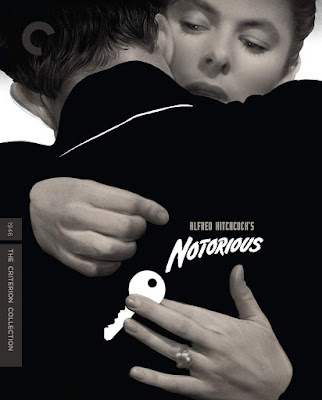

NOTORIOUS: Blu-ray (RKO, 1946) Criterion Collection

Few directors of

any generation have enjoyed the world-renown of Alfred Hitchcock.

Point blank: he is the master;

pioneering certain techniques that have oft been copied since, though arguably,

never duplicated. If imitation is the cheapest form of flattery, then Hitch’

has been flattered more than any of his movie-land brethren, and rightfully so.

By 1946, Hitchcock had reached something of an impasse in his working

relationship with David O. Selznick. In his native Britain, Hitchcock had been given

a certain autonomy to pursue projects on his terms, and moreover, to direct

them as he preferred. Selznick, however, was a fastidious producer with ideas

of his own. After having promised Hitch’ his debut, a retelling of the ‘Titanic’

(even, going so far as to purchase a derelict steamship, with plans for refurbishment

as a full-sized prop), this project (like a good many Selznick envisioned), was

not to pass. And Hitchcock, shortly after his arrival in America, was to

quickly learn that although his reputation had preceded him, it was not as

immediately regarded in the land where so many exemplary talents currently

resided. Indeed, Hitchcock languished under Selznick’s auspices while Selznick

became embroiled in countless delays on his opus magnum: Gone with the Wind (1939). Only in hindsight would Hitchcock’s

legacy with Selznick serve both men well – even if neither was to particularly

regard the other with any great sense of mutual admiration during its tenure;

Selznick, free of the epic investment on ‘GWTW’,

becoming as entrenched in Hitchcock’s American debut; a big screen adaptation

of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1940);

the only Hitchcock movie to win a Best Picture Academy Award. Much to Hitchcock’s

chagrin, this Oscar did not go to him, but rather, Selznick, as its producer

and this, along with Selznick’s constant interventions on the set, became the

basis for the curdling of their Anglo-American alliance as the decade wore on.

Throughout the

1940’s, Hitchcock increasingly resented Selznick’s ‘ownership’; Hitch’ under an

ironclad contract that afforded Selznick the right to simply loan him out at

will, taking a percentage off the top for his ‘services’. Although Hitchcock

would be allowed some latitude at RKO, Fox and Universal – even, the

opportunity to make his passion project, 1943’s Shadow of a Doubt – it distinctly irked him to know Selznick was

calling the shots – even from the sidelines. By the mid-forties, Selznick elected

to keep tighter reigns on his ‘star’ director. After all, Hitchcock had made

sure-fire box office for others. Between these, there had been misfires too

(1941’s Mr. and Mrs. Smith, among

them). But Selznick was concerned one of his most identifiable commodities was doing

his best for other studios. In hindsight, it is interesting to consider where Notorious (1946) falls into this timeline; caught between Selznick’s private

obsession with psychoanalysis, resulting in Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945), and, The

Paradine Case (1947) – the least successful of the Hitchcock/Selznick

collaborations; arguably, because Selznick saw it as a 3-hour crime epic, and

Hitch’ preferred to keep it an intimate, decidedly ‘English’ affair. In the

end, neither of these creatives got what he wanted. Perhaps, recognizing the need for a break, Selznick

loaned Hitchcock out – again to RKO – for Notorious;

a taut and tenacious thriller that easily ranks among a handful of truly

superior tales of espionage.

Notorious is both frankly adult and uber-sophisticated;

trademarks, typifying the best from Hitchcock’s British period, though

ironically subdued under Hollywood’s inscribed patina of glamor. It may have

been that the governing censorship had dampened Tinsel Town’s thirst for sin –

at least, on the big screen. But in Notorious,

Hitchcock has it both ways, with his soon-to-be all-time favorite, Cary Grant, startling

as the hard-bitten realist, denying himself the love of the proverbial ‘bad

girl’, plucked from obscurity by his FBI operatives, to play the part of a

double agent and infiltrate a secret Nazi organization working out of Buenos Aires.

