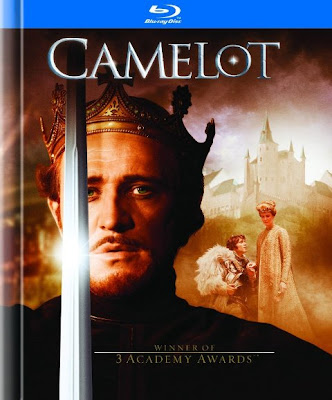

CAMELOT: Blu-ray (WB 1967) Warner Home Video

The 1960s were

particularly unkind to the American movie musical. The studio system – that had

so effortlessly assembled all the necessary creative talents to meet the

demands of making a big budget musical – was gone. Under their creative aegis

movie musicals had artistically profited from a distinctive ‘in house’ style.

It was virtually impossible to confuse a musical made at MGM with one developed

over at Fox, per say, or anywhere else for that matter. But eventually

audiences began to tire of the formulaic ‘boy

meets girl’ scenarios. If the songs were winners a musical might still pull

in the audience. But if they were simply mediocre tastes had already begun to

shift, substantially enough to stay away and simply catch one’s favorite

musical talent at home on variety shows like Ed Sullivan or The Tonight

Show.

By the

mid-1960s there didn’t seem to be much point to the big and splashy movie

musical any more – despite its sporadic successes throughout the decade. Lest

we forget this was still the decade where Robert Wise’s The Sound of Music had managed to undue much of the financial damage Fox incurred on Cleopatra.

Disney had had his greatest success in live action with Mary Poppins, while West

Side Story and My Fair Lady had

all but dominated the Academy Awards in their respective years. But these were

exceptions to the rule. Nevertheless, musicals remained in vogue in Hollywood,

even as late as 1967, the year Joshua Logan undertook to bring Lerner and Lowe’s

Camelot to the big screen.

Jack Warner

was still in charge of Warner Brother but his movie empire was in a state of

financial retrenchment. Although Warner still maintained an extensive

storehouse of props and costumes, as well as pride in a series of back lots –

at least for a time, the writing was already scrawled on those walls to have a

date with the wrecking ball. Worse, the creative personnel (choreographers,

singing coaches, stage directors, et al) necessary to create the musical had

since decamped – or, more to the point – been quietly asked to leave the premises

as soon as their iron clad contracts elapsed. Cost cutting was a necessity in

Hollywood throughout the 1960s, though arguably few heeded it when push came to

shove, because an even more queer mentality had begun to permeate the executive

logic. To combat TV, movies had to be landmark productions. As far as Hollywood

was concerned ‘bigger was definitely

better’. Too much of a good thing was still never enough. This ironclad

edict was further exacerbated by a glaring reality that studios blindly chose

to ignore; profits were at an all-time low even as production costs continued

to skyrocket through the roof. With so much upheaval and change buffeting the industry

it remains a small wonder that anything of quality was being made.

Despite these

impediments Hollywood valiantly trudged on; usually to its own detriment. In

retrospect, Camelot seems to have

suffered greatly from this acute elephantitis. Designed as a ‘road show’,

complete with intermission and fanfare the resulting 179 minute film became as

overblown as it was overproduced; misguidedly miscast with actors rather than

singers to carry on in the grand tradition of the stage show. On Broadway, with

its impressionist backdrops and subtle interplay of stagecraft lighting, Alan

Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe score had possessed an ethereal quality.

Regrettably, on film these melodies became grounded in realism – gaudy indoor

sets that completely robbed this familiar Arthurian fantasy of its more magical

properties.

Unlike the

stage show, the film’s central plot is told as a giant flashback with

world-weary King Arthur (Richard Harris) first glimpsed as the steely blue-gray

of dawn creeps over the horizon. This is Arthur in the twilight of his former

glory. In fact the man has only hours to live. He is preparing for battle against

Sir Lancelot (Franco Nero); once his most trusted, noblest knight of the round

table. Arthur’s piteous reflections of happier times lead him to a faithful

plea for guidance from his childhood mentor, the sorcerer Merlin (Laurence Naismith),

whose naive advice is to simply think back. Obeying Merlin’s command, Arthur

recalls his first chance meeting with his now estranged wife, Guinevere

(Vanessa Redgrave). Betrothed to Arthur, Guinevere flees into a mysterious

forest on the eve of their wedding. She finds Arthur just as forlorn by the

prospect of marrying someone he has never met. Without knowing either’s

identity the two become acquainted and Guinevere realizes that her lord and

master is not only a patient man, but a benevolent ruler who desires to unite

England’s disjointed provinces under one kingdom to be governed justly by

Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. How very democratic indeed!

News of

Arthur’s passionate quest to restructure England reaches the shores of France

where the self-righteous Lancelot thinks it a splendid idea; one ideally suited

to his own superior virtues. Without cause – or invitation, for that matter –

Lancelot makes journey to Camelot. The knight’s prowess with a sword impresses

Arthur and the two become immediate friends. But Lancelot’s robust ego is initially

a turn off to Guinevere who goads three of the Round Table’s most proficient

protectors – Sir Lionel (Gary Marshal), Sir Sagramore (Peter Bromilow) and Sir

Dinadan (Anthony Rogers) – to challenge him to a joust. Lancelot easily

dispenses with them. But his victories come at a terrible price. Although sworn

to celibacy, Lancelot finds that he has begun to harbor a deep-seeded passion

for his queen. Worse, she has fallen madly in love with him.

