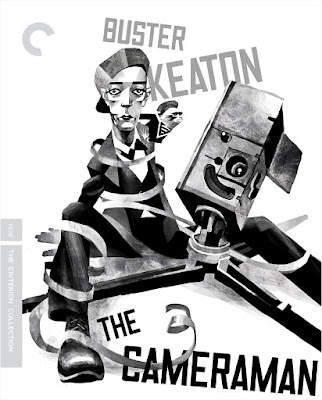

THE CAMERAMAN: Blu-ray (MGM, 1928) Criterion

For me it is impossible to view Buster Keaton’s 1928

silent masterpiece, The Cameraman without emerging conflicted, a deep

sense of admiration and regret. On the one hand, The Cameraman marks the

absolute zenith of this stone-faced denizen’s complete command of the silent

cinema language; Keaton, with narrowly an eyebrow to be raised, or, seemingly

to illustrate any emotional response from the neck up, somehow, miraculously – ingeniously

– able to contain and express the entire circumference of human desire, pathos

and tragedy writ large and invigoratingly for all the world to see. Like his

contemporaries then, Keaton was irrefutably an artist with an instinct and

creative bent that could not be contained within the two-dimensional world of

the movies. He seemed to appear out of nowhere and then, with illusory effortlessness,

to make one believe his underdog was capable of the most audacious triumphs

against humanity’s mad inhumane noise. This is the Keaton I choose to regard

when viewing The Cameraman. Alas, there is another to consider – the artist,

not only at the apex of his craft, creative juices flowing with spellbinding

precision to achieve the myriad of epic stunts within the picture, but as much

at the beginning of a sad, steady decline in his creative autonomy. Why Keaton

should have chosen to sign away his artistic license to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer is,

frankly, beyond me. Clearly, the offer – whatever its particulars, financially

speaking – was too good to pass up. But from this moment forward, Keaton would come

to realize he had effectively signed away his rights as a filmmaker, just

another cog in the great wheel of the studio system with ‘more stars than

there are in heaven’.

Actually, the indictment against MGM is not entirely

binding, as, two years before The Cameraman, Keaton had made The

General (1926) for United Artists – the company, co-founded by D.W.

Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. While widely

regarded today, The General was a costly flop then, UA imposing a

production manager on Keaton’s subsequent movies to monitor his expenditures,

but also reign in his creativity. For an artist, being told what he could and

could not do proved too much, and thus Keaton departed UA for MGM in the Fall

of 1927, his loss of independence exacerbated by the coming of sound. In years yet

to follow, Keaton would regard his arrival at Hollywood’s grandest studio as

the biggest misfire of his life. For although he had been assured a level of

autonomy by L.B. Mayer, such promises were quick to evaporate once Keaton was

unhappily ensconced on the backlot and forced to abide by his ironclad contract.

Under Metro’s umbrella, Keaton would retain his ‘star’ status, but virtually

lose the ability to direct himself in pictures. Although The Cameraman

appears to have escaped such scrutiny, the studio officially appointed Edward

Sedgwick to direct. But Keaton was appalled to learn he would have to use stunt

doubles for the more daring action set pieces.

In his prime, Keaton never used a double. Understandably, MGM was trying

to protect its investment – a wounded star, makes no money. Given Keaton’s

misery at MGM, the pictures he made there were among his biggest box office

bell-ringers; Mayer, teaming Keaton with Jimmy Durante for a string of quickly

shot programmers that were all the rage with audiences. But Keaton was so vocal

in his demoralization during the making of 1933's What! No Beer? he was

fired, despite the movie being released to great interest and considerable

profits.

From here, Keaton made half-hearted attempts to re-enter

the picture-making biz, first in Europe, then, in a sting of cheaply made

2-reelers for Educational Pictures back in Hollywood, relying on his storefront

of seasoned Vaudeville gags to buoy this otherwise forgettable spate of sixteen

projects. Somewhat begrudgingly, Keaton returned to MGM in 1937 as a gag writer.

