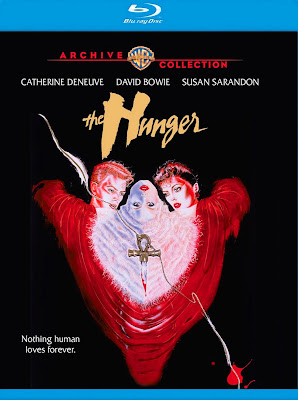

THE HUNGER: Blu-ray (MGM 1983) Warner Archive Collection

An ageless

Catherine Deneuve, underutilized David Bowie and some mildly exotic art house

lesbiana masquerading as incongruous, if occasionally bone-chilling Goth

horror/suspense, are likely the best reasons to indulge in director, Tony

Scott’s The Hunger (1983); a fairly

mindless, if immeasurably stylish excursion into vampirism. Is it just me or is

everyone in this bungled cinematic revamp of Whitley Strieber’s miraculous and

tantalizing novel smoking enough cigarettes to give Philip Morris lung cancer?

Political incorrectness aside, the screenplay by Ivan Davis and Michael Thomas

all but jettisons the novel’s back story, devoted to principled but lonely

sophisticate, Miriam Blaylock; a centuries-old vampire who has seduced scores

of lovers with the promise of immortality. Cleverly, the novel never refers to

Miriam as ‘the undead’. Actually, she’s not. She is very much alive – sustained

on the blood of hapless victims who are attracted as moths to her eternal flame

of peerless porcelain beauty. Refreshingly, Strieber’s incarnation of the

vampire bears little resemblance to the supernatural, exorcised ad nauseam

elsewhere in the lore of the blood-sucker. Nor are they insidiously intent on

destroying mankind with their magical blood-letting powers simply because they

can. Rather, Miriam has evolved from a highly intelligent and secretive

humanoid species, having coexisted alongside our own for as long as time

itself. She feeds her more perverse ‘hunger’ merely to survive, the same way we

must kill and eat other animals to sustain ourselves. Periodically, the feasting results in a

sexual détente as Miriam takes lover(s) first converted to human/vampire

hybrids with a modest exchange of her blood.

One problem –

even immortality has its limitations and expiration dates. The reason, Miriam

is not human. She was born a vampire like her Egyptian mother before her.

Except for the ankh worn about her neck, doubling as a small impaling device

with which to slash open the throats of her unsuspecting victims, and the briefest

of flashbacks, inserted by Tony Scott as part of his penultimate montage, depicting

an Egyptian queen gorging on the bloody entrails of some poor unsuspecting concubine,

no reference is made in the movie to this ancient past, leaving the viewer

wondering exactly what in the hell is going on. Buried somewhere, perhaps in

the Blaylock’s upstairs attic – a billowy-curtained and dove-infested atrium

where this eternal seductress has stored the decomposing remains of every lover

she has ever taken to her bloody bosom - is a pseudo-intellectual social

commentary about contemporary society’s exploitation of each other expressly

for the rank pleasures of the flesh. Alas, Scott’s movie waffles between

endeavoring to be a ‘message picture’, a stylish suspense/thriller, and a gory

horror flick – achieving lasting status as none of these three, either by merit

of its virtues – or vices – depending on one’s point of view. Given its gruesome subject matter, The Hunger remains an un-remarkably

subdued affair, its one saving grace, its style – moodily uninhibited, but

never going beyond the quasi stages of blood-sharing foreplay.

In belated

passing, we acknowledge the epic loss of a truly original artist; perhaps the

last towering figure to emerge on the music scene in the latter half of the

twentieth century and, alas, an under-exposed figure in American movies: David

Bowie, with his angular, almost anorexic bone structure and piercing hypnotic

stare through wounded eyes; a descriptive visage uncannily designed to be loved

by the camera. It bows well for Bowie that he also managed, seemingly with

effortlessness, to move from seismic shifting/gender-bending pop sensation to

credible ‘legitimate’ actor. The notion he could be both must have appeared

unlikely to his critics, despite his early studies in avant-garde theatre and

as a mime under Lindsay Kemp. Indeed, Bowie would prove much in demand in the

movies, appearing as the brutalized POW in Merry

Christmas Mr. Lawrence this same year, desired by the producers of the

James Bond franchise to play the villain, Max Zoran in A View To A Kill (1985)

– a part he declined – and lending his presence, charm and musical stylings to

the popular children’s fantasy, Labyrinth

(1986). Arguably, acting was Bowie’s first love. Unquestionably, it ran a

parallel course with his music career – the more dominant strain of his life’s

work as time wore on. By 1983, Bowie had already appeared in numerous

theatrical and TV productions in both the U.K. and U.S. Yet, it is in The Hunger that he first emerges a

full-fledged star, despite Tony Scott’s varying misshapen attempts for him to

remain the film’s ‘best kept secret’; briefly glimpsed in his prime, before

being plastered over in Antony Clavet’s stipple and latex appliances that

effectively transform Bowie’s youth into a rapidly gnarling mess of human decay.

