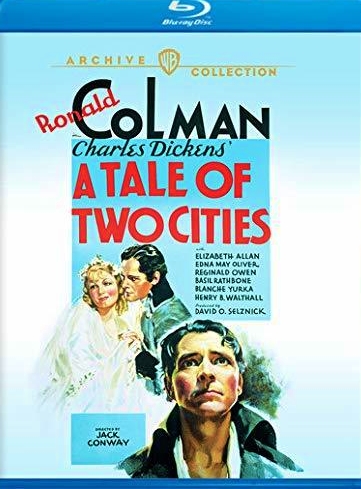

A TALE OF TWO CITIES: Blu-ray (MGM, 1935) Warner Archive

A moment’s pause – reverence, actually, to honor a

real/reel ‘Jack’ of all trades: Hugh Ryan Conway – better known in and out of

the Hollywood community as Jack Conway, who began his career as a repertory

theater actor, fresh out of high school. At the dawn of American cinema - 1911,

to be exact - Conway became a member of D.W. Griffith's stock company as an

actor; four fast years later, to segue into the director’s chair – first at

Universal (1916–17 and 1921–23), then at MGM in 1925, where he would remain for

the next 25 years, often to helm the studio’s most prestigious all-star

pictures – Tarzan and His Mate, and, Viva Villa! (both in1934), Libeled

Lady (1936), Saratoga (1937), A Yank at Oxford (1938), Boom

Town (1940), Honky Tonk (1941), and, The Hucksters (1947) among

them. As a director, Conway today is neither

revered nor even regarded as much of anything beyond a very competent ‘company

man’ who could deliver the goods on time and on budget without affecting an

auteurist sense of personal style. Personally, I find this sort of assessment

of his skillset rather insulting. If Conway’s movies lack the personal imprint - of say, a Hitchcock or Cukor - a notion I also take umbrage to, then they

nevertheless collectively reflect upon an elegance and erudite wit, more than capable

at understanding the scene and the placement of the camera, with exceptional proficiency at achieving the very best for the stars who appeared

in these movies. Conway worked with the greatest of the studio’s legendary

talents – Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy, Claudette Colbert, Robert Taylor, Vivien

Leigh, Ronald Colman, Jean Harlow…and on and on. So, it stands to reason, none

of these A-listers would have been entrusted in his care, lest studio raja, L.B.

Mayer believed Conway possessed his own A-list abilities to get the proverbial ‘show’

on the road, do it big, and give it class. And Conway, along with Metro’s

Edmund Goulding, holds the dubious distinction of having directed the most Best

Picture-nominees (3 total – Viva Villa!, Libeled Lady and 1935’s A

Tale of Two Cities…albeit, without ever receiving a nod as Best Director). In

1948, seemingly at the height of his career, Conway retired from

picture-making, dying of pulmonary disease a scant 4 years later.

Astonishing, but even as I begin to formulate my

thoughts on MGM’s lavishly appointed production of Charles Dickens’ A Tale

of Two Cities, I can almost hear its star, Ronald Colman’s mellifluous and

cultured cynic, Sydney Carton hypothesizing, “It's a far, far better thing I

do than I have ever done. It's a far, far better rest I go to than I have ever

known.” Indeed, the film’s producer, David O. Selznick could have done with

just such a respite, having bounced around the studio circuit after the death

of his father, with trend-setting, though equally as problematic stints as an

executive at Paramount and RKO. By the time Selznick elected to produce A

Tale of Two Cities at MGM he had already been on the Metro back lot once

before, ousted for his outspokenness by VP in Charge of Production, Irving

Thalberg. That was in 1929. Two years later, Thalberg, whose autonomy during

the early silent era had made Metro the envy of Hollywood, suffered the first

in a series of near-fatal heart attacks after returning home from the

star-studded premiere of his latest passion project, Grand Hotel (1932).

During his convalescence, Mayer went over Thalberg’s head, appealing to Loew’s

Incorporated President, Nicholas Schenck to draw up a new agreement, one to

effectively splinter Thalberg’s autonomy and create a producer-heavy system

with men loyal principally to Mayer – making Mayer the undisputed monarch of

all he surveyed.

In the beginning, Mayer had not harbored such

animosity towards Thalberg. In fact, he

had backed his young Vice President against any encroaching dissent. And why

not? Thalberg’s uncanny knack for picking winners had put MGM on the map.

