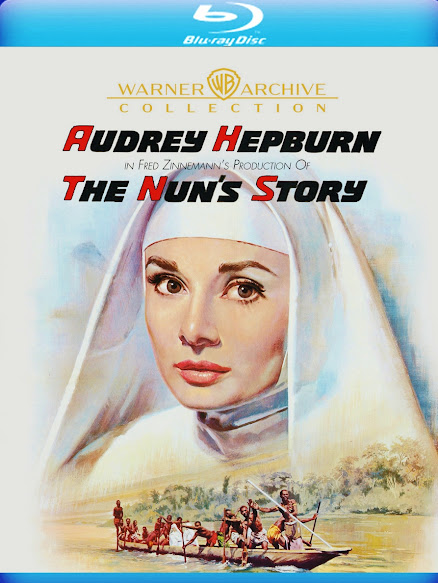

THE NUN'S STORY: Blu-ray (Warner Bros., 1959) Warner Archive

It’s been said,

where great power resides, equally rests grave risk for the abuse of it.

Perhaps, never a more indicative claim than when cast upon the Catholic church.

Based on Kathryn Hulme's shocking novel, director, Fred Zinnemann's The

Nun's Story (1959) is an unapologetic deconstruction of the structure and

strictures placed upon young noviciates as they commit their lives to God.

Robert Anderson's screenplay surrenders the filmic piety of devout Catholicism

(made warm-hearted in movies like 1944’s Oscar-winning, Going My Way and

its follow-up, 1945’s The Bells of St. Mary's) instead, to assign much

of this movie’s lengthy 152-minutes to a far more unflattering treatise on the

inward sacrifices and moral rigidity of the church in its fervent quest to

create ‘the perfect nun’. That, this story's heroine, Gabrielle Van der Mal

(Audrey Hepburn) is born of impeccable stock, morality and social background

above reproach - and thereby, seemingly ideally suited to her calling - yet, unable

to attain personal enlightenment via blind obedience - strikes a particularly

devastating chord. Evidently, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese agreed, and were none

too pleased with Hollywood’s ambitions to scrutinize their cloistered

teachings.

Our story opens

with Gabrielle leaving her idyllic family life to join the convent in

Rotterdam, Holland. It is Gabrielle's fervent desire the sisterhood will assign

her to missionary work in the Belgian Congo upon receiving her vows.

Gabrielle's father, Dr. Van der Mal (Dean Jagger) urges Gabrielle to reconsider

her chosen path. At home with him, she has the love, support and devotion of

two sisters, a brother, and, a fiancée. Still, Gabrielle is certain the nunnery

is her true calling. She is sequestered along with other hopefuls and put to

task under the most stringent conditions and house rules. A proper nun - so we

are told - can never look at herself in a mirror. She does not form

'attachments' (friendships) with fellow novices. She obeys without question any

and all requests from her superiors. She does not speak unless she is spoken to,

and, she resigns herself to forget every last fact from memory about her own

past. A little black diary is given to each noviciate into which she must daily

'accuse' herself in writing of each impure thought. The Holy Rule is supposed

to attain a sense of higher purpose, to help repress all sense of self and to

smite vanity in all its forms.

Rechristened

Sister Luke, Gabrielle invests herself with ardent purpose, yet oddly, with a

constant self-doubt her studies are being sabotaged by pride. Sister

Margharita, the Mistress of Postulants (Mildred Dunnock) is Gabrielle's

greatest proponent. It is through Sister Margharita's constant encouragement,

Gabrielle finds the strength to persevere, even as some of her cohort recognize

the life of a nun is not for them and begin to drop out. However, at the

hospital where Gabrielle is stationed to care for the sick, as well as train in

her medical duties, a noviciate accuses Gabrielle of being prideful in her

superior mastery of medicine. The accusation reaches the ears of Mother

Marcella (Ruth White) who all but demands Gabrielle deliberately fail her final

examination. However, it is essential Gabrielle pass the medical portion to be

considered for assignment in the Congo. Defying Mother Marcella, Gabrielle

comes in fourth from the top of her class during the oral medical examination.

As punishment, she is re-assigned to care for the criminally insane in a

sanitarium and is nearly murdered by one of its occupants who refers to herself

as the Archangel (Colleen Dewhurst).

Eventually,

Gabrielle does make it to the Congo, but here too her aspirations to care for

its native inhabitants are dashed by the Catholic Archdiocese when she is

instead assigned to the white hospital presided over by Dr. Fortunati (Peter

Finch); a no-nonsense surgeon who comes to greatly admire Gabrielle for her

medical prowess. Dr. Fortunati even goes so far as to conceal Gabrielle's bout

of tuberculosis from the church in order to heal her himself while keeping her

close at hand as his medical assistant. After the local Chaplain, Father Andre

(Stephen Murray) is injured in a bicycle accident, Gabrielle manages to reset

his crushed bones without Fortunati's aid and saves Father Andre's leg. This

noble deed earns Gabrielle the respect of the entire congregation - yet, she is

'punished' once again for her pride of workmanship by being recalled to convent

life in Rotterdam. Once home, Gabrielle learns her father has been mercilessly

gunned down with other refugees by the Nazi army. Realizing she cannot endure a

life of servitude where her innate skills as a medical nurse are undervalued,

Gabrielle declares she has decided to leave the nunnery once and for all. After

signing her declaration, she is quietly and rather unceremoniously cast out of

the convent, departing by a back door, presumably in disgrace, and, into a very

bleak and uncertain future.

