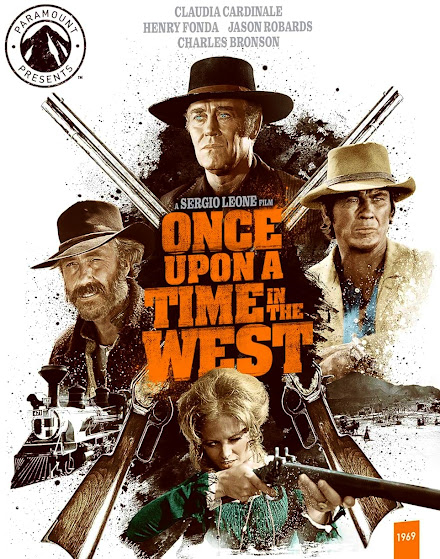

ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST: 4K UHD Blu-ray (Paramount/Euro International, 1968) Paramount Home Video

Serendipity has

always played a big part in life as well as the movies, perhaps nowhere as evidently

than with director, Sergio Leone's seminal spaghetti western, Once Upon A

Time in The West (1968). After 1966’s The Good, The Bad and The Ugly,

Leone, a man of few words - potently placed (often with glib satire), publicly

announced his retirement from the western genre. Offers came and went. But

Leone remained staunchly determined in his refusals. That is, until Paramount

offered him a substantial budget and access to Henry Fonda, Leone's all-time

favorite star with whom he had never worked before. At Leone's request,

Bernardo Bertolucci and Dario Argento were brought in to develop the property

in 1966, spending almost a year watching, then deconstructing classic Hollywood

westerns for inspiration. Conscious, his glacial approach to story-telling was

being severely paired down for general release in America, Leone commissioned

Sergio Donati to help refine and edit the working script to minimize outside

tampering with his original vision. Nevertheless, when Once Upon a Time in

the West had its U.S. theatrical debut, it was shorn of nearly 21-mins.

For Once Upon

A Time in the West, Leone broke many traditions, even some of his own;

including a decidedly more somber tone, as well as allowing his characters to

evolve and mature on screen. There is lots of gunfighting, and plenty of bloodshed.

But Leone’s principles are left standing once the dust has settled -

representatives of the impending transformation and irreversible taming of the

wilderness. Leone's testament here, is to the flesh and blood hiding behind the

legends of their time, without guile or the preservation of their myths. In Leone’s

west, men fail and women come to admire them, not for their accomplishments, rather,

their abject refusal to surrender, even when the battle is lost. As such, Once

Upon A Time in the West stands at a crossroads in the western genre,

bridging the ancient tradition of the gallant astride his noble steed, with a far

more contemporary bent for accidental heroism exhibited in spite of less altruistic

motives. The people who inhabit Leone’s west are real, precisely because they are

rendered from a primal state of fear, arousal, pleasure and meanness. They claw

and bite, betray and befall, only to rise up, showing off their battle scars as

hard-won badges of stubbornness – not, honor.

Always more

interested in the rituals preceding violence than the acts of violence, Donati

and Leone's screenplay for Once Upon A Time in the West delays these outbursts

with carefully calculated sequences, written in the sparsest of dialogue and

even lengthier build-ups, leaning on terrific dread. The casting of Henry Fonda

as the antithesis of that quiet everyman he so often appeared as under the

auspices of directors like Henry King and Howard Hawks, is a stroke of genius on

Leone’s part, compounded by Fonda’s obvious joy at internalizing the evilness

of his ‘man in black’ alter ego. Interestingly, Fonda did not initially

gravitate to the role. Undaunted, Leone flew to New York to implore the actor

to reconsider. Once Upon A Time in the West would never have come about

without Fonda’s participation. Before committing to the project, Fonda telephoned

his friend, Eli Wallach (an alumni of several Leone westerns). Wallach’s advice,

“Do it! You’ll have the time of your life!” finally convinced Fonda to

take the leap of faith. Alas, when he arrived to greet Leone, Fonda sported a

pair of contact lenses to make his eyes dark, and a menacing moustache.

Repulsed, Leone ordered Fonda to revert to his regular clean-shaven looks and

piercing blue eyes. “I don’t want a cliché for a villain,” Leone reportedly

told his star.

Leone had hoped

to cast Clint Eastwood as Harmonica. Eastwood, however, was disinterested. He

and Leone had clashed on their last collaborative effort. So, possibly,

Eastwood still held a grudge. More likely, Eastwood was enjoying his first

flourish of independence, having already segued into the director’s chair with

the establishment of his own production company, Malpaso in 1967. Leone tried

to get Eastwood to commit to playing one of the three gunslingers who meet, and,

are subsequently gunned down by Harmonica at the railway station. Leone’s aim

here was to cast Wallach and Lee Van Cleef as the remaining pair, thereupon

putting a definite period to his earlier ‘Man With No Name’ trilogy. Though

Wallach was eager and willing, Eastwood could not be cajoled to partake, even in

a cameo. Van Cleef proved unavailable due to prior commitments. And thus, no

finale to their fictional alter egos was possible. The rest of the principles

in Once Upon a Time in the West were rounded out by veterans, ensuring

Leone could concentrate most intensely on the rhythm and style of the picture. Reportedly,