Notorious offered Grant his meatiest

role to date. Indeed, Hitch’ had been greatly impressed by Grant’s ability to

toggle from lighthearted scamp to brooding and dangerous ne’r-do-well in Suspicion (1941) – a film for which

neither Grant nor Hitchcock preferred the ending imposed upon them by RKO and

the Production Code. But now, master and mate were free to explore all of the

macho cruelty inflicted upon one Alicia Uberman (the luminous Ingrid Bergman),

whose late father’s loyalties to the Third Reich afford Devlin a certain latitude

for blackmail, enough to prod Alicia into a loveless marriage as sexual bait

for a key player within the organization, Alexander Sebastian (the inimitable

Claude Rains). Like most of Hitchcock’s masterworks, the sleuthing derived

herein is mere subplot, even smoke screen for the roiling passions of these two

conflicted lovers, caught in a perilous ménage à trois.

Under his loan

out agreements, Selznick had enjoyed lucrative revenues for Hitchcock’s

services he could reinvest in his homegrown product. The pluses for Hitch’ were

distilled into a matter of distance from Selznick’s meddling stream of creative

consciousness; let loose, as it were, to pursue and reshape his vision of the

finished product according his own tastes. And Selznick too had grown weary of

attempting to ‘direct’ Hitchcock – derailed in these pursuits by Hitch’s clever

timing. Selznick always seemed to arrive on set during periods of inactivity,

resulting in his inability to make ‘suggestions’ on how to improve upon the

work. So, Selznick put together a

'package' deal for Notorious that

included the services of Hitchcock, Claude Rains, and, Ingrid Bergman (whose

contract Selznick also owned), before farming out the property, lock stock and

barrel, to RKO to produce and distribute. Mostly, Hitchcock would be allowed to

make the kind of picture he wanted to without outside intervention, even if

Selznick did keep a watchful eye on the production from afar. Meanwhile, Hitchcock

and screenwriter Ben Hecht concocted a silken caper that could stand on its

own. Selznick had campaigned hard for

Joseph Cotten to co-star as Cotten’s contract also belonged to him (ergo, more

money for another loan out). Perhaps knowing this, Hitchcock fought for – and was

given – Cary Grant as his star instead, RKO’s production exec, William Dozier,

invoking his clause to block Selznick’s request. After Ethel Barrymore and Mildred Natwick

turned down the role of Alex’s vicious and conspiring matriarch, Mme. Sebastian,

German actress Leopoldine Konstantin assumed the role.

Although the

movie in its finished form bears no earthly resemblance to its source material,

the impetus for Notorious was John

Taintor Foote’s two-part serial, The Song

of the Dragon, first published in the Saturday

Evening Post in 1921. Hitchcock’s reworked outline for the project met with

Selznick’s approval and Hitch’ soon left for New York for three-weeks’ worth of

collaboration with Ben Hecht on the script; an uncannily effortless and productive

partnership. Alas, by the time Hitchcock and Hecht were ready to present the

fruits of their labors, Selznick was in the thick of disastrous rewrites and

reshoots on Duel in the Sun – the colossus

western he had envisioned to rival, or perhaps even eclipse, his titanic

efforts on GWTW. At this juncture,

Selznick seemingly lost all interest in actually producing the picture himself

and arranged for RKO to do the heavy lifting on an outright purchase deal for a

cool $800,000, plus 50% of the profits. For

this, Selznick did receive a certain modicum of input, including hiring

Clifford Odets to rework Ben Hecht’s original screenplay; a move that irked

Hitchcock and caused Hecht to refer to Odets’ soupçon of high culture as ‘really loose crap’ which Hitchcock, in

the end, entirely ignored. Shooting from Oct. to Feb., Hitchcock held absolute

dominion inside several RKO sound stages. Even scenes supposedly taking place

outdoors were shot using a combination of intricate sets and rear projection –

all except for a brief ‘riding sequence’ where Devlin deliberately spooks Alicia’s

horse to encourage Alex’s chivalry and thus kick start their ‘cute meet’. This

sequence was shot at the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden in

Arcadia.