Regrettably,

as John Blaylock, the victimized boy toy/vampire-human hybrid, Bowie is given

only a few choice scenes in which to distinguish his acting abilities. This, he

effectively does; particularly in the silently played moments John suddenly

realizes the accelerated and irreversible aging process has already begun; his

hastened physical decrepitude causing him to frantically seek out Dr. Sarah

Roberts (Susan Sarandon) who, understandably, does not believe this jowly and

balding gentleman is actually a man in his mid-thirties, or rather,

mid-thirties plus 200 years. Promising

to address his concerns in less than fifteen minutes, Sarah instead quietly

dismisses John as a crank, forgetting all about him for several hours during which

he continues his rapid decline. Understandably shaken by his metamorphic

transformation, Sarah endeavors to make a mends for her rudeness. But John is insolent

as he storms out of her clinic, hurrying back to the brownstone he shares with

Miriam. In a last ditch and very desperate attempt to stave off his disease,

John murders Alice Cavender (Beth Ehlers), the child protégée violinist who has

come to practice her craft with the Blaylocks. She is unsuspecting this fate at

first, and quite unable to recognize John in his present condition. John drinks

of her blood. But even this does nothing to halt the aging process. John

disposes of Alice’s body in the basement furnace and later in the evening, when

Miriam returns, confesses to the murder.

But his pleas

for Miriam to love him as before are shattered when she, repulsed by his

disfigurement, retires John instead to a storage box in the attic – the cruel

final resting place housing all of Miriam’s moldering lovers; rotting and

skeletal, but still very much – if barely - alive. Not long thereafter, Miriam

is visited by Lieutenant Allegrezza (Dan Hedaya) who is investigating Alice’s

disappearance. She is cagily smooth and mostly successful at dissuading

Allegrezza from discovering the truth. But Miriam is now attracted to Sarah who

has managed to track John down in the hopes of making a formal apology for her

earlier arrogance. Miriam lies to Sarah about John having gone away to

Switzerland, presumably for treatment. Sarah is understandably perplexed, but

accepts Miriam at face value. The two establish an unsettling friendship.

Having earlier quarreled with her own lover, Tom Haver (Cliff de Young), Sarah

falls prey to Miriam’s hypnotic sway, dissolving into a steamy lesbian

seduction. Drawing blood during their love-making, Miriam allows Sarah to

return to Tom. But Sarah fast begins to suffer from inexplicable cramps, night

sweats and convulsions. Colleagues at her clinic analyze a sample of her blood

only to discover two unique strains of plasma within her fighting for

dominance.

Miriam’s

psychic persuasion draws Sarah back to the townhouse where her uncontrollable

compulsion and blood-lust are exercised upon an unsuspecting Tom who has

followed her there. Having destroyed her human lover, Sarah now elects to take

her own life, stabbing herself in the neck with Miriam’s ankh. Afterward, Miriam

dutifully carries Sarah’s seemingly lifeless body to the attic. But she is

unprepared for what happens next; surrounded by the mummified corpses of her entourage

of former lovers, Miriam is hastened over the edge of the upstairs bannister.

Plummeting several stories, her crushed body strikes the marble tile far below

with a thud, resulting in her rapid decomposition. A short while later,

Allegrezza returns to the Blaylock house, only to discover it emptied of its fine

furnishings; a local realtor, Arthur Jelinek (Shane Rimmer), explaining the

owners are since deceased and the proceeds from the sale bequeathed to a

mysterious research clinic. We flash ahead to London. Sarah has not died, but

rather, been transformed by Miriam into a human/vampire hybrid; having

recreated the same moneyed and self-imposed exile with a pair of youths as her

concubines. As Sarah stares blankly off into the distance from the balcony of

her fashionable apartment, Miriam – still very much alive – is heard softly

crying from her imprisonment inside another box concealed somewhere in the

bowels of the building; Sarah, thus doomed to perpetuate the cycle of vampirism

for a good many years yet to follow.

