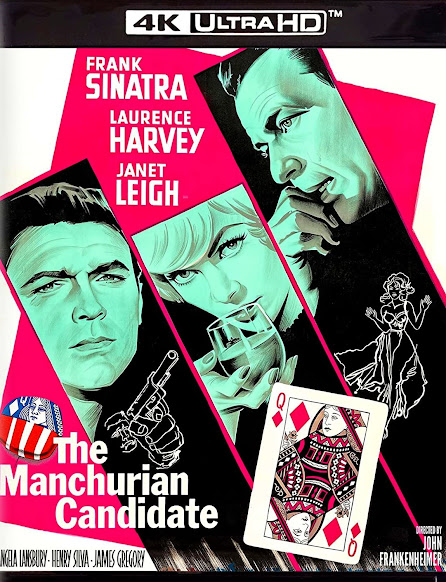

THE MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE: 4K UHD Blu-ray (United Artists, 1962) Kino Lorber

“The Manchurian Candidate is a classic example of the old adage – you are no better than your material. Richard Condon wrote a great book. Everything that critics praise in the film is in that book – the dream sequence, the scene in the train, the character of Raymond’s mother and so much more. In fact, there were three or four scenes from Condon’s book that we were unable to put in the film…something I have always regretted. But George Axelrod wrote a marvelous screenplay which I followed faithfully. The actors were wonderful. The cameraman, Lionel Lindon, was the finest I have ever worked with…in short, The Manchurian Candidate was one of those experiences where everything went right!”

- John Frankenheimer

Undeniably, the most prophetic

movie of its generation, as well as perennially revealing to each new one to have

followed it, John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate (1962) has

since entered the annals as American folklore as a much contested, if

irrefutable oracle of the times, inadvertently to earmark the age of incredulity

in ‘post-modern politics’. Within months of its release, President John F.

Kennedy’s assassination in Dealey Plaza recreated, with eerie verisimilitude,

the elemental paranoia suffusing this movie’s plot and its penultimate

resolution - a political murder for hire, reluctantly perpetrated by a reformed

Raymond Shaw (the spectacularly steely, Lawrence Harvey). Immediately following

Kennedy’s assassination, star, Frank Sinatra, The Manchurian Candidate’s

most ardent supporter and participant (in fact, the entire reason Frankenheimer

was able to get his movie off the ground in the first place) used his clout to pull

it from circulation out of respect for the grieving Kennedy family; perhaps,

also, to save face, as a close friend to this omnipotent American dynasty.

In many ways, America never has recovered

from Nov. 22, 1963. Kennedy’s presidency represented the promise of a very

short-lived dream for the future without the spoils of a pax Americana

dictating policy to all points of the world. Without a true visionary at the

helm, we have increasingly forsaken that dream for a blunter understanding;

that politicians somehow act as little more than cogs in the overriding

machinery collectively consigned as ‘government’ advancing certain agendas for

which no one individual appears to take credit, but where the de facto leader

of the day professes peace to the populace while advancing the implements of

war beyond American shores. The

Manchurian Candidate’s resurgence as a bona fide classic today, typifies,

as much as it taps into our fascination with conspiracy theories. The movie’s

artistic clairvoyance is even more incredibly disturbing today. Of course,

Frankenheimer – then - had absolutely no idea he was embarking upon such a

cultural touchstone.

The Manchurian

Candidate lacks nuance. Yet, there are great subtleties scattered throughout its

tautly scripted narrative precipices, beginning with Frankenheimer’s

ingeniously worked out 360-pan from the innocuous ‘ladies auxiliary,’ attending

a hotel lecture of the horticultural society, to mutate into a demonstration

exercise of the Communist Party, hosted by the leering Dr. Yen Lo (Khigh

Dhiegh). Lo orders an unknowing Raymond Shaw to casually murder two of the

‘lesser’ men in his kidnapped battalion. Without fail, or even in

reconsideration of his actions, Shaw shoots Private Bobby Lembeck (Tom Lowell)

