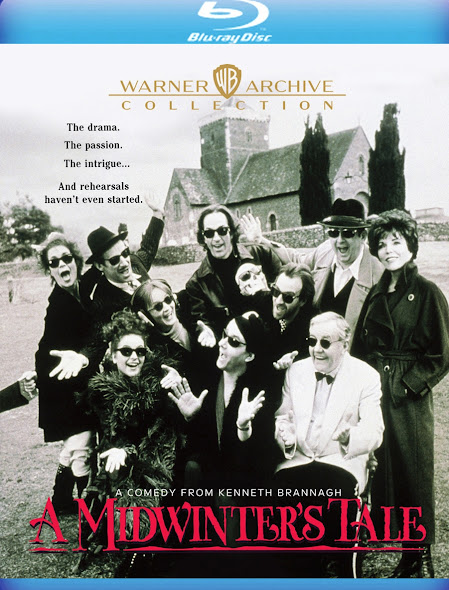

A MIDWINTER'S TALE: Blu-ray (Castlerock, 1995) Warner Archive

Kenneth Branagh

pours some zestful creative juices into A Midwinter’s Tale (1995), a joyously

obtuse, and oft affecting homage to all creatively frustrated geniuses toiling

in the arts. Only in hindsight, does the picture play as a sort of ‘dry run’

for Branagh’s headier aspirations in bringing his all-star celluloid opus

magnum - Hamlet, made and released one year later. However,

as written by Branagh, there is an autobiographical quality at work within this screwball menagerie,

as Midwinter’s aspiring artiste, Joe Harper, harried, yet consumed to become the next Olivier by staging his ultimate ‘experimental’ Hamlet, was an aspiration shared by Branagh, too struggling to make

ends meet only a few years removed from this pic, but elevated to A-lister status after his catapult to

super-stardom following the international release of Henry V (1989). Consider how some of Branagh’s Hamlet cast pre-surfaces in

A Midwinter’s Tale, Branagh, perhaps, using this movie to audition them for the impending masterpiece. Thus, Joe Harper played by Michael Maloney,

plays the doomed Dane herein (a role Branagh would assume for himself in Hamlet),

casting Maloney as Hamlet’s arch nemesis, Laertes in Hamlet,

while Nicholas Farrell – Midwinter’s Tom Newman, a.k.a. Laertes here, would morph into Hamlet’s best friend, Horatio in Hamlet).

Interesting also to see actor, Richard Briers – properly cured English ham,

Richard Wakefield, playing King Claudius here, as he would appear as Polonius

in Branagh’s Hamlet.

Such comparisons

aside, A Midwinter’s Tale is blessed to have a hand-selected troop of

solid performing British thespians at its helm, especially as Branagh, having also written this movie, appears nowhere in it. So, the marquee-drawing

power of Branagh’s name alone must suffice for North American audiences. It does; though largely because the cast here

is accomplished in ways most American talent appearing on big screens

these days can only guess at play-acting. Anyone with even a light smattering of knowledge

or an affinity for British television and films will be able to pick out their

favorites at a glance from this impressive line-up; starting with Joan Collins as

Joe’s catty agent, Margaretta D'Arcy. Collins began her career in the

mid-fifties as a sex bomb that, arguably, was never entirely to detonate on movie

canvas, in part thanks to bad timing and even more tepid parts that did little

to create an indelible impression with fans. Instead, her legend arose like the

proverbial phoenix, playing uber-bitch in heels, Alexis Morrell/Carrington/Colby/Dexter

on TV’s primetime soap, Dynasty, decades later. Also put to exceptional

good use, actress, Julia Sawalha (most fondly recalled as Saffy on TV’s Absolutely