Thanks to

Hitchcock’s meticulous planning, the shooting of Notorious went smoothly. Initial apprehensions from Bergman – then,

prone to a slight nervousness – were allied when Grant took it upon himself to

guide his costar through several rehearsals. This working relationship proved

so successful it began Grant and Bergman’s lifelong friendship. Meanwhile, Hitchcock

endeavored to circumvent the Production Code by creating a new template for screen

passion, extending the Code’s steadfast rule about limiting kisses to 3 seconds

by breaking up one long kiss into multiple shots, eventually adding up to 2 ½ minutes.

In another instance, Hitchcock deferred to Bergman’s suggestion regarding Alicia’s

reaction to Devlin. Indeed, this was a major victory for Bergman, as much of a

departure for Hitchcock, whose usual adherence to his calculated designing of

every camera angle, set, costume, prop, and even sound cues, prior to arriving

on set, was legendary. Nevertheless, Hitch’ broke with precedence for Bergman,

allowing her to play the scene her way and openly acknowledging afterward that

her instincts herein had been spot on. Meanwhile, Hitchcock consternated over composer,

Roy Webb’s score. In hindsight, Webb’s cues remain one of the subtlest – almost

to the point of absence – in a Hitchcock movie. Webb was an RKO contractee,

noted for his superbly steadfast but understated contributions to Val Lewton’s

horror masterpieces. Hitch’ would have preferred Bernard Herrmann in his stead.

But Herrmann proved unavailable due to prior commitments.

From afar,

Selznick sent memos, suggesting Notorious

might benefit from a syrupy love ballad to be pre-sold on the hit parade. Mercifully,

in this regard, Selznick was vetoed. But Hitchcock was soon to admire Webb for

both his economy and general disregard for the grander musical gestures Selznick

so much adored. And although Webb and Hitchcock would never again reunite,

their collaboration on Notorious is

exemplified by Webb’s ego-less ability to see the picture both as precisely and

concisely in musical terms as Hitchcock had assembled it visually. Also, on

Hitchcock’s say, Webb would compose no ‘love theme’ to underscore the roiling

passions between Devlin and Alicia. Instead, wherever possible, Webb

interpolated waltzes and traditional Latin music to offset and compliment this

sparsity. In a film fraught with so many lush and evocative Hitchcock touches,

not the least being the dizzying rotation of the camera to evoke Alicia’s ‘next

day’ hangover, Notorious’ visualized

pièce de résistance is undeniably cinematographer, Ted Tetzlaff’s incredible crane

shot, effortlessly gliding down a second-story banister into the densely

populated foyer of Alex’s home, stealthily zooming in on an extreme close-up of

Bergman’s hand, nervously clutching the cellar key she has just purloined from

her husband’s key ring. The fluidity of this moment is seamlessly stitched to

the mounting and tense exchange of otherwise seemingly innocuous social banter

between Devlin and Alicia, the transference of the key from Alicia to Devlin,

and finally, their skulking off together, down to the cellar, culminating in

Alex discovering them, deliberately orchestrated in a passionate embrace to

deflect from their sleuthing behind his back.

Notorious is, in fact, a far more psychologically complex drama

than Spellbound – despite the latter’s

‘on the nose’ approach to

psychoanalysis. Grant’s FBI operative is perpetually sullen rather than sexy,

and emotionally distant. He pimps Alicia out as sexual prey, seemingly without

remorse or even an afterthought for her personal safety, but then becomes

wounded by a petulant jealousy when she plays the part above and beyond his

expectations. Despite Grant’s undeniable ‘drop dead’ good looks, his Devlin is

a fairly unsympathetic character – all business, and even cruel and manipulative

until the very end when it is almost too late to turn back and become chivalrous.

