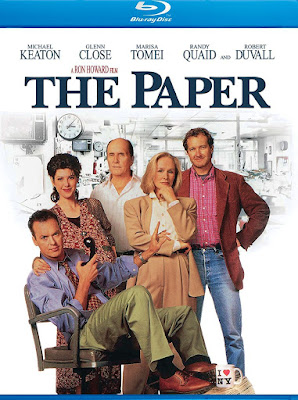

THE PAPER: Blu-ray (Universal/Imagine, 1994) Universal Home Video

By my assessment Ron Howard has never made a movie to manipulate his audience for the sake of a

good pop-u-tainment. Indeed, Howard does not make ‘puff pastry’ from popular culture; nor does he get mired in the

particulars, though concentrated as he can, and usually is, on extolling the

details of everyday life. Instead, Howard illustrates a startling command of

complex issues, clearly seeing through to the heart and soul of each character

populating his movie’s milieu. I suppose this alone is the hallmark of a truly

gifted cinema story-teller. And there are far too few working in Hollywood

today. So, let us set aside the Opie/Ritchie Cunningham references that,

particularly at the start of his career, seemed rather condescendingly to

suggest another ‘failed’ TV star was making a clumsy segue into some fairly

disposable feature films. And while we are on this subject, I respectfully doff

my cap to the likes of Penny (Laverne) Marshall and Rob (‘meathead’) Reiner. It

seems 70’s sit-com training came in very handy for this trifecta of

story-telling geniuses.

But back to Ron

Howard, whose directorial career has been peppered in mega hits of varying

creative merit. Virtually none are a total waste of time. But when he hits the

bull seye, it’s with the telescopic range of sure-fire box office. Hence, the

work is always rife for rediscovery and future appreciation. I confess: I missed The Paper (1994) on its theatrical release; the idea of ‘another’ valediction of journalistic

integrity run amok holding little interest for me then. Lest we forget, 1994

was the year of Pulp Fiction, and, Four Weddings and a Funeral; also, True Lies, The Shawshank Redemption, Forrest

Gump, The Lion King, Little Women, Leon: The Professional, Legends

of the Fall, Clear and Present

Danger, Maverick, Speed, Reality Bites, I Love

Trouble, and, The Santa Clause…to

name but a handful; all of which I did

see in a theater. The Paper ought to

have appealed to me too. I adore Glenn Close and believe Robert Duvall to be

one of the greatest actors of our time. In hindsight, I think it was the ‘coming

attractions’ trailer that killed my interest in The Paper; misguidedly zeroing in on the drama while virtually

dumping all of the screwball elements Howard had toiled so craftily to

counterbalance, yet queerly augment these histrionics with zap-dramatic

intensity and razor-biting irony feathered in for good measure. But no, the

trailer for The Paper played like a wafer-thin

and somewhat cartoony attempt at melodrama at best, charting the rise and fall

of forgettable bitchy, socially-frustrated outcasts on the verge of plucking

each other’s eyes out or suffering one collective nervous breakdown. The

curiosity is, in many ways, The Paper

still fits this descriptor to a tee with one crucial distinction.

It is a far more

engrossing and enveloping critique of the newspaper biz than virtually anyone,

apart from a handful of critics of their day, had given it credit. Billing The Paper as a ‘dramedy’ is like calling the Hoover Dam a nice little wall that

holds some water. In spots, The Paper

is deliciously funny and cynically dark; Howard, able to take incongruent

narrative elements and weave his master stroke as unapologetic and eviscerating

as a street fight between two junkyard dogs. Top cast is Michael Keaton as

Henry Hackett – as his moniker suggests, part mild-mannered every guy/part-con

(or ‘hack’) editor of The New York Sun; a rag tabloid teetering on the brink of

extinction. Keaton infuses his role with a sort of arresting, devilish charm.

He is fairly disreputable: stealing

story ideas right off the desk of Paul Bladden (Spalding Grey); rival editor at

The New York Sentinel (who has just offered him a cushy job, no less),

repeatedly standing up his very pregnant and emotionally fragile wife, Martha

(Marisa Tomei), and, engaging his managing editor, Alicia Clark (Glenn Close)

in a knock-down/drag-out fist fight during the picture’s climax.

