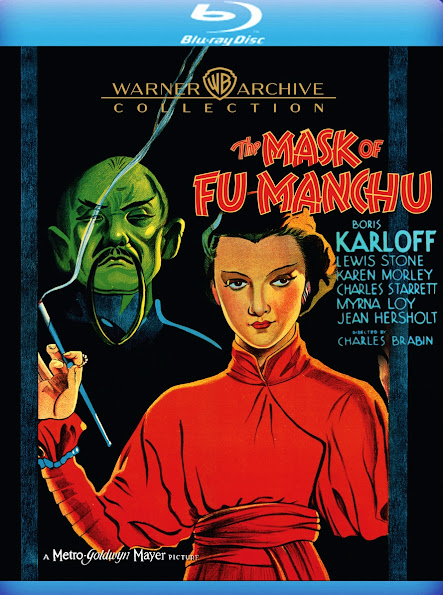

THE MASK OF FU MANCHU: Blu-ray (MGM, 1932) Warner Archive

Birmingham-born

author, Sax Rohmer was a rather unabashed self-promoter. It helped that his

formative years were spent shilling for London’s music hall crowds as a poet,

songwriter and comedy sketch writer where artful fiction readily clouded truth

and better judgements in good taste. Turning to authorship, Rohmer invented his

most enduring creation, Dr. Fu Manchu in 1912 – a culmination of the prevailing

animus towards Asians, in support of the ‘then’ wildly popular theory regarding

the ‘Yellow Peril’. Adopting traditional Chinese garb in his personal grooming,

Rohmer went on to pen 3 additional Fu Manchu novels between 1913 and 1917 becoming

one of the richest authors of his time. Even so, a lengthy, self-imposed hiatus

followed, rumored to promote Rohmer’s Si-Fan Mysteries. But by 1931, Fu

Manchu was ripe for resurrection, this time in a rather shoddy departure from

the original franchise in which Rohmer strained to make Fu Manchu’s daughter

the successor to her father’s mantel of evil tragedy. Yet, this failed to

impress even Rohmer’s artistic bent.

And thus, Rohmer’s

subsequent stories to feature Fu Manchu would hark back to the various

supporting cast he had first introduced, the most celebrated of these, Denis

Nayland Smith, newly knighted and sufficiently aged to keep up with the times.

For the remainder of the series, and, Rohmer’s life, Fu Manchu would stay

faithful to his roots. Rohmer committed 10 more novels, each accounting the atrocities

perpetuated by his most beloved arch villain. And although Rohmer was heavily

criticized for his brazenly made-up, casual and careless impressions of

London's Chinese community, every one of his Fu Manchu novels became a top

seller, garnering scores of readers and legions of fans. Even so, Rohmer tired of

the franchise once again, departing with forays into the supernatural and

horror before resurrecting Fu Manchu one last time for the BBC’s radio ‘Light

Programme’ where it ran from war’s end until 1949. Rather poignantly,

Rohmer would die from the Asian flu in 1959, age 76.

Rohmer had

always held dear that his inspiration for Fu Manchu came from bearing witness

to a dope-smuggler in London’s old Chinatown. But this has been debunked in

more recent times. One thing is for

certain. By the time Boris Karloff donned an elaborate 2-hour make-up to reincarnate

the character for 1932’s The Mask of Fu Manchu, Rohmer’s wicked deviant –

part mad-scientist/part power-driven oligarch – was everywhere. Two Brit-based

silent adaptations and one early Paramount talkie preceded director, Charles

Brabin’s lavishly appointed MGM outing. Interesting too, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

should be the studio to put Fu Manchu on the map, mostly by going against Hollywood’s

burgeoning code of censorship. Having seen the promise in Universal’s profitable

horror cycle, Dracula and Frankenstein (each made and released

the previous year), MGM V.P. Irving Thalberg reasoned there was much to plumb

from the genre on their own backlot. After all, MGM was widely regarded as the

Tiffany of all Hollywood majors. Curiously, Thalberg’s quest to outclass

Universal’s supremacy here, rapidly establishing itself as Hollywood’s Transylvania,

did not achieve its desired effect.

