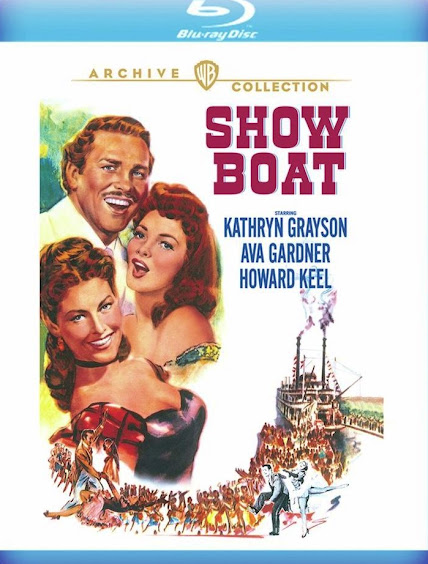

SHOW BOAT: Blu-ray (MGM, 1951) Warner Archive

By Spring of 1950, MGM producer, Arthur Freed was

sitting pretty at the most profitable movie studio in the world. Freed,

arguably the greatest proponent the movie musical has ever known, had

established his preeminence at the ultimate dream factory and – almost

single-handed – defined, then reshaped the genre’s precepts and production

values we regard today as synonymous with those gala glamour days. Throughout

the 1930's and 40's, other studios tried to compete with Freed’s confections -

other producers on Metro’s back lot too. But for this brief wrinkle in time,

MGM musicals in general, and Freed’s in particular, were the envy of the

industry - lavishly appointed, untouchable money makers, much sought after by

movie lovers and readily to receive advanced A-list bookings at premiere movie

palaces like New York’s Radio City’s Music Hall. That Freed and the musical were

to suddenly – almost inexplicably – fall out of favor by the mid to late 50's

was as yet unknown and perhaps even more unanticipated. But in 1950, the year

Freed undertook to remake Jerome Kern/Oscar Hammerstein’s immortal stage

classic, Show Boat (released in 1951) he was undeniably at the top of

his game, and quite unaware that his Oscar-winning coup - An American in

Paris (1952) – the first musical to take home the Best Picture statuette

since 1936’s The Great Ziegfeld, was already on the horizon. As a matter

of record, Freed would top out the decade with an even greater victory, Gigi

(1958) – winning a ‘then’ record 9 Academy Awards, including a special

honorary Oscar for Maurice Chevalier.

Show Boat is one of those immortal Broadway shows that was an

immediate cultural touchstone in the American theater, and, long before its

silent movie debut in 1929, or its even more iconic 1936 movie made over at

Universal, costarring Allan Jones and Irene Dunne. It perhaps always irked Freed

that Universal, not readily known for its then musicals, had beat him for the

bragging rights to what eventually became one of their most popular and a

much-beloved screen adaptations. The ’36 version made beautiful music at the

box office, as well as aboard the Cotton Blossom. Freed in fact, attempted to

rectify this oversight with a considerable prologue dedicated to

Kern/Hammerstein’s masterpiece, in the opening of Till the Clouds Roll By

(1946), his self-indulgent and wholly fictionalized bio pic, reporting to be on

the life of Jerome Kern. This prologue featured Metro’s rising soprano, Kathryn

Grayson and pop fav, Tony Martin as Magnolia Hawks and Gaylord Ravenal

respectively, and, with the studio’s resident black chanteuse, Lena Horne

positively glowing in the role of the ill-fated mulatto, Julie Laverne. Alas,

casting Horne in an actual remake of Show Boat was a problem - virtually

the same one to have precluded Horne from appearing in anything except cameo

performances in other MGM musicals with the exception of Vincente Minnelli’s

superb, all-black Cabin in the Sky (1940). Freed’s resistance to Horne

owed its racial prejudice to the appeasement of the very much prevalent

anti-black sentiment in the South. Also, by 1950, Tony Martin was no longer the

crooning headliner he had briefly been in the late 40's. Curiously, Martin

would reemerge in popularity, costarring as leading man material opposite

Esther Williams in Easy to Love (1953). But opposite Grayson, who had

already been decided upon by Freed to reprise the role of Magnolia, Freed decided

he needed a richer baritone. So, the part ultimately went to rising talent,

Howard Keel instead.