through the forehead, then, coolly strangles Private Ed Mavole (Richard LaPore)

as Lo’s committee, and the rest of the men entrusted in Shaw’s care

complacently observe. Alas, these reprogrammed memories begin to seep into the

subconscious of two of Shaw’s surviving soldiers: Corporal Allen Melvin (James

Edwards) and Major Bennett Marco (Frank Sinatra). Each experiences hellish

nightmares, sweat-soaked and emotionally incapacitated, despite their pre-programmed

thoughts to consciously refer to Raymond Shaw as “the kindest, bravest,

warmest, most wonderful human being” they have “ever known” in their lives.

Herein, we pause to tip our hats to

ole blue eyes. Sinatra gives one of his ‘top three’ greatest dramatic performances

(the other two – in 1953’s From Here to Eternity, and 1955’s The Man

with the Golden Arm), herein, genuine, disturbing, and fraught with

psychological complexity as an almost fatally stricken seeker of the truth. Somehow,

Sinatra allows us to see the inner workings of Marco’s mind as it repeatedly

struggles, grinds to a halt, and finally, with great determination, is liberated

from these artificially created mental barriers and roadblocks. There is a sort

of tortured desire at play, barely to reconcile what Marco instinctually knows

to be true with the myths imbedded into his formalized thoughts. Marco’s piecing

together of another planned political assassination is only partly successful,

as Shaw publicly executes the party’s most demonic participant, his own

menacing mother, Eleanor Shaw Iselin (an incredibly vicious Angela Lansbury)

and her cardboard capitalist crony/husband, Sen. John Yerkes Iselin (James

Gregory, so transparently a knock-off of Washington ‘witch-hunter,’ Sen. Joseph

McCarthy). Shaw then takes his own life with Marco as witness. What might have

played before the Kennedy assassination as fictionalized – even operatic –

grand tragedy with ancient Greek and Shakespearean overtones imbedded into the

George Axelrod screenplay, post-Kennedy bears forth the undeniable

grey-shadings of a Lee Harvey Oswald and/or Jack Ruby; men, not unlike our

Raymond Shaw, of manipulated conscience, patsies planted by subversive forces

where they can do the most harm.

Real history is a murky water,

stirred with a fatalist’s stick by conspiratorial hands. By contrast, The

Manchurian Candidate was a meticulous – almost telescopically focused –

stream of consciousness, invested with a spark of fitful brilliance from Frankenheimer

who, upon securing Sinatra’s services (giving him the keys to the kingdom to

make his movie, seemingly his way) instead had to maneuver around Sinatra’s

‘Chairman of the Board’ chutzpah. Somehow, Frankenheimer manages a coup here – star

and director in symbiosis with their creative détente resulting in some

tenuous, though never entirely strained relations over artistic differences. “Sinatra

was always better on the first take,” Frankenheimer later admitted, a

stumbling block when it came to shooting the pivotal scene where Marco

confronts Shaw with a deck of cards after already having figured out how an

innocuous game of solitaire holds the key to de-bugging Raymond Shaw’s

programmed protocol.

Frankenheimer and Sinatra did only

one take of this pivotal scene, each convinced they had the best possible

performance already in the can. Regrettably, cinematographer, Lionel Lindon’s

viewfinder was slightly out of focus. Frankenheimer reluctantly showed Sinatra

the hazy footage and both men agreed to go back and reshoot the scene from

scratch the next day. Alas, neither was satisfied with the various attempts

made on day #2. By some estimates, Sinatra did up to ten takes in his

ambitiousness to recapture the magic of his primary effort. Exacerbated by his

inability to live up to these expectations, Frankenheimer agreed to use the

first, slightly out of focus, footage in the final release print, mildly amused

when various critics championed this sequence as a streak of absolute genius

with Frankenheimer apparently going out on a limb to show the audience Shaw’s

hazy POV of Marco.