Conversely, Claude Rains – Grant’s physical antithesis (diminutive and

unprepossessing) is the more considerate and appealing suitor, leaving Bergman’s

enterprising and emotionally scarred double agent deliberately dangling in her

loyalties, or as Alicia directly puts it, “once

a tramp…always a tramp.” And one has

to sincerely empathize with Alex, whose demonstrative mother is actually the

real power behind the throne; an emasculating gargoyle, possessive and hovering

over his new marriage until she unlocks Alicia’s secret with all the blissful venom

of an insanely envious rival for her son’s affections. “We are protected by the enormity of your stupidity—for a time”,

she informs him, with a delicious satisfaction, more so for having snuffed out

his chances at romantic happiness. Despite his unholy alliances, it is Rains’ Alex

we fear for the most in the penultimate moments, as Devlin gingerly guides an

enfeebled Alicia down the grand staircase, past steely-eyed conspirators who

have just about decided for themselves that Alex is their weakest link and must

be dispensed with to ensure the preservation of their organization.

Notorious opens in a Florida courtroom where Alicia Huberman’s

father, John (Fred Nurney) has just been convicted of subversive activities in

support of the Nazi party. Departing in haste from the pry of flashbulbs and

reporters, his daughter Alicia, promptly retreats to a bungalow to drown her

sorrows in a devasting binge-soaked party populated by a carefree assortment of

sycophants. T.R. Devlin is a party crasher, toying with his host’s affections

as he bides his time, waiting for the others to pass out. In the morning,

Alicia awakens to discover Devlin hovering over her with a sobering request; to

infiltrate her late father’s organization of spies in South America. Alicia’s

past as a fast and loose party girl has preceded her arrival in town. Now,

Devlin uses this spurious reputation as leverage, pretending to be repulsed by Alicia.

Secretly, however, he harbors a growing sexual frustration to possess her for

his own. Devlin's boss, Capt. Paul Prescott (Louis Calhern) observes Devlin's

steadily mounting obsession and quietly pulls the plug on their burgeoning

romance. After all, Alicia's 'talents' for seduction are needed elsewhere.

Alicia is

employed to pursue one of her father's old friends, Alexander Sebastian (Claude

Rains); a lead proponent in the Nazi spy ring. Devlin sets up Alicia and Alex’s

‘cute meet’, startling Alicia's horse to encourage Sebastian to play the part

of her gallant rescuer. Sebastian takes this bait. Soon, he and Alicia are

inseparable. But their faux romance is frequently interrupted by Devlin's need

to be near and this, in increments, incurs Alex’s ire and jealousies. Alicia

confides in Paul and Devlin that Sebastian has proposed marriage. After some

consternation, mostly on Devlin's part, Alicia agrees to wed Sebastian to get

even closer to the truth. At first,

Sebastian does not suspect a thing. But during a lavish reception given at

their home, Sebastian is led to believe Devlin and Alicia have become

romantically involved behind his back. This, of course, is concocted subterfuge

to deflect his suspicions elsewhere, as the passionate kiss between Alicia and

Devlin he was meant to witness has been orchestrated to throw him off their

discovery of uranium found inside one of the vintage bottles inside Sebastian's

wine cellar. The rouse works only temporarily. Sebastian learns of Alicia’s truer

purpose after investigating the wine cellar for himself early the next morning.

Confiding in his mother, Anna decides the only way to save face within the

organization now is to slowly poison Alicia and make her resulting death look

like an accident.

At first, this

slow, steady poisoning goes virtually unnoticed. Alicia grows weaker and is

constantly attended to by the kindly Dr. Anderson (Reinhold Schünzel). Devlin

suspects Alicia’s paleness to be the result of wild nights, carousing at Casa

Sebastian. And even Alicia does not suspect – at first – that her husband and

his mother have unearthed her secret and are now, calculating her demise. However,

when Dr. Anderson inadvertently tries to drink coffee from a cup intended for

Alicia, Alex and Anna’s concerned correction informs Alicia of their treachery.

Only now, she is too weak to resist. Collapsing, Alicia is hurried upstairs and

placed under surveillance; Anna waiting for the inevitable to occur. Meanwhile,

having missed her latest informant’s rendezvous with Devlin, he suddenly realizes

Alicia is not sick or even delayed, but in grave danger. In direct violation of

orders, Devlin crashes Sebastian’s abode just as the Nazi organization has gathered

to discuss their latest plans. Hurrying upstairs, Devlin finds Alicia failing

but still alive. He gathers her in his arms and, despite Anna’s objections, now

threatens to expose everyone to the watchful conspirators assembled in the

foyer. Alex nervously concocts a story about Devlin being summoned to take

Alicia to hospital for treatment. However, once Devlin has Alicia in his car,

he locks the passenger door, preventing Alex from accompanying them in their

escape. Having deduced a fraud afoot, Alex is sternly summoned back into the

house, presumably to be ruthlessly dispatched, along with his scheming mother.