There is nothing

about Keaton’s Hackett to endear him to his colleagues or the audience for that

matter. And yet, Keaton wins us over, partly by applying a quirky/gutsy and

slightly goofy charisma he has always possessed in spades, able to compensate

for his physical shortcomings as a leading man (he’s no George Clooney). Seemingly

without effort, Keaton can pull off the proverbial ‘rabbit from the magician’s

hat’ trick any time he wants to make us fall in love with such despicable

behavior. It works, time and again;

Hackett, the lynch pin in a very potent grenade of opportunities; either, to

save the day or screw things far beyond the point of no return. Ingeniously,

Ron Howard allows his movie to sail clear over this narrative precipice, and

then, as miraculously, make us believe his vessel has been tethered all along; everything

pulled back into perspective, both for his oily protagonist and the audience. Keaton is, of course, flanked on all sides by

some very heavy hitters. Apart from Robert Duvall (as The Sun’s caustic and

cancer-stricken editor-in-chief, Bernie White), and, Glenn Close’s beady-eyed

bitch in heels, we get Randy Quaid as reporter, Michael McDougal, an accident

waiting to happen; Jason Robards (The Sun’s shifty boy’s club owner, Graham

Keighley), Jason Alexander (as disgraced Parking Commissioner, Marion Sandusky);

finally, Jill Hennessy and Lynne Thigpen (both underused, but welcomed

nonetheless) as White’s estranged/emotionally wounded daughter, Deanna and

Hackett’s pert and ever-devoted secretary, Janet respectively.

We also have to

tip our hats to the bit players; ‘real

cards’, every last one – whether Roma Maffia’s sassy Carmen, Geoffrey

Owens’ quirky Lou, Clint Howard’s Ray Blaisch, Bruce Altman’s philandering

Carl, Jack McGee’s sheepish Wilder, or Edward Hibbert’s Jerry - each integral

to the flavor of the piece without given very much to do, The Paper’s cast alone (most glimpsed in cameo) has it pegged for

greatness. Better still, Howard has not rested on their laurels to carry the

load – only, for inspiration - already

investing every second of The Paper

in a sort of frenetic verisimilitude and decided verve for the newspaper biz;

thanks, in part to the sure-footed – occasionally ribald (and R-rated) –

writing style of David and Stephen Koepp. One of the crudest/funniest lines I

think I have ever heard in the movies – period – gets uttered by Duvall’s

pugnacious pit bull; informed by fellow coworker, Phil (Jack Kehoe) his

excessive cigar smoke has resulted in his own urine testing positive for

nicotine, Bernie bluntly tells Phil “then

keep your dick out of my ash tray!”

In retrospect, The Paper shares its most transparent

influence with Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s ground-breaking stagecraft, The Front Page (to be made as a movie

under its own title in 1931 and 1974, and, in the interim between, as perhaps

its greatest incarnation, His Girl

Friday, 1940). Howard here is also gleaning inspiration from his vast

appreciation of classic films of the 1930’s and 40’s, oft-set in the

behind-the-scenes world of cutthroat journalism. Indeed, the Koepps came to

their writing epiphany from this well-versed background; Stephen, as senior

editor at Time magazine, collaborating with brother, David – then, riding the

groundswell of instant fame for having adapted Jurassic Park (1993). Together, they conspired on a project

entitled, ‘A Day in the Life of a Paper’.

Likely owing to David’s success, Universal

Pictures happily greenlit this project. Ironically, and unknowing of the

Koepp’s efforts, director, Ron Howard – in good standing with Uni’s Imagine

Entertainment division – simultaneously expressed interest in doing a movie

about the behind-the-scenes chaos of running a newspaper. In an industry where

everyone knows everyone, Steven Spielberg pointed Howard to David Koepp. Initially,