In Condon’s novel, Marco knows

Shaw’s mother is his American operative, an incestuous puppet master, tugging

on the strings. Using his stacked deck of cards, Marco reprograms Shaw to

murder Eleanor instead, thus, not only foiling her planned assassination of the

only viable presidential candidate to beat her husband, but also taking out one

of the top-tier operatives of the Communist Party. Owing to the stringencies of the production

code, Frankenheimer was barred from suggesting as much in his movie. Revenge, a

dish best served cold, was out. So, with Axelrod, Frankenheimer ironed out the

kinks to have Marco discover Eleanor only moments after he has already engaged

Shaw in his fixed game of solitaire, nobly absolving Shaw of the crime of

matricide. Hence, Shaw kills Eleanor and Iselin, partly to exorcise a lifetime

of pent-up animosity; also, partly to avenge the murders of at least five

innocent people (including his former boss, newspaper magnet, Holborn Gaines

(Lloyd Corrigan), his beloved bride, Jocelyn (Leslie Parrish) and her father,

Senator Thomas Jordan - John McGiver) who, ostensibly, were killed by Eleanor –

not her son, under the influence.

Initially, Frankenheimer approached

Sinatra and co-star, Angela Lansbury with a copy of Richard Condon’s dark

political thriller. Having just finished working with Frankenheimer on All

Fall Down (1962), Lansbury recalls how determined he was to get her for the

part, marching up and slamming down a copy of Condon’s novel on the desk,

declaring “Here is your next project.” “His enthusiasm was so

infectious,” Lansbury would later recall, “I read it and just thought,

if John thinks I can do this, I’m going to do it…and so very lucky that I did.”

It is difficult to imagine what Frankenheimer saw in Lansbury, either as a

performer or woman, that would have made her ideal casting for the malevolent

and perverse, Eleanor. While Lansbury had played saucy tarts with suspicious

convictions all the way back to her first picture, Gaslight (1944) and

would continue to appear in roles requiring a strong, unapologetically

enterprising female presence (the prostitute, Em, in The Harvey Girls

1946, or the morally ambiguous newspaper maven, Kay Thorndyke in State of

the Union, 1948, two examples) she had never before given herself so

completely to a truly vial and remorseless creature.

Eleanor Shaw Iselin is a morally

repugnant barracuda; Lansbury, loosely basing her portrait on the various

Washington socialites she met while doing research. A matriarch in name only,

Eleanor engages in the brutal emasculation of her ineffectual second husband,

orchestrates the assassination of his political rival, and, manages an

incestuous relationship with her adult son. For sheer disgust, there was

nothing to match the now infamous kiss on the lips Lansbury’s curt maven

initiates on her mentally paralytic offspring, simultaneously controlling his

thoughts as she dominates him physically. Two things make this moment

insidiously delicious. First, Lansbury’s whispered – even affectionate –

plotting of the final coup, even as she promises Raymond to grind all those

responsible for his brainwashing into the dust. Second, Lawrence Harvey’s

minimalist conveyance of complete acquiescence under such mind-bending

influences, yet perhaps, also, desperate affirmation for the woman he dare call

‘mother’. Despite Shaw’s implacable contempt for humanity and women in

particular, our empathy is with his psychologically scarred surrender. Harvey’s

subtly panged performance translates to Shaw’s inability to refuse any request

made after having heard the tag line: “Raymond, why don’t you pass the time

by playing a little bit of solitaire?” Harvey gives us superficial, even

edgy facial tics, and a lost, far away, glazed stare. But it’s what he is able

to convey going on inside – a hellish tug-o-war he is too timid to defeat, that

causes him to suddenly become submersed up to his chest in the icy waters of a

half-frozen Central Park lake, that really makes us believe in Shaw’s defeatism.