the only reason the director hired Claudia Cardinale was to mine her

participation as an Italian national for its tax breaks. The final bit of

integral casting was behind the camera: composer, Ennio Morricone, whose

previous collaborations with Leone augmented the raw splendor and spice of Leone’s

visual tomes. Cribbing from their past collaborations, Morricone’s leitmotifs

in Once Upon a Time in the West relate to individual characters, with Italian

singer, Edda Dell'Orso wordless vocals on the Jill McBain theme serving as the

movie’s musical centerpiece.

Our story is

concerned with two epic showdowns in the fictional town of Flagstone (actually

an amalgam of locations shot by cinematographer, Tonino Delli Colliin in Spain

and Utah). The first is the cold-blooded murder of Jill McBain’s (Claudia

Cardinale) entire family. The impetus for all the carnage is a parcel of land

known as Sweetwater, bought by Brett McBain (Frank Wolff), a settler who

foresaw a way to capitalize on the coming railroad. Desiring Sweetwater for

himself, the railroad's crippled baron, Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti) sends his

hired gun, Frank (Henry Fonda) and a posse to intimidate McBain and lay claim

to the property. Instead, Frank takes considerable pleasure in killing McBain

and his family (father, and three young children) while planting evidence to

suggest a local bandit, Cheyenne (Jason Robards) is responsible for these murders.

Earlier, Frank also sent three of his best men to the station to meet Harmonica

(Charles Bronson) - a mystery man, and, the only gun capable of challenging Frank’s

supremacy. Dispatching with Frank's men in short order, Harmonica meets up with

Cheyenne in a cantina and informs him, he is being set up by Frank. Meanwhile,

McBain's new bride, Jill (Claudia Cardinale) arrives too late in Flagstone, and,

is met by the town's folk preparing the family’s funerals.

Harmonica and

Cheyenne become smitten with Jill. Harmonica explains to Cheyenne, unless the

station is built by the time the tracks reach the McBain property, Jill will

lose Sweetwater. Cheyenne puts his men to work to build Jill her station.

Outraged at Frank for having defied him, Morton offers Jill a deal on her

property. This betrayal turns mate against master with the die cast for a

brutal confrontation. Frank rapes Jill, then, forces her to sell off Sweetwater

in an auction, believing he will be its only bidder. Instead, Harmonica holds

Cheyenne at gunpoint to make his own bid for the land. Harmonica then sells

Sweetwater back to Jill. Paid by Morton, Frank's men ride to kill Harmonica.

Only Harmonica now comes to Frank's defense, so he may have the privilege of

killing Frank himself. During their final showdown, Frank demands Harmonica

identify himself. In a flashback, we learn Frank killed Harmonica's older

brother by tying a noose around his neck and forcing Harmonica - then a mere

boy - to support him on his shoulders, knowing the child would be unable to do so

indefinitely. Harmonica shoots Frank dead and places a harmonica in his mouth,

making his revenge complete. Her arch nemesis removed Jill supervises

construction of the depot as the first train comes through. Cheyenne reveals to

Harmonica, during his earlier confrontation with Morton's men, he has been

mortally wounded. He collapses and dies in Harmonica's arms, carried into the

sunset by Harmonica as the railroad – that perennial symbol of hope and

progress in the western milieu - looms large in the foreground.

From a purely

narrative perspective, Once Upon A Time in the West is an imperfect movie.

Yet, this is part, if not all of its charm, and, virtually the entire reason

why it ought to be considered a bona fide masterpiece for the ages. Leone is a

confident storyteller. Well aware he is working with an incongruous history,

and even more acutely in tune that no life is a garden without weeds, herein, Leone

bravely forges a narrative populated by ugly, indeterminate figures who lack

the wherewithal to know they are in a movie. The verisimilitude on tap in Once

Upon a Time in the West is genuine because it is genuinely haunting – and

imperfect. Having the bandit, Cheyenne as our self-sacrificing figure in

the end is extremely problematic. If he is a bandit, we never see

Cheyenne at his most ruthless. And, if not, or perhaps, merely out of practice,

then Cheyenne gives more than a fleeting inference that a remarkable

reformation to his character…or lack thereof, has occurred. Perhaps, there is a

little Don Quixote in Cheyenne - the over-the-hill nobleman sheathed in an aura

of his own pretend. It is also rather unlikely, having seen the

cold-blooded-ness of Frank firsthand, that his men, governed by fear, never to

cross the boss, would suddenly forget themselves for a few pieces of silver from

Morton or anyone else. Like Leone’s other spaghetti westerns, the trick and the

magic here is all on the side of style. Substance is tried, but it never sticks,

other than to the superb characterizations brought forth by our stars, whose

presence is an eclipse of their fictional alter egos.