Koepp and Howard met at something of a cross purpose; Howard, hoping to pitch

his own ideas, and Koepp, using the opportunity to praise Howard’s Parenthood (1989) instead. At some

point, Koepp’s flattery paid off; Howard, inquiring about his ‘next’ project

and, with pricked ears, quickly to learn it was exactly his kind of picture to

make. “I liked the fact that it dealt

with the behind-the-scenes of headlines,” Howard would later admit, “But I also connected with the characters…desperately

trying to find balance in their personal lives…”

Having agreed to

work together, Howard began his research with trips to both The New York Post

and Daily News; each to provide inspiration for the fictional ‘Sentinel’ and

‘Sun’ in the picture. But Howard’s real spark of brilliance was to have the

Koepps change the gender of the managing editor, from ‘Alan Clark’ in their

original draft, to ‘Alicia Clark’ in the final edit, without altering a single

line of dialogue. As David Koepp would later reason, “Anything else would be trying to figure out, ‘How would a woman in

power behave?’ And it shouldn't be about that. It should be about how a person

in power behaves, and since that behavior is judged one way when it's a man,

why should it be judged differently if it's a woman?” In the meantime, Howard

engaged New York’s top newspapermen, including former Post editor, Pete Hamill

and columnists, Jimmy Breslin and Mike McAlary (the latter, rumored as

inspiration for Randy Quaid), who informed the director of a trick readily exploited

to make their deadlines; using a police light to bypass traffic jams. Believing

those working for tabloids shared in a sort of sheepish embarrassment, Howard

was to have his eyes opened wide when virtually all of his interviewees

confessed to ‘enjoying’ their particular brand of headline-grabbing shlock. In Daily

News’ metro editor Richie Esposito, as example, Howard unearthed the embodiment

of Henry Hackett; a ‘rumpled, mid-30’s overworked, but very articulate bundle

of energy.

The Paper opens on the inner workings of an alarm clock and a

radio broadcast encouraging its listeners to ‘stay tuned’ because “your whole world can change in 24 hours.”

Indeed, the rest of The Paper’s tautly-written

112 min. will bear out the truth in this statement as two unsuspecting black

youth (Vincent D'Arbouze and Michael Michael), departing a diner after midnight,

accidentally stumble upon a crime scene: two white businessmen, brutally slain

– gangland style – in their parked car. Fleeing the scene after being

discovered by a passerby, the boys are apprehended and charged with homicide.

Meanwhile, across town, New York Sun editor Henry Hackett is stirring next to

his very pregnant wife, Martha. She is disgusted to find him still fully

clothed, lying next to her. Indeed, Henry’s priorities are severely screwed up.

What can we tell you? He is a news hound through and through; the front page

more important than the real news going on right before his eyes. Martha is

counting on Henry to land a new and better-paying position at rival

publication, The Sentinel. She sternly encourages Henry not to screw this one

up. They have lives to live, bills to pay, and a new mouth to feed on its way.

Henry feigns

understanding. Actually, he is already sorely distracted by the news of the

day; The Sun missed out on covering these murders, substituted with yet another

front-page devoted to the more recent screw-ups afflicting New York’s traffic

authority. The brunt of this piece is an on-going humiliation of the Parking

Commissioner, Marion Sandusky, ruthlessly pursued by the Sun’s reporter,

Michael McDougal. In the back of Henry’s

mind, he can clearly recognize his own obsessive workaholism fast leading him

down a similar path as his editor-in-chief, Bernie White. The curmudgeonly boss

is estranged from his adult daughter, Deanne because he always put the work

ahead of his family. But now, Bernie has been given his wake-up call; his

prostate, the size of a bagel, is cancer already spread to other parts of his

body.

At work, Henry

is acutely aware the balance of power is shifting; Bernie – as irritable as

ever, begrudgingly forced to side with The Sun’s owner, Graham Keighley (Jason

Robards), who has appointed Alicia Clark to oversee the necessary cutbacks, hopefully

to keep everyone afloat. Henry and Alicia are a toxic mix; his glib disgust

counteracted by her viciousness, though in fact, control tactics necessary to

keep The Sun’s unwieldy core of fly-by-the-seat-of-their-pants reporters from

completely wrecking these budgetary constraints. On the home front, Henry’s

wife, Martha is desperate for him to land a job with The New York Sentinel; presumably,

the Cartier of his industry. Its managing editor, Paul Bladden is all set to

give Henry the job. Whatever else he may be, Henry has proven himself one hell

of a newspaper man. That is, until he rather shamelessly swipes some crucial

information about the Williamsburg arrests right off Bladden’s desk during a

momentary lull in the interview. Discovering this theft too late, Bladden rescinds

his offer of employment. It’s probably just as well. Henry really had no

interest in making the cardigan sweater and suspender sect his penultimate

career move, despite the fact it would be better for his family.