Interestingly, Condon considered The

Manchurian Candidate as pure satire. To understand the book and the movie

from this perspective, if at all possible, it is first necessary to reconsider

the political climate prior to Kennedy’s assassination. Indeed, only four

sitting presidents had been murdered while in office, the last – William

McKinley, all the way back in 1901 by Polish anarchist/steel worker, Leon

Czolgosz. McKinley’s slaying directly

resulted in the passage of legislation by Congress, charging the Secret Service

with protection of the Commander and Chief whenever he appears in public. While

not immune to further attempts made on the lives of standing presidents and

presidential hopefuls this newly instated military presence nevertheless proved

a formidable safeguard to the office, and, also, a deterrent to would-be

assassins. Hence, by the time Condon published The Manchurian Candidate

political assassination must have seemed highly unlikely, or a thing of the

past. In hindsight, which is always

20/20, Frankenheimer’s approach to Condon’s material was subconsciously more

direct; together with cinematographer, Lionel Lindon, applying a faux

documentary style that, only in retrospect, would take on its more piquant and

onerous reflection of these pervading winds of change already contaminating the

political pantheon, the 1960’s quick to become the antithesis of Kennedy’s

golden-era pax Americana.

The Manchurian

Candidate opens with a prologue set in 1952 at the height of the Korean War.

Staff Sergeant Raymond Shaw collects his troops from an Asian brothel for an

overnight military raid. But Shaw and his platoon are ambushed after their

guide, Chunjin (Henry Silva) betrays the outfit, taken by helicopter to

Manchuria. Immediately following the main titles, we learn Shaw is to be

awarded the Medal of Honor for bravery upon the recommendation of his platoon’s

commander, Capt. Bennett Marco. What neither realizes, along with all but two

of the remaining battalion, have fallen victim to an insidious brainwashing

perpetuated by Dr. Yen Lo. Nightly, Marco and fellow officer, Cpl. Allen Melvin

are plagued by reoccurring nightmares, idly to observe Shaw casually murdering

fellow soldiers, Ed Mavole and Bobby Lembeck at Lo’s behest merely as an

exercise in his mental reconditioning. With his wife’s encouragement, Melvin

writes Shaw to inquire if he has been having similar hallucinations. This

correspondence is virtually ignored by Shaw.

Meanwhile, Shaw’s arrival on U.S.

soil is met with ticker-tape parade, thanks to his enterprising mother,

Eleanor, who wastes no time exploiting his status as a war hero, merely to market

the campaign ambitions of her second husband, Sen. Iselin. Raymond is repulsed,

almost immediately distancing himself by accepting a job for New York Times

editor, Holborn Gaines, who is vehemently opposed to Iselin. Most recently, Iselin has been seen in his

McCarthy-esque demagoguery, railing against the Secretary of Defense (Barry

Kelley) during a televised conference, declaring the Secretary has prior

knowledge of at least two-hundred-and-seventy known card-carrying members of

the communist party presently working within the U.S. State Department. Or is

it a hundred-and-twenty? Having fabricated the entire allegation, Iselin is

never entirely certain of the actual number.

Marco, who has been recently appointed in charge of the Secretary’s PR,

is powerless to stave off the ravenous inquests that follows Isley’s outburst.

A short while later, Marco’s superior, Colonel Milt (Douglas Henderson)

relieves him, ordering an immediate respite from the fray. Marco confides there

is something rotten about Shaw’s Medal of Honor. While publicly, Marco cannot

resist referring to Shaw as “the kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful

human being” he has ever known, he confesses this statement to be untrue.

Shaw was an aloof, dreary and unsympathetic leader, utterly to lack even baseline

compassion for his fellow man.

Nevertheless, Marco takes Milt’s

advice. Suffering another bout of crippling anxiety while aboard an eastbound

train, Marco’s nervous breakdown is delayed by a brief encounter with

empathetic, Eugenie Rose Chaney (Janet Leigh). To ease Marco’s spirits, she

shares something from her past, including her failed engagement plans. It’s all

‘small talk’, but it eventually leads to bigger things. Only a short while

later, Rose breaks off her engagement and moves in with Marco, guiding him

through a labyrinth of past regressions until, at last, he taps into an

understanding of what has been done to him back in Manchuria. Returning to

Washington with renewed vigor, Marco gets Milt to show him a dossier on known

figures in the communist organization, easily identifying several, including

Yen Lo. Learning of Allen Melvin’s letter to Shaw, Marco has Melvin called in

for questioning. Melvin independently picks out the same faces from the

dossier, causing Milt to take notice of these unrehearsed similarities.