Arthur turns a

blind eye to his wife’s illicit romance, especially after his own illegitimate

son Mordred (David Hemmings) arrives in search of his father’s acceptance.

Unwilling to acknowledge the boy, or allow him fellowship to the Round Table,

Arthur is encouraged to go on a hunting trip by Mordred who knows that

Guinevere will be unable to resist Lancelot in her husband’s absence. That

evening, the lovers reunite. Only this time Mordred has placed several knights

in the vicinity of Lancelot’s bedchamber to catch them in the act. Lancelot

escapes persecution for his ‘crime against the state’. But Guinevere is taken

prisoner and sentenced to be burned at the stake. At the last possible moment

Lancelot reappears and rescues his beloved, much to Arthur’s relief.

Regrettably, Arthur is bound by the law to persecute the pair. The flashback

ends. Arthur is unexpectedly visited by Lancelot and Guinevere who has

renounced her lover to become a nun instead. It makes no difference, however. Arthur

must go to war. As the trumpets sound Arthur meets a peasant boy, Tom of

Warwick (Gary Marsh) who declares his allegiance to the high ideals of Arthur’s

Camelot. Knowing that he will likely die in battle, Arthur knights Tom; then

commands the boy to wait behind the battle lines so that he will be able to

tell future generations about the legacy of Camelot.

As pure

stagecraft co-starring Richard Burton and Julie Andrews, Camelot proved a magical – though hardly perfect – theatre-going

experience. The film, regrettably, suffers in their absence from too much

inspiration and not quite enough perspiration put forth in the performances by

the principle cast. Although Vanessa Redgrave is winsome enough as Guinevere,

her singing voice is anemic and rather coyly perverse. Worse, Redgrave seems to

be playing the queen as an enterprising female from the start, rather than the

ever loyal companion who becomes inadvertently corrupted by lust.

Richard Harris

is an actor of considerable merit. But musicals are not his forte and he proves

it with too many mannerisms that make his Arthur a weak-kneed martinet and

slave to the latest fashion. On the flipside is Franco Nero; in very fine voice

indeed, but who does not believe anything his character says or does. These

woeful misfires deprive Camelot of

its fragile emotional center. As such the film exaggerates, instead of

rectifying the stage show’s awkward imperfections. If the rest had come

together under Joshua Logan’s direction at least something might have been

salvageable. But Camelot misses its

mark on almost every level. Logan’s heavy-handed direction makes the plot drag.

Richard H. Kline’s cinematography is pedestrian at best with excruciatingly

long static shots designed to show off John Truscott’s production design, but

that anchor the visuals in a sort of stage bound limbo. Truscott’s sets are

also problematic; rather drab and too faithful to that period to be fully

appreciated as the fanciful locations for a medieval fantasy. The costumes are

infrequently bizarre, including one dress worn by Redgrave sewn with pumpkin

seeds. But everything tends to run together; the courtiers and their ladies

fair reduced to an indistinguishable rabble wearing more of the same. What we

are left with, then, is Lerner and Loewe’s score – given full bodied

orchestrations by Alfred Newman and Ken Darby that all but drown out the thin

vocals. In the final analysis, the genuine mystery of Camelot the movie is how a studio as rife with insight on the making

of iconic 60s musicals as My Fair Lady

and The Music Man could have so

completely mismanaged that legacy with this abysmal contribution.

I have long

been perplexed by Warner Home Video’s decision making process to green light

weighty clunkers like Camelot for

Blu-ray before more worthy contenders like Yankee

Doodle Dandy, Gypsy or even Calamity

Jane. With the old MGM, RKO and Selznick libraries currently under their

umbrella, there is so much good stuff to choose from that a chestnut like Camelot really doesn’t rate being

pushed to the front of the line. But I digress, because there’s really nothing

to complain about with Camelot as a

Blu-ray. Warner has gone back to the drawing board to produce a spectacular

looking hi-def transfer that is absent of the horrible aliasing and edge

effects that plagued their DVD release from 1997. The image is dark and softly focused

– as it should be. Colors pop. Fine detail and grain are faithfully reproduced.

The audio has been repurposed into a lush and lovely 5.1 DTS that flows and

glows with sonic aplomb.

Extras are a

tad disappointing. Stephen Farber gives a most comprehensive audio commentary

full of insightful information. There’s also a newly produced featurette ‘Falling

Kingdoms’ that parallels the steady decline of Jack Warner’s movie

empire with the fictional realm of Arthur’s kingdom. We also get the vintage

‘premiere’ footage and a slew of trailers that were also included in the DVD

release; plus a CD sampler. Oh, for heaven sakes; just give us the whole damn

score and be done with it! What is

missing from this Blu-ray is the isolated 5.1 Dolby Digital score that came

with the DVD – and such a shame too.

FILM RATING (out of 5 - 5 being the best)

2.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

2.5

Comments