There are those today who hold dear to the opinion

MGM’s remake of Show Boat is a wan ghost flower when set against Universal’s

outing. At least in retrospect, the 1951 re-envisioning does seem to ‘lack’

just a little something by way of that very distinct sparkle that permeated

virtually every frame of director, James Whale’s 1936 classic. The personality

of the piece is, if not wholly absent, then seemingly to have been replaced with

superior and undeniably more opulent production values. Indeed, Freed’s Show

Boat is a veritable feast for the eyes, sumptuously photographed by Charles

Rosher in 3-strip Technicolor. MGM’s resident arbitrator of good taste, Cedric

Gibbons oversees Jack Martin Smith’s spectacular production design, while

Walter Plunkett’s stunning costumes create a magnificent – and at times,

appropriately gaudy - screen spectacle in shimmering silks and satin. The studio edict under L.B. Mayer had been

two-fold: first – to make it big, do it well and give it class, and, second: a

standing order, that all men must be handsome/all women, beautiful. Perhaps

this is where the remake falters, in its basic lack of understanding Show

Boat is a story about common river folk trolling the Mississippi to put on

their lowbrow melodramatic skits and spirited buck n’ wings for the uncultured

masses. The MGM movie is therefore just a tad too glossy for its own good, its

cast – especially Grayson and Keel, but also Marge and Gower Champion - so

seasoned and pitch perfect, one begins to wonder why none have yet left the

river for the bright lights of Broadway and/or Europe. And Grayson, by 1951 was

a woman (only 31 years-young, perhaps) but ravishingly handsome and far too

mature to be convincing as the coquettish ingénue as written by Kern and

Hammerstein, who throws her heart after Keel’s no-account gambler, Gaylord

Ravenal.

Given the ousting of Mayer in 1950, and his

replacement, Dore Schary’s natural distaste for such ostentatious musicals, Show

Boat’s big screen remake, tricked out in all the finery Metro could muster

at its zenith, made it to the screen relatively intact. To be sure, the remake

makes revisions to the Kern/Hammerstein narrative, and, in fact, the tinkering

does improve the overall structure and timeline of the piece. In the original

stage play as well as the 1936 movie, Julie Laverne – passing for white – is

exiled from the show boat after it is discovered her mother was black. She is

never seen in the production again. Also, on stage, Magnolia and Gaylord become

estranged for a period of some twenty years, the show concluding with their

chance meeting, united in their love for an adult daughter, Kim. To rethink the

story, Freed brought in writer, John Lee Mahin, ironic, as Lee’s forte was not

musicals. However, Mahin is an exceptional constructionist who manages the coup

of tightening these narrative threads while retaining the play’s basic

structure, also condensing its sprawling timeline into a more manageable

‘movie’ length. Mahin also ensured Julie Laverne remains a presence, perhaps

even the catalyst for Gaylord and Magnolia’s reunion. The one unforgivable, but necessary change to

this version of Show Boat occurs at the outset of the story. The opening number

in the Kern/Hammerstein show – a product of its time and social climate,

further to harking back to another vintage entirely – included the lyrics, ‘niggers

all work on the Mississippi, niggers all work while the white folks play…’

For the 1936 adaptation, Whale changed ‘nigger’ to ‘darkie’, an

only slightly less offensive reference, and Freed had the lyric altered even

further for the prologue to Till The Clouds Roll By, to “…here we all

work on the Mississippi, here we all work while the white folks play…” By

1951, Freed could have run with this more racially tolerant alteration, but instead

elected to dump the lyrics entirely, the opener now an orchestral arrangement

by Conrad Salinger - a rather boisterous introduction to the Cotton Blossom as

it lazily sails through MGM’s moss-draped lagoon before pulling into its own

fictionalized version of Natchez.

Just as production on Show Boat was getting

underway, MGM’s corporate boardroom was rocked with an upset that, ostensibly,

no one saw coming. In 1932, Loew’s Incorporated President Nicholas Schenk, successor

to Marcus Loew, plotted to sell off Metro to rival studio mogul, William Fox. Loew,

a theater magnate, had placed his trust and Mayer and Irving G. Thalberg to

provide his ever-expanding chain of movie palaces with an endless succession of

product. This proved a symbiotic union until Loew’s untimely passing in 1927.