However, increasingly, Thalberg’s ambitions knew no master. According his own

likes, Thalberg was going to do it better, do it bigger and give it even more

class than virtually all the other studios combined. He would spend whatever it

took to shoot and re-shoot a picture until it was just right – or as near to

that mind’s eye perfection as his artisans could achieve. By the early 1930’s,

Thalberg had elevated the company’s prestige, decidedly in ways that did not

entirely appeal to Mayer. Their philosophies diverged on a single point:

Thalberg, endeavoring to make fewer pictures per annum but at a premium that

would draw in even bigger audiences while Mayer wanted to keep up the breakneck

pace of making and releasing one studio feature each and every week. Mayer

reasoned Thalberg’s go-for-broke mentality was far too gauche and risky,

especially given the nation’s recent plummet into the Great Depression. As

such, Mayer readily feared Thalberg’s monies spent would not equate to monies

earned. Despite this growing chasm in their artistic differences, Metro

continued to produce the sorts of entertainments both men could take

considerable personal pride. But now, with Schenck’s complicity, Mayer had

effectively taken over. In the ‘new’ contract, Thalberg was taken down a peg,

no longer VP of the whole menagerie, but manning his own division within the

parameters of Mayer’s authority. At the same time, Mayer wasted nothing to

bring in fresh blood to reinvigorate and fill in the gaps – stalwart

producers/directors like Howard Hawks and David O. Selznick – men owing their

allegiance to him – and collectively nicknamed Mayer’s ‘college of

cardinals’.

It ought to be noted, first, that Metro functioned

implicitly, and by design, on an ‘art by committee’ approach to making movies

a trickling down of the creative juices for which Selznick had very little use.

Thus, Selznick’s first dry run at MGM had been mired by interference on all

sides. His second bite at the apple, after leaving Paramount and RKO, would

afford him the kind of autonomy Thalberg had enjoyed before his heart attack, a

chance for Selznick to practically be his own boss – if, with the slightest

consideration given Mayer, who also happened to be his father-in-law. In

reference to Hemingway - and Hollywood nepotism run amuck – Selznick quickly

became a joke around the back lot - “the son-in-law also rises”. It was

too much indignation for Selznick to take sitting down, and he could never

quite forget or forgive the begrudging considerations afforded him. Perhaps to

prove anything Thalberg had done he could do even better – or, just as well –

Selznick wasted no time assembling an all-star dramedy along the lines of Grand

Hotel; the exuberant, Dinner At Eight (1933). Since then, Selznick’s

pursuit of perfection had yielded several masterpieces, including Dancing

Lady (the musical that introduced Fred Astaire to moviegoers and revived

Joan Crawford’s sagging career), Viva Villa!, a definitive adaptation of

David Copperfield, and likewise, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (both

made and release in 1935); Selznick, now considered something of the éminence

grise for literary adaptations - a sub-genre that had great appeal for

Thalberg.

Given all the luxuries afforded it, A Tale of Two

Cities really ought to have been a much better picture. Without question,

it began life as a far lengthier one, almost three-hours when sneak-peeked at

Long Beach to, as Selznick later recalled, “an audience of rowdy sailors and

their dates.” From the outset, Selznick had campaigned to secure Ronald

Colman for the part of Sydney Carton, a role tailor-made for the Brit-born

superstar. Too bad, in the interim, Selznick once more began to encounter

needling opposition, objections about hiring Jack Conway to direct and

grumblings from his Director of Photography, Oliver Marsh over the staging of

one of Colman’s lesser soliloquies Selznick wanted shot entirely for mood, lit

only by candlelight. “Every scene was a problem,” Marsh later mused, “…we

got it by using a faster film and opening up the aperture all the way…but the

most difficult scenes were in Defarge’s wine shop, shooting through real

windows to capture action taking place both inside and out simultaneously.” Despite

Selznick’s fastidiousness, the production moved along at a fairly inspired clip

and without incident. For authenticity, Selznick hired Val Lewton to provide

research and coverage on the climactic storming of the Bastille.