Importing Uni’ director,

Todd Browning to make Freaks (1932) proved an unmitigated disaster for

MGM; the resultant movie deemed too grotesque and shocking for audiences to

digest. Undaunted, and still hopeful to master horror on his terms, on The

Mask of Fu Manchu, Thalberg afforded director, Charles Brabin all the ersatz

American chinoiserie the studio could muster, with art director, Cedric Gibbons

delivering the goods on several gargantuan set pieces, including a ‘bell

torture’ sequence (cut, or at least, pruned by various censorship boards,

though more for Fu Manchu’s overt homosexual revelry), a Barnum and Bailey-styled

assassination at knifepoint, performed from a tightrope at midnight, and, the

picture’s Frankenstein-esque death ray finale. Reportedly, when co-star,

Myrna Loy first read the screenplay cobbled together by Irene Kuhn (who never

worked in movies hereafter), Edgar Allan Woolf and John Willard, to cast her as

Fu Manchu’s slinky/kinky hedonistic daughter, Fah Lo See, her initial reaction

was to brand the material as ‘obscene’. None of this seemed to bother

Thalberg who charged ahead to make The Mask of Fu Manchu the undeniable

high point of Metro’s short-lived investment in horror.

As before,

Thalberg went slumming to Universal for the right talent to appear, getting

Boris Karloff fresh from his back-to-back triumphs as the monster in Frankenstein

and mute butler in The Old Dark House (1932). The Mask of Fu Manchu

ought to have been Charles Vidor’s directorial debut. Except Thalberg, after a

few weeks shoot, suddenly thought better than to let a novice take command of

one of the studio’s costlier experimental ventures; instead, handing the reigns

to Charles Brabin, already a veteran of 44 features. The Mask of Fu Manchu

went before the cameras with no ‘officially’ completed script. Karloff, whose

initial request to see a working screenplay was met with modest chuckles, was

soon to discover himself embroiled in one of Metro’s most chaotic productions. Daily,

Karloff was given ‘new’ pages to memorize on the fly, often to test his

patience as well as his memory, only to be met hours later by some underling,

presenting him with even more revisions to insert into his performance. Even as

cameras continued to roll, producer Hunt Stromberg was rapidly at work, generating

incredible story ideas, some – like Fu Manchu’s command of a giant robot –

almost immediately thrown out, while others, or portions at least, getting

integrated into the living fabric of the Kuhn/Woolf/Willard narrative.

Karloff endured

nearly 2-hours of daily applications to be transformed into the Asian devil at

the hands of makeup artist, Cecil Holland. And although this was nothing to the

reported 5-hrs it took to make Karloff over as Frankenstein’s monster, or the rumored

7 ½ hrs. required to age Karloff as The Mummy (made immediately after The

Mask of Fu Manchu at Universal), Karloff became critical of Holland’s

efforts. Holland was no Bud Westmore. Meanwhile, Myrna Loy grumbled over the

studio’s expectations for Fah Lo See, whom Loy described as a “sadistic

nymphomaniac.” Perhaps, it was Karloff and Loy’s mutual scorn for the

material that brought them together in their rather pleasant passion to make

something of high art from the camp afforded their characters. In later years,

each star would regard the other as a total pro, with Karloff suggesting no one

but Loy could have brought even an ounce of dignity to the part of this

shameful harpy, while Loy praised Karloff as the consummate gentleman’s

gentleman, quite unlike the ruthless and vial specter he was asked to portray

on the screen.