But Mayer’s successful thwarting of Schenk’s deal left a bitter acrimony

behind, one that Schenk never forgot and used to his advantage when, after Thalberg’s

death in 1936, Schenk pressured Mayer to reconsider hiring a replacement. Mayer

ignored this suggestion until late 1947, the year MGM reported a fiscal loss on

its ledgers for the first time. Schary, alas, was not beholding to Mayer. Nor

did he share in Mayer’s conservative view of popular entertainment. With Schary as his new V.P., the working

relationship between these two quickly soured. Schary’s forte – the ‘message

pictures’ clashed with Mayer’s enduring vision of MGM as the purveyors of old

time/big time, grand and glamorous entertainments. Schary also had no particular interest in

musicals even if, in 1950, they were still very much an integral part of the

studio’s bread and butter. When, after a particularly nasty stalemate, Mayer

confidently picked up his direct line to Loew’s New York office and presented

Schenk with his ultimatum, “me or Schary”, believing he would be backed,

Schenk instead seized the opportunity to unseat Mayer from his throne.

Henceforth, Schary would assume absolute control of MGM – a gross

miscalculation, with Schary’s tenure, tenuously balanced at best, and barely, to

last 7 years, until 1957’s horrendously costly debacle - Raintree County.

For a time, Schary’s installation as ‘boss’ at MGM did

little to impact the studio’s product, although infrequently he stuck his

fingers into pies, he had no business disturbing. In Show Boat’s case,

Schary promised close friend, Dinah Shore the part of Julie Laverne. When Freed

heard this, he promptly telephoned the star, explaining, “I’d love to do

something with you but you’re not a whore and that’s what the part is!” In the meantime, Freed turned his attentions

to casting William Warfield, whose rich baritone had made a sensation in a

classical recital in New York. Director,

George Sidney showed some concern over Warfield’s lack of movie experience. But

Warfield came to Show Boat after a series of stage successes in Call

Me Mister, Regina and Set My People Free. And in retrospect,

the part of Joe was hardly taxing from a dramatic standpoint. What had been an

integral role on the stage was now distilled in the movie to a mere cameo,

whose singular highlight undeniably remains ‘Ol’ Man River’ – the iconic

dirge, startling in its address of Black suffrage during this particular period

in American life. Freed’s initial plan was to shoot at least some of the

movie’s exteriors in Natchez and Vicksburg, finding a real show boat as

stand-in for the Cotton Blossom. But on the eve of Freed’s departure to the

South to scout locations, production designer, Jack Martin Smith had a

brainstorm and began to sketch out its details. Ultimately, and except for a

handful of establishing shots, Show Boat would be photographed on the

MGM back lot, with Tarzan Lake, redressed in false fronts and a newly constructed

dock. In hindsight, this was a stroke of genius that saved the production

millions.

Meanwhile, Sidney set off for the Deep South where he

became enamored with the idea of shooting ‘The Sprague’ – a genuine

riverboat from the 1800's. The Sprague had not seen active service in more than

forty-years. It had no engine to power it and needed to be dragged into the

middle of the Mississippi by a pair of tugs tactfully kept out of sight, with

pots lit aboard its decks to simulate acrid black smoke spewing from its

towering stacks. Unfortunately, the churning waters of the Mississippi caused

the tugs to slip and lose their tow lines, The Sprague caught in a drift

and rolling unexpectedly, its pots, tipping and catching fire. Back in

Hollywood, Smith arrived at a more credible and in fact, incredible solution to

counteract the dilemma of The Sprague. The MGM Cotton Blossom, 171 ft.

long and towering 57 ft. in the air, with three-tiers of deck and a 19 ½ ft.

paddle wheel, was by far one of the most impressive props the studio had ever

invested to build for a movie. As Tarzan Lake was only flooded to a depth of

roughly ten ft. the massive paddle-wheeler was arranged on a series of retarding

cables and touring winches, operated by 37 men, constantly in contact by radio

to successfully maneuver her into position. Inside, the ship was a veritable

marvel of studio craftsmanship, thoroughly unusable to shoot interiors, but

containing two oil burning asbestos boilers to pump smoke from its stacks.

There was also a working steam whistle, a calliope and a steam piston engine

built in to turn the paddle wheel.