Yet, in hindsight, what the picture would come to lack

was continuity in Selznick’s usual unwavering tenacity to micromanage every

last facet of its production. During the aforementioned Bastille deluge, as

example, it is rather noticeable a handful of extras, costumed as women, are

actually burly male stunt doubles, with two reused yet again as stand-ins

during the brutal confrontation between Miss Pross (Edna May Oliver) and Madame

Therese De Farge (the extraordinary, Blanche Yurka). At some point, Selznick

simply gave in, antsy and understandably preoccupied with his anticipated move

into the old Thomas Ince Studios, soon to become Selznick International’s

headquarters, only a stone’s throw from Culver City’s front gates. Perhaps

Selznick had had enough in what he likely perceived as the willful sabotage of

his best endeavors to elevate the overall prestige of the picture-making biz

from the inside. Mayer would not have agreed, although Thalberg may have, if

only Selznick had not burned his bridges there a decade earlier. Thus, as A

Tale of Two Cities neared completion, Selznick elected to go over both

men’s heads and rattle off a rather scathing memo to Nicholas Schenck about

Metro’s lack of publicity – or rather, the kind of publicity he, Selznick,

would have wished to precede the general release of his swan song.

If only Selznick had chosen a more diplomatic

recourse, even to simply address his woes to Schenck directly, he might have

garnered a few browning points. But Selznick had the chutzpah to carbon-copy

his memorandum to virtually every executive he felt had besmirched him during

his brief stay. Of these, Metro’s PR man, Howard Dietz, took great exception

upon reading the accusations and almost immediately firing off his own

rebuttal, while carbon-copying Schenck and virtually all the execs who had been

sent the previous address by Selznick, topped off with “You remind me of the

bisexual Marquis who, when asked which he prefers – men or women – replies, ‘I

like them both, but there ought to be something better!’” Selznick’s blood was brought to a boil. But

he was to receive an even greater, if as unexpected admonishment as his

sendoff, this time from Schenck. Forced to take sides, Schenck stood behind

Dietz. In his memo to Selznick, Schenck accused Selznick of lacking humility

and gratitude for the time and luxuries he had been afforded while at MGM.

Schenck also suggested Selznick had enjoyed something of a ‘free ride’ and had

been spoiled to simply expect he could demand more of whatever he wanted

without question. Schenck’s memo concluded by assuring Selznick he could not.

Thus, A Tale of Two Cities hit theaters with

very little fanfare at the tail end of 1935. And although it was well-received

by the public and critics, for Selznick, it was something of the colossal thud

to mark exit from MGM. In more recent times, the picture’s reputation has been as

blunted by rumors of what it might have been, or rather, had been before all

the cuts were made after the first prevue. Indeed, topping out at three-hours, A

Tale of Two Cities might well have possessed that spark of true genius for

which a goodly sum of Selznick period pictures today are justly celebrated; a

Dickensian epic of unimpeachable scope. The storming of the Bastille, with its

thousands of extras flooding Metro’s back lot Ruritanian streets, charging up

the drawbridge, pitchforks in hand, and shot from a very high angle, perhaps,

even foreshadows the approach Selznick would choose as Scarlett O’Hara arrives

at the railroad depot in Gone With the Wind (1939) to survey the

mind-numbing casualties littering its stockyards. And Selznick ends A Tale of Two Cities

on a no less mind-boggling sequence - jeering crowds, crammed by the hundreds

into that backlot Parisian square, superbly framed by some convincing matte

work, the rabble gathered to witness the beheading of the aristocracy, the

razor-sharp chop of the guillotine, juxtaposed with the wistful camaraderie

between a wrongly accused seamstress (Isabel Jewell) and Colman’s magnanimous

Sydney Carton, successfully traded as the sacrificial lamb for Charles Darney,

nee - Evrémonde (Donald Woods).

Alas, at exactly a minute over two hours, the

theatrical cut of A Tale of Two Cities somehow lacks emphasis on its

story-telling. Instead, it devolves into a series of highly theatrical

vignettes, the screenplay by W.P. Lipscomb and S.N. Behrman drawing not only

from Dickens, but Thomas Carlyle’s The French Revolution, M. Cléry’s Journal

of the Temple, and, Mademoiselle des Écherolles’ and M. Nicholas’ The

Memoirs; suffering from the gout of history at the expense of solid

character development. Viewed today, the

picture unquestionably has its virtues, beginning – and practically ending –

with Ronald Colman’s supremely edifying performance. Part, if not all of

Colman’s screen appeal is to be unearthed in the subtleties of his intonation,

shifting from callous disregard to a profound compassion for humanity almost in

a single sentence, his second to last moment, affectionately shared with the

seamstress, reeking of bittersweet self-discovery for the man he might

otherwise have become.