Fabulous) herein, as Nina Raymond (a.k.a. Ophelia), Joe’s rather myopically-focused, though well-intended love interest; Celia Imrie, whose own storied

career has included many high-profile appearances on stage, screen and

television too numerous to list, as Fadge, Joe’s set and costume designer; the

marvelous and incredibly seasoned, Gerard Horan as boozy bachelor,

Carnforth Greville (whose real name in this movie is Keith Branch), cast as Rosencrantz,

Guildenstern, Horatio, and Barnardo), the superbly ribald, John Sessions as

flamer, Terry Du Bois (cast as Queen Gertrude), and, finally, Jennifer Saunders

(of French and Saunders’ fame) herein, playing bitchy American

producer, Nancy Crawford whom Joe turns down for a multi-picture deal, but who takes an

immediate liking to Nicholas Farrell’s buff and shirtless, Laertes.

After the most

rudimentary main titles, our store opens with Joe Harper, a desperately

downtrodden actor begging his agent, Margaretta D'Arcy to finance his

Christmastime production of Hamlet in his hometown of Hope, Derbyshire with

himself cast in the lead. After some initial cajoling, D’Arcy agrees. Alas, the

auditions draw out a cacophony of odd, impassioned, occasionally deranged and

loveably blunt reprobates, utterly to sour D’Arcy on the whole affair. Undaunted,

Joe casts six actors to fulfill his dream project: kindly, but scattershot, Nina

Raymond; cynical ham, Henry Wakefield, unreservedly brash homosexual, Terry

DuBois; vanity-stricken Tom Newman; boozy Carnforth Greville, and, ex-child

star, Vernon Spatch (Mark Hadfield). Also recruited to the cause, Joe’s sister,

Molly (Hetta Charnley) and a friend, Fadge, a flighty costume and set designer in

charge of resurrecting a derelict cathedral, slated for demolition, into the

stagecraft settings of the play. Despite the skinflint operations – Joe barely

has enough to cover meals and the rental of the property – the actors dig in

and rehearsals begin. Fearing the audience will not turn out to see the play,

Fadge also creates various cardboard figures as substitutes.

From the outset,

Joe has an uphill struggle with his cast. Some fail to get along with the

others. Most are ill-prepared to rise to the occasion in the roles they have

been selected to perform. Carnforth, as example, hits the bottle – hard – and

cannot remember his lines. Tom insists on using outrageous accents. Henry

detests Terry. And Nina's bad eyesight causes her to take a header off the

altar steps, fracturing her skull. At the eleventh hour, Joe and Molly attempt

to juggle the budget to accommodate a greedy landlord who now demands an extra

week’s rent they cannot pay. The cast rally to Joe’s aid, selling off

possessions and giving what they can to extend their time to rehearse and prepare.

Vernon begins to aggressively promote the play with hand-printed flyers and

selling tickets on the streets and at a hotel. Alas, as ‘the play’s the thing’,

and nothing here seems to be working out, several of the cast members suffer a

crisis of conscience. At one point, Tom has a meltdown over Carnforth's flubbing

his dialogue. Joe snaps and suggests everyone simply go home for good. Eventually, cooler heads prevail. However, as

Christmas Eve fast approaches, D’Arcy informs Joe he has been given a rare, and

highly lucrative opportunity by American producer, Nancy Crawford to direct a sci-fi

trilogy. The catch: Joe has to start work on the first installment immediately.

This leaves the play without its Hamlet.

The cast

struggle to reconcile their own feelings about the play and the loss of its

driving force with what would be best for Joe. All except Nina concur Joe should

go off to America to make his reputation and fortunes. And thus, Joe

momentarily departs, leaving Nina frantic and angry. All, however, is not lost.