Despite this

penultimate and briefly delicious revenge scenario, The Hunger is not terribly prepossessing. In spots, it downright

drags with very little to say about Whitley Strieber’s infinitely more complex

characters. The novel’s strength was it treated Miriam’s vampirism as grand

tragedy; a quagmire of abject loneliness and highly personal regrets amplified

by the sudden demise of her most recent husband, John. Miriam cannot help

herself, you see. She is not spiteful in her bloodlust. It is a necessity for

her survival. The movie suffers two great miscalculations; first, by ignoring

Miriam’s increasing inner conflict about killing for the sake of self-preservation,

and second, because the Davis/Thomas screenplay treats Miriam’s personal loss

and John’s eternal suffrage, not as pivotal moments of realization (as in the

novel) rather, vignettes in a more vast canvass of doomed eternity; director,

Tony Scott far more interested in indulging in a bit of art house soft core,

punctuated by Act 2, No. 2 Duetto, Viens,

Malika... Sous le dôme

épais où le blanc jasmin, from Léo Delibes’

Lakmé: The Flower Duet. Scott’s forte, as with his more famous brother,

Ridley, is impeccably staged compositions, dimly-lit, smoky interiors that

positively reek of embalming fluid in all their sophisticated claustrophobia.

The Hunger is a very dark movie, figuratively and literally;

thanks to Stephen Goldblatt’s morose cinematography. This ‘look’ works well for

the interiors of the Blaylock manor – a fashionable New York brownstone; also,

ably setting the overall tone during the film’s stunning opener under the main

titles; a caged nightclub subbing in for an uber-Faustian purgatory where

misguided humans, who think themselves creatures of the night, bump and grind

to the erotic strains of Bauhaus’ anthem, ‘Bela

Lugosi’s Dead’. But it remains a mystery – and a disconnect – to discover

the rest of Manhattan – and later, London – having adopted this visual

equivalent; the clinic where Sarah experiments on antisocial baboons to probe

the secrets of life (just call her Madame Frankenstein) as dank, dim and

depressing; bathed in a silty and perpetually lingering fog in the air. The Hunger’s strength is its palpable

chemistry between Catherine Deneuve and David Bowie; Deneuve’s doe-eyed

seductress taking on the vogueish characterization of Sean Young’s replicant,

Rachel, from Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner

(1982), and Bowie, in his youthful incarnation, very much playing to the

perversions of a steely-eyed pleasure seeker time has almost forgotten but

regrettably, is about to recall home with disastrous results. There is merit to

this coupling, rather unceremoniously dispatched by Tony Scott in just a few

key scenes, utterly deprived of the novel’s back story to make John’s loss, and

Miriam’s tear-stained reaction to it either compelling or, in fact, memorable.

The picture’s

‘art house’ quality is capped off by its extended lesbian sex scene; Sarandon,

naked from the waste up, and, Deneuve, cinched into a black bustier, fondling

one another with wet, open-mouthed kisses; most of it photographed through

billowy gauze curtains to modulate the more overtly pornographic elements. Aside:

I, for one, am not particularly a fan of sex in the movies. While the act

itself can undeniably manifest pleasure between two people in private, the

intrusion of a camera strips bare these shared intimacies, simultaneously

ignoring the cerebral aspects of heartfelt love-making, substituted by a

gratuitous placements of hands, arms and legs in service to the staging of the

act, yet, oddly enough, neither to titillate nor tantalize with the promise of

genuine erotica, but rather, make commonplace and crude such experimentation between consenting adults. The blood-letting aspect of The Hunger’s sexual liaison does not shock or repulse as much as it

appears almost anticipated. It neither advances the narrative nor does it prove

any point that has not already been given more graphic illustration elsewhere

in the plot. As such, what purpose it actually serves other than to create a

moment of ‘oh, God…I can’t believe they

did that’ is, frankly, beyond yours truly.

From the

vantage of our present sex-saturated culture, The Hunger will likely appear tame, with conventional ‘critique’ and what passes for

intellectual ‘wisdom’ these days

slanting toward ‘so, what’s the big

deal?’ – a very sad indictment on this generation’s inability to discover

or even be able to acknowledge something – anything – that is

sacred, or even deemed worth preserving without first adopting a cynical ‘in your face’ attitude and disregard for

human frailty of any kind that does not completely transfer into ridiculous

farce. As a product of the 1970s, coming of age in the 1980s, I can only

suggest the obvious to those who neither experienced this gradual devolution

first hand, nor fear the ‘looking glass’

flipside in moral iniquity yet to completely devour our one-time ensconced

system of values, currently caught in the death throws of an absolute societal

implosion. We are very near this tipping

point; the anarchy of our art – pre-sold as Godless and gutless ‘truths,’

presumably self-evident, supplanting and marking the end of a beautiful way of

looking at the world. The Hunger is

hardly ‘high art’ or even born of an

aspiration to situate itself into high culture, though, at the very least, it

aspires to cast its unflattering pall on the foibles of the latter, circa 1983.