Cribbing from an

age-old euphonism, that during the age of Greece, gods and goddesses disguised

themselves as mortals to roam the earth, while in Hollywood’s golden age of

glamor and affectation, mere mortals pretended at gods and goddesses by never

leaving the backlot at MGM; for good measure, the studio hedged its bets on The

Mask of Fu Manchu, stocking even bit parts with exceptionally fine talent: the

venerable Lewis Stone as Secret Service agent, Sir Denis Nayland Smith, sexpot Karen

Morley as Sheila Barton, whose father, Sir Lionel (Lawrence Grant) is the first

to fall prey to Fu Manchu, celebrated character actor, Jean Hersholt as fearful

Dr. Von Berg, and, as the butch and intrepid love interest, Terrance Granville,

Dartmouth square-jawed footballer, Charles Starrett – whose later career in

films was relegated to B-westerns at Columbia. MGM’s biggest all-star

extravaganza of 1932, Grand Hotel, validated the merit in stockpiling

top-tier mega-talent into one movie. Thalberg defied the ancient edict in

Hollywood that one star per picture was quite enough. Forever thereafter, Metro

set a glittery standard, forcing the other A-list studios to try and compete with

their all-star cavalcades. Having gambled much on The Mask of Fu Manchu,

the executive brain trust at MGM was to break into a collective cold sweat

after viewing Charles Vidor’s early dailies, fearing another financial fiasco

akin to Browning’s Freaks. Production

was shuttered, Vidor fired, and most – if not all – of his footage, scrapped as

Thalberg retooled with Brabin at the helm.

Yet, the studio’s

biggest concern had absolutely nothing to do with making of the picture.

Instead, L.B. Mayer and his cohorts pondered how to massage away the scandal

surrounding the ‘death/murder’ of producer, Paul Bern, who also happened to be

wed to one of their biggest stars – Jean Harlow. The particulars of Bern’s demise

remain a mystery to this day; found naked and dead in an upstairs’ bathroom,

from an apparent, self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head, leaving behind two

typed suicide notes as a cryptic apology. Mayer and studio publicist, Howard

Strickling were first to arrive on the scene, and hours before anyone bothered

to telephone the police. Bern’s death was then, almost immediately, restaged to

offset suspicions that Harlow herself was somehow involved. A few days later: the

shocking suicide of Bern’s first wife, Dorothy Mallett, judged mentally

unstable, but who may have also administered the fatal shot to Bern before

drowning herself. Given the sordid and sundry

methods of torture Karloff’s Fu Manchu would be inflicting on screen, Mayer was

concerned MGM’s reputation, especially on the heals of Freaks, and, the

Bern suicide, would infer to the public that sadists thrived at his ‘dream

factory’. So, managing the tabloids was good business, if only to mitigate the

impression MGM had somehow declined in its morals and chic good taste. It all

played into Mayer’s determination to realign the studio’s public image with a

more wholesome air, set apart from its otherwise imperious glamor.

At just a little

over an hour, The Mask of Fu Manchu moves like gangbusters through its

cartoonish plot. We are introduced to Sir Denis Nayland Smith who forewarns

Egyptologist Sir Lionel Barton of Fu Manchu’s fiendish plot to covet the death

mask and sword of Genghis Khan, thus to inflame Asian sentiment to annihilate

the white race. Barton is kidnapped by Fu Manchu’s agents while departing the

British Museum, and, brought to heel at Fu Manchu’s Gobi desert lair. The

enterprising Fu Manchu at first offers Barton a bribe, even his daughter, Fah

Lo See as Sir Lionel’s concubine. Refusing, Barton is then taken to the ‘torture

of the bell’ – held in place by restraints to succumb to its deafening knell

while Fu Manchu repeatedly demands to know the whereabouts of Sir Lionel’s

archeological dig. Meanwhile, Barton's

daughter, Sheila appeals to Nayland, thereafter, to accompany the expedition with

her fiancé, Terrence Granville and associates, Dr. Von Berg and McLeod (David

Torrence). Not long thereafter, McLeod is knifed by Fu Manchu’s acrobatic

henchman. Despite Terry's misgivings, Sheila convinces him to take these relics

to Fu Manchu without Smith's permission.

However, when Fu

Manchu tests the sword under an elaborate electrostatic charge, it is revealed

as a fake. Terry is stripped and whipped on Fah Lo See’s erotic command, and,

later injected with a mind-controlling serum to do Fu Manchu’s bidding. Meanwhile,

Barton's severed hand is delivered to Sheila. When Nayland tries to liberate

Terry, he is taken captive, tied to a cantilever dangling over a pit of live crocodiles.