With the backlot forest sufficiently trimmed in moss

and redressed with facades to suggest the South, the banks of Tarzan Lake laced

in a man-made humidity for added effect, the first sight of the Cotton Blossom

emerging slowly from around the bend was not only uncanny but drew immediate

applause from both cast and crew. Meanwhile, George Sidney and musical arranger,

Roger Edens were met with a force of nature of a different kind. Co-star, Ava

Gardner had agreed to play the part of Julie Laverne, but only if she could

sing her own songs. Both men reluctantly agreed before consulting with Arthur

Freed. Regrettably, it became almost immediately apparent the score was beyond

Gardner’s capabilities. Edens worked tirelessly to coax a performance from

Gardner while Sidney quietly went about casting a singer to dub in her vocals –

eventually hiring contract player, Annette Warren, as her octaves were closest

to Gardner’s speaking voice. Decades later Gardner’s original recordings of ‘Bill’

resurfaced. In realigning them to picture, while it remains quite obvious

Gardner’s voice is ‘untrained,’ her intonation of the lyrics rather excellently

captured the forlorn dramatic intensity of Julie Laverne with a husky,

whisky-drenched whisper, perfectly in keeping with the fictional character’s

spiraling alcoholism and dejected romantic sadness.

Show Boat opens with the arrival of Captain Andy Hawk’s (Joe E.

Brown) menagerie in a small Mississippi backwater. The Captain’s wife, Parthy

(Agnes Moorehead) is a stern manager, overseeing the troop while keeping a

watchful eye on her husband who has a penchant for drink and flirtations with girls.

The show boat’s arrival is greeted with excitement by the locals who race down

to the docks to catch a glimpse of the spectacle unfolding along the water’s

edge. However, when a fistfight between handsome leading man, Steven Baker

(Robert Sterling) and the boat’s engineer, Pete (Leif Erickson) breaks out

during Frank Schultz (Gower Champion) and Ellie Chipley’s (Marge Champion) buck

n’ wing, Capt. Andy dismisses Pete without question, putting into play a series

of events to destroy two lives. For Steve is very much in love with Julie

Laverne (Ava Gardner), the sultry dramatic star who, it is later discovered, is

from mixed parentage - miscegenation (a mixing of the races) illegal in the

state. Forced to choose, Steve takes Julie away, the pair, skulking off in the

middle of the night, leaving Capt. Andy’s show without a viable couple to

perform the pivotal dramatic skit in his travelling show.

Enter the utterly charming, Gaylord Ravenal (Howard

Keel) who offers up his services while flirting with the captain’s juvenile

daughter, Magnolia (Kathryn Grayson). Parthy is dead set against employing

Gaylord or allowing Magnolia to assume Julie’s dramatic role as it includes the

sensation of an on-stage kiss between its two principles. Capt. Andy quells Parthy’s

concerns by altering the scene so the kiss will be administered cordially on

the hand rather than on the lips. However, as the show boat steams on through

its series of engagements, the sketch featuring Gaylord and Magnolia becomes

its centerpiece, Gaylord frequently inserts chaste kisses on the cheek, before

securing a delay in Parthy’s arrival to the theater one night, and thus using

the opportunity to ravage Magnolia rather intensely on the lips. The crowd

loves it, and indeed, so does Magnolia who begins a romance with Gaylord under

Capt. Andy’s watchful eye. When Parthy discovers the lover’s embraced on the

Cotton Blossom’s moonlit deck after hours, she orders Gaylord off for good. In

reply, Gaylord proposes to Magnolia who accepts him and the couple leaves the

show boat together.

Gaylord’s past profession is as a gambler. Now, he

reverts to his old ways, winning enough to spend quite lavishly and furnish his

new bride with a very good time. This tide of luck, however, is extremely

fickle and not to last. The streak seemingly broken for good, the couple pares

down their lifestyle. Magnolia, encourages Gaylord to remain true to himself.

She stands beside him, even as he falters and lands them both into extreme

debt. Ashamed of the financial ruin brought upon them both, Gaylord elects to

abandon Magnolia in Chicago. There, a tearful Magnolia is discovered by Ellie

and Frank who are in town to entertain at the Trocadero. Recognizing how badly

Magnolia needs a job, Frank and Ellie take her with them to the open auditions.

The Trocadero’s stage manager (Chick Chandler) is having a rough time keeping

his star attraction, Julie Laverne sober. Indeed, Julie’s bittersweet rendition

of ‘Bill’ brings down the house. But when she spies Magnolia from the

wings, Julie nobly withdraws, allowing Magnolia to replace her. On New Year’s

Eve, Magnolia suffers an acute attack of stage fright. The inebriated crowds are

unkind. But Magnolia’s confidence is bolstered by the sight of her tipsy father

who has come to the Trocadero with a gaggle of friends to ring in the New Year,

quite unaware his daughter is part of their floor show. Afterward, Magnolia confides

in her father, she is with child – her secret never revealed to Gaylord for

fear it would have upset him.