Our more recent spate of horror movies have, with increasing frequency, make

not even an attempt to sheath their menial drivel with odes to the artistic;

something Tony Scott endeavored – and occasionally, succeeds – in doing.

Streiber’s

novel took the high road, exploring aspects of human passion and tenderness, seen

through the ultimate in flawed relationships, exploring our collective fear of

the aging process and its correlated loss of sexual desire; better still,

employing the arc of history, ingeniously blended with his own reworking of

classic European folklore devoted to vampirism.

The movie is not nearly as clever, but it still manages to find

something more to say about a few of these eccentricities before and after

Miriam and Sarah have shed their inhibitions and their clothes. In retrospect,

even Scott’s mangled effort becomes unanticipatedly commendable. What manages to seep into the film, perhaps

even in spite of itself, is a glint of Streiber’s more powerful

intellectualism; an almost shockingly clinical deconstruction of these

aforementioned influences and appropriately centered around Miriam Blaylock:

woman as creature of the night, empathetic in her innate – if bizarrely human –

longing to belong to someone, denied even this by the natural world’s inability

to chart a share path for her eternity.

The novel used

epigrams from Keats and Tennyson to argue its points. The film, merely takes in

some badly bungled pseudo-psychological babble about misguided unions and the

wreck and ruin they can bring to those unsuspecting of a deeper, otherworldly

and exacerbated ‘hunger’ for something greater than self-preservation or a

momentary tussle between silken bedsheets. Streiber’s novel drew parallels between human

love and animal prey. Tony Scott tries to straddle these commonalities; much

top clumsily to make them stick as anything better than brief and fairly

grotesque moments of foreshadowing; as the scene where an adult male baboon in

Sarah’s research laboratory slashed into its female companion until she is

thoroughly disemboweled. As literature, The

Hunger was both a page-turner and illuminating exposé on humanity’s shared

imperfections and its inhumanity towards professed loved ones. Cinematically,

such intricacies get distilled into a dark (really dark) journey through the

labyrinth of genuine human pain; void of Streiber’s restlessly ambitious

intelligence and ability to probe and deconstruction the secrets of our

occasionally wanton and malignant universe. The movie merely presents us with visions

of a hopeless future for Sarah – now the blood-sharing priestess of this doomed

legacy; destined to remain alone, isolated, and ravaged by the gnawing

realization there can be no refuge for the wicked; at least, none to satisfy

beyond the most base quest for survival, and yet, without promise, hope or even

a fixed sense of one’s own mortality – thus, depriving her of even a momentary

sense of permanency in this corruptible world.

The Hunger was shot by British cinematographer, Stephen Goldblatt.

The Warner Archive’s new 2K transfer is culled from an interpositive, color

corrected to address issues of fading. The Blu-ray is, for the most part, quite

stunning with only a few scattered incidents of image instability. Blu-ray's

ability to glean even the minutest detail from Goldblatt’s subtle variations,

lensed under deliberately under-lit conditions, is quite striking. The image adopts a chronic azure hue with

exaggerated uber-vibrant reds and golds as its sparsely shared primary colors.

Contrast is superb throughout and grain structure has been lovingly preserved,

shown off to its best advantage. Bottom line: as with all catalog Blu-ray

coming down the WAC pipeline, The Hunger

will surely not disappoint. The film’s original mono audio gets a breathtaking

2.0 DTS mono upgrade. Fidelity is shockingly solid and effective. The only

extra is an audio commentary from Tony Scott, actually quite comprehensive and

easily one of the best I have heard in a very long while. Here is a director so

secure in his craft and ability to keep us spellbound in the dark, he can

effortlessly veer from commenting directly on the action taking place on the

screen to offer back story, insight and anecdotal stories about the making of

the movie that, at times, I sincerely found a far more enriching experience

than the movie itself. Bottom line: if vampires are your cup of tea, The Hunger comes across as a classier

affair than most. It’s still pulp movie-making rather than cinéma vérité, but

it effectively bests almost anything passing for a good scary vampire flick

these days. Bottom line: recommended with caveats.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

3

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

1

Comments