Thus, ends The

Nun's Story on a shockingly ambiguous note. The movie is immeasurably

blessed by Audrey Hepburn's poignantly understated central performance. There

is real chemistry between Hepburn and Finch in their brief scenes together. In

hindsight, one sincerely wishes for more of these. To Hepburn’s credit, the

story - without much verbal interaction between Gabrielle or anyone else –

nevertheless, is compelling. Sister Luke’s struggles to attain enlightenment

beyond her own willful resolve become our own, as she navigates her way through

two life-altering decisions; the first, to become a nun, the second, to

surrender this vocation for an undetermined, and ostensibly daunting future

alone in the wide-wide world – and, one at war, no less.

One cannot

overstate the artistic pitfalls Zinnemann had to overcome to get The Nun’s

Story made; not the least, appeasement of the Catholic League of Decency. Robert

Anderson’s screenplay adheres faithfully to Hulme’s novel – omitting only one

major plot point from the novel (a mental patient’s assault on Sister Luke). But

the graver concern, at least as far as Jack Warner was concerned, was the

picture’s thinly veiled critique of the trials of an actual Belgian nun, Marie

Louise Habets. These could not be dismissed. As early as 1956, Warner and

Columbia both approached Hollywood’s self-governing censorship board to inquire

about the feasibility of making a picture while Hulme’s book was still in gallies.

Warner found much support in Jack Vizzard, then head of the Production Code. But

what really concerned Vizzard, as well as Warner, had more to do with the book’s

publication shortly thereafter. While receiving wide critical acclaim, The

Nun’s Story also proved divisive with Catholic readers and their

archdiocese, the latter believing Hulme’s novel mispresented the plight of

potential postulants as slightly grotesque and monumentally discouraging. Warner

eventually outbid Columbia to produce it, forewarned of the movie’s potential

to alienate a vast sector of the public. In Hollywood, The Nun’s Story

drew hushed reticence from many who refused to partake of the exercise.

Mercifully, the project gained considerable traction after Audrey Hepburn

expressed her desire to appear in it.

On August 14,

1957, the studio submitted Anderson’s first draft to the Production Code Office,

in conference with the National Legion of Decency’s Monsignor John Devlin. While Devlin concurred, the script was “substantially

acceptable”, he also believed it stressed all of the rigors and none of the

joys of entering religious life. As

such, Devlin suggested an effort be made to show that Hepburn’s Gabrielle had

entered her calling under a false ideal. The blame for her failure was therefore

hers alone to bear, not through any fault of the Catholic church. Alas, the

Roman Catholic church in Belgium, having already condemned Hulme’s novel as

injurious to those in religious vocations, now turned their mistrust against

the movie, refusing Zinnemann any allowance to shoot on location. Meanwhile, Vizzard

tapped Leo Joseph Suenens, auxiliary Bishop of Mechelen to renounce his

objections, using Father Leo Lunders as an interventionist. Lunder resisted

Warner’s initial desire to cast either Montgomery Clift or Raf Vallone in the

pivotal role of Doctor Fortunati. At this juncture, the project picked up

another ally in Harold C. Gardiner who, together with Lunders, hired as the

picture’s ecclesiastical advisor, and Vizzard, won over Monsignor Suenens seal

of approval. Alas, nothing further could proceed without the approval of Mother

General of the Sisters of Charity of Jesus and Mary in Ghent. The Sisters provided

the studio with its own screenplay, taken to heart, if not imperative, with

several of their ideas incorporated into Anderson’s screenplay to grease the wheels.

Interestingly, there

were no objections to the largely non-denominational cast invested in telling this

very Catholic story: Fred Zinnemann - Jewish; Audrey Hepburn and Edith

Evans - Christian Scientists, Robert Anderson - a Protestant, and, Peggy

Ashcroft – agnostic. Instead, the production was given access to observe real

religious ceremonies and traditions, with Hepburn and her costars invested in a

prolonged stay at Assumptionist Convents in Paris. Zinnemann also stayed in

close contact with the novel’s author, Kathryn Hulme, whom Hepburn met in

consultation, as well as Marie Louise Habets, on whom Hulme’s fictional

counterpart was based. Hepburn and Habets bonded over their common Belgian

roots and hardships endured during the Second World War. And long after the

picture’s premiere, Habets would reenter Hepburn’s life again, nursing the

actress back to health after her riding accident on the set of The

Unforgiven (1960).