Marco and Chunjin inadvertently

cross paths when Marco makes an impromptu visit to Shaw’s apartment,

discovering Chunjin presently working as Shaw’s man servant, but actually

assigned by Lo to keep a watchful eye on Raymond’s renewed conditioning. Marco

and Chunjin engage in a hellacious karate fight. This puts Chunjin in the

hospital. The actual fight, staged with a stuntman’s precision, rarely using

doubles, caused Sinatra to break his finger. Marco’s suspicions are confirmed.

Shaw has been abducted by Lo under the pretext of having been struck by an

automobile, presently said to be convalescing at a retirement facility, but

actually enduring more ‘conditioning’ in a clinic managed by communist crony,

Comrade Zilkov (Albert Paulsen). Zilkov demands Shaw murder someone on Lo’s

orders in order to test ‘the killing machine’ they have created. Lo reluctantly

agrees. Shaw is let loose on his boss, Holborn Gaines. The murder unsolved,

Marco is nevertheless thoroughly convinced Shaw has committed this crime. He

is, however, not entirely certain of Raymond’s guilt as part of Shaw’s

reprogramming has managed to expunge guilt by creating a complete absence of

acknowledgement after the fact as one of the mental triggers switching on and

off again in Shaw’s psyche after the game of solitaire has been invoked.

Shaw enjoys a temporary retreat to

the country where he meets and almost immediately falls in love with Jocelyn

Jordan, the daughter of Sen. Thomas Jordan. She nurses him from a poisonous

snake bite and for the briefest wrinkle in time, Shaw finds unobstructed

serenity with Jocelyn and her father, whom he comes to greatly admire, not the

least for his opposition to Iselin’s bid for the White House. Buoyed by the

euphoria of their burgeoning romance, Jocelyn and Raymond are married on the

sly, confounding Eleanor, who is jealously opposed to this love match.

Believing he has struck a blow for his own independence Raymond returns to New

York. Marco, alas, is certain Shaw is quite unaware he is a ruthless assassin.

Marco pulls Jocelyn aside and implores her to get Raymond to turn himself in,

or at the very least, be subjected to medical testing before he can do any

further harm. Instead, Jocelyn naively pleads with Marco not to press the

point. He gives her forty-eight hours to use her influence to convince Raymond

he must surrender himself to the authorities. Now, Eleanor invokes the game of

solitaire, ordering Shaw to quietly go to Jordan’s townhouse and murder him

with a silenced pistol. Unhappy chance, Jocelyn is also home. Shaw’s conditioning

kicks in. He murders his new bride without even flinching, quietly departing

the scene, still unaware of the crimes he has only just committed.

Regarding the ever-rising body

count in The Manchurian Candidate, Frankenheimer cleverly elected to offset

the violence of these later murders with stylized representations in place of

the more graphically staged killings of Lembeck and Mavole. We never see Shaw kill

Holborn Gaines, the crime obstructed by Frankenheimer reframing of the action

with Shaw’s back to the camera, entirely filling the frame moments before we

fade to black. For the Jordans’, Frankenheimer comes up with an even more

artful and effective terror, photographed almost entirely from a low angle and

the POV of Raymond’s silenced pistol clutched in his hand, the bullet piercing

through a carton of milk grasped in Jordan’s hand, its white gusher a

substitute for the lethal and bloody wound. Jocelyn’s fatal shot is inflicted

from a considerable distance away from the camera and, again, at a low angle,

allowing for Shaw to casually step over her lifeless corpse, dramatically

splayed upon the checkered tile floor in her negligee as Thomas’ disbelieving,

frozen stare peers directly into the lens in close-up from the bottom right of

the frame, a moment hauntingly played out in almost complete silence, save the

subtle shuffle of Shaw’s shoes as he sleepwalks away.