He also appeared in ten 2-reel comedies for Columbia between 1939 and 1941. But

again, Keaton soured on the level of bureaucratic control exuded by the studio

on his creativity and, when Columbia offered to renew his contract, Keaton

instead declined. From this point forward, Keaton concentrated on writing gags

for up-and-coming comedians like Red Skelton and Lucille Ball. Under his

contract with MGM, he also agreed to appear in character parts in some of their

prestige pictures, a highlight from 1949, In The Good Old Summertime,

co-starring Judy Garland and Van Johnson, where he played nephew to S.Z. Sakall’s

aged proprietor of a music shop. He was also loaned out for cameos in Billy

Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950), and Michael Todd’s Around the World

in 80 Days (1956).

Looking back on The Cameraman as Keaton at a

crossroads in his career, one can see the innate value of the piece as a purely

escapist, often audaciously original, and, a grand hurrah for Keaton –

celebrating his film-maker’s prowess, and, as yet, not entirely aware that the

epoch of sound, and, his pact with the studio have thus conspired to seal his

fate as an irrefutable auteur of silent cinema. Among its many distinct

virtues, The Cameraman is a shrewd charade, only in hindsight, to be

considered as the apogee of an astonishing tenure in ground-breaking and imperishable

entertainments. Who better than Keaton, to cast himself as thinly veiled alter

ego, tintype photographer, Buster Luke Shannon – who trades his Browning to

become a sincerely luckless newsreel cameraman, raring to strike an indelible

chord with his new employer, Editor Edward J. Blake (Sidney Bracy) and winsome

Metro office temp, Sally Richards (Marceline Day) with whom he becomes smitten

but who favors the more physically robust, Harold Stagg (Harold Goodwin). Traversing

mid-town for his big scoop, Shannon goes for an unanticipated, and thoroughly

waterlogged swim to save Sally from drowning during a regatta, gets inveigled

in a Chinatown Tong War, and, befriends a wayward monkey (Josephine). While it

is Edward Sedgwick’s name just under the main title, it’s rather obvious Keaton

is behind the camera, or rather, calling the shots in which he so readily

appears, his imagination unleashed upon the backlots, building from one

adventuresome vignette to the next – all of it leading to a gloriously poignant

finale.

While last-minute studio second-guessing, and

tinkering, arguably blunted the clear-eyed impact of Keaton’s vision, it could

not entirely diminish the results. And, all kidding aside, The Cameraman

remains an iconic picture in Keaton’s canon. Keaton’s verve for the material

and his film-maker’s chutzpah are able to conceive valor in this milquetoast hero

, and, his pig-headed determination to make a good picture, in spite of the

creative stringency imposed on him by the studio – to have included having to

submit his finished screenplay before the project could be green-lit, with all his

gags already factored in (Keaton, in rare form – always – as an artist who ‘discovered’

some of his best material through improvisation, and work-shopping between takes),

and, even more insulting, to be stripped of his directorial credit, despite the

fact, most of what we see is his work – both in front of and behind the camera –

The Cameraman contains several cleverly-concocted vignettes that remain

time-honored standouts of the silent era. The deftly staged, one-man baseball

game at Yankee Stadium immediately comes to mind, as does the inspired ‘booth scene’,

in which Keaton and another player (Edward Brophy) frustratingly

contort to fit into a narrow enclosure while attempting to try on bathing

suits, and, finally, Keaton’s narrow escape from an all-out street war in

Chinatown, losing the legs of his camera tripod one at a time in a hailstorm of

bullets.

In a career and a tradition prone to hyperbole, Keaton

endures as one of the most fastidious artistes of the 20th century.