A reprogrammed Terry is sent by Fu Manchu to collect Sheila and Von Berg, feigning

that Nayland has ordered them to deliver Khan’s mask and sword to Fu Manchu.

Sensing something is remiss, Sheila and Von Berg are taken hostage by Fu Manchu’s

minions. They plan to make a human sacrifice of Sheila and impale Von Berg in a

torture device. Now, Terry is prepped for a fatal dose of serum, presumably to

transform him into Fah Lo See’s permanent slave. Mercifully, Nayland manages a

daring escape. He saves Terry before the fatal dose of the serum can be

administered and liberates Von Berg from his torture device. Nayland then employs

Fu Manchu's death ray to annihilate his arch villain and the wild-eyed followers.

Sometime later, Sheila, Terry, Von Berg and Nayland embark on a clipper, bound

for England, with Smith tossing Khan’s sword overboard, thus preventing it from

falling into the hands of ‘another’ Fu Manchu.

The Mask of Fu

Manchu hit theaters on November 4, 1932 and, based on the popularity of the

novels, easily doubled its $338,000 budget in box office returns. Alas, its trials with the censors had only

just begun. While various boards across the states and in Europe made their own

indiscriminate cuts, as to what constituted racially offense, or at the very

least, ‘sensitive’ material, the picture’s popularity with the general public could

not be underestimated. Unfortunately, controversy hardly mellowed when MGM

elected to re-issue the picture as part of a triple bill. Appalled, the Japanese

American Citizens’ League sent the studio a letter, asking for its permanent removal

from MGM’s distribution catalog, citing Fu Manchu as “an ugly, evil

homosexual with five-inch fingernails, while his daughter is a sadistic sex

fiend.” Though MGM’s PR department did not directly respond, it kept The

Mask of Fu Manchu out of circulation for decades thereafter, even to bypass

it for a VHS home video release in the mid-1980’s. By then, various wholesale

cuts were baked into the original camera negative – presumably, discarded and

lost for all time. When The Mask of Fu Manchu finally arrived on DVD in

1992, it was the ‘slimmed down’ version with most of its ‘offensive’ dialogue shorn.

But now, arrives

the Warner Archive’s (WAC) new-to-Blu, derived from a curated original camera

negative housed at the BFI. Virtually all of the previously excised footage,

deemed incendiary to Asian culture, is back in for our consideration. Actually,

85% of this B&W image appears to have come from an excellent source,

sporting appropriate grain, exceptional tonality in its gray scale, and

gorgeous amounts of fine detail, truly to show off Tony Gaudio’s nightmarishly

conceived deep-focus cinematography and Cedric Gibbon’s sublime art direction

to its very best advantage. However, the one-time excised portions, more

recently reinstated, appear to have come from a print master several

generations removed from these pristine elements. When these inserts appear,

they suffer rather horrendously from a sudden loss of crispness, with blown-out

contrast to obliterate virtually all detail, as well as to amplify film grain into

a gritty mess. This makes the reinstatement of these previous cut portions utterly

transparent and, frankly, distracting. The 2.0 DTS mono audio is more consistent,

with no discernable distortions. Extras are limited to two vintage cartoon

shorts and an audio commentary by historian, Greg Mank, whose insights are

comprehensive and always enjoyable to observe.

Bottom line: The Mask of Fu Manchu is a rather morbid and truly

bone-chilling thriller, quite uncharacteristic of MGM’s vintage thirties’ output. Although Karloff later disowned this performance, he really had nothing to be ashamed of here. His ghoul is disturbingly evil. The Mask of Fu Manchu shares in the Metro’s verve for applying surface sheen, adhering to Mayer’s

edict, “Do it big. Do it well. And give it class.” But the picture is

decidedly a daring departure, and, occasionally, the disconnect with Metro’s

in-house style is bizarrely out of whack. While there are decided shortcomings

to this Blu-ray transfer, WAC has done its utmost to preserve The Mask of Fu

Manchu in a manner almost befitting the quality and efforts with

which it was originally created. Judge and buy accordingly.

FILM RATING (out

of 5 – 5 being the best)

3.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

1

Comments