The next day, Iselin feigns shock

and sorrow over the brutal double homicide, fielding questions from a small

army of reporters. Marco returns to the

apartment he shares with Rose, carrying a copy of the Times with the screaming

headline announcing the murders. He blames himself for allowing Jocelyn to persuade

him to remain silent. But now Shaw contacts Marco, already begun to realize

something is terribly wrong. Earlier, Marco was stunned to quietly observe as

an innocuous suggestion made by a barkeep, regarding a game of solitaire, made

to another customer entirely, suddenly triggered Shaw to mechanically take a

taxi and plunge himself square in the middle of a very frozen Central Park

lake. As an interesting aside: this stunt was performed by Lawrence Harvey wearing

a wet suit beneath his costume, with divers awaiting beneath the waters to

ensure he would not become entirely submersed. Harvey was then immediately

hoisted from this frigid soup and ushered into a nearby heated tent, given a

change of clothes and snifter of brandy to warm his innards.

Marco learns of Shaw’s whereabouts,

situated in a seedy hotel overlooking Madison Square Gardens where he is

awaiting instructions from his American operator regarding his penultimate

assignment - the assassination of presidential nominee, Benjamin K. Arthur

(Robert Riordan). Recognizing the card game – and particularly, the Queen of

Diamonds - as triggers meant to ‘hotwire’ Shaw’s psyche, Marco stacks the deck

in their favors with each new Queen revealed, ordering Shaw to regress into his

back catalog of sins committed under acutely heightened and hypnotic duress.

Marco commands Raymond to forget about the game, to forego his programmed

initiatives. He further orders Raymond to be immune to any pending directives

he may receive by telephone. Only moments later, the phone rings and Shaw, at

last free of this nightmarish spell, nevertheless plays along with the

instructions as given. He is to attend the political rally at Madison Square

and assassinate his stepfather’s competition, thereby allowing Iselin to

deliver a self-aggrandizing speech, expertly timed to sweep him into the White

House. Believing he has avoided the inevitable, Marco leaves Raymond to his own

accord while he hurries to collect Colonel Milt.

But Raymond now appears to have

suffered a relapse, disguising himself as a priest and hurrying to the arena to

carry out his assignment. Frankenheimer convincingly cobbled together this

penultimate confrontation from stock footage of a real convention in progress,

also, footage shot by him at Madison Square Gardens, and, additional close-ups

lensed back in Hollywood. Believing

Raymond is about to kill again, Marco and Milt race about the various corridors

and back stairwells in a desperate search. Too late, Marco discovers a pale

light emanating from one of the upstairs boxes with a bird’s eye view of the

stage. Gun shots ring out. But to everyone’s amazement, Raymond has turned on

Iselin and his mother, killing them both with expert marksmanship before

turning the high-powered rifle on himself. Sometime later, Marco laments Shaw’s

suicide, citing two genuine Medal of Honor recipients for their acts of

selfless valor, marginalizing the fabricated lies that afforded Shaw his place

among these hallowed names.

The Manchurian

Candidate ought to be re-screened theatrically every four years or

so, right around election time, if only because it forever crystalizes, through

the power of popular entertainment, the very real and perpetual threat facing a

free and democratic society, both from without and within. Frankenheimer’s film

is a perennial, chiefly because not all that much has changed in politics since

its time. Politics: it is still the sideshow that believes itself to be the

whole circus. If anything, the scenarios in Condon’s novel, tweaked to

perfection by Axelrod, play as reticent sign posts to our present-age political

landscape reeling perilously out of control. The salvation of a nation, at

least, as depicted in this movie, comes from a morally ambiguous central

character. Raymond Shaw is the dupe, the patsy, the victim and, ostensibly, the

hero of this piece. Lawrence Harvey’s varied performance gives us this spectrum

of conflicted passions. Shaw is so much mor than the emotionally shut off

martinet.