Two tragedies

marred the production. The first involved actor, Al Mulock who played a

supporting role as Knuckles in the film's opening confrontation between

Harmonica and Frank's men. The actor committed suicide by leaping from his

hotel balcony in full costume shortly after his scenes had been shot in Spain.

Two years later, Frank Wolff (McBain) followed Mulock's lead, jumping from his

hotel suite in Rome. As Leone suspected, his 166-minute international cut was pared

down by 22 mins. for the American release. While Once Upon A Time in the

West rang registers in the foreign markets, in America it did a belly-flop

at the box office. Leone blamed this on the cuts. Viewed today, and, in its complete

assembly, Once Upon a Time in the West remains an exemplar of the

revisionist western genre. One cannot help but admire the brilliant touches in

Leone's sustained pacing. The picture is driven and almost entirely sustained

by its peerless performances. While Tonino Delli Colli’s Techniscope cinematography

teems in fascinating compositions, generous in their scope, with each passing

decade, Once Upon A Time in the West seems ever-more the

character-dependent drama whose intimate story, set against a vast canvas, is

mere icing on an already well-frosted cake. Claudia Cardinale – Leone’s token

estrogen in this male-dominated and inhospitable panorama of blood and dust –

strikes an indelible chord as the defiant firebrand, bloodied but unbowed, and,

arguably, the promised future. More than any other Leone western, Once Upon

a Time in the West is less about focusing the plot than presenting us with

a truly awe-inspiring experience of the American west as a western fantasia,

imbued with sobering glimmers for a way of life – hell-bound and lawless – yet

destined to give way to the dawn of the 20th century.

As previously

mentioned, Once Upon a Time on the West was shot in 2-perf Techniscope,

utilizing half the vertical area of conventional 35mm film stocks, and, in a

dye-transfer process that mellowed grain and fine detail. Techniscope was a

more economical way to shoot movies, even with conversion to standardized formats

for distribution, as half the usual stock could be stretched to accommodate the

same feature-length production with far less negative to develop. It also yielded

an image technically superior to Cinemascope, employing spherical lenses. A

minor setback in conversion from 2 to 4-perf (for standard theatrical

distribution) was the amplification of grain, especially when enlarging the image

optically, resulting in a generation loss, exaggerated grain levels, and, overall

downtick in image clarity. But the advantage here is 2-perf can go straight to

digital, thereby cancelling out the 2 to 4-perf loss in image quality.

Restored and

remastered from an OCN in 4K, with HDR and Dolby Vision options, the results in

UHD are decidedly different than the 2011 remastered Blu. Color grading gets a

huge uptick. The primarily ‘earth tone’ palette looks exquisite. Saturation is

excellent and overall tonality could not be better. But the image is decidedly

softer in appearance overall, which may or may not cause fans some

consternation. The 2011 Blu was digitally sharpened. No question about

it. And contrast, which appeared slightly blown out in 2011, is now much more

refined. But fine detail seems to have regressed, particularly in darkly lit scenes.

The ‘go to’ culprit, excessive DNR, doesn’t seem to fit. Instead, it appears as

though video compression is at fault…perhaps. To be clear, whatever ‘grain management’ process

has been applied herein by Paramount, it has not eradicated film grain; rather,

to taper its effect in such a way as to homogenize image quality rather than

preserve its original integrity.

Paramount may be attempting to placate more contemporary tastes which

seem to regard film grain in general as an anathema to one’s overall enjoyment for

appreciating movies shot in the pre-digital era. And to be clearer still, the

application itself has not deprived us of visible texturing and other subtle

nuances in Tonino Delli Colli’s cinematography. Close-ups are extraordinary

while wide angle, long shots differ slightly in overall depth and sharpness. Again, grain is present. But it

intermittently appears thicker than necessary – an oddity, for sure.

Paramount hasn’t

upgraded the audio. It’s a direct port over of the 5.1 and 2.0 lossless DTS

offerings from 2011. While the 5.1 offers obvious spatial separation, the 2.0

delivers a charming ‘vintage’ experience. The 4K disc contains NO extras. But

the Blu (also re-mastered) houses two audio commentaries; the first from Jay

Jennings and Tom Betts, the second by Sir Christopher Frayling, Dr. Sheldon

Hall and Lancelot Narayan. Paramount has also ported over the vintage

featurettes from the old Blu – so, Leonard Maltin’s intro, the half-hour ‘Opera

of Violence’ and almost 20 min. ‘Wages of Sin’, ‘Something to Do

with Death’, and fleeting reflections on the west, the railroad, the

locations, a trailer, and, a photo gallery. Paramount has shorn this remastered

edition of the ‘shorter’ theatrical cut. It was included on the 2011

Blu. Bottom line: few films, and fewer

westerns, reign with such story-telling superiority in a class apart. Once Upon a Time in the West is among

this handful. Alas, the 4K, while remarkable in many regards, is still not altogether

satisfying. Judge and buy accordingly.

FILM RATING (out

of 5 - 5 being the best)

5+

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

3.5

Comments