The other great performance is owed to Blanche Yurka,

an insidious and vindictive Madame De Farge. While Colman’s reputation has

managed, mercifully, to weather the sands of time, Yurka’s today is, alas,

largely forgotten, a consummate pro, repeatedly typecast as stern, middle-aged

frumps, occasionally possessing clear-eyed compassion to rival her intimidating

doggedness. There are flashes of Yurka’s beginnings as a talented opera singer

in her Madame De Farge, a weighted theatricality with a tinge of Victor Hugo’s Les

Miserables as she menaces from the pulpit, championing Darney’s public

execution as vengeance for the crimes perpetuated upon her family by his uncle,

Marquis St. Evrémonde (Basil Rathbone). Indeed, A Tale of Two Cities

would have been a ‘far, far’ more exquisite piece of cinema if all – or

any – of the others in the picture rivaled either Colman’s or Yurka’s potency

in a scene. Yet, despite some very competent contract players assigned this task,

virtually all are forgettable. The worst of the lot are the romantic leads -

Donald Wood and Elizabeth Allen – fresh faces entirely lacking in any

intangible star quality. Basil Rathbone is a formidable baddie, but offed much

too soon. Reginald Owen is his usual comic relief as solicitor, C.J. Stryver,

seemingly inept at the law and lost without Carton’s influence. Billy Bevan is

a rather amusedly befuddled schemer. But Henry B. Walthrall and H.B. Warner are

utterly wasted as the sages of the piece, Dr. Manette and Darney’s tutor,

Gabelle respectively.

A Tale of Two Cities begins with inserted text torn

directly from Dickens’ prose. “It was the best of times…it was the worst of

times…” and so on and so forth. The device of book-ending a celluloid

adaptation of a great novel was nothing new. Arguably, by 1935, it was a rather

foregone part of the program. Yet increasingly, A Tale of Two Cities

relies on titles not from Dickens to cover large gaps in the narrative

timeline. Presumably, these were added in after Selznick made his cuts to the

3-hour prevue version. Alas, they are unevenly interspersed and take the

audience out of the story, drawing their attention to the fact whole portions

of the book’s plot seem to be missing. Selznick gives us the Cole’s Notes

treatment of Dickens instead. From this inauspicious beginning, we regress to

an inn somewhere in England where Mr. Jarvis Lorry Jr. (Claude Gillingwater) of

Tellson’s Bank is about to inform Lucy Manette (Elizabeth Allen) that her

father, presumed dead, is still very much alive and newly released from

eighteen years in the Bastille, presently in the care of Madame and Ernest De

Farge (Mitchell Lewis). Naturally, this news comes as something of a shock to

Lucy, who, along with Lorry and her servant, Miss Pross, immediately sets sail

for France to be reunited.

The De Farge’s manage a wine shop, quietly overseeing

and promoting the groundswell of public animosity shared by the rabble against

the aristocracy. Who can really blame them, with abominable examples like the

Marquis St. Evrémonde, instructing his coachman to irresponsibly race through

the cluttered streets, resulting in the death of a young boy, trampled beneath

the galloping hooves of his horses?

Evrémonde is unmoved, collectively chastising the rabble as being

irresponsible parents. Upon returning to his estate, the Marquis discovers his

nephew Charles, already packed and preparing to leave. Evidently, the young

Evrémonde does not share his uncle’s views, either of the people or the

critical situation fast enveloping France with mounting dissention towards its

‘artisos’. It will take a revolution for the Marquis to see things more

clearly. Changing his name to Darney, Charles admonishes his uncle for abusing

his privileges. Evrémonde is jealous,

conspiring with a servant, Morveau (John Davidson) to hatch a plot. A staged

event will result in Charles’ arrest just as soon as his boat docks in England.

