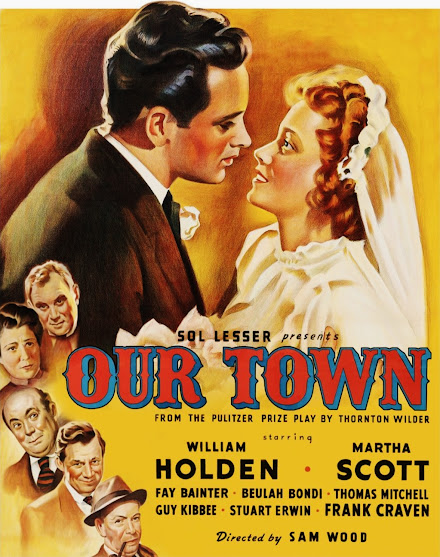

OUR TOWN: Blu-ray (UA, Sol Lesser, 1940) ClassicFlix

Walter Winchell once astutely

proclaimed that the quickest route to attaining fame was to throw a brick at

somebody famous. And quite likely no other reason why tattoo artist and porn

peddler, Samuel Steward would lay claim to a homoerotic affair with playwright,

Thornton Wilder – the lit-wit luminary who gave us such prized and eternally

satisfying achievements as the Pulitzer prize-winning classics, The Bridges

of San Luis Rey (first published in 1927), Our Town (the play, 1938) and, The

Skin of Our Teeth (1942), and, The Matchmaker (1954, noteworthy in

and of itself, but also, and much later, to morph into the musical colossus, Hello

Dolly!). Steward’s claim has been simultaneously corroborated and refuted

by those either seeking to exploit and sensationalize Wilder’s own conflicted

sexuality – duly noted – or protect his reputation by adding to the misguided

notion there was nothing queer about him at all. Anyone seeking truth as to Wilder’s

all too human condition, however, need look no further than to Wilder’s

formidable contributions in literature and on the stage. For he seemed, in

tandem, not only to be acutely tuned to the common fallacies humanity uses to

quell its own social anxieties, but also to acknowledge the unlikelihood that

any human-concocted foible could so thoroughly discredit one’s place within the

ever-evolving structure of life on this planet. Besides, Steward’s claim was

made six-years after Wilder’s death from heart failure, enough to allow his

reputation to ripen and endure, rather than mellow and molder with the passage

of time.

To suggest Wilder came from a

family of creatives is to put things mildly. His elder brother, Amos Niven was

a noted poet, instrumental in developing theopoetics, while sis’s, Isabel and

Charlotte were accomplished writers, and, sister, Janet struck out as an

accomplished zoologist. From earnings made off The Bridge of San Luis Rey,

an antecedent

of the modern disaster epic, Wilder had a house built in Hamden, Connecticut – home

base for his creative juices to charge and flow. He shared this estate with

Isabel for the rest of their lives. Like all truly enlightened men, Wilder used

his travels abroad as introspective studies to learn the ways of the world

beyond his own comfort zone. Proficient in four languages, during WWII, Wilder

served as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Air Force Intelligence, and afterward,

became a ‘visiting professor’ at Harvard University. In 1957, he received the Peace

Prize of the German Book Trade, followed by the Presidential Medal of Freedom

in 1963 and National Book Award for his 1968 novel, The Eighth Day. All

in all, one hell of a renaissance man. And this is just the tip of a very

formidable list of accomplishments that continue to resonate with modern

audiences in spite of changing tastes and times.

Conversely, film director, Sam Wood

had been a real estate broker before the great stock market collapse of 1929.

If not for this, and

also, his marriage to Clara Louise Roush, who encouraged a change of venue

after the market bottomed out, Wood might never have seen the inside of a film

studio, much less become one of the foremost contributors to the ‘then’

burgeoning art of motion picture entertainment. Wood quickly rose to prominence

in the industry, courted by all the major stars of his generation and known throughout

as being accomplished and efficient within the confines of the studio system. His mid-to-late thirties output alone, reads

like a veritable hit parade with such enduring masterpieces as the Gable/Harlow

romancer, Hold Your Man (1933), two of the Marx Bros. greatest comedies,

A Night at the Opera (1935), and, A Day at the Races (1936), and,

the handsomely mounted tearjerker/drama, Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939), made

while also shooting second unit on David O. Selznick’s Gone with the Wind

(1939). His forties output is no less impressive; Our Town, as well as

the Oscar-winning, Kitty Foyle (both in 1940), King’s Row, and, The

Pride of the Yankees (both in 1942), the costly war epic, For Whom the

Bell Tolls (1944, on loan to Universal) and, MGM’s all-star, WWII actioner,

Command Decision (1949).

Produced independently by Sol

Lesser under a distribution deal with United Artists, Our Town remains a

tenderly poignant and faithful adaptation of Thornton Wilder’s lithe and

lyrical stagecraft. After some consternation, Martha Scott was cast as Emily

Webb, her film debut nearly derailed by a horrendous screen test made the year

before for the part of Melanie Hamilton in Gone with the Wind. Aside:

that role eventually went to Olivia DeHavilland. Cast opposite Scott as love

interest George Gibbs was William Holden, fresh off his success in 1939’s Golden

Boy. Like Scott, Holden almost lost out on his career-changing moment,

rescued in the eleventh hour by his co-star with clout, Barbara Stanwyck, who

spent the rest of its shoot encouraging his young talent to mature – a kindness

Holden publicly acknowledge decades later at the 78th annual Oscar telecast.