Returning to the Cotton Blossom, Magnolia gives birth

to Kim (Sheila Clark). From here, director George Sidney’s narrative devolves

into a montage spanning five-years in a matter of moments. Kim, now a little

girl, and Gaylord, slowly to reclaim his fortunes as a gambler, aboard various

floating river palaces. A chance meeting with Julie – who has hit the skids and

is being abused by her latest lover – alerts Gaylord to the fact he has a

daughter. The news is humbling and Gaylord makes his journey back to the Cotton

Blossom where he discovers young Kim playing with her dolls on the docks. Moved

to engage the child in polite conversation without divulging his paternity to

her, Gaylord learns Kim has been named ‘geographically’ – for being born

somewhere in the middle of Kentucky, Illinois and Missouri. From the Cotton

Blossom’s balcony, Magnolia spies ‘father and daughter’ together and makes her

presence known to Gaylord. Given the circumstances of their separation, she

harbors no ill will, and, in fact, reveals how much she still is in love with

him. On board the Cotton Blossom, Capt. Andy looks on approvingly,

miraculously, Parthy too – who playfully chides her husband for his

predilection for strong drink before encouraging him to cast off for their next

port. As Gaylord and Magnolia embrace on the decks of the Cotton Blossom –

presumably to resume their relationship – a darkened figure emerges from the

shadows on the docks; Julie – aged well beyond her years, with tears of

satisfaction majestically caught in the glint of evening sunset as the Cotton

Blossom pulls away from port, tragically, with no happy ending in store for

her.

Show Boat is precisely the sort of musical extravaganza MGM could

mass market to the public as the epitome of chic good taste during its heyday.

It teems with pageantry, spectacle and that ultra-sheen of spellbinding

perfectionism for which Mayer’s fantastic empire remains justly famous. Such

lavish flamboyance does not really suit the grittier aspects of Show Boat’s

sordid tale. Indeed, and visually, the movie tends to look just a tad

over-inflated at times. Marge and Gower Champion are much too sophisticated for

the riverboat circuit, their dancing - peerless, their dramatic performances,

echoing more social affluence than anything else. William Warfield’s rendition of Ol’ Man

River rattles the timber. And yet, in retrospect, it remains a recital by a

professional singer rather than the epitome of a spontaneous outburst of sweat-born

frustration with one’s lot in life. Even so, Warfield’s Ol’ Man River

remains the centerpiece of this Show Boat’s musical repertoire and

deserving of high praise. Ditto for Ava Gardner’s ‘Bill’ – her ‘acting’

of the song, beautifully wed to Annette Warren’s vocals, creating a tragic tome

to positively tear the heart out. What remains rather off-putting is the

coupling of Kathryn Grayson and Howard Keel – each, in very fine voice, but

rendering their highlighted duet, ‘Make Believe’ a stilted, theatrical

waxworks. The Champions are in very fine form, singing and dancing ‘I Might

Fall Back on You’ with an exuberance that really transforms this moment

into nothing less than a show-stopper.

There is nothing to touch Jack Martin Smith’s

impeccable production design, always gorgeous and occasionally even in keeping

with the true intent of the material. Mid-way through production, George Sidney

became ill, necessitating Roger Edens taking over the directorial duties.

Edens, who had never directed before, seems to instinctively know where the

camera belongs, retaining Sidney’s visual continuity. It is virtually impossible

to deduce which sequences in the film were not directed by Sidney – or rather,

directed by Edens and/or vice versa. Without a doubt, Show Boat is an

MGM musical in the very best tradition of that distinct – now defunct –

classical strain of studio-bound style. The sets, while obvious in their ‘set-like’

quality, are nevertheless authentic and stunningly handsome in glorious

Technicolor. Ditto for Walter Plunkett’s costumes, a veritable potpourri of

fabrics, colors and patterns cleverly integrated to give the illusion of

authenticity. In January 1951, principal

photography on Show Boat wrapped. However, Arthur Freed was less than

enthusiastic with the results, believing its 3rd act dragged. Roger Edens came

to a decision – Magnolia and Gaylord’s troubled romance took too much time to

evolve. Hence, in the editing process, these scenes were intensely recut with

Edens aggressively hacking out whole portions of dialogue, distilling

everything down to dramatic action only and, in some cases, montage to give the

story a new momentum.