Nearly nine

months pregnant with their first child, Martha’s behavior is…well…typical of a

woman with raging hormonal imbalances. Once a reporter for The Sun, Martha

genuinely misses the work: her days now spent binge-watching forgettable TV and

eating everything in sight. To assuage her guilty feelings of inadequacy,

Martha meets up with a close friend, Lisa (Siobhan Fallon) for lunch. Alas,

instead of quelling her fears, Lisa amplifies them by casually, and rather

cruelly pointing out all the reasons a child will utterly wreck Martha’s

chances of ever being a reporter again. Perhaps to prove Lisa wrong, Martha

undertakes to do some groundwork on the Williamsburg murders. What she discovers

is the murdered businessmen were actually caught dipping their hands in the

till of a business fronted by a prominent Mafia crime family. Hence, the likelihood

these guys were killed as part of a gangland-styled cover-up is far more

plausible than pinning the crime on a pair of black youth walking down the

street. Martha arranges for a nice quiet dinner at an upscale restaurant with

Henry’s parents, Howard (William Prince) and Sarah (Augusta Dabney). Alas, this

too Henry manages to ruin, arriving late, then suffering a panic attack while

listening to a child’s temper tantrum at nearby table. Actually, Henry’s mind

is not on dinner at all. Because several hours earlier he sent cub photographer,

Robin (Amelia Campbell) – practically a newsie virgin – to get a crucial picture

of the indicted brothers being hauled off to jail. Robin’s inexperience may

have resulted in Henry losing out on the biggest scoop of his career and he

knows it.

Mercifully, after

developing the proofs, Robin discovers the perfect shot to headline tomorrow’s

daily edition. Ditching Martha and his folks, Henry gets Michael to give him a

lift to the local precinct where he convinces one of his police informants,

Richie (Mike Sheehan) to confide the Williamsburg boys are being held not even

on circumstantial evidence. The police need a scapegoat. These boys are it.

Armed with this ‘anonymous tip off’ Henry and Michael hightail it to The Sun to

stop the presses. Meanwhile, Bernie has arrived at his favorite watering hole, destined

to have a philosophical/booze-induced conversation with the disgraced Sandusky,

neither aware of the other’s identity. On the other end of town, Alicia attends

a newspaper gala at Radio City, self-assured she can leverage her clout with

Graham to go over Bernie’s head for a raise. The ruse fails; Graham, calling

her bluff and further informing Alicia when her contract is up in eighteen

months she is free to field more lucrative offers elsewhere. Spurned and out

for blood, Alicia leave the party and heads back to The Sun, shocked to

discover Henry rewriting tomorrow’s headline as an exoneration of the Williamsburg

boys, even though the paper has already gone to press.

Vetoing his

authority, Alicia and Henry get into a ruthless brawl that ends with Henry

bloodying her nose and Alicia firing him. She orders the press operator to

continue without the new headline. Alicia, Henry and Michael winds up at the

same bar; Henry, desperate to appeal to Bernie to stop the presses. Henry tells

Alicia, despite The Sun’s notoriety for publishing ‘silly’ tabloid stories that

sacrifice integrity for sensationalism hers is the first headline to have

deliberately known better and still published ‘a lie’. Having suffered an acute

attack of conscience, Alicia hurries to the phone booth at the back of the bar

to stop the presses. Regrettably, at precisely this moment, Sandusky recognizes

Michael from across the room; unleashing his full wrath in a rather pathetic

drunken brawl. This ends badly when Sandusky manages to gain control of the

pistol Michael carries for protection; Sandusky, firing a shot that whizzes

past Michael’s head, but penetrates the phone booth. The bullet strikes Alicia;

a superficial wound in the calf, it nevertheless sends her into shock.