His mastery is manifest both physically and psychologically; The Cameraman,

his most remarkable homage to that bewildering and generally indescribable

organic nature of picture-making. Emancipated from his crippling shyness by a primate

he presumes to have inadvertently killed (the moment, when the monkey initially

stirs, peeling back its white shroud, shot with no less reverence than Lazarus,

rising from the dead), the sidekick, in fact, to put all Keaton’s fellow

players to shame, The Cameraman postulates that to be a novice is akin to

a sort of antediluvian neoimpressionist, mostly to benefit from this topsy-turvy

world of unfettered chaos. Leave it all up to the monkey, Keaton seems to be

saying. And ironically, where Keaton’s alter ego is concerned, truer words were

never spoken. The Cameraman is both boisterous and flamboyant, as we navigate

the impossible failings of this loveably flawed and seemingly witness

fish-out-of-water through a series of unfortunate circumstances, exacerbated by

his arrival on the scene with a camera. If nothing else – and there is so much

more to derive pleasure from here – then, The Cameraman must have been

very dangerous to film; a real/reel life-and-limb ordeal for Keaton who,

ostensibly, was no stranger to suffering for his art. Keaton had, in fact,

broken his neck on the set of The General (1926). And, in an era when artists

were, if not encouraged to take risks, then, at least to have their executive

brain trusts looking the other way while they experimented with feats of

extraordinary daring, for no other reason than to get it in the can, The

Cameraman is the opus magnum of Keaton’s over-indulgences in this

self-professed ‘theater of pain’. Some

of the stunt work here is truly cringe-worthy. Impossible to imagine the level

of nail-biting hysteria some of Keaton’s efforts here must have elicited from

first-run theater goers; Keaton, raising the ante to new heights as he plunders and prat-falls his way through these turbulent vignettes – all for the sake of

a girl.

Criterion has finally come around to releasing The

Cameraman on Blu-ray – a Herculean effort, considering the fragmented and

damaged nature of these archival elements. This new 4K restoration is achieved via an

alliance between Criterion, the Cineteca di Bologna, and Warner Bros. – the present

custodians of the old MGM library. Keaton’s original cut has remained unseen

since 1951, shorn of 3-mins., presumably, not to have survived the passage of

time. Culling together elements from a 35mm second generation fine grain, 16mm reduction,

housed with the Library of Congress (the actual primary source for this

restoration) and a 35mm dupe positive from MGM's compendium theatrical release,

The Big Parade of Comedy (1964), all of these

disparate elements have been scanned at Warner’s MPI facility in Burbank, with

the final ‘restoration’ work performed at 12 Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna,

Italy. Disparities in overall clarity abound. But honestly, given the

horrendous nature of the movie’s existing elements, what has been achieved here

easily bests anything The Cameraman has looked like in well over 50

years, with a hint of century-old, age-related anomalies still baked into this transfer,

yet steadily to have improved on the overall presentation - richer contrast, better

resolved reproduction of film grain, and, yielding a level in fine detail

otherwise presumed to have been lost to us for all time in previous mastering

efforts. We get a PCM 2.0 audio with a new score from Timothy Brock, recorded

by the orchestra of the Teatro Comunale di Bologna in 2020.

Extras include Glenn Mitchell’s mostly excellent audio

commentary from 2004. Keaton’s follow-up to The Cameraman, Spite

Marriage (1929) is also included here, derived from a new 2K restoration,

with an audio commentary from John Bengtson – also recorded in 2004. Criterion

has also shelled out for a brief featurette in which Daniel Raim consults

Bengtson and historian, Marc Wanamaker. So Funny It Hurt: Buster

Keaton and MGM is a 38-min. documentary by Kevin Brownlow and

Christopher Bird, hosted by James Karen. We also get, The Motion Picture

Camera (1979), a ½ hr. documentary by Karl Malkames, fully restored and

scanned in at 4K. Finally, we get a 15-min. reflection piece by James L.

Neibaur, exclusively produced for this release, and, to cover Keaton’s movie

career post-MGM. Bottom line: The Cameraman is Keaton’s last great

achievement, and, although imperfectly represented here, is nevertheless, as

richly rewarding to behold as the day it premiered. Criterion’s jam-packed

deluxe edition, with goodies aplenty, is sure to whet the appetite for more

Keaton to follow – hopefully. In the meantime, permit us to worship at the altar

of old ‘stone face’ – truly, one for the ages! Very highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

3.5

EXTRAS

5+

Comments