Ava Gardner’s original vocals were allowed to stay in

for the first studio preview at the Bay Theater. But by the time Show Boat

had its national release, Annette Warren’s vocals had been laid over Gardner’s,

much to the actress’ dismay. When Show Boat debuted, it was an immediate

sensation with audiences who almost universally filled out their prevue cards

with glowing/gushing praise. The movie went on to gross $8,650,000.00 on its

$2,295,429.00 budget -- a qualified hit by any measurement. However, when it

was decided to release a soundtrack album, only Gardner’s tracks – not Warren’s

– were included. In the infancy of cast

recordings virtually none of the plushily padded underscore – not even the

bombastic main title – made it. Viewed today, Show Boat is an

exceptionally well-orchestrated entertainment, its sophistication and vivacity beyond

reproach. Yet, oddly enough the movie does not retain its status as one of

MGM’s finest musical offerings. When

lists are compiled of Metro’s truest classics, the A-list titles are always the

same, beginning with The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Meet Me In St. Louis

(1944) and ending with An American in Paris (1950), Singin’ In the

Rain (1952), The Band Wagon (1953), and, Gigi (1958). With so

much entrancing entertainment on tap, it is perhaps forgivable Show Boat

somehow never makes this cut. To be sure, and furthermore to be clear, MGM’s

list of exceptional accomplishments in the musical genre hardly ends with these

noted few examples. And certainly, no claim is made to the contrary. But at

least in retrospect, Show Boat settles into that very solid, and much

broader second-tier of sterling silver-age product, arguably, as beloved, if

decidedly never to be mentioned in hushed reverence as in the same league with

the aforementioned.

The Warner Archive (WAC) has been overdue with this

Blu-ray release of Show Boat. Almost a decade ago, then VP in Charge of the

studio’s formidable asset management, George Feltenstein, hinted that a deluxe

version of Show Boat, vaguely reminiscent of the box set released to

LaserDisc back in 1989, would soon hit shelves, containing all 3 versions of

the celebrated musical. Regrettably, and rather inexplicably, this was never to

occur. Hence, when Criterion released the 36’ James Whale version as a solo

offering, via their distribution agreement with Warner Bros. at the outset of 2020,

the concern from fans was that the 51’ remake would not be coming down the pike

any time soon. Mercifully, this too proved to have its misdirection. After

enduring 2 decades worth of endlessly reissues of the brutally tired old DVD whose

master, WAC’s new-to-Blu and ground-up restoration of Show Boat can

safely be declared a genuine cause to stand up and cheer. WAC has again

illustrated its proficiency for restoring and remastering some of MGM’s

greatest 3-strip Technicolor musicals in hi-def. I suspect the clean-up on Show

Boat was not only extensive, but expensive, as, not only have virtually all

age-related blemishes been eradicated, but the studio has spent wisely to realign

the original negatives to ensure an optimal presentation.

Prepare to be dazzled, as this Technicolor production

sparkles with some of the most stunningly handsome 3-strip Technicolor

photography known to man. The image is crisp throughout, revealing a startling

amount of richly saturated clarity, exquisite contrast, and, light smattering

of film grain looking extremely indigenous to its source. On television

monitors, the image is gorgeous. In projection, it gives the uncanny illusion

of viewing a 35mm original negative, immaculately curated for our viewing

pleasure. So, kudos are in order here. Thank you, WAC. A million times and

again – thank you!!! WAC has done away with the fraudulent 5.1 Dolby Digital

that accompanied the old DVD release. This basically re-channeled the mono audio,

creating some truly weird echoes and reverb. Instead, we get a restored and

remastered 2.0 DTS, indicative of the original presentation which, after all,

was presented in theaters in 1950 in mono. Ported over from the old MGM/UA LaserDisc

box set, but absent from the DVD release, is director, George Sidney’s audio

commentary. Encouragingly, this disc also includes the Show Boat prologue

from Till The Clouds Roll By (one can only hope this to be a

foreshadowing that the complete movie is already in the queue for its own Blu

release sometime soon), plus, Ava Garner’s outtakes for ‘Can’t Help Lovin’

Dat Man’ and ‘Bill’. We also get the 1952 Lux Radio adaptation and

original theatrical trailer, in HD. Bottom line: Freed’s Show Boat is a

masterpiece. While it remains debatable which of the two sound versions best

captures the essence of the Kern/Hammerstein stagecraft, what is irrefutable

herein is that the utmost care has been taken by WAC to ensure both editions

are available to the public in optimal quality to judge the results for

themselves. Show Boat’s a’comin’! You better believe it.

FILM RATING (out of 5 – 5 being the best)

4

VIDEO/AUDIO

5+

EXTRAS

3.5

Comments