Across town,

Martha, again patiently waiting for Henry to come home, but this time

contemplating leaving him for good, suddenly begins to hemorrhage. Her

emergency phone call for help comes just as Henry is arriving home. The couple

are reunited in the belief they may lose their unborn child and each other; the

paramedics rushing Martha into emergency C-section surgery. On another gurney,

Alicia makes repeated demands to use the telephone. Refusing to sign her

release so the surgeon can operate on her leg, Alicia’s wish is granted and she

orders The Sun to run with Henry’s story on the front page. As dawn begins to

crest, Henry is informed Martha and their newly born son have survived this

ordeal. Henry glances adoringly at his boy lying in an incubator, entering

Martha’s room to beg for her forgiveness. They share some tearful kisses and

Henry learns The Sun’s early morning edition has run his ‘front page’ story. We

conclude with the local radio station proclaiming this latest bulletin, adding “…because your whole world can change in twenty-four

hours!” And indeed, for Henry Hackett, it most certainly has.

The Paper typifies the Benzedrine-driven megalomania that is today’s journalism. Using the

analogy of birth to illustrate the process by which tomorrow’s headlines are

given life today, director Ron Howard puts his audience through the paces of this

wild-eyed/wild ride, teeming in furious temperaments and ruthless conniving.

Howard’s best movies are ensemble-driven; his motley crew of eager beavers,

brewing their disparate temperaments, raging egos and dubious moral ethics into

quicksilver intrigues of a dysfunctional ‘family unit’. Henry Hackett has printer’s

ink coursing through his veins. He lives, breathes, eats and sleeps The Sun;

the real world only worth its weight as a juicy headline. Too many reviews suggest

Ron Howard’s finale is too ‘schmaltzy’ for what precedes it. Respectfully, I

disagree. As an actor, Howard’s métier was arguably television; a medium that

works best when it neatly ties its loose narratives threads together in under

an hour with a sort of ‘stay tuned’ approach to next week’s story-telling.

While one can debate how well this approach functions for the expanded 2-hr.

format of a major motion picture, I would sincerely suggest there is nothing

wrong with the proverbial ‘happy ending’.

It has become something of the fashion to expect dour, dark and depressing

conclusions in today’s movie culture. Personally, I live in reality. I don’t need

to see it on the screen. Hence, I have had enough doom and gloom to last at

least one lifetime. Besides, a good yarn is a good yarn – period; The Paper, running off one of the most

entertaining facsimiles of a ‘hot-off-the-presses’ front page re-conceived for

the movie screen. Extra! Extra! The Paper’s

a winner.

I am really not

loving Universal Home Video’s recent spate of Blu-ray releases. The Paper has an overly processed

video-esque appearance. While colors are bold and, at times breath-taking, the

image has been artificially sharpened; DNR also applied liberally to background

information. The result: this transfer sports an oft pixelated appearance:

digitally gritty without actually exposing the organic structure of indigenous

film grain. Contrast is solid, but we get

some intermittent moiré patterns in background information; fine details in

plaids and wood grain sporadically to suffer from jitter and those dreaded halo

effect. As John Seale’s cinematography rarely settles on any one moment where the

eye can study these discrepancies, the overall effect looks like image

instability and/or video-based noise; clogging up a visual presentation that

ought to have been flawless and stunning. The DTS 5.1 audio is adequately

rendered, with dialogue occasionally acquiring a slightly muffled characteristic.

As with Uni’s other back catalog Blu-rays, we get NO main menu or chapter

search options; subtitles are accessible. Honestly, I wish I could

single-handedly convince Universal’s executive brain trust (and I use this term

very loosely) that their skin-flint

approach to parceling off the studio’s history in barebones ‘exclusive’ editions like this one is a

really backwards-thinking approach to home video – period! If a new scan of an

old camera negative is worth doing it is definitely worth doing right…n’est

pas? Bottom line: recommended for content. The transfer is flawed. In 2018 I

would hope for, and expect far better! Regrets.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

3

EXTRAS

0

Comments