Like all movies produced during this golden vintage, Our Town is the

recipient of some very fine and familiar character actors of their generation

doing what they did best: Fay Bainter as George’s doating mama, Julia, Beulah

Bondi (as Emily’s mom, Myrtle), Thomas Mitchell (Frank F. Gibb), and, Guy

Kibbee (Charles Webb).

The strength of the piece is not

reserved to its roster of skilled thespians, however, but in the way director,

Sam Wood gingerly winds his way into the heart of Thornton Wilder’s stagecraft,

subtly opening things up to satisfy the requirements of a motion picture, and

even creating two complete departures from it, yet without ever loosening his

grasp on the artistry that made the play so understatedly affecting and famous.

The first monumental alteration to Wilder’s show is in the staging. The

stagecraft was performed on a blank proscenium. The movie, understandably, adds

props and scenery – a forgivable necessity of the medium. But the other change

is more startling; the third act finale, in which an ailing Martha is restored

to health after succumbing momentarily to a dream sequence. In the play, Martha

actually dies and her reunion with various friends and family having passed

into the afterlife before her is portrayed as part of her ascendance into the

heavens. Far from objecting to these alterations, Wilder actually encouraged

them, particularly Emily’s survival and restoration to the world of the living,

adding in a letter to producer, Sol Lesser, “Emily should live. In a movie

you see the people so close to, that a different relation is established. In

the theater, they are halfway abstractions in an allegory. In the movie they

are very concrete. It is disproportionately cruel that she dies. Let her live.”

On the surface at least, the plot

to Our Town is so utterly simplistic, at first it appears rudimentary. In

the idyllic enclave of Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire, we are swiftly

introduced to elderly Dr. Gibbs, his wife, Julie and their two children, George

and Rebecca (Ruth Toby). The Gibbs are a gentle and united family, neighboring

the Webbs, who have a handsome daughter, Emily, and younger son, Wally (Douglas

Gardiner). As fate would have it, George and Emily fall in love, court and are

eventually wed. The bulk of the first two acts is devoted to the evolution of

their affections for each other. Act three is where it all gets interesting. Time

passes and all is well until Emily is stricken with a near-fatal illness after

the birth of their second child. Lingering between death and the angels, Emily

begins to encounter the many friends and family who have left this world in the

years before. Each plays an affecting role in encouraging her to triumph over

this ‘life and death’ limbo. As such, Emily eventually awakens from what she

later perceives as a dream, returning to George and her children, renewed in

spirit and physical strength.

Our Town is a miracle of

concise and precise execution. There is not a frame to spare in the production.

Sam Wood’s direction is but one virtue here, eliciting great performances from

his expertly assembled ensemble. The rest is owed production designer, William

Cameron Menzies, cinematographer, Bert Glennon and composer, Aaron Copland –

each, at the pinnacle of their powers in their respective fields. Copland’s

score is particularly affecting and would be Oscar-nominated. What is most

engaging about the movie when viewed today is how seamlessly all of its pieces

come together to create a gentle, absorbing and loving portrait of small-town Americana

at its very best and most naïvely innocent. This is the America of a

Frank Capra movie, tweaked to produce a less heightened, though no less

affecting sense of poignancy and realism, imbued with all the optimism and

moral strength of character one used to readily find and sincerely embrace in

American society at large. That even the concept of it, and/or morality has so

completely withered, or rather, morphed into something more darkly purposed in

recent times, speaks to our collective idealism turned asunder. And yet, even

under the yoke of our present cynical epoch, Our Town reigns as a truly

heartwarming tale for which virtue truly is its own reward. The final act is

satisfying beyond expectations. It stirs the soul to reconsider what once was,

what has since been lost, and perhaps, what can be again in a world in which

all lives matter, and, faith in the future is more genuine and palpable than

the cynicism that oft creeps in to obfuscate its virtue.

Our Town has been

meticulously restored by ClassicFlix.

Owing to a lapse in rights since the late 1970’s, the picture’s ‘public

domain’ status has resulted in many a bootleg looking far worse for the wear

than any movie has a right, and, even worse, countless reincarnations

professing to remastering efforts simply, never to have taken place. ClassicFlix’s

release of Our Town is the real deal, derived from a surviving 35mm

print housed at the Library of Congress. Contrast takes a quantum leap forward.

Gray scale tonality is markedly improved.

Age-related ‘wear and tear’ has been eradicated. And a light smattering

of film grain appears indigenous to its source. The DTS 2.0 mono audio

preserves dialogue with a crisp refinement, complimented by Aaron Copland’s

Oscar-nominated score. Ray Faiola provides an expert commentary covering the

film’s production history. From 1953, we get an interview with Thornton Wilder,

hosted by Lilli Palmer, as well as two radio broadcasts – the first in 1939,

featuring Orson Welles, Ray Collins, Everett Sloane and Agnes Moorehead, the

second, from 1940, with the movie’s cast, including William Holden, Martha

Scott, Fay Bainter, Beulah Bondi, Thomas Mitchell, Guy Kibbee and Stuart Erwin

reprising their respective roles.

Finally, there’s a restoration comparison and trailers for other

ClassicFlix product. Bottom line: Our Town is a quintessentially American

charmer featuring excellent performances in a heartwarming tale. This Blu-ray

is an exceptional upgrade. Highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out

of 5 – 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

3

Comments