On opening night, just as Molly is preparing to debut in her brother’s stead as

the infamous Dane, Joe materializes from the crowd. Evidently, he turned

Crawford down. Intrigued by the reasons a nobody like Joe would sacrifice his

one chance to become an international success, Crawford attends the play along

with D’Arcy. Each is pleasantly

surprised when the cast, with Joe playing Hamlet, pull off a daring success

that brings the audience to its feet. The superficial Crawford is drawn to Tom

who has played the duel between Hamlet and Laertes shirtless. She offers him a

role in her sci-fi trilogy. D’Arcy immediately snatches up the opportunity to

become Tom’s agent. Nina and Joe are reconciled while Carnforth is reunited

with his mother (Ann Davies), who insists how proud she is of him. Terry gets

to share a heartfelt moment with his estranged son, Tim (James D. White) whom

Henry managed to get to the theater by lying that his father is dying of cholera.

And thus, all’s well that ends well.

At the crux of A

Midwinter’s Tale is Branagh’s delicious insider’s verve for exposing the mania, joy and chaos that arises backstage when people are brought

together from disparate backgrounds, fervently uniting in their singular desire

to ‘put on a show’ and perhaps, find their own place in and out of the pall of

the spotlight. Borrowing a chapter from Woody Allen, Branagh structures his

story around inserted title cards to illustrate the progression of

the exercise in bringing art to life and vice versa. Like Allen, Branagh also

has made the daring executive decision to shoot A Midwinter’s Tale in B&W - even more of a gamble in 1995, though not unprecedented after the Oscar-winning success of 1993's Schindler's List. While poster art for A Midwinter's Tale declared it as ‘Spinal Tap’ for

Shakespeare lovers, Branagh’s picture is far from a nice and tidy, little comedy

about theater folk bringing the bard to town, or even the toils endured along

that bumpy road to success. Rather, in its ensemble, A Midwinter’s Tale

is more centrally focused on the way artistic endeavor

impacts and enriches the lives of those involved in its fruition. As example, there

is something genuinely affecting and tender about the way the initial

animosity struck between homophobic, Richard and unapologetically flamboyant,

Terry incrementally dissolves after the former discovers the latter is

estranged from his adult son – a situation Richard rectifies by inviting the

son to partake of their Christmas Eve live performance. But perhaps

the greatest tragedy unfurled was at the box office. A Midwinter’s Tale

failed to gel with audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. Despite high praise

from some of cinema’s most astute cultural mandarins, as well as being a competitive entry

at the 52nd Venice International Film Festival, and, winning Branagh

the Golden Osella for Best Director, A Midwinter’s Tale grossed a

disappointing £235,302 in its native Britain and barely $469,571 in the U.S. and

Canada. As a result, it quickly disappeared off movie marquees. In the

interceding decades, A Midwinter’s Tale has acquired a reputation as a

cult classic. But really, it deserves much higher recognition than this.

The Warner

Archive (WAC) releases a stunningly handsome new-to-Blu of A Midwinter’s Tale,

originally under the now defunct ‘Castlerock’ distribution label, and, properly

framed in 1.66:1, showing off Roger Lanser’s exquisitely-lit B&W

cinematography to its very best advantage. Given the film’s scant budget,

production designer, Tim Harvey always gives us something interesting to look

at, while costumer, Caroline Harris makes the most out of some eclectic

fashions that, in part, being so utterly absurd, have not dated a bit in the

intervening decades. It all looks gorgeous here, with deep, rich and enveloping

blacks, pristine whites, proper contrast and a light smattering of film grain

appearing very indigenous to its source. The DTS 2.0 soundtrack is clean,

although some dialogue is indecipherable at lower decibel levels. Extras are

limited to a theatrical trailer. Bottom line: A Midwinter’s Tale is very

much of the ‘little gem’ class in dramedies that a Brit-based studio like

Ealing used to pump out throughout the forties and fifties with great success.

Branagh gilds this lily with solidly crafted performances and an expertly

structured screenplay that effortlessly runs the gamut of emotions from tragic

to comedic in barely 98 minutes of sheer joy for the love of the craft of

acting, and more directly, for doing it all with great finesse and class.

Shakespeare would be so very proud!

FILM RATING (out

of 5 – 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

5+

EXTRAS

0

Comments