint. Hint.

Advancing at a measured gait, Young Winston marginally suffers

from too much cordiality and not enough action to make it digestible beyond the

occasionally wordy ‘drawing room’ conversation piece. We get two mediocre

battle sequences, separated by interminably long ‘discussions’, a touch of Freudianism

a la Carl Foreman, and owed too much good taste, but precious little excitement

along the way. The picture is imbued with a sort of stately, yet embalmed quality

that works, up to a point; yet strangely, lacks the occasional sentimental vignette

- even moment - necessary to, in tandem, get to the heart of the matter and the

man. Churchill, a highly private individual, never allowing the public any

perception he did not first sanctify and carefully structure as ‘the

performance’ in lieu of his public life, would likely have approved of Young

Winston as it maintains his immaculate façade, unfettered by scandal or

controversy. And yet, somewhere along

the way, Simon Ward lets us a glimpse into this immensely complicated man; a pang expression of paternal dejection here; a hint of awkwardness with the ladies

over there. Foreman’s aversion to veering even a hair out of the Churchill

featured between the pages of his book, lacks the inventive attitude to make

his subject truly a figure of flesh and bone. Lest we remember, movies are not

truth itself, but rather, the illusion of it. The more we can believe in what

we are seeing, the more effective its artistic license and verisimilitude. Even so, one cannot help but admire the

picture’s pedestrian lack of narrative adornment that never gets even close to

probing the rationale of our hero.

Young Winston arrives on Blu-ray via Powerhouse/Indicator in a ‘region

free’ offering that includes the overture, intermission/entr'acte and exit

music. The 2.35:1 Panavision image is, alas, fairly grain-heavy. This is

decidedly not a full-blown restoration, but Sony – the custodians of the film elements,

doing their utmost to preserve the picture in its present state of subtle

decay. I detected some color implosion: flesh that is far too pink, and color

density issues that repeatedly fluctuate from relatively adequate saturation

levels to a wan ghost flower of the image that once was. Close-ups reveal some good

solid fine detail, but long shots tend to get lost in a residual softness with

heavy grain further intruding. There are a few fleeting instances of

age-related artifacts, but nothing egregious. Indicator affords us a PCM mono

audio – adequate, at best, if under-utilizing composer, Alfred Ralston’s

rousing score. Indicator has crammed some really outstanding extras on this

disc: 1971’s John Player Lecture (audio only) with Richard Attenborough running

concurrently for nearly an hour and a half with the movie on an alternative

track. From 2006, we get a 13-minute reflection piece from Attenborough; also, an

archival interview running barely 20 minutes with Simon Ward. Indicator has

also shelled out for a newly produced half-hour conversation piece with

assistant director, William P. Cartlidge and another with second assistant

director, Brian Cook. Stunt double Vic Armstrong chats for a scant 10 minutes,

while John Richardson discusses the SFX and location work for just under 5

minutes. There is also a 3-minute piece

with make-up artist, Robin Grantham. Deleted

scenes from the ‘roadshow’, a theatrical trailer, and, rare footage from the US

premiere in 1972, cap off our enjoyment. Finally, Indicator’s Criterion-styled 36-page

booklet, features a new essay by Sergio Angelini, as well as an extract from My

Early Life: A Roving Commission. Bottom line: Young Winston is

old-time picture-making on a grand scale. While the movie has its failings, its

subject alone – not to mention the extremely fine performances to be gleaned

from within - makes it a compelling experience, if falling just shy of being

considered a true masterpiece. The Blu-ray is adequate - not stellar. Judge and

buy accordingly.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

3.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

3.5

EXTRAS

4.5

Comments