Notorious is unequivocally A-list Hitchcock, even more

remarkable, as it was made at a juncture in his career when Hitch’ regarded his

creativity as straight-jacketed by the studio system and its Production Code. One

has to sincerely admire Hitchcock and Ben Hecht for their chutzpah, the daring in

presenting American officials as spurious merchants of prostitution, not above

sexual blackmail and other amoral devices, toxic and taboo for any movie from

Hollywood’s golden age, but particularly one made and released at the height of

WWII, when America regarded itself, and was otherwise perceived around the

world as the ‘great and virtuous liberator’ of a European hemisphere in flames.

In the shadows of this towering edifice to male chauvinism, Hitchcock also gives

us with his first genuinely unflattering depiction of motherhood; Anna

Sebastian - a thoroughly corrosive viper, inadvertently contributing to her own

demise and that of her ineffectual son. The acting throughout Notorious is uniformly superb;

particularly Cary Grant, who eschews his otherwise trademarked lovable sex

symbol, herein transformed into a thoroughly tortuous figure of self-doubt,

loathing and regret. Hitchcock and Grant

would toil together again, in two of the master’s most frothy and fun misadventures;

To Catch a Thief (1955) and North by Northwest (1959). But only in Notorious do we get the ‘other side’ of

Grant’s persona – the one usually masked from public view.

Notorious arrives on Blu-ray – again – via Criterion’s ‘new’ 4K

digital restoration. Before we get overly excited about this, let us make an

observation by way of comparison with MGM’s Blu-ray release from nearly 6 years

ago. Criterion’s has a lesser bit rate. This does not translate into lesser

image quality. On the flip side, overall improvements are marginal at best. Notorious,

this second time around, sports a slight edge in intermittent image sharpness. Also,

by direct comparison, the old MGM release now appears ever so slightly

horizontally stretched. But you really have to be discerning to pick out these

differences. In motion, both discs appear as though derived from the same

source. And while, on occasion this new image harvest advances, it is not the

quantum leap forward, experienced on Criterion’s updated Blu of Rebecca (1940). Notorious’ image is generally free of age-related artifacts. Tonality

is solid with clean whites and velvety blacks. As RKO was not exactly at the

forefront of film preservation, the elements here are softly focused

(unintentionally). The lossless PCM mono audio bests the Dolby Digital from MGM’s

Blu, but again – you have to strain to hear these subtle improvements, most

obvious in the spatial spread in Roy Webb’s main title underscore.

Criterion has

ported over all of MGM’s previously issued special features, including a pair

of audio commentaries from 1990 and 2001, featuring Rudy Behlmer and Marian

Keane. Criterion also offers up a host of new and very welcomed reflections: individual,

nearly half-hour-long interviews with biographer, Donald Spoto,

cinematographer, John Bailey, filmmaker, Daniel Raim, and, scholar, David

Bordwell. The most comprehensive extra

is ‘Once Upon a Time…Notorious’; an hour-long documentary from 2009 with highlighted

input from Isabella Rossellini, Peter Bogdanovich, Claude Chabrol and Stephen

Frears, among many others. Capping off our enjoyment; snippets of newsreel

footage, the Lux Radio adaptation, trailers and teasers; plus, a printed essay by

critic, Angelica Jade Bastién. Bottom line: Notorious is one of Hitchcock’s crown jewels. In a

career richly populated by such gems, it stands apart – even from Hitchcock’s

other ‘war-themed’ espionage thrillers; Foreign

Correspondent (1940) and Saboteur (1942).

Even if you already own the old MGM Blu, you will want to snatch up this

reissue, as it not only offers nominal improvements to the overall image

quality of the feature, but really delivers the goods with a comprehensive assembly

of meaningful extras. Very highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

5+

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

5+

Comments