Crossing the Channel, Charles and Lucy become

acquainted under Lorry’s watchful eye. Charles is obviously smitten and takes

certain liberties to procure an invitation to the Manettes. Alas, barely on

English soil, an incident is staged by Barsad (Walter Catlett), a conspirator

loyal to the Marquis. Charles is immediately arrested and C.J. Stryvers is

hired to defend the case. But Stryvers is a bumbler at best. Mercifully, his

underling, Sydney Carton possesses a keen mind and a streak of his own petty

larceny to overcome the seemingly insurmountable evidence amassed against their

client. Cornering Barsad in a presumably ‘friendly’ drinking game, Sydney

gleans a confession from his lips, later used to discredit his testimony at

trial. The charges against Charles are dismissed, leaving him free to pursue

Lucy, whose faith in Charles has never waned. Charles feels it his duty to

confess his true identity to Dr. Manette, almost certain that in doing so he

will wreck his romantic chances with Lucy. But Charles has underestimated the

doctor’s ability to forgive his enemies – particularly, since Charles has disavowed

virtually any familial association with his uncle. Sydney is queerly moved by

Lucy’s tenderness, even more so after she invites him to dinner, encouraging a

friendship Sydney discovers to be most rewarding. It can never be love, as

Lucy’s heart belongs to Charles and vice versa. The two are eventually married

and have a child, also named Lucie (Fay Chaldecott), whom Sydney comes to

adore.

Back in France, the Marquis is murdered by the father

of the child he road down in the streets.

News of this avenged killing spreads far and wide. Revolution breaks out in

France. The Bastille is stormed, defended at cannon point by the King’s Guard.

Just when it looks as though the revolutionaries shall lose, the militia

arrives – not to break up their rioting, but rather partake with muskets aimed toward

the cause of freedom and liberty. The monarchy is toppled and anarchy sweeps

Paris. Now, the guillotine regularly lops off the heads of members of the

aristocracy, but also anyone who dares oppose this reign of terror, cruelly

managed by Madame De Farge. Charles’ former tutor, Gabelle, is taken hostage

and made by De Farge to sign a false letter begging Charles’ return to testify

on his behalf. Deviously, De Farge has no intent of letting Gabelle live once

his signature has been committed to paper. Gabelle is knifed and the letter

sent. Instead, De Farge is determined Charles should be beheaded to satisfy her

crafty abhorrence to see every last Evrémonde destroyed.

Charles naively returns to France and is almost

immediately arrested and imprisoned. Learning of his incarceration, Doctor

Manette and Lucy, Sydney and Miss Pross rush to attend Charles’ trial. Yet,

this proves to be a mockery of justice. Doctor Manette appeals to the rabble to

spare Charles’ life. Surely, he would not have given his consent for his only

daughter to marry an Evrémonde if the venom of the Marquis, responsible for his

own imprisonment in the Bastille, ran through Charles’ veins. Esteemed by the

masses, the doctor’s testimony is taken at face value. But now, Madame De Farge

takes to the pulpit, decrying Manette as a feeble old man who has lost his way

to see justice served. De Farge wants blood spilled for her mother, father and

the sibling all murdered by the Marquis. She challenges the court to reconsider

how many lives the Evrémondes have destroyed, and demands the satisfaction of

seeing their entirely bloodline wiped out. Stirred by her vindictive

muckraking, the people elect Charles Darney must die. Having miserably failed

to prove his son-in-law’s innocence, Dr. Manette begins to lose his grip on

reality, regressing into memories of his own tortured years of imprisonment in

the Bastille. The next afternoon, Lucy naively attends De Farge at her wine

shop with her daughter in tow, pleading for Charles’ life but to no avail.

Later, De Farge plots to have Lucy and the child killed. Wisely recognizing her

error in judgement, Sydney encourages Lucy to take the girl and leave Paris at

once. He shall remain behind and attend to matters.

Unable to see any other way out of this impossible

situation, Sydney elects to be smuggled into the Bastille the night before

Charles’ execution. Knowing he would never agree to this bait and switch,

Sydney chloroforms Charles, employing Barsad to escort him to safety while he

remains behind in Charles’ cell. On the day of his public execution, Charles is

already on the outskirts of Paris. Meanwhile, Miss Pross makes ready to leave

the city with Lucy, Mr. Lorry and the couple’s young daughter in tow.