Zinnemann, a

very ‘hands on’ director, held tight to Anderson, constantly consulting and

collaborating on the finessing of his screenplay, as well as remaining laser

focused on achieving the best performances from all of his principal cast. Discovering

she was pregnant at the outset of the production, co-star, Patricia Bosworth underwent

an underground abortion, resulting in severe complications that delayed

production for several weeks. In the

meantime, Zinnemann hired Colleen Dewhurst, in her screen debut as Archangel

Gabriel, and, Renée – his wife, as an assistant to Edith Evans (cast as Mother Superior). Also appearing, such Hollywood stalwarts as

Dean Jagger (Dr. Hubert Van Der Mal), Mildred Dunnock (Sister Margharita), Beatrice

Straight (Mother Christophe), Barbara O'Neil (Mother Didyma), and Brits, Lionel

Jeffries (Dr. Goovaerts), and Niall MacGinnis (Father Vermeuhlen). Along the

way, Zinnemann’s ambitions for the picture morphed – scrapping plans for

cinematographer, Franz Planer to shoot only the African scenes in color,

counterbalanced by the relative drabness of the European sequences, initially

planned for B&W. For technical reasons, Zinnemann also had to abandon a

sequence meant to appear near the end of the picture in which three men are

caught in quicksand and rapidly rising water. As the Catholic diocese in

Belgium still would not allow Zinnemann access to their churches, the ‘Belgian’

portions were lensed in Rome at Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia and

Cinecittà on sets designed by Alexandre Trauner with extras culled from Rome’s

Opera company.

Shot mostly on

location in the Belgian Congo, The Nun’s Story was wildly popular with

audiences, not the least, as the latest feature starring the luminous, Audrey

Hepburn. On a budge of only $3.5 million, it grossed $12.8 in domestic receipts

alone, making it Hepburn’s most successful movie to date. Hepburn would garner

one of the picture’s eight Oscar nominations, as Best Actress, losing out to

Simone Signoret for Room at the Top. Critical plaudits ranged from ‘amazing’

to ‘tasteful.’ Even the National Legion of Decency was impressed, classifying The

Nun’s Story as ‘morally unobjectionable for adults and adolescents’, though

with the backhanded footnote, “If the film fails to capture the full meaning

of religious life in terms of its spiritual joy and all-pervading charity, this

must be attributed to the inherent limitations of a visual art.” Nominated

for 8 Academy Awards, The Nun’s Story was virtually overlooked in 1959,

the year William Wyler’s Ben-Hur cleaned up at the podium. Nevertheless,

Zinnemann received ‘best director’ honors from the New York Film Critics, as

well as the National Board of Review.

For decades, home

video releases of The Nun’s Story have remained the bane of the

industry, owing to the picture being shot on Eastman 5248 acetate-based film

stock, a micro-fine grain, yielding remarkable clarity and ease of use in both indoor

and outdoor photography. Initially, Eastman’s single layer technology, with its

light sensitive emulsions, was regarded as an advantage to the more cumbersome,

if time-honored 3-strip Technicolor process. Ironically, processing the film

stock reduced the density of its emulsion significantly – the net result, over

time, no viable prints could be struck from the original camera negative. And

if no separation masters were made at the time of production, an entire movie

could well be lost forever. Worse, and, all-too-soon, Eastman 5248 became

rather notorious for its color instability and proneness to extreme color

fading.

The Warner

Archive’s new-to-Blu of The Nun’s Story is therefore cause for

celebration, as Warner's MPI remastering facility have managed a minor miracle,

lifting an incredible amount of color fidelity off the film’s original camera

negative, resurrecting the luminescence of its dye transfer, originally

processed at London’s Technicolor facility. Point blank: The Nun’s Story

has never looked more beautiful on any home video format, herein, sporting exquisitely

accurate film grain, stunningly handsome hues and superb contrast. Flesh tones

that previously registered as a garishly dull orange are now returned to their

creamy soft pink alure. The green foliage, always to appear muddy brown, now

burst forth with a luxuriant vibrancy. It’s a revelation to revisit The Nun’s

Story in hi-def, and kudos must be paid to those responsible for this

reincarnation. The 2.0 DTS mono audio has been finessed and is the perfect

compliment to these incredible visuals. Again, we get short-shrift in the

extras. No audio commentary or ‘making of’ or even a restoration comparison

reel. For shame. Oh, well. Can’t be too harsh, when WAC has spent its money

correctly on delivering Zinnemann’s classic from the brink of color implosion,

and, in an exemplary transfer that will surely NOT disappoint. Viewing The

Nun’s Story on Blu is like seeing it for the very first time – and,

arguably, on its initial theatrical release in 1959. Very highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out

of 5 - 5 being the best)

4.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

5+

EXTRAS

0

Comments