The Manchurian

Candidate was Frankenheimer’s breakout movie. Frankenheimer, then considered a

competent television director before its release, became a leading purveyor of

documentary-styled film-making techniques soon to revolutionize the look of

sixties’ cinema. Initially acquiring the rights with his own money, the project

was brought to Frankenheimer’s attention by George Axelrod; the two slated to

work together on Breakfast at Tiffany’s. In hindsight, it was, of

course, kismet Frank Sinatra’s name should eventually be attached to this

project, as Sinatra’s hobnobbing with the Kennedy clan, and his enthusiasm for

Condon’s book prior to the President’s assassination, brought in the big

investors as only Sinatra’s name on a marquee could. The actor’s initial demand

to cast Lucille Ball as Eleanor left Frankenheimer cold. Together, director and

star decided Angela Lansbury was a better fit. In truth, such convincing boiled

down to Frankenheimer setting a private screening of All Fall Down for

Sinatra, at the end, ebulliently declaring, “That’s the lady!”

By contrast, and in the shadow of

Angela Lansbury’s towering performance as ‘the mother of all mothers’, the

other co-starring female, amiably filled in by doe-eyed Janet Leigh, goes

largely unnoticed, though hardly ignored. Leigh’ subtler Rose Cheney manages the

most of a part otherwise easily devolved into thankless second-string support.

Leigh and Sinatra have genuine and abiding chemistry, flirtatiously sincere and

unexpectedly imbued with an empathetic tenderness. She ‘mothers’ him, but in a

very adult way. It works because, after all, we are talking about Sinatra, an

infallible survivor of his own roller coaster ride, in a career left with many

battle scars from Hollywood’s golden age to prove not only his mettle but

Teflon-coated durability as well. Upon its

debut, The Manchurian Candidate polarized the critics, some citing it as

the most influential and suspenseful political thriller ever made, while others

eagerly pounced on its seemingly fanciful machinations as pure poison, “…the

most vicious attempt yet made to cash in on Soviet-American (Cold War)

tensions.” Today, it remains a

prescient and powerful piece of American cinema. They don’t make movies like

this anymore.

A few years ago, when Kino Lorber

announced it would be pursuing a rather aggressive campaign to bring a lot of

the United Artist deep catalog to ultra-hi-def, I must confess I remained a skeptic.

After all, movies like The Manchurian Candidate had already been given

meticulous consideration on standard Blu-ray. How much better could they

possibly look? But the results herein, and elsewhere, have since spoken for

themselves. For this 4K release, The Manchurian Candidate has been

sourced directly from an original 35mm negative. And wow, are you in for a

treat. The B&W elements sparkle. Age-related artifacts are not a problem.

Contrast is uniformly excellent with deeper, richer black levels that never

obscure fine detail, revealed to the nth degree in every frame.

Close-ups offer startling clarity. The 2.0 DTS mono audio is adequate for this

presentation.

Kino has ported over at least some

of the extras from previous editions released by MGM/UA. Retained, Frankenheimer’s

audio commentary, interviews with Sinatra, Frankenheimer, Angela Lansbury, and,

George Axelrod, plus a reflection piece featuring director, William Friedkin.

We also get a very brief outtake, and an obtuse featurette on ‘how to get shot.’

Last, and least of all, a theatrical trailer. We are missing the Criterion

exclusively produced extras: a reflection from filmmaker, Errol Morris, and

featurette with historian, Susan Carruthers. And no one has been able to ever

secure the rights to the hour-long series: The Directors: John Frankenheimer,

which featured a very intimate portrait and overview of his career and movies,

produced in 2003 and included only on the Arrow region ‘B’ Blu. Bottom line: hang

onto your Criterion for these extras, but indulge in Kino’s 4K for an entirely

revitalized presentation of the movie. Very

highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out

of 5 – 5 being the best)

5+

VIDEO/AUDIO

4.5

EXTRAS

2

Comments