Determined they should all come to an untimely end, Madame De Farge sneaks into

the house with a small musket pistol hidden beneath her skirts. Intercepting

the vial woman, Miss Pross bars De Farge’s way, wrestling her to the ground. De

Farge and Pross continue to struggle for the gun until it goes off, killing De

Farge. Meanwhile, Sydney comes face to face with a seamstress accused of

loyalist sympathies to the aristocracy. The poor girl is innocent, but wild

with fear. Knowing the Manettes well, she immediately recognizes that the man

pretending to be Charles is somebody else. The girl relies on Sydney to comfort

her and, in a relatively brief time he manages to inculcate a sense of calm

from within. The girl is grateful and marches valiantly to her death, Sydney,

immediately following on the steps of the guillotine. As the blade is raised hirer

and hirer along its scaffold, Sydney hypothesizes Dickens’ immortal line: “It's

a far, far better thing I do than I have ever done. It's a far, far better rest

I go to than I have ever known”; the camera panning upward, sparing us the

grotesqueness of these atrocities already committed, and the one about to take

place.

This penultimate sacrifice made by Sydney Carton

should have ended A Tale of Two Cities. Alas Selznick, as though to gild

the lily, and, quite unable to leave well enough along, has added a Biblical

quotation from John 11:25 - “I am the Resurrection and the Life: He who

believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live.” The quote is fitting, and yet, somehow pushes

the poignancy of the moment over the top, now, overwrought and lacking the

subterfuge for which other Selznick period costume dramas - most notably, David

Copperfield (1935) - remain justly celebrated. Thus, and only in hindsight,

the best moment in A Tale of Two Cities remains the storming of the

Bastille - a tour de force in staged action, orchestrated with all the prestige

MGM at its zenith can afford. It is the colossal spirit of the moment that

proves infectious. To be certain, there are elements also to be gleaned from

Blanche Yurka’s hell fire and brimstone admonishment, determined to condemn an

innocent man to death, or better still, in the near lyrical affliction of

self-sacrifice as Colman’s Carton bids a silent farewell to this godless world;

also, the meaningless life he has snuffed from it, now to be taken back from

him. Colman’s reactions to the crowd’s hot-blooded sport of beheading are as

unfathomable as the headless remains piled up somewhere off camera, his Carton,

stoically surveying this bloodthirsty audience with sad-eyed clarity. He might

indeed believe in that ‘far, far better rest than (he) has ever known’,

as the world now to envelope is hardly a fine place with virtues worth

preserving.

If only the other scripted episodes in the picture had

lived up to these, or at least been acted with as much artful competency, this A

Tale of Two Cities might have long since entered the annals as the

definitive version. Certainly, it

remains without peer for its handling of Carton’s execution. To be sure, there

have been remakes, virtually all of them approaching the material much too on

the nose to thoroughly satisfy. Colman’s Carton is both magnanimous and

sobering as he steps before the scaffold. His performance has depth of

character to recommend it, and class, and, of course, that honeyed and dreamy

voice to make Dickens’ prose leap off the screen more emotionally satisfying

still as great cinema. Whatever emotional

heft it otherwise lacks, for these brief glimpses into Sydney Carton’s

surrendered and self-sacrificing soul, once seen, are never to be expunged from

the consciousness. Even so, A Tale of Two Cities is still not a great

movie. But it is a highly enjoyable, and occasionally compelling, one.

The Warner Archive’s new-to-Blu is another instance of

a movie that merely looked adequate on DVD but now advances to a level of visual

resplendence arguably always there, yet buried beneath decades of neglect and

shortsightedness in video mastering efforts. The Blu-ray exhibits a quantum advance

in virtually every department. The grey scale is gorgeous, with subtleties

detected in hair, skin and clothing. Contrast,

to have appeared boosted on the DVD, now has been brought back into perfect

register. Whites are clean, but not washed out, and blacks are deep, rich,

velvety and solid. A handful of shots exhibit some minor softness, likely

culled from dupes or other less than stellar archived materials. In any case,

age-related artifacts have been expunged for an image that is naturally smooth

and delicious. The 2.0 DTS mono has eradicated the hiss and pops that were a

part of the old DVD release. Three

shorts that once accompanied the DVD – Audioscopiks, Hey-Hey Fever, and Honeyland,

have all been ported over, albeit with zero upgrades to their image quality. We

also get the Lux radio adaptation, also starring Colman. Bottom line: A Tale

of Two Cities is a movie that – despite some pitfalls – deserves to be seen

again and again. The highlights outweigh the shortcomings, and WAC’s new

Blu-ray ensures everything is looking very spiffy indeed. Highly recommended!

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

4.5

